Yesterday (April 24, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest - Consumer…

Bank of England finally catches on – mainstream monetary theory is erroneous

The Bank of England released a new working paper on Friday (May 29, 2015) – Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds – – facts, theory and evidence (updated June 2019) – which further brings the Bank’s public research evidence base into line with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and, thus, further distances itself from the myths that are taught by mainstream economists in university courses on money and banking. The paper tells us that the information that students glean from monetary economics courses with respect to the operations of banks and their role in the economy is not knowledge at all but fantasy. They emphatically state that the real world doesn’t operate in the way the textbooks construe it to operate and, that as a consequence, economists have been ill-prepared to make meaningful contributions to the debates about macroeconomic policy.

Here are the two substantive conclusions of the BoE first so you know where we are heading. The authors conclude that:

1. “The currently dominant intermediation of loanable funds (ILF) model views banks as barter institutions that intermediate deposits of pre-existing real loanable funds between depositors and borrowers. The problem with this view is that, in the real world, there are no pre-existing loanable funds, and ILF-type institutions do not exist.”

In other words, the mainstream economic models that pervade textbooks and teaching programs in economics are fantasy – they analyse institutions that “do not exist”.

2. “in the real world, there is no deposit multiplier mechanism that imposes quantitative constraints on banks’ ability to create money in this fashion. The main constraint is banks’ expectations concerning their profitability and solvency.”

If you read any macroeconomic textbook written for mainstream (neo-liberal) courses you will find some account of the money (deposit) multiplier as it applies to ‘reserve-constrained’ commercial banks.

But as the Bank of England now reliably informs the world, this sort of model is not “in the real world”. Banks are not reserve-constrained.

The only surprising thing about the paper is that it took so long for a major financial institution like the Bank of England to come clean and tell the world that the textbook theories that students rote learn are of no relevance to the real world we live in.

The US Federal Reserve Bank of New York, acknowledged the failings of mainstream monetary theory in the September 2008 edition of their Economic Policy Review – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy.

That article demonstrated why the account of monetary policy in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks from which the overwhelming majority of economics students get their understandings about how the monetary system operates is totally flawed.

I don’t recommend reading the BoE paper in full. It is a fairly arid technical exercise that attempts to salvage so-called dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models used by the central bank with more realistic understanding of the way banks operate in the real world.

Only read it if you are good at mathematics and want to waste 30 minutes of your life.

The DSGE framework is intrinsically flawed and should be scrapped altogether. There are now many attempts to resurrect the standard DSGE model, which failed dramatically to predict the crisis.

These attempts, in one way or another, add ‘financial frictions’ or other variations to the standard DSGE models.

Please read my blog from 2009 – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on DSGE modelling and New Keynesian economics.

The BoE paper is another one of these attempts, albeit it does recognise that the failings of the previous mainstream models was rather catastrophic and required major rather than minor surgery to remedy. The problem is that the patient died a long time ago and the BoE is just operating on a corpse.

The BoE paper recognises that when the GFC struck:

Macroeconomic theory was however initially not ready to provide much support in studying the interactions between banks and the real economy, as banks were not a part of most macroeconomic models.

Which is not exactly correct.

They should have said ‘mainstream macroeconomic theory’ because Post-Keynesian economists and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) theorists (the latter being a subset of the former in this context) certainly incorporated sophisticated understandings of how banks worked into their core macroeconomic models and had known about the financial vulnerability that was increasing in the lead up to the crisis.

The BoE paper note that after the crisis the mainstream literature has suddenly “started to pay attention to the role of banks and prudential banking legislation” but the dominant new intiatives remain flawed:

… due to the fact that this literature is almost without exception based on a version of the intermediation of loanable funds (ILF) model of banking.

The problem is that the core of the mainstream approach is wrong – at the elemental level and economist refuse to give up these notions because if they did the whole edifice of macroeconomic theory they preach would fall to the ground. The whole shebang is flawed and of no use for those keen to understand how the monetary system operates.

So instead of acknowledging that their fundamental approach is wrong, mainstream economists have adopted so-called ad hoc responses to anomaly to defend their flawed theory.

In his great 1972 book – Theories of poverty and underemployment, Lexington, Mass: Heath, Lexington Books), David M. Gordon wrote about this mainstream behaviour. His context was mainstream human capital theory, which at the time had been exposed as being deeply empirically deficient.

David Gordon said that mainstream economists continually responded to empirical anomalies with these ad hoc or palliative responses.

So whenever the mainstream paradigm is confronted with empirical evidence that appears to refute its basic predictions it creates an exception by way of response to the anomaly and continues on as if nothing had happened.

Please read my blog – In a few minutes you do not learn much – for more discussion on this point.

The BoE paper outlines the basic mainstream model of banking – the “intermediation of loanable funds (ILF) model” – which is says:

… bank loans represent the intermediation of real savings, or loanable funds, from non-bank savers to non-bank borrowers. Lending starts with banks collecting deposits of real savings from one agent, and ends with the lending of those savings to another agent.

