During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to…

Greece – now the conservatives are denying there was austerity

The Project Syndicate recently (August 6, 2015) published an Op Ed by conservative Edmund Phelps – What Greece Needs to Prosper. The article was widely syndicated by the conservative media and represents part of the conservative narrative to conveniently revise history when the facts violate the conservative ideological agenda. It is an appalling article. We are now in a phase of “Austerity denial”, where conservatives attempt to massage history to avoid the unpalatable conclusion that the massive austerity that has been imposed on certain countries by the IMF and its partners in crime (in Greece’s case the European Commission and the ECB) has caused huge declines in GDP (levels and growth rates) and deliberately led to millions of people becoming jobless with associated rises in poverty rates. That causality is undeniable.

Phelps’ credibility is immediately strained by this opening gambit where he seeks to denigrate ‘Keynesian’ economists:

Looking at Greece, these economists argue that a shift in fiscal policy to “austerity” – a smaller public sector – has brought an acute deficiency of demand and thus a depression. But this claim misreads history and exaggerates the power of government spending.

Much of the decline in employment in Greece occurred prior to the sharp cuts in spending between 2012 and 2014 – owing, no doubt, to sinking confidence in the government.

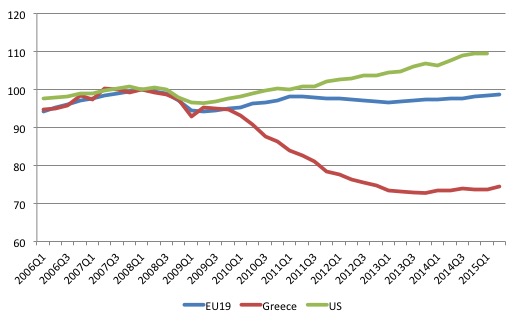

This graph might help put that ‘stupid’ inference into perspective and begin the discussion. It shows real GDP indexed at 100 in the first-quarter 2008 (the peak) for the 19 Eurozone nations, Greece and the US from the March-quarter 2006 to the March-quarter 2015. The data for Europe is from Eurostat. The US data comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Prior to the crisis, Greece was growing in line with the rest of the Eurozone. The turning point from the peak is identical for the Eurozone in general.

The downturn and the slight recovery (as the deficit grew to attenuate the loss of private spending) that followed the same pattern in Greece as it did in the Eurozone.

Then the break point came – March-quarter 2009 – and from there the Greek disaster began and has continued to the current period.

The difference experiences of the Eurozone in general and the US reflect the imposition of austerity in Europe relative to the US, where the fiscal deficit was allowed to remain at relatively higher levels for longer to support growth in private spending. The result was that US real GDP recovered more quickly and is now 10 per cent above the pre-crisis peak.

The EU19 real GDP has still not passed its pre-crisis peak. Greek real GDP is now 26 per cent below their peak.

If you believed Phelps, the massive decline in the Eurozone in general and presumably the US, where the turning points match those of Greece, occurred because of “sinking confidence in the … [Greek] … government”.

This is idiocy.

The break point came when the Greek government started to impose fiscal austerity in an environment when private spending was extremely weak and deteriorating further.

A sequence of events including the Troika bailouts built on that austerity and caused real GDP to fall by around 26 per cent.

That is beyond doubt.

Phelps also claimed that:

Looking at Greece, these economists argue that a shift in fiscal policy to “austerity” – a smaller public sector – has brought an acute deficiency of demand and thus a depression. But this claim misreads history and exaggerates the power of government spending.

He had earlier said that “these economists” considered “employment is determined by “demand” – government spending, household consumption, and investment demand”.

The economists who consider employment is demend-determined do not consider the crisis in Greece to have been caused by austerity.

That construction of the problem is just a convenient fiction set up by Phelps to try to fit the data to this ideological mission.

The reality is that the crisis was initially engendered by a collapse in non-government spending – private investment, followed by private consumption and compounded by a drop in world export trade.

