For years, those who want selective access to government spending benefits (like the military-industrial complex…

Seeking zero fiscal deficits is not a progressive endeavour

There was a most extraordinary Opinion piece in the British paper The Independent last weekend (June 13, 2015) – Labour should have managed the economy better when in power. It was written by the aspiring Labour spokesperson on business, innovation and skills, one Chuka Umunna, who in the days following their electoral loss advanced his name for leadership. His outlook, inasmuch at it represents where the British Labour Party is heading will render them irrelevant for years to to come (the Tories do this stuff better) and is almost indistinguishable from the growth strategy advanced by the Conservative Australian government in its most recent fiscal statement – more private debt driven by fiscal surpluses. We have been there before – it turned ugly as it always was going too. It is quite clear that comprehension of basic macroeconomics is light on the ground when it comes to Umunna and his ilk. A very sorry state.

The Australian government’s growth strategy announced in the May fiscal statement is clear – it wants to hack into public spending and exhort households and firms to make up the gap by borrowing more and putting the funds into housing.

Its as crude as that really. Last week, the Australian Treasurer claimed that property prices in Australia were not too high and, in the context of the rapidly inflating property market that (Source):

The starting point for a first homebuyer is to get a good job that pays good money. And if you’ve got a good job and pays good money and you have security in relation to that job, then you can go to the bank and you can borrow money. And that’s readily affordable, more affordable than ever to borrow money for a first home now than it’s ever been.

In defending his acerbic claims that housing was still affordable for those with the right motivations he thinks people should be out there borrowing to the hilt at a time when households are carrying record levels of debt after a decade or more prior to the GFC of credit bingeing.

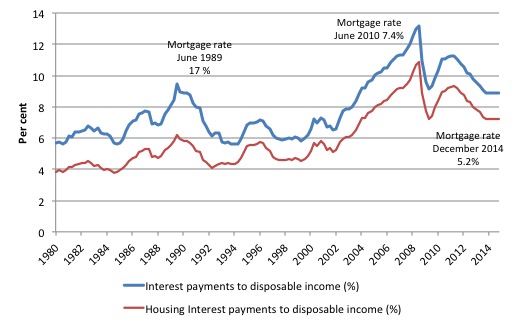

It is true that interest rates have never been lower in Australia but the interest burden remains high (see graph below) because the average mortgage is now much greater than in the past. Compare the situation at the end of last year (most recent data) when the average mortgage rate was around 5.2 per cent with the situation in June 1989 when the interest rate was 17 per cent!

The other point is that with the massive debts already being carried by homebuyers, the situation will become worse when the RBA, at some point, starts pushing up rates again and house price rises start to taper.

Then things will start to get really ugly for those on the cusp of solvency already given the size of the debts they are carrying. I have also pointed out before that many younger families buying exorbitant houses on the fringes of the cities (because they cannot afford inner-city housing) rely on two incomes with the second earner being typically a casual worker (the female).

If the economy was to slow any further, the casual hours on offer will be the first line of adjustment for firms. These families, already at the limit, soon go overboard.

Any shift in interest rates upwards also has this effect.

With economic growth well below trend and unemployment high, and given that the external sector is draining spending, there is a need for Governments to be supporting private saving with increased public spending.

The obsession with cutting public spending to achieve surpluses can only mean that the government wants the private domestic sector to take on more debt than it already has to drive growth.

It is an idiotic strategy.

But it is one that presumably Mr Umunna in Britain will endorse for the Labour Party should it regain office in the future. That is the gist of his article in The Independent at the weekend (cited above) although I doubt he knows enough about macroeconomics to connect the dots properly.

He was reflecting on the reasons that British Labour lost the recent election – at a time when the Tories had delivered a poor performance over the last five years in office.

He claims that neither side of politics has “yet fully learned the lessons of the Noughties boom or the 2008-09 bust”. I agree, especially when we read on and see what he thinks it all meant.