But in “the real world, the key function of banks is the provision of financing, or the creation of new monetary purchasing power through loans, for a single agent that is both borrower and depositor.”

MMT has for two decades been writing that loans create deposits and are not reserve constrained. The BoE paper says that in doing so:

The bank therefore creates its own funding, deposits, in the act of lending. And because both entries are in the name of customer X, there is no intermediation whatsoever at the moment when a new loan is made. No real resources need to be diverted from other uses, by other agents, in order to be able to lend to customer X.

So in one paragraph we learn that:

1. That scarce savings are not on-lent by banks, which means that the mainstream theories about crowding out are erroneous.

2. Banks do not operate to attract savings from depositors and then on-lend them.

But there is more. I have often written in the past – building on the work of Michal Kalecki and others – that investment brings forth its own saving.

Please read my blog – Why budget deficits drive private profit – for more discussion on this point.

This was in direct refutation of the mainstream view that savings were lodged in banks as a prior source of funding for investment and competition for those savings (say from government deficits) would drive up interest rates and crowd out private investment.

It is one of the mantras of mainstream theory and drives the relentless attacks on fiscal deficits by conservatives. It hasn’t an ounce of truth to it.

To fix ideas, this is what the mainstream model tells students. The flawed Loanable Funds doctrine is derived from the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times.

If consumption spending fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

This is the reasoning that leads mainstream economists to eulogise about the ‘efficiency’ of the free market and warn us against the dangers of government intervention which inhibits this ‘efficiency’.

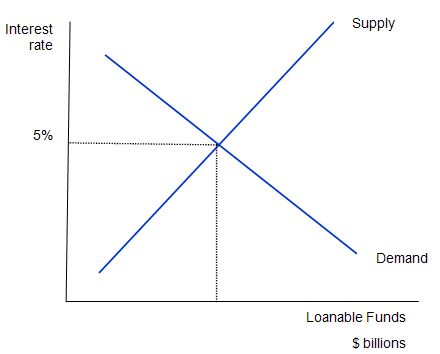

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

One of the most popular macroeconomics textbooks by Greg Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

I provide a refutation of the theory of loanable funds in this blog – Budget deficits do not cause higher interest rates – for more discussion on this point.

Its conception of the way the banking operates is deeply flawed. There is no finite pool of saving that is competed for. Loans create deposits so any credit-worthy customer can typically get funds. Reserves to support these loans are added later – that is, loans are never constrained in an aggregate sense by a “lack of reserves”. The funds to buy government bonds come from government spending! There is just an exchange of bank reserves for bonds – no net change in financial assets involved. Saving grows with income.

In addition, please read the following blogs – Money multiplier and other myths – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

But importantly, deficit spending generates income growth which generates higher saving. It is this way that MMT shows that deficit spending supports or ‘finances’ private saving not the other way around.

The mainstream approach was to see interest rates as adjusting to equilibrate (real) saving and investment and thus ensure that aggregate demand would always be equal to aggregate supply – thus negating the possibility that the economy could suffer from a shortage of demand.

This denial of unemployment was the basis of Say’s Law (later Walras’ Law).

However, Keynes and Kalecki clearly understood that saving and investment were brought into equilibrium (in a closed economy without a government sector) by variations in national income driven by changes in effective (aggregate) demand.

That insight provided the fundamental break with classical thinking that dominated economics (and policy) at the onset of the Great Depression and which, when applied, worsened the depression.

This is also the basic idea that drives the spending multiplier model. Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point. Thus increased investment spending stimulates aggregate demand and firms respond by increasing production.

This, in turn, leads to higher wage and salary payments and higher induced consumption which feeds back into the spending stream and promotes further output and income. At each stage of the process, some of the income generated goes to saving and so the successive consumption spending flows become smaller and smaller until they exhaust. At that point, the sum of the saving generated by the income responses will equal the initial investment injection and the economy regains equilibrium.

A person thinking from a micro perspective might think that if people spend more now (that is save less) they will have less funds at the end of the period. It is here that the fallacy of composition enters the fray.

To illustrate, Kalecki asked “what would be the sources of financing this investment if capitalists do not simultaneously reduce their consumption and release some spending power for investment activity?”

He responded as such (in his 1966 book – Studies in the Theory of the Business Cycle (Blackwell, Oxford), page 46):

It may sound paradoxical, but according to the above, investment is ‘financed by itself’.

So, while that might be true that an individual business firm or person, acting in isolation will have less funds if it (they) spends more now, it cannot be true for the economy as a whole.

Why? Answer: the consumption of one capitalist are the source of profits for another capitalist. Spending by a consumer is another consumer’s income. So investment brings forth its own saving!

Kalecki clearly understood that counter-intuitive notion that investment “automatically furnishes the savings required to finance it” as long as there is idle capacity. That is, as long as increasing aggregate demand does not outstrip the real capacity of the economy to produce.