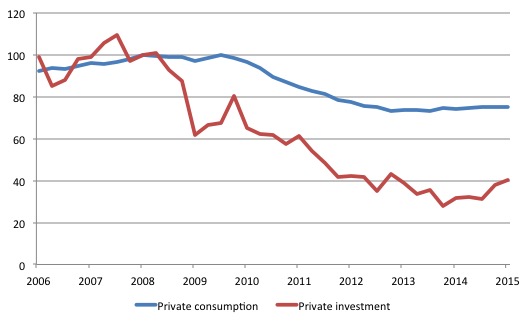

The following graph shows the evolution of private spending (Consumption and Investment) from the March-quarter 2006 to the March-quarter 2015. The index equals 100 in the March-quarter 2008.

Clearly, investment led the crisis in 2008 and 2009 as financial markets froze in the wake of the American housing disaster. As employment fell and incomes started falling, private consumption started to fall.

The government started to cut spending in 2009 and then accelerated the cuts in early 2010 at a time when private spending was still deteriorating, meaning fiscal policy became pro-cyclical when responsible policy conduct should see counter-cyclical fiscal intervention.

In other words, when the private spending cycle is contracting and unemployment is rising, public spending should expand, and vice versa.

The conduct of Greek fiscal policy once the crisis hit was irresponsible and the austerity that was imposed exacerbated the contraction that was led by the collapse of private investment.

I will return to the facts later.

Theoretical flaws

Phelps, typical to form, attempts to convince his readers that the meltdown in the Greek economy had nothing to do with the harsh austerity that was imposed on the nation as a result of the enforcement of the fiscal rules under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and then the Troika’s bailout conditions.

He attacks economists who think that “employment is determined by “demand” – government spending, household consumption, and investment demand”.

That is, he denies that spending is related to output in any way and that firms hire workers to produce output and if there are no sales the firms will not hire.

He has made a career out of such denial. His earlier work in the late 1960s sought to attack the concept of ‘involuntary unemployment’ that is one of the central contributions derived from Keynes’ General Theory.

This has been a long-standing dispute within economists.

Involuntary unemployment is a fundamental concept in macroeconomics and indicates that individuals are constrained by the systemic failure of the economy to provide enough jobs and have little power to alter that circumstance and thus gain work.

Phelps is among the neo-classical economists who consider mass unemployment to be a voluntary state, chosen by individuals upon the basis of their preferences for “leisure” against work.

The concept of voluntarism comes from the Classical economists (pre 1930s) who denied that there could ever be an enduring state where the system failed to provide enough work relative to the preferences of those who desired to work.

They claimed that output (which drives the demand for labour) could never persist at levels which would be insufficient to generate a job for all those who desired one.

The Great Depression in the 1930s changed the debate because the notion of voluntary unemployment failed to accord with the observed reality.

Millions of workers clearly desired to work but were forced onto the unemployment queue because employers were not willing to provide them with jobs. It was clear that the firms had no desire to expand employment at that time because they could not foresee any potential sales for the extra output that might have been produced.

In the 1930s, the British economist John Maynard Keynes realised that the existing body of macroeconomic theory was inadequate for explaining the mass unemployment that persisted throughout the decade as production levels fell in the face of a major slump in overall spending. He thus defined involuntary unemployment in this way:

Men are involuntarily unemployed, if, in the event of a small rise in the price of wage-goods relative to the money-wage, both the aggregate supply of labour willing to work for the current money-wage and the aggregate demand for it at that wage would be greater than the existing volume of employment. (Page 15, General Theory)

It is true that definition was somewhat tortured.

It was deliberately framed in this way to challenge the existing British Treasury viewpoint which claimed that the unemployment during the early part of the 1930s was due to the real wage (the purchasing power equivalent of the money wage) being too high relative to productivity.

So Keynes said that if the real wage falls and workers still supply more labour to the increased quantity of jobs offered by the firms then those workers were unemployed against their will – that is, involuntarily unemployed.

The essential point that Keynes was aiming to instill into the debate was that mass unemployment of the type he saw in the 1930s was a demand (systemic lack of jobs) rather than supply phenomenon (choice by workers for more leisure).

That is, it is total spending in the economy that impels firms to employ workers and produce goods and services. A firm will not employ if they cannot sell the goods and services that would be produced.

Building on that concept, Keynes introduced the idea of the unemployment equilibrium – that is, a state where the monetary economy could continue to operate at high levels of unemployment and firms realising their expected sales volumes.

He argued that if the economy reaches this type of impasse, the only way out is to reduce unemployment by an injection of government spending, which stimulates demand and provokes firms to increase output and offer more jobs.