He then wrote:

In 2007, before the crisis hit, the UK government was running a deficit. By historical standards, it was small and uncontroversial – it averaged 1.3 per cent from 1997 to 2007, compared with 3.2 per cent beforehand under 18 years of Tory rule. And yet to be running a deficit in 2007, after 15 years of economic growth, was still a mistake. My party’s failure to acknowledge that mistake compromised our ability to rebuild trust in 2010 and in 2015. If a government can’t run a surplus in the 15th year of an economic expansion, when can it run one?

Which tells all and sundry that Mr Umunna (or the economists who wrote the article for him) have no idea of how the macroeconomy really works.

What do we know about 2007-08? Well the fiscal deficit was 0.44 per cent of GDP and it accompanied an external deficit of 1.2 per cent of GDP.

In other words, the net contribution to demand from the government sector was not sufficient to offset the drain on demand from the external sector and as a consequence the private domestic sector continued to run a deficit (spending more than its income) of 0.8 per cent of GDP.

The private domestic deficit had fallen in the years leading up to 2007 but the household saving ratio (as a percent of disposable income) was still negative and had been negative since the December-quarter 2004. It only turned positive again (that is, households resumed saving) in the December-quarter 2008 as the reality of the crisis started to dawn on the excessively indebted British households.

The private investment ratio (capital formation as a percentage of GDP) had also fallen from 19.8 per cent in the second-quarter 2000 to 18.8 per cent in the December-quarter 2007.

So the dynamics of the private domestic deficit were being largely driven by household dissaving and increasing their indebtedness.

The economy was growing but in an unbalanced way – too much private debt and too small public deficits.

The statement “If a government can’t run a surplus in the 15th year of an economic expansion, when can it run one?” implies that there is something inevitable about a government running a fiscal surplus, just because there is on-going growth.

It seems to escape Mr Umunna’s grasp that the continuous growth was aided by the fiscal deficits and would have come to a crunch much earlier, given the private debt escalation, had the government tried to run a fiscal surplus.

To answer his question, a nation can safely run a fiscal surplus if the external sector is adding so much to spending in the domestic economy that the government can provide an appropriate level of services and the desires of the private domestic sector to save can be met.

Continuous growth that was associated with relatively large external deficits and unsustainable private sector credit expansion, would not suggest a fiscal surplus was appropriate, especially when there was not evidence that the British economy was operating at over-full employment (small output gaps).

So in what sense was it a mistake for the government to be running a deficit even though there had been a long period of growth (presumably supported, in part, by the deficits)?

Presumably, the growth and high employment levels meant that the fiscal deficit that was remaining was not of a cyclical nature (that is, driven by movements in the automatic stabilisers because tax revenues were well below high employment levels).

The question then is whether the ‘structural component’ of the fiscal balance (reflecting the discretionary spending and taxation choices of government) is appropriate in relation to achieving full employment given the choices made by the private sector and the external sector.

Given the data above, it is clear that the fiscal deficit in 2007-08 was probably too small but a surplus would have been irresponsible.

Please read my blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – for more discussion on this point.

Umunna then excelled in his ignorance with this gem:

Our goal now must be to show that we have learned the lessons from this past … It starts by asserting again and again that reducing the deficit is a progressive endeavour – we seek to balance the books because it is the right thing to do.

Of course, he offers no insights as to why this is the right thing to do for Britain.

How is he going to create external surpluses that are of sufficient magnitude to meet the desires of the private domestic sector to net save, while at the same time, ensuring overall spending is sufficient to achieve full employment and allow the government sufficient spending scope to provide first-class public services and robust public infrastructure development?

Given history and the current circumstances, I would think an on-going fiscal deficit – larger than it is now – is the “right thing to do” if the well-being of the British people is to be advanced.

Britain will not generate large external surpluses in the foreseeable future, which means the only way that the private debt situation can be brought under control without driving the economy back into recession, is for the government to increase its fiscal deficits.