This has all been known for decades and the BoE has taken a while to catch on.

But the BoE paper is now emphatic:

Furthermore, if the loan is for physical investment purposes, this new lending and money is what triggers investment and therefore, by the national accounts identity of saving and investment (for closed economies), saving. Saving is therefore a consequence, not a cause, of such lending. Saving does not finance investment, financing does. To argue otherwise confuses the respective macroeconomic roles of resources (saving) and debt-based money (financing).

Therefore, there can be no crowding out of private spending by public deficits through interest rate channels.

The BoE paper correctly notes that:

… banks technically face no limits to increasing the stocks of loans and deposits instantaneously and discontinuously does not, of course, mean that they do not face other limits to doing so. But the most important limit, especially during the boom periods of financial cycles when all banks simultaneously decide to lend more, is their own assessment of the implications of new lending for their profitability and solvency.

Please read my blog – Lending is capital – not reserve-constrained – for more discussion on this point.

Banks lend if they can make a margin given risk considerations. That is the real world. If they are not lending it doesn’t mean they do not have ‘enough money’ (deposits). It means that there are not enough credit-worthy customers lining up for loans.

Banks lend by creating deposits and then adjust their reserve positions later to deal with their responsibilities within the payments system, knowing always that the central bank will supply reserves to them collectively in the event of a system-wide shortage.

The BoE paper links that reality to a conclusion that the money multiplier theory, which is central to mainstream textbook expositions of the monetary system, is inapplicable.

We read that:

The deposit multiplier (DM) model of banking suggests that the availability of central bank high-powered money (reserves or cash) imposes another limit to rapid changes in the size of bank balance sheets. In the deposit multiplier model, the creation of additional broad monetary aggregates requires a prior injection of high-powered money, because private banks can only create such aggregates by repeated re-lending of the initial injection. This view is fundamentally mistaken. First, it ignores the fact that central bank reserves cannot be lent to non-banks (and that cash is never lent directly but only withdrawn against deposits that have first been created through lending). Second, and more importantly, it does not recognise that modern central banks target interest rates, and are committed to supplying as many reserves (and cash) as banks demand at that rate, in order to safeguard financial stability. The quantity of reserves is therefore a consequence, not a cause, of lending and money creation.

Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

This reinforces the MMT understanding that loans are made independent of their reserve positions. Depending on the way the central bank accounts for commercial bank reserves, the latter will then seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period.

They can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these transactions will not add the required reserves. In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow outright through the device called the ‘discount window’. There is typically a penalty for using this source of funds.

At the individual bank level, certainly the ‘price of reserves’ will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window is sufficient, the bank will lend.

So the idea that reserve balances are required initially to ‘finance’ bank balance sheet expansion via rising excess reserves is inapplicable. A bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements. The bank expands its balance sheet by lending. Loans create deposits which are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit) which creates new bank liabilities is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank.

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion which leaves a bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan as a consequence of the ‘penalty’ rate the central bank might exact through the discount window. But it will never impede the bank’s capacity to effect the loan in the first place.

In other words, the stock of reserves at any point in time is a reflection of bank lending activity rather than cause.

Which means that one of the basic premises of Monetarism – that the central bank can control the money supply is false.

Conclusion

The BoE paper is one of many emerging from central banks in the wake of the GFC which seek to resituate the institutions in the economic literature.

They are now openly critical of the mainstream approach to banks and the monetary system that dominates the mainstream academic literature.

So while a few years ago, MMT was vilified by US macroeconomics academic Mark Thoma who said “”I think it’s just nuts” (Source), the large central banks are now letting Dr Thoma and his mainstream ilk know just what they think of his viewpoint.

Thoma and Mankiw, both academic commentators with prominent public profiles represent what is wrong with economics. They teach and prosletyse theories that are not applicable to the real world we live in.

Whether they are applicable somewhere else is moot!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I agree with Bill when he says “I don’t recommend reading the BoE paper in full.” Kumhof actually has form here. A couple of years ago he and Jaromir Benes wrote a similar paper which was into DGSE as well. They tried to reconcile full reserve banking with DGSE and as part of that effort claimed it was impossible impliment full reserve without a massive debt jubilee: bizarre. See:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=26178.0

Still, lots of academic economists keep themselves employed that way: turning out what Bill rightly calls “arid technical exercises”. But Kumhof produces plenty of less arid and more readable, common sense material as well.

Next, that Kumhof paper to which Bill refers is not actually official BoE policy. It says in the small print that “Any views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and so cannot be taken to represent those of the Bank of England…”. In contrast, the BoE published a short and very readable article last year written by actual BoE staff and with a similar message the Kumhof paper. And I assume that THAT IS official BoE thinking. See:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

Next, while I fully agree that loans create deposits, I don’t think it’s correct to totally reject the idea that banks intermediate between depositors and borrowers. Nor is it correct to say there are no “pre-existing loanable funds”. I suggest THERE ARE pre-existing loanable funds: the deposits created in the past – 5, 10 and 20 years ago.