Edmund Phelps was among a group of economists in the late 1960s that resurrected the voluntary unemployment narrative as part of their campaign to disabuse governments from running deficits and avoiding deregulation.

It was really the start of the modern neo-liberal period in economics.

I won’t go into detail but Phelps introduced a stylised model of the economy based on a series of ‘islands’ (one day travel apart) where obtaining information about wage and employment conditions on other islands is a costly exercise – a worker has to travel to a new island to receive a wage offer and in doing so forgoes a day’s wage.

Each day, there is an auction on each island which determines the wage and employment to prevail. All workers available can get a job if they are prepared to work at the free market (auction) wage.

The worker is then constructed as having a choice. Does a worker accept the current market wage on their island or incur the costs required to find a better offer elsewhere.

So when wages are considered ‘low’ relative to what the workers believe prevail on other islands, the workers will get in a canoe and paddle to a neighbouring island to seek a higher real wage on another island.

AS a consequence, the unemployment that is recorded as the workers canoe around the various islands is purely voluntary – workers trying to access higher wage offers when there is imperfect information.

The implication is that a worker can always generate a wage offer (that is, a job) if they are prepared to work for lower wages.

This conception considers wages to be only a cost. But wages are also a major source of income and hence spending capacity. Cut wages and incomes fall even though for firms costs might fall.

The mainstream economists ignored the income side of the wage deal. The technical issue comes down to the flawed assumption that aggregate supply and aggregate demand relationships are independent. This is a standard assumption of mainstream economics and it is clearly false.

Phelps’ conception of wages and employment falls into the trap of the Fallacy of Composition, which refers to errors in logic that arise “when one infers that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true of some part of the whole (or even of every proper part)” (Source).

So the fallacy of composition refers to situations where individually logical actions are collectively irrational.

These fallacies are rife in the way mainstream macroeconomists reason and serve to undermine their policy responses. The current push for austerity across the globe is another glaring example of this type of flawed reasoning. The very fact that austerity is being widely advocated will generate the conditions that will see it fail as a growth strategy. We never really learn.

The point is that prior to this the mainstream economists assumed that what might happen at an individual level will also happen if all individuals do the same thing.

In terms of their solutions to unemployment, they believed that one firm might be able to cut costs by lowering wages for their workforce and because their demand will not be affected they might increase their hiring.

However, they failed to see that if all firms did the same thing, total spending would fall dramatically and employment would also drop. Again, trying to reason the system-wide level on the basis of individual experience generally fails.

The upshot is that at the theoretical level, the sort of models that Phelps and his cronies were wheeling out, which have dominated mainstream economics and poisoned the minds of tens of thousands graduate students over the last 45 years or so, fail basic logic tests and cannot provide a satisfactory explanation for mass unemployment.

The Facts!

Let us just record the Phelps’ facts:

1. There was no austerity in Greece

2. “Much of the decline in employment in Greece occurred prior to the sharp cuts in spending between 2012 and 2014 – owing, no doubt, to sinking confidence in the government”.

3. “Greek government spending per quarter climbed to a plateau of around €13.5 billion ($20 billion) in 2009-2012, before falling to roughly €9.6 billion in 2014-2015”.

4. “the number of job holders reached its high of 4.5 million in 2006-2009, and had fallen to 3.6 million by 2012”.

5. “By the time Greece began to cut its budget, the rate of unemployment – 9.6 per cent of the labor force in 2009 – had already risen almost to its recent level of 25.5 per cent.”

6. “They indicate that Greece’s turn away from the high spending of 2008-2013 is not to blame for today’s mass unemployment.”

If we were to summarise in different words, the Greek government was spending strongly through to 2012 yet the unemployment rate was already around 25 per cent before the spending cuts occurred.

There are so many things that are wrong with this story not the least being Phelps’ facts do not seem to accord with the actual data available from Eurostat, the IMF, the OECD or Greece’s own El.Stat.

It is one thing to attempt to impose an ideological lens onto history. But another to alter the facts so that they fit the rigid ideological lens.

Why Project Syndicate would lower its standards by publishing this sort of nonsense is beyond me.

Here are some facts.