The rest of his article talks is full of motherhood statements about improving productivity, exports, being pro-business and all the rest of the guff.

But none of that is achievable (or sustainable) unless the British Labour Party starts to understand that they cannot rely on increasing private indebtedness to drive growth. And once they realise that, they will understand that the alternative is that fiscal deficits have to support the private sector’s debt reductions.

Umunna should read the Bank of England article – Household debt and spending – which appeared in the third-quarter 2014 edition of its Quarterly Bulletin.

The research reported was the “first study to use microdata to assess the role of debt levels in determining UK households’ spending patterns over the course of the recent recession”.

It demonstrates that:

high levels of household debt have been associated with deeper downturns and more protracted recoveries in the United Kingdom.

It traces “the build-up of household debt” in the UK before the GFC from around 100% of income in 1999 to 160 per cent in 2008. The same sort of dynamic occurred in Australia as a result of the property boom here.

It also notes that the “capital gearing” ratio, which is the “measure the stock of debt in relation to the value of assets” rose dramatically before the crisis because asset prices fell sharply.

The significant part of the Bank’s research pertains to the contention that rising household debt levels reduce household spending in aggregate. By way of theoretical motivation for the idea, they note that if:

… indebted households, who had borrowed on the expectation of higher future income, suffer adverse shocks to their future income expectations that lead them to consume less and repay debt. Even if other households experience offsetting positive shocks, they do not increase consumption by enough to fully offset the effect on aggregate spending.

What is the evidence for this contention? Even though the rise in household debt in the UK was “largely matched by a build-up in assets” the evidence is that:

… across countries, recessions preceded by large increases in household debt tend to be more severe and protracted, but there is less evidence that the level of pre-crisis debt is a good predictor of the subsequent adjustment in spending.

The UK evidence supports the international findings. The research finds that “UK households with high levels of mortgage debt made larger adjustments in spending after 2007”. The reductions “in spending were more modest for those with debt to income ratios below 2”.

Prior to the crisis, the spending by highly indebted households grew faster than for other groups. It was mostly on “durables and non-essential categories of spending” and after the crisis the spending cuts in these areas were large.

The researchers thus find that “highly indebted UK households’ spending appears to be more sensitive to economic shocks” which means that a growth strategy relying on rising household indebtedness from already elevated levels is likely to be highly unstable and lead to a deep unwinding when the cycle turns.

The reasons advanced for the large post-crisis cuts in spending by highly indebted households included:

1. “Highly indebted households were disproportionately affected by tighter credit conditions”.

2. “Highly indebted households became more concerned about their ability to make future repayments”.

3. “Highly indebted households may have made larger adjustments to future income expectations”.

The implications of the research are clear.

Once the private domestic sector becomes highly indebted relative to its income, the consequences of changes in the economic environment – for example, a downward revision of future income expectations as a result of uncertainty with respect to employment etc – will generate much larger downturns and more protracted recoveries.

The UK profile since 2008 supports this view as does the Australian experiences, both nations with highly indebted households.

Conclusion

The results thus indicate that the pursuit of fiscal surpluses which might lead to declining public debt to GDP ratios (because no new debt is issued yet GDP grows) as long as private spending is strong enough as a result of rising indebtedness, will run the significant (almost certain) risk of precipitating a major recession.

Mr Umunna appears to be blithely unaware of these dynamics and the sectoral relationships at the macroeconomic level, which dictate, as a matter of national accounting, that a government surplus must lead to a non-government deficit.

The latter must mean rising non-government indebtedness, which is eventually, unsustainable and as the Bank of England’s research shows creates larger swings and weaker recoveries the more indebted the private sector becomes.

Despite Mr Umunna’s assertions, it is not “a progressive endeavour” for a government to “seek to balance the books”. It is more like a certain recipe for entrenched unemployment and stagnant income growth.

The British Labour Party should expunge these sorts of positions from their policy platform.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

UK Labour is currently going through its “Iain Duncan Smith” phase.