To illustrate, if an economy is at capacity, and the commercial bank system spots new viable borrowers, it can try to lend out money created from thin air (i.e. do the “loans creates deposits” trick). But that will boost demand, which will induce the central bank to raise interest rates so as to curb inflation. So in that scenario, the loanable funds idea has some validity.

Dear Bill

In a closed economy, (S – I) + (T – G) = 0. Let’s start with a situation in which S = I = 100, and in which T = G = 100. Now, T is dropped to 70 while G is increased to 120, so T – G = -50. As a result, S – I must now be 50. This could mean that S is now 130 and I is 80. In other words, I goes down by 20. Is this not what many mean by crowding-out, namely that big government deficits can reduce investment because savings, instead of being used to finance investment, are used to finance government expenditure?

Regards. James

Bill,

With absolutely nothing available to counter the mainstream narrative, undergraduates predictably end up as zombies. Frankly, it’s a miracle that there’s as much resistance as there is by students.

Mark my words, your soon to be released textbook will be the end of Mankiw and the rest of them. New Keynesian and New Classical professors alike will find themselves waking at ungodly hours in cold sweats screaming “Mitchell! Mitcheeeeeellllll!!!”

Any update on the release date? By which publisher and an approximate cost?

James, I think this comment at MNE is relevant to your query …

Dear James (at 2015/06/01 at 15:00)

Your numerical example establishes nothing of interest. Sorry.

First, what model did you develop to generate the initial equilibrium where S = I = 100 and T = G = 100?

What is the Marginal Propensity to Consume, the Tax Rate (or is it a lump sum tax)?

What is the equilibrium consumption level?

Second, why does Investment have to drop? It could easily be the case that S goes to 150 while Investment remains unchanged at 100. Further, in any simple closed economy model, with a deficit rising by 50, consumption will rise significantly as a result of the expenditure multiplier and investment will rise because of the accelerator effect.

A simple model that could give your results would have the following parameters:

MPC = 0.9131

T = lump sum 100 irrespective of income level.

Initial equilibrium income will be 1255 if I and G (exogenous) are 100 under these conditions. Saving will be 100 given it is Y – T – C, which means C = 1055.

Okay, that is a starting point that generates your initial equilibrium with the standard behavioural assumptions built in (MPC, MPS and T rate).

Now we shock that little model by increasing G to 120 and dropping the lump-sum tax to 70.

The new equilibrium has the following outcome:

National Income = 1381

Consumption = 1161

Investment = 100

Government spending = 120

Saving = 150

Taxes = 70

That gives (S – I ) = (G – T) = (150 – 100) = (120 – 70) which is the equilibrium sectoral balances in this model.

So with the starting equilibrium parameters, Saving rise to 150 because national income has risen on the back of the stimulus from the deficit.

There was no financing of the Government deficit required. Indeed, the deficit funded the extra private saving via its positive effect on national income.

If I had have added an accelerator effect to the Investment function in this simple model (so I = aY) then Investment would have risen a bit in this model and pushed savings out even further for a given deficit increase.

Try writing out and solving a simple closed economy model that gives your results. You will not be able to so don’t spend the time.

best wishes

bill

Dear jrbarch and Bill

I’m aware that an accounting identity is not an economic model and is silent on causation. I didn’t say that investment had to fall, only that such a fall is compatible with the equation. I was wondering whether such a fall in investment was at all possible. We should also bear in mind that G is not necessarily consumption. The rise in G could mean an increase in public investment, to the detriment of private investment.

Regards. James

Uh oh! Apologies Bill and James. What I thought was just an identity~equation issue is actually way out of my depth. Thought I was being helpful but should have known better …..

“The rise in G could mean an increase in public investment, to the detriment of private investment.”

What makes you think you can’t do both? That’s a crowding out argument for which there is no evidence.

There is little difference between investment and consumption. They both consume the products of current output which tends to expand to meet the demand.

And one person’s consumption (training courses for example) is another person’s investment.

The idea that consumption is ‘bad’ and investment is ‘good’ comes from the same school of myths as public spending is ‘bad’ and private spending is ‘good’ (and probably four legs ‘good’, two legs ‘bad’).

Without consumption there is no reason to investment. Dynamically there needs to be enough of each to justify the other up to the technical capacity of the economy. That relationship is simply not representably by a static equation.

nice to see a little reality intruding into more economic thinking.

As for the debate above how do accounting identities represent any kind of equilibrium?

I think the biggest jolt of reality economics and the social sciences in general need

is to understand it is all just us ,human beings rubbing along there are no equilibria.

There are no automatic mechanisms (price ones or others) which optimize resource

development and distribution just primates ,animals interacting .

Modern science reveals the reality they are interacting in is incredibly complex and interrelated

and fundamentally chaotic.