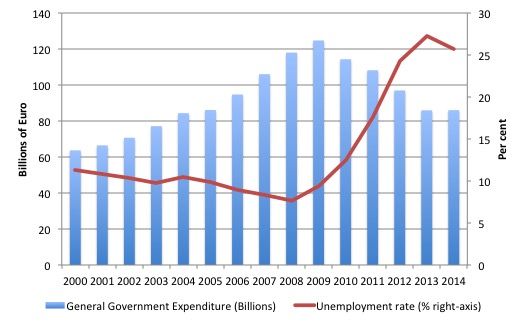

The first graph shows Greek total general government expenditure (billions of euros) (blue bars) and the unemployment rate (per cent) (red line) from 2000 to 2014.

The data is from the IMF World Economic Outlook.

Points to note:

1. Government expenditure peaked in 2009 and fell sharply after that.

2. The unemployment rate fell steadily as government expenditure increased and started to rise again in 2009. After the government started cutting expenditure the unemployment rate accelerated upwards.

At the peak government expenditure level (2009), the unemployment rate was still only 9.461 per cent

Note, that Phelps is talking about government expenditure one moment and then without warning starts to talk about the “budget” (“cut its budget”), which means we are talking about the balance between revenue and expenditure or the fiscal deficit.

So was the unemployment rate near to 25 per cent by the time the fiscal deficit started to contract as a result of austerity?

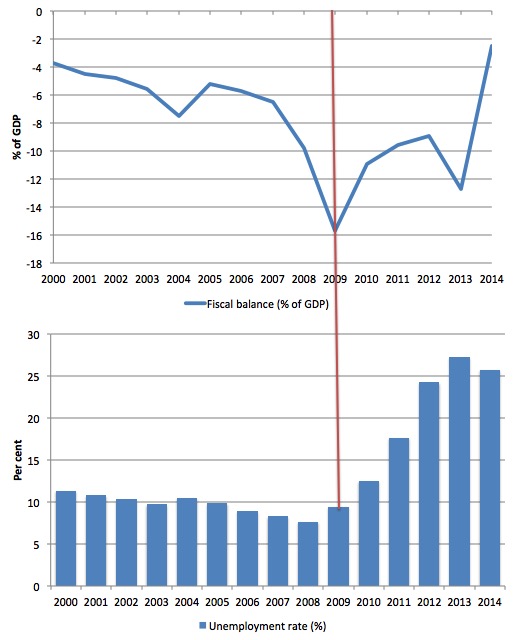

The upper panel of the following graph shows the shift in the fiscal balance (negative indicates deficit) as a percent of GDP (blue line) and the lower panel shows the unemployment rate (%) between 2000 and 2014.

The red vertical line is there for those who cannot interpret a turning point!

The fiscal balance began being tightened (austerity) in 2009 not 2012 and that was the year that the unemployment rate started to rise sharply. As the austerity was intensified the unemployment rate rose sharply.

Facts!

But it is here that Phelps gets tricky.

Phelps wrote:

Another finding casts doubt on whether austerity actually was imposed on Greece. Government spending has certainly fallen – but only to where it used to be: €9.6 billion in the first quarter of this year is, in fact, higher than it was as recently as 2003. So the premise of austerity appears to be wrong. Greece has not departed from past fiscal norms; it has returned to them. Rather than describing current government spending as “austere,” it would be more correct to view it as an end to years of fiscal profligacy, culminating in 2013, when the government’s budget deficit reached 12.3 per cent of GDP and public debt climbed to 175 per cent of GDP.

You will note that the fiscal deficit rose again in 2013 after contracting from 2009 to 2013 as the austerity was imposed.

The deficit then rose again in 2013 to 12.2 per cent of GDP (as Phelps notes). Phelps tries to represent this reversal in the fiscal deficit as the “culmination” of “years of fiscal profligacy”. Which is a straightforward misrepresentation of the fiscal dynamics and he must know that.

He also knows that the vast majority of readers will not understand the underlying dynamics and will see the rise in the deficit as a relaxation or worse of austerity.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

In 2012, general government expenditure in Greece fell by 10.4 per cent and in 2013 11.4 per cent. So government spending was in retreat.

The reason that the deficit rose again is because the decline in tax revenue also accelerated from 2011 through to 2013 because the austerity had created a worse recession and the sharp decline in economic growth undermined the tax base.