Chukka and Liz Kendall are there to make Andy Burnham look like he’s a little bit progressive in outlook because he probably won’t privatise the NHS entirely.

Very clever of Mandelson to give these Red Tories a platform.

Dear Bill

People like you are at a huge disadvantage because what you say seems to most people an affront to common sense. Most people think that a household is doing well when it saves. They apply the same logic to the government and the country as a whole, and then draw the conclusion that government and current-account surpluses are a good thing. Politicians who have to explain sectoral balances and monetary sovereignty on the campaign trail would be vulnerable to attack by the believers in “common sense”. It is one thing to be intellectual right, but quite another to be electorally right.

Heiner Flassbeck had a recent posting on his blog in which he demonstrates why a country like Germany, with its endless current-account surpluses, can’t be a model to the world. The book you wrote with J. Muysken is among his recommended further reading.

Regards. James

Here in Canada we have a federal government bent on making balanced bugets the law of the land forever; and, even Liberal provincial governments working feverishly to undo a century worth of progressive efforts to keep the rentier positions out of private hands or build public assets, to help make it so ( currently they are about to sell off the silverware, I mean, privatize Hydro One in Ontario). They all look at you like you like you come from a different planet when you try to discuss this from the MMT perspective.

It’s difficult to tell if politicians really don’t understand or if the ignorance is theatrics. One candidate, who has an economics degree, answered “I am a Liberal not a Neo Liberal” when asked about opposing the Neo Liberal approaches. He then proceeded to introduce typically Neo Liberal language involving inflation risk etc into our discussion about maintaining enough deficit for a job guarantee. I talked about MMT a bit. I don’t know if any of it made an impression; you can lead horses to water but you can’t make them drink.

I agree with James when he distinguishes between being intellectually right versus electorally right. It’s therefore an ideal time now for Labour to get its economic house in order. The road ahead will be a hard slog and turning around the ship of ignorance a mighty endeavour! They can chip away at the prejudice. Sooner or later the tories will see the danger, since after all it is not a theory to be proved or disproved and their attacks will change to match. By then though the game will will be over. The next 5 years will be crucial for labour as they extricate themselves from being another tory party to one with genuine messages of hope. Other economies might make a move and any such event will support Labour. Here in Oz the mindset in both major parties is just as rigid as in the UK, so not much help will come from here.

J. Christensen is right to say “It’s difficult to tell if politicians really don’t understand or if the ignorance is theatrics.”

To answer that question it would be very useful if some polling organisation or similar could so a series of “off the record” interviews with the politicians who spout “Osborne / Ummna” rubbish, so as to find out what they really think. It’s possible that 90% of those advocating permanent budget surpluses know perfectly well they’re lying to their teeth, in which case we could all sleep more soundly.

Flassbeck and Lapvitsas have a book coming out in September:

Against the Troika: Crisis and Austerity in the Eurozone By (author) Heiner Flassbeck, By (author) Costas Lapavitsas, Foreword by Oskar Lafontaine, Preface by Paul Mason (Verso).

Lapavitsas has previously published a critique of the Euro mechanism in 2012, contending that impoverished states should leave the Eurozone, as its neoliberal policies are inherently contradictory and, therefore, impossible to achieve what its supporters claim they want.

Liz Kendall has recently said that the Labour Party must support the creation and maintenance of surpluses. This is akin to what Osborne said in his Mansion House speech and is idiotic. It would condemn the UK to underemployment equilibrium in perpetuity. I have been told that the upper strata of the Labour Party are all singing from this same hymn sheet. With the possible exception of Jeremy Corbyn, who was previously a trade unionist. But I have also been told that he is too left for the party and, thus, has little chance of winning the leadership election. Ye gods.

To put it short, the social state is not possible with a balanced budget.