Dear James,

S could also be 170 and I could be 120. It’s more likely to be this than 130/80 because of the stimulatory effect of the budget deficit, although this would depend on where total spending is in relation to productive capacity. If total spending previously equalled productive capacity, then I (investment) would fall if there was no increase in productive capacity over the intervening period. If so, that’s not crowding out in the traditional sense – that’s a society choosing to have the government provide a greater percentage of total ouput.

Here’s an error made by a lot of people, including most economists. You seem to have made this yourself with your last question. S = I = 100 does not strictly mean that there has been savings of 100 in the form of net financial assets and that this has been used by firms for investment purposes (i.e., I of 100).

Investment is a form of savings. I is S! In a 2-sector model (2SM) where there is no central government to inject net finanical assets through deficit spending, investment in the form of producing capital goods to generate tomorrow’s income is the only way to net save. This is why S must equal I in a 2SM. Investment is financed out of current income, which is why I believe investment is not strictly an injection of spending power. In a 2SM, investment is simply a diversion of spending away from consumer goods to capital goods.

In a 3SM, there is now a second means of net saving. It is now possible to net save in the form of net financial assets, although it is necessary for the central govt to deficit spend to accommodate it.

Hence, in a 3SM, if S = 150 and I = 100 (S > I), there is 100 of savings in the form of capital goods and 50 of savings in the form of net financial assets. Because it is now possible to borrow, you can have the situation where S < I. So if S = 50 and I = 100, there is still 100 of savings in the form of capital goods. But there will be -50 savings (dissavings) in the form of net financial assets (net liabilities).

In a 4SM, a further savings possibility opens up. It is now possible to net-export and accumuluate net financial assets denominated in foreign currencies. This is an undesirable way for the private sector of a nation to source its net savings because it involves a nation giving up more useful stuff to the ROW than it gets in return. It is also uncecessary if a nation has a central govt willing to deficit spend to the level needed to ensure full employment, since the income level will be sufficient to enable the private sector to meet its spending and net savings desires. It also means the central govt can acquire the real resources that would have been handed to the ROW (X – M) which they can use to build more schools, hospitals, and universities.

Although I + G + X = S + T + M, I think it is misleading to class I and X as injections. I believe there is only one form of financial injection into an economy. It exists as the injection provided by the deficit spending of a central govt – either the domestic govt (G – T) or a foreign govt (X – M).

Assuming a 3SM, one also has to be careful how they view changes in T and S. If the private sector is hell-bent on positively net-saving (i.e., S – I = 50), which means it is willing to adjust its discretionary spending to ensure its net savings remain at 50, then G will determine T and the central govt can't possibly run anything but a deficit of 50 (aka Australia of late). If the central govt tries to run a budget surplus of 50 (G – T = – 50) and the private sector is hell-bent on maintaining its spending desires, then the private sector must dissave (S – I = -50). This is what happened in the 1995-2007 period. It caused the private sector to accumulate unsustainable debt levels. It was the main cause of the GFC.

Cheers, Phil

“…. it doesn’t mean they do not have ‘enough money’ (deposits). It means that there are not enough credit-worthy customers lining up for loans.”

Added to which, since the GFC the banks have been very much restricted in whom they can lend to because of stringent government guidelines. For example, in the UK tenants typically pay £550 a month (outside London) to rent a flat. But they can’t get a loan to buy a flat that would have a monthly repayment of £500 because their income does not meet the multiplier. Hence most new buildings are snapped up by landlords to rent out. Worse, small businesses can’t get loans to expand.

There really are rainy days.Stuff needs fixing, replacing.Human stuff too.

Our personal ability to get our hands on money tokens tends to deteriorate

towards the end of life .Households need monetary savings .As ever a private

sector focused on short term massive acquisition of money tokens for a few

is fundamentally inadequate as many recipients of private pensions can testify.

Whatever the accounting identities the reality is the majority do not have enough

savings.Monetary sovereign governments are letting down their citizens .

Dear Phil

I agree with your comments. Let me just clarify that I’m not an economist. I have never been to a university, and whatever economics I know I have acquired by reading.

Dear Neil

I agree with you that investment is not intrinsically good. Just as exports are only a means to obtain imports, so investment is only a means to maintain or increase the level consumption. The higher the ratio of imports to exports is, the more advantageous it is for a country. Similarly, the higher the long-term ratio of consumption to investment is, the better it is for a population.

Let’s take 2 grain farmers. Both have the same area and quality of land and both produce the same amount of grain. However, one does it with 500,000 dollars worth of machinery and the other with machinery worth 900,000. Obviously, the first one is doing something right while the second one has invested inefficiently.

Regards. James

@ Ralph

I’m not sure if the even the quarterly BoE bulletins are exempt from the “views expressed are…”

I think the BoE is super keen not rock any boats regarding policy that *could* be regarded as ‘controversial’. Especially with respect to potential influence on rate setting and financial regulation. And whole concept of Forward Guidance is essentially one of “views expressed..” rather than actions, hence the very strict control over what is the ‘official’ line.