The general point is that while the government was cutting its discretionary expenditure and increasing taxes (the austerity policy), the automatic stabilisers (the links between the fiscal balance and the state of economic activity) were pushing the fiscal deficit out faster than the austerity was cutting it.

This is the classic policy failure and illustrates why it is folly to target a lower deficit with discretionary austerity when private spending is weak. What often happens is that as the austerity is undermining growth, the fiscal deficit increases and unemployment rises. Bad on bad!

The other point to note is that Phelps adopts a very odd definition of the concept of ‘austerity’. Refer to his claim that:

Government spending has certainly fallen – but only to where it used to be: €9.6 billion in the first quarter of this year is, in fact, higher than it was as recently as 2003. So the premise of austerity appears to be wrong. Greece has not departed from past fiscal norms; it has returned to them.

Austerity is not a historically comparative concept. It relates to directions of flows of net government spending (the balance between spending and taxation) in relation to the current non-government net spending and the extent to which there is currently excess (idle) productive capacity.

It it true that government spending rose in the early days of the Eurozone and peaked in 2009. By 2014, it was back, in absolute terms to its 2005 level, while GDP was back to its 2000 level, such has been the contraction in the economy.

But between 2009-2014, government spending has contracted by an incredible 32.1 per cent, while private consumption fell by 22.4 per cent, total investment fell by 41 per cent.

In each of the years spanning that period, private spending was contracting, idle capacity was rising and government spending was contracting.

The only time that the government net contribution in that period was not undermining was in 2013, as noted above, and that was because tax revenue collapsed faster than the spending was being cut.

That is austerity – the overall impact of the government sector between 2009 and 2014 was to reduce economic growth.

To establish that conclusion, we do not have to consider what spending levels were previously.

The conclusion would still hold even if the Greek government had have gone on a spending frenzy prior to the crisis which pushed the economy to achieve unrealistic nominal growth rates and was now returning to previously sustainable growth.

The only point we have to establish is that the direction of net government spending is undermining economic growth at a time when non-government spending was incapable of bridging the output gap. That certainly has been the case in Greece between 2009 and 2014.

The other clue – which also rejects the claim that the Greek government was on a hell-bent spending frenzy before the crisis, which as I noted, is a separate issue to establishing whether austerity has been imposed post-crisis, is to examine the inflation rate evolution.

The IMF data tells us that the inflation rate varied between 3 and 4 per cent between 2000 and 2009 which was slightly higher on average but hardly out of kilter with other Eurozone nations. The Eurozone also experienced the little spike to 4 per cent in 2008 just before the crisis hit.

So relative to productive capacity, Greek government spending does not appear to have been wildly excessive.

The analysis by Phelps then deteriorated further. He wrote that:

The “demand school” might respond that, regardless of whether there is fiscal austerity now, increased government spending (financed, of course, by debt) would impart a permanent boost to employment. But Greece’s recent experience suggests otherwise. The huge rise in government spending from 2006 to the 2009-2013 period did produce employment gains, but they were not sustained.

Note, the “rise in government spending … did produce employment gains”.

But they were not sustained because:

1. Greece was affected by a world-wide recession instigated by the collapse of the US housing market. This led to a major decline in private spending (investment first, then consumption) and employment growth was wiped out.

2. Then the government significantly cut spending to exacerbate the decline in private spending.

Does he really think people are that stupid and gullible not to understand these dynamics.

His real aim is to disabuse anyone from supporting fiscal expansion.

He claims that “spending more is not the remedy for Greece’s plight, just as spending less was not the cause”.

He fails (as we have seen) to establish the second part of the proposition, and his explanation for opposing spending expansion becomes more bizarre than his earlier denials.

He claims that to fund that extra stimulus, foreigners would not be willing to buy the debt so Greeks, themselves would buy it.

This would mean that:

… household wealth relative to wages would soar, and the labor supply would shrink, causing employment to contract

So Phelps is trying to convince his readers that because Greek households would be exchanging their saving deposit for a government bond – which is just a portfolio shift in their wealth holdings, there would be a major shift in the preference of Greek households to work, which would lead them to withdraw their labour and live on the income flows coming from the bond holdings.

Note that the only gain from holding the bonds, presuming that the household was not aiming to become a speculative bond trader in the secondary markets, would be the extra income flowing via the yield relative to holding the saving in a non-interest bearing deposit (or a lower yielding financial asset).

