Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – November 14, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The central bank sets the short-run interest rate, and its associated liquidity management functions puts a limit of the rate it can pay on excess reserves held by the commercial banks..

The answer is True.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provide enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system would grind to a halt and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and the banks’ own desires.

Now the question asks whether the central bank can set the short-term interest rate and the answer is clearly yes. The question also asks whether it can set whatever penalty rate that it charges for providing reserves to the banks that it likes. The answer is no because the target rate (the short-term policy rate and the support or penalty rate are closely linked – the former constraining the latter).

The wider the spread between these rates the more difficult it becomes for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target (policy) rate.

Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.

So if the central bank really wanted to put the screws on commercial bank lending via increasing the penalty rate, it would have to be prepared to lift its target rate in close correspondence. In other words, its monetary policy stance becomes beholden to the discount window settings.

The best answer was True because the central bank cannot operate with wide divergences between the penalty rate and the target rate and it is likely that the former would have to rise significantly to choke private bank credit creation.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

- US federal reserve governor is part of the problem

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

Aggregate demand is the sum of all spending components (consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports). In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, we know that flows during a period add to relevant stocks. For example, if the flow of consumption spending rose by $200 billion in total in any one year, then if nothing else changes the stock of aggregate demand would rise by the same amount in the first instance (before the multiplier starts to work).

The answer is False.

Spending definitely equals income but that is not the point of the question, which is, in fact, a very easy test of the difference between flows and stocks.

All expenditure aggregates – such as government spending and investment spending are flows. They add up to total expenditure or aggregate demand which is also a flow rather than a stock. Aggregate demand (a flow) in any period and it jointly determines the flow of income and output in the same period (that is, GDP) (in partnership with aggregate supply).

So while flows can add to stock – for example, the flow of saving adds to wealth or the flow of investment adds to the stock of capital – flows can also be added together to form a “larger” flow.

For example, if you wanted to work out annual GDP from the quarterly national accounts you would sum the individual quarterly observations for the 12-month period of interest. Conversely, employment is a stock so if you wanted to create an annual employment time series you would average the individual quarterly observations for the 12-month period of interest.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

If the nation is running a current account deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and the government runs a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP, then we know that at the current level of GDP, the private domestic sector is not saving overall.

The answer is True.

Note the question did not ask whether the private domestic sector was saving per se. It specifically used the term saving overall, to mean the balance between total income and total spending. The private domestic sector might be spending more than its income overall, yet there could still be positive savings in the household sector which chose to consume less than its disposable income.

First, you need to understand what the aggregates mean. The statement that a government deficit (surplus) is equal to a non-government surplus (deficit) is correct to the last cent because is merely an accounting statement reflecting the way in which the national accounts are derived.

In other words, is true by definition. However, that statement tells you nothing as it stands about what, say, households are doing with respect to the use of disposable income.

Macroeconomics is the study of behaviour and outcomes at the aggregate level, and in that sense, blurs a lot of detail about what is happening below the aggregate level.

The point? It is sometimes useful to decompose the non-government sector into the private domestic sector and the external sector.

In turn, the private domestic sector is typically disaggregated in macroeconomics textbooks into the household and firm sub-sectors. From behavioural perspective, households consume and save (these are flows) while business firms produce and invest (also flows).

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

It is clear that if we had a balanced fiscal position (G = T) and an external balance (X = M) then (S – I) = 0.

Does this mean that there is a zero flow of saving in the economy? Definitely not. Households could still be consuming less than their disposable income which means that S > 0. What it means is that the private domestic sector overall is not saving because it is spending as much as it earns.

Clearly, if households do not consume all their disposable income each period then they are generating a flow of saving. This is quite a different concept to the notion of the private domestic sector (which is the sum of households and firms) saving overall. The latter concept (saving overall) refers to whether the private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning, rather than just the household sector as part of that aggregate.

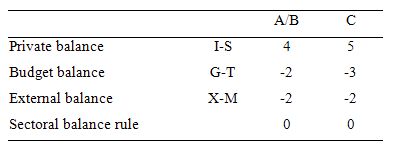

The following Table represents three options in percent of GDP terms. To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

The first two possibilities we might call A and B:

A: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earn

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

So Option A says the private domestic sector is saving overall, whereas Option B say the private domestic sector is dis-saving (and going into increasing indebtedness). These options are captured in the first column of the Table. So the arithmetic example depicts an external sector deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and an offsetting fiscal surplus of 2 per cent of GDP.

You can see that the private sector balance is positive (that is, the sector is spending more than they are earning – Investment is greater than Saving – and has to be equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

Given that the only proposition that can be true is:

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

Column 2 in the Table captures Option C:

C: A nation can run a current account deficit with a government sector surplus that is larger, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

So the current account deficit is equal to 2 per cent of GDP while the surplus is now larger at 3 per cent of GDP. You can see that the private domestic deficit rises to 5 per cent of GDP to satisfy the accounting rule that the balances sum to zero.

The Table data also shows the rule that the sectoral balances add to zero because they are an accounting identity is satisfied in both cases.

So what is the economic rationale for this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real costs and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

This Post Has 0 Comments