I’ve had long discussion with a bank accountant over ILF/FMC, initially he was loanable funds indoctrinated (viewing as he does from the perspective of an isolated institution) now I believe is a little more open. However he still points out to me that generally the balance of loans and deposits *is* closely matched (by design).

Of course the key issue is when all banks start doing the same pro-cyclical thing because most of the time they are basing their action on what other banks are doing.

Congatulations to the hard working Modern Monetary Theorists, without whom this much reckoning by a central bank probably would have still been decades away. It will be interesting to watch what happens next!

“Obviously, the first one is doing something right while the second one has invested inefficiently.”

Has he, or has he just been at the game longer and spent more?

It’s not that simple.

Bill,

These interventions are indeed useful but the guy who wrote this paper has an extremely shallow understanding of monetary economics. Many of us have encountered him before at presentations and he is far more interested in building DSGE models with ‘novelty features’ than he is in seriously discussing monetary macroeconomics. Like most mainstream modelers who figure out that money is endogenous his ‘solution’ is top advocate the old Chicago Plan from the 1930s.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

Of course, no one who actually understands the endogenous/exogenous money debates would advocate this absurd proposal (which would have zero effect on banks’ ability to create money).

Beware those who come bearing poisoned fruit. And most especially beware math nerds in search of novelty who end up talking absolute nonsense. I think we’re best off choosing our allies carefully here.

When credit creation by banks becomes an economic bubble as it has today with housing mortgages here in the UK being approximately 7-10 times income, what should governments do to bring this level in line with what the economy is able to pay?

Can this be contained by full employment strategies through deficit spending, or overt monetary finance, or has the debt grown so large that some other strategy would be needed. The reason that I ask is that Michael Hudson and Steve Keen have suggested debt write offs or the creation of sovereign currency to give to people to pay down their debt.

As this would destroy money by clearing bank loans, it would not create inflation, but it would free up money that people already have for spending, which would stimulate the economy. It is a little like bailing out the people instead of the banks, but instead of big bonuses and more purchases of assets and stock by the wealthy, the people become better off by being free of debt.

Is this a good strategy?

Unfortunately the standard of financial commentary in the UK is so poor, it is unlikely to get much of an airing.

I’ve heard a theory that many financial journalists are poorly paid PR company rejects who want to get back there so whilst they are open to being fed stories about billions of recoverable barrels of oil under Gatwick, they are unlikely to ever report anything meaningful.

Dr. Mitchell,

In MMT’ model of bank reserves, what is the role of quantitative easing?

Central banks, it seems, increase bank reserves and pay interest on them.

But, as you say, these reserves do not exist to allow banks to loan money, and in the past few years, the banks have been happy to have massive excess (above requirements for transaction clearing) reserves. What are the central banks doing? Does it work?

Also, in MMT what is the role of bank deposits, since they are not the source of funds later loaned by the banks? My question refers to the money from my pay check deposited in my bank account, not the deposits the bank creates when it makes a loan.

Bernard Leikind (Tampa, FL)

Bernard

Let me give you my take on it. (Caution required)

On the user side QE swaps bonds for bank deposits. Former bondholders then choose what to with their new deposits. More bonds, equities, property, spending ? Who knows although the consensus seems to be higher market valuations for those assets.

Your bank deposits are exactly the same animal as bank deposits created from bank lending i.e. private IOUs from banks. There is no distinction. They may have had a different accounting counterpart when created but I don’t see how that is in any way significant to the user. They are merely private credits that can be used for spending, saving or gambling.

http://www.bondeconomics.com/2014/07/if-r-g-dsge-model-assumptions-break-down.html?m=1

More mainstream economics debunking.

Well It has certainly hit a nerve in the Guardian in the economic section.

They are trying to silence me and the right wing posters have had my posts removed on the issue even though I clearly provided a link to Bills work.

UK factories struggle to boost output is the story.

I am now being pre moderated by the Guardian as they can’t handle the truth.

I have cut and pasted from this Blog before to spread the word and try and get the message through. However this clearly had a link.

All the economists on there probably got taught by those very same economic text books and they can’t handle it.

It’s a gamechanger. They are not just arguing with us now they are arguing with the Bank Of England.

Derek, who has tried to silence you at the Guardian, the dreadful Rusbridger? Or one of the journalists? And which of the right wing posters have had your posts removed? I ask because although Rusbridger is economically problematic, I have not heard that anyone’s posts had been removed. Most of the Guardian’s journalists are economically illiterate, with one or two exceptions. If you are right about what you think has happened to you, something needs to be done.

Dear Phil (at 2015/06/01 at 23:34)

He is no ally. And I am no fan nor ever will be of DSGE modelling.

But the concessions made are significant because even the mainstream now is starting an internecine struggle from which the orthodox theories of banking etc cannot survive.