Bill said: “The obsession with cutting public spending to achieve surpluses can only mean that the government wants the private domestic sector to take on more debt than it already has to drive growth. ”

Their obsession with cutting public spending can mean what you have elaborated above Bill, or alternatively it can mean that the government as a whole is economically illiterate, that is .. it does not understand basic macroeconomic principles and is out of its depth (i.e. does not know what it is doing).

@John Hermann

John, I have told people that, for instance, that everyone of the Labour leadership is economically illiterate. and have been met with incredulity. No one can quite believe that they are ALL economically illiterate. But I try to show that that is in fact virtually the case with as many examples as I can think of, but it is like trying to swim through treacle. They are more readily open to the claim that most journalists are economically illiterate, especially if you mention at least one who isn’t. Unfortunately, for the Labour Party, this is becoming more difficult by the day.

My MP is a LibDem, who just happens to be a good local MP. He is open to new economic ideas. But then he has nothing to lose by so doing. You might think the Labour Party would be feeling similarly. Seemingly, not yet. What will it take?

It is likely to be the wrong approach to go to the economics.

What you need to do is sell a vision to people.

We have all the silver. Would you like a living wage, paid weekly for a reasonable week’s work? Would you like a decent pension when you retire that you don’t have to worry about? Would you like to retire much earlier than 67? Would you like a decent home that you can afford to keep warm?

If you do then we can create a society where that happens.

If you run a business would you like competition eliminating that undercuts you with poorer wages, training and employment opportunities? Would you like people to have money in their pockets so they can buy what you produce? Would you like government to invest in basic research, development and infrastructure made freely available so that you have more opportunities to profit. Would you like banks that are geared towards lending to businesses – because they have been banned from playing casino games.

MMT is just the box of lego. We need to build something from that that inspires people and is directly relevant to their lives.

“It is true that interest rates have never been lower in Australia but the interest burden remains high (see graph below) because the average mortgage is now much greater than in the past. ”

Lower interest rates get sucked up as higher prices.

Neil @1:26,

You have outlined a very good series of questions that imply the potential for alternative ‘states of the world’, at least in those societies which establish and conserve their monetary sovereignty. Posing these questions in a personal way, as you have done, is a good way to solicit genuine consideration of situations that people otherwise dismiss as “abstractions” or “beyond my control”.

I would add one more to your list that occasionally generates some thinking in the general public context, i.e. “Do you want decision makers in our public and private sectors to stop wasting resources that are (or could become) available to us in the market?” Mine is a wordier style than yours; maybe “Do you hate waste, and the policies (and/or attitudes, and/or beliefs) that cause it?” is better.

I share your view on the approach to general publics. Parables and images stick better than logic for general audiences, even when the logic is impeccable and well explained. Open-minded academic and policy wonk audiences will not be won over without “the economics” however, so MMT thinkers have to do that too. I think I once heard a parable about “walking and chewing gum at the same time” that probably applies. 🙂

Neil, what you say sounds sound to me. I would think you are right that this is the way to go. The other way doesn’t seem to work.

@Neil Wilson,

I think you are on the right track in asserting that using the economic logic of MMT is unlikely to cut through and this is due to the dominance of the prevailing paradigm, the counter-intuitiveness of MMT and the fact that most people will have difficulty grasping the full import of MMT.

I really like the simple vision approach that could genuinely appeal to people fearful of the future under the current paradigm and offers a much more positive and uplifting narrative than the bleak and sterile ideology of Neo liberalism.

The vision, along the lines you have put forward would clearly need to be further developed and would need to be supported by an easy to understand outline of MMT. That is only one of the challenges. Finding a leader who can absorb and skilfully articulate it in terms most can understand is another. That leader would also need to have a strong grasp of MMT to withstand the inevitable attacks and ridicule.

Like the style expressed in the following link:

http://www.nextnewdeal.net/deficit-nine-myths-we-cant-afford

Populism is just a step in the downfall of Democracy as per the Machiavellian governmental cycle. The only way to save Democracy from itself is to have the electorate educated enough to be able to make informed decisions, otherwise why not just simply do away with the electorate?