According to Eurostat, the average gross monthly wage in Greece for a single person with no children was 1,262.05 euros. Even at the current 10-year Greek bond yield rates (trading in the open market), each average household would have to buy a signicant (huge) volume of bonds to earn that sort of income flow per month.

Do your own arithmetic, the scenario doesn’t bear scrutiny.

Extremely rich Greeks might have the wherewithall to buy bonds in those sorts of volumes but then they are hardly going to dent the labour supply should they ‘stop working’.

Growth, by definition, has to be engendered by more spending. That is definitional. What Phelps is opposed to is more government spending because he has devoted his career to inventing bizarre explanations in an attempt to deny that the economy responds to government spending in a similar manner to increases in private spending.

If there is idle capacity, then firms respond to the increased sales by putting on workers and increasing output.

Earlier this year (February 9, 2015), the OECD released its latest – Economic Policy Reforms 2015

Going for Growth – publication.

If you don’t have a subscription to the OECD library, you can read the document on-line – HERE.

This is the annual report from the OECD ” highlighting developments in structural policies in OECD countries” and aims to provide “internationally comparable indicators that enable countries to assess their economic performance and structural policies in a wide range of areas”.

The framework they use is extremely biased to their neo-liberal thinking, which is not all inconsistent from the sort of extremist economics that Phelps propagates.

The OECD assemble a “responsiveness rate” indicator, which “measures the share of total policy recommendations on which governments in each country have taken some action.”

These are the “Going for Growth recommendations” proposed by the OECD and cover various so-called structural and financial reforms (including austerity).

A value of 1 means “significant” action has been taken, a value of zero means the opposite.

Greece stands out as having the highest “responsiveness rates” in both 2011-12 and 2013-14 – way ahead of the nearest nations which include Portugal, Ireland and Estonia.

The OECD average in 2013-14 was just over 0.3, whereas Greece recorded a value of 0.7. The EU average was around 0.5.

The point is that there has been massive changes within Greece over the post-crisis period, which are associated with public sector cutbacks, pension cuts, and regulatory changes – all part of the austerity story.

Conclusion

Edmund Phelps won the Nobel Prize in Economics (which is not a real Nobel Prize) in 2006, which I suppose means we should not be surprised by the rubbish that he dished up in this Op Ed.

Given the facts it is hard to take the following summation by Phelps seriously:

These findings weigh heavily against the hypothesis that “austerity” has brought Greece to its present plight. They indicate that Greece’s turn away from the high spending of 2008-2013 is not to blame for today’s mass unemployment.

We are now in a phase of “Austerity denial”, where conservatives attempt to massage history to avoid the unpalatable conclusion that the massive austerity that has been imposed on certain countries by the IMF and its partners in crime (in Greece’s case the European Commission and the ECB) has caused huge declines in GDP (levels and growth rates) and deliberately led to millions of people becoming jobless with associated rises in poverty rates.

That causality is undeniable.

It is as undeniable as climate change and should I add the Holocaust.

Advertising: Special Discount available for my book to my blog readers

My new book – Eurozone Dystopia – Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – is now published by Edward Elgar UK and available for sale.

I am able to offer a Special 35 per cent discount to readers to reduce the price of the Hard Back version of the book.

Please go to the – Elgar on-line shop and use the Discount Code VIP35.

Some relevant links to further information and availability:

- Edward Elgar Catalogue Page

- Chapter 1 – for free.

- Hard Back format.

- eBook format.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well said Bill. The only way out for Greece is to leave the Euro, dont pay the debts, back to drachma. Go to Russia and China for temp help and go between so they can trade with the west. That will shake usa imf and nato up and get some rationale into the subject

Deficitphobics and Austerity Deniers.

A lovely bunch.

“The Eurozone also experienced the little spike to 4 per cent in 2008 just before the crisis hit.”

Oil.

I just don’t get the German etc narrative. They implemented “export led growth” and then complain about other nations running trade and budget deficits. Put two and two together.

Any denial of austerity would also be a denial of inequality because you would have to assume the private stocks of money are well distributed before you could say something like unemployment results from a preference for leisure, and they are not. There is no leisure without a stock of money, in fact there isn’t even life without money. The unemployed are unemployed because they want jobs that don’t exist, and that’s by definition.