You will note I chose not to discuss the major part of their paper and disabused readers of it.

best wishes

bill

Dear Left Coast Bernard (now on the right coast) (at 2015/06/02 at 3:34)

Perhaps your answers will be in these two blogs from yesteryear:

QE 101

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=661

The role of bank deposits in MMT

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=14620

best wishes

bill

IMHO… as a somewhat well read commoner… Mankiw and ilk are the high priests of a religion. The math, the formulas are based upon subjective preconceived default assumptions established by the religious dogma, capitalism. The idea of making money out of thin air is not rational. It is a construct of a minority, an elite that occupy the top suite of the Pyramid Scheme and deem themselves sole arbiter of who is “worthy” of the 21st Century green-gold. It’s more or less pretty easy to distinguish this as a Religious Club run by the 1% with the Serfs in the bottom 80%, Middle Management up to the top 5% and the Royalty the .001%. All banking should be Public Banking where the People of the Commons are equally allowed surplus funds at nominal amounts and rates to activities that are beneficial to a sustainable earth and society. Capitalism is a gambling casino with restricted membership.

Let’s face it. Capitalism only works with increasing population to drive “growth”, which drives borrowing so that the top 5% can continue to profit off a “growing” 95%. (Just imagine a world of voluntary attritive population decline to 3.5 billion. Growth, capital, housing, infrastructure and all aspects of life can reset to a sustainable maintenance mode with plenty for all and NO NEED FOR HORDED WEALTH AND POWER.) Inflation is manufactured by the Royalty as a steroid to the growth stimulus of population. We have an over-full planet long since outpacing a sustainable footprint. The Capitalist Church spends massive resources keeping the commoners as dumbed down as possible so they keep in line with the program: obey, serve, die. We are now in the suicidal Death Dive with the priests and royalty partying in the drivers cab, while the commoners have their consumer culture blinders strapped in LOCKDOWN obey mode.

“I have one word for you… degrowth!”

Neil Wilson says:

Monday, June 1, 2015 at 18:36

“That’s a crowding out argument for which there is no evidence.”

B.M.’s fellow signatory to the F.T. letter of 26th March 2015 has this to say and offers corroborative econometric evidence?.

” . . . whereby the coefficient for ∆g is expected to be close to -1. In other words, given the amount of credit creation produced by the banking system and the central bank, an autonomous increase in government expenditure g must result in an equal reduction in private demand. If the government issues bonds to fund fiscal expenditure, private sector investors (such as life insurance companies) that purchase the bonds must withdraw purchasing power elsewhere from the economy. The same applies (more visibly) to tax-financed government spending. With unchanged credit creation, every yen in additional government spending reduces private sector activity by one yen. “

”

In the modern world money is simply accountancy. It’s issued by banks for production. Producers distribute it as effective purchasing-power as wages, salaries and dividends which are a part of industrial costs and prices. Industry must recover its costs through sales to the consumer and the money is then cancelled until reissued for a new cycle of production. Thus is created an endless cycle of money creation and destruction. Money is not a store of value and is increasingly a means of distribution rather than a means of exchange.

However, industry has many other costs including allocated charges in respect of real capital (plant, tools, etc.) which are not distributed as income in the same costing cycle. This creates a widening chasm between costs or final prices and effective consumer incomes-creating a deficiency of consumer income which becomes ever greater due to the increase of un-monetized capital charges in total prices. This “gap” becomes greater as the modernizing economy becomes more real capital intensive through greater use of non-labour factors of production.

This widening deficiency of effective purchasing power is met today by exponentially expanding bank debt issued to consumers, industry and governments. The gap between final prices and effective consumer incomes should not be made up by additional debt as a growing charge or mortgage agains future production. Nor should it be filled by new money derived from an excess of real exports over imports-nor from superfluous, wasteful and destructive capital and war production.

The required expansion of purchasing-power should be created without debt and distributed from a properly constructed National Credit Account to all citizens as National (Consumer) Dividends and to retailers enabling them to sell, at point of sale, at increasingly lower prices, i.e., Compensated Retail Prices, in order to reflect the real physical efficiencies achieved by industry. The banks create this necessary credit all the time as a debt owing to themselves although they do not create the real wealth of the community which they are monetizing. Yet they will foreclose on these assets if a borrower defaults on a loan. The technical term for this process is counterfeiting and it must be stopped once and for all. Modern banking is simply a colossal counterfeiting racket-so colossal that the average citizen simply cannot believe it.

The creation of money by banks is old news. It was explained by H. D. McLeod in “The Theory and Practice of Banking”, 1883. Reginald McKenna, one-time Chancellor of the British Exchequer wrote in his “Post-War Banking Policy” (1928), “I am afraid that the ordinary citizen will not like to be told that the banks, or the Bank of England can create or destroy money.” In 1924 he had addressed a Midland Bank shareholders meeting: “The amount of money in existence varies only with the action of the banks on increasing or diminishing deposits … every bank loan and every purchase of securities creates a deposit, and every repayment of a bank loan and every sale [of securities] destroys one.”

The creation of money by banks is “old hat”. What has not been properly revealed is the crime of the banks in falsely claiming ownership of the credit they create in monetizing the community’s real wealth. They have literally appropriated the community’s credit by an act of legerdemain undetected by an unsuspecting public. The whole subject was dealt with by C.H Douglas and the Social Credit movement during the 1920s on into the post-war period.”

Wallace Klinck.

Larry

I spoke with the Guardian to ask them to reinstate my posts but they didn’t they deleted the culprits posts instead. It looks like they have now created a new piece because the comments section was like a bomb site. They’ve created it under a manufacturing headline instead of business. So they have two articles saying the same thing.

They’ve left my posts on Larry Elliots and William Keegan’s threads.

I see it as progress. I’ve probably directed more people to this site which is great news and it is progress because the gGold standard COMMUNITY used to ignore us or insult us. Now they feel they have to delete us which shows we are making headway.

You can see the change. More and more people are talking and posting about MMT. Bill, Steve Keen, Warren and Stephanie Kelton videos are being linked to all the time now. There are others who link to Neil Wilsons site and Mike Normans.

This Bank Of England report is only going to help.

Larry

It happened for sure.

Just look at the comments section

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/01/uk-factories-struggle-to-boost-output

” mainstream monetary theory is erroneous”

Very polite. “Lies” is probably more correct, but I defer to the author of the blog.

If the government issues bonds to fund fiscal expenditure, private sector investors (such as life insurance companies) that purchase the bonds must withdraw purchasing power elsewhere from the economy.

It’s an accounting-challenged statement.

If government spends $10,000 more than it takes in, a deposit is created somewhere in that amount. Another deposit is debited when it sells the corresponding $10,000 security. The author of that sentence is ignoring that while cash in the form of dollars is unchanged the non-government sector has gained a $10,000 security and therefore increased its net financial wealth. Government securities are also a form of money hardly less liquid than cash given that last year in the U.S. over $160 trillion in Treasurys were traded.

“private sector investors (such as life insurance companies) that purchase the bonds must withdraw purchasing power elsewhere from the economy.”

And that is the failure right there. Life insurance companies do not withdraw purchasing power from the economy. They only get the money in the first place because somebody has already decided to save. The issuing of a government bond is a consequence of the decision to save financially – which means that the spending chain does not complete in that accounting period and therefore no taxation is raised from that spending chain.

Governments don’t decide to fund things with Gilts. They cover off those who have decided to save who have no matching private sector borrower by providing a risk free asset. Nobody who has ever bought a Gilts has ever been prevented from buying anything. There is always a liquid market in them (by virtue of market makers if nothing else) and the individual owning the Gilt has wealth which means there is a wealth effect.

It might help our communication amongst and ourselves and with others about the function of banks, loans, and deposits to revert to language used in the 1940s and 1950s, especial by Edward S. Shaw (of Gurley and Shaw fame). Shaw wrote in his classic “Money, Income and Monetary Policy” (1950) that when a bank creates a loan, this is a debit to assets matched by a credit to a “derived deposit,” which is liquidated as the borrower draws on the loan. So, of course, loans create deposits, but perhaps better to refine (or re-use?) the precision of the term “derived deposit.” On the other hand, a new depositor to a bank, with a bag of bank notes, gold coins, or even cheques, is creating, in the terminology of Shaw, a “primary deposit.” It is this idea of the “primary deposit”, especially of gold coins from the last century or earlier, that haunts economics and leads to the idea of banks loaning out (or brokering) loanable funds.

Dear Bill and fellow commentators,

If loans create deposits, then why would a bank attempt to entice consumers to open accounts and deposit money at the bank? As a commercial bank records a loans on the asset side of ledger – for consumer purchases, inventory purchases, home purchases – The bank creates, dollar-for-dollar, a deposit on the liabilities side of the ledger. If I have it correct, the bank could perform these transactions in a volume of any amount.

I realize that some of those deposits may leave as customers make their purchases, and the recipient deposits the funds in a different bank. If the liabilites threaten to drop below regulatory requirements, then the bank could borrow from the other banks with a surplus of funds.

Is the only point to attracting deposits so that the bank can meet its reserve requirements with the least expensive funds available? And if the bank creates deposits one-for-one with loans, doesn’t that mean that there are a significant surplus of excess reserves in the system?

Thanks, Joel

…or, to put it another way, what prevents a small community bank from making a multi-billion-dollar loan to a viable project at a risk-adjusted interest rate? After all, the $10 billion loan creates $10 billion of deposits. I think I am missing a key piece of the puzzle, but am unsure what.

Thanks, Joel

Joel

Attracting deposits is less expensive than borrowing from another bank I would think.

And plenty of loans do go bad.

And remember when banks are reluctant for whatever reason, to lend to another bank, a shortage of reserves could spell the end for the bank that is short eg Northern Rock in the UK.

Neil and Ben, thanks for your comments.

Thanks Andy, I suspect that what you describe is the reason why.

Sincerely,

Joel