Columbia U appears to harbor a number of people like Phelps. Though perhaps few who lie as egregiously as he does. Can’t understand why he received the Swedish Bank prize. Then again, maybe I can.

The likes of Phelps are driven by ideology. That is, preconceived notions of how certain things should look and behave. They are either blind to reality or will try to bend it to suit their preconceptions. It is a common human disease and occurs across the spectrum of thought and behaviour.

The sufferers have failed Coping With Life 101 – Deal with reality before it deals with you.

A comment on the OECD scale. I think their binary scale is inadequate to account for the possible consequences of actions taken. I think it would have been better to have +1 for significant positive action, i.e., action that leads to improvement, however that is defined; 0 for doing nothing; and -1 for action that leads to significantly negative outcomes. As they have it, we seem to have be forced to view 0 as either doing nothing or doing something insignificant. Of course, there seems to be no difference between doing something insignificant and doing nothing. However, there would seem to a world of difference between doing something significantly positive and doing something significantly negative. But they are scaling them the same. All they seem to be interested in is whether the action taken had a significant outcome, whether positive or negative. How can this ‘significantly’ assist decision-making?

The report is 344 pages long and I found it difficult to find the scale you mention they are using. If it is anything like you describe, which I don’t doubt, it doesn’t seem useful to me. My modification is crude enough, but theirs seems to be patently inapplicable to any situation that does not differ from the trivial. I may be doing them in injustice, but I don’t see how.

Not everyone from Columbia was a dud. Vickrey and Okun for example would not have followed Phelps’ line of thought too closely on these issues.

The very definition of unemployment is those who are actively seeking work but unable to secure it. Voluntary unemployment means being out of the unemployment figures altogether, as you were preferencing leisure and not looking for work. You’d be out of the labour force participation figures.

Phelps’ island analogy doesn’t describe voluntary unemployment. It describes climbing the job ladder. You have the option of working for your current wage, or seeking a better one. I still cannot understand how the idea of unemployment being voluntary carries any weight. It simply doesn’t accord with any observable experience, goes against what a rational individual would think, and doesn’t even include jargon or complicated concepts to hide its true nature.

Here’s my take from August 9. REad the comments, especially the one by Frances Coppola. https://rwer.wordpress.com/2015/08/09/edmund-s-phelps-nobel-laurate-in-economics-stumbles-and-falls-when-assessing-the-dire-causes-and-dire-consequences-of-austerity-in-greece/

For someone who has never been interested in, or studied, economics – micro or macro – I was introduced to the discussion on MMT via a UTube interview with Bill MItchell. I was fascinated. I have been studying it ever since, not only the famous billyblog, but other advocates of MMT also. If we, and several other nations, are sovereign monetary nations, why are we – and they – ‘borrowing’ from abroad instead of printing their own money to finance ‘in house’ expenses, like infrastructure, education, health, etc. etc.? According to my understanding (which is limited), if we used our own money to buy real goods and services within our own economy, we do not incur debt which means there is nothing to pay back. It is only if we start ‘gambling’ with it on the international market that we can run into problems. Is this right, or am I totally misunderstanding the entire concept?

Another thing I could never understand; why America bailed out the big banks instead of the people they had exploited? I would have bought the debts (mortgages – domestic and commercial) from the banks, allowed the mortgagees to remain in their homes and businesses while paying a nominal rate to the government (similar to subsidised housing rents for welfare recipients) until such time as the economy was stabilised/resurrected and they could resume paying their pre-recession mortgage rates, either by re-financing, or continuing with the government as financier (I don’t know enough about economics to know which would be the best way to go; probably re-financing and paying the government back!). It seems to me that everybody would have been a winner; the banks would have been ‘saved’, homes and businesses would have remained populated and viable – instead of being abandoned and destroyed, and the massive destructive ripple effect on people and businesses (mass unemployment resulting in family breakdowns, suicides, massive stress on the health care system – such as it exists in the US, loss of infrastructure – whole towns and areas within cities falling into disrepair and decay) and so on would have been totally avoided. By just bailing out the banks, they now assume they are ‘too big to fail’ and are continuing doing what they did before, with impunity, and the public they are there to serve is paying the price for their deliberate exploitation of public funds and services. And the government got nothing back for its investment other than massive debt!

Am I wrong? Is this too simple a solution?