I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Listening to past Treasurers is a dangerous past-time

On January 23, 2016, a former Australian Treasurer Peter Costello (1996-2007) gave a speech to the Young Liberals (the youth movement of the conservative party in Australia) – Balanced Budgets as a Youth Policy – which was sad in the sense that some people never get over being dumped as out of touch and unpopular and was ridiculous in the sense that it is a denial of reality and macroeconomic understanding. He mounted the same old arguments that have been used to justify the pursuit of fiscal surpluses (grandchildren etc) but failed to recognise that his period as Treasurer was abnormal in terms of our history and left the nation exposed to the GFC as a result of the massive buildup in private sector debt over his period of tenure. The only reason he achieved the surpluses was because growth was driven by the household credit binge which ultimately proved to be unsustainable. Fiscal deficits are historically normal and should not be resisted. They are the mirror image in a national accounting sense of non-government surpluses, which historically, have proven to be the best basis for sustained growth and low unemployment.

Peter Costello was the Treasurer in the last conservative government which held office between 1996 and 2007. He aspired to be the Prime Minister to replace John Howard but he never had the numbers to depose the increasingly disliked Howard.

When the Liberals lost power in 2007, he declined to stand as Opposition leader and retired from Parliament. He never really had the heart to see his way through the Opposition years and instead we saw Tony Abbott take over the conservative leadership and become Prime Minister in 2013 (he has now been shown the door by his party).

While Costello was the Treasurer, the government ran fiscal surpluses in 10 of the 11 years is in office.

The biggest contractionary fiscal swing under his tenure occurred in the financial year 1999-2000 (a shift of 1.4 per cent of GDP).

A sharp slowdown in the economy followed that contraction and the fiscal balance was in deficit two years later (2001-02) – the only deficit that Conservative government recorded in the 11 years in office.

The Australian economy only returned to growth after that because the Communist Chinese government ran large fiscal deficits themselves as part of their urban and regional development strategy. That spurred demand in our mining sector.

Costello’s tenure also saw the reduction in net public debt as a per cent of GDP. In 2002, the federal government came under pressure from the big financial market institutions (particularly the Sydney Futures Exchange) to continue issuing public debt despite the government running increasing surpluses.

The reason: the public debt markets were becoming thin and the speculators wanted more pubic debt to use as safe havens and to price risk off.

At the time, the financial press which had been going on about the negative effects of fiscal deficits and public debt for years as part of the conservative smokescreen to downsize the public sector, didn’t bother to right about the irony and the contradiction of the situation.

According to all the logic that the government and these financial institutions had being continually pumping out was that the federal government was financially constrained and was forced to issue debt to “finance” its deficits.

By borrowing, the government allegedly forced up interest rates, which ‘crowded out’ robust private sector investment, to the detriment of the nation.

The debt allegedly also imposed severe financial burdens on future generations, which would further undermine future prosperity.

But, at the time, the Australian government was running increasing surpluses at this time and the logic would suggest that they should not be issuing debt at all!

Of-course, according to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), this logic is nonsensical. The national government, which is sovereign in its own currency, is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

Its deficit spending stimulates national income, which creates increased saving. Interest rates are decoupled from the fiscal position of the government by central bank operations and policy settings.

Public deficit spending, typically, ‘crowds in’ private sector investment spending.

But the debate at the time never questioned these aspects. Nor did it point out the irony of the private sector demanding the government issue more debt at a time when, even using its own flawed logic, it had no ‘financing requirement’.

The upshot was that an official Treasury enquiry was held (I submitted to that hearing). The result was that the industry demand for continued public debt-issuance even though the federal government was running increasing surpluses, the special pleading by an industry sector to lazy to develop its own low risk profit and too bloated on the guaranteed annuities forthcoming from the public debt, won the day.

Even though the federal government continued to run surpluses, it agreed to bow to the demands of the self-serving greedy hypocrites in the bond markets and continued to issue as much public debt that the industry desired.

It was a pathetic but mostly publicly-obscured aspect of Peter Costello’s reign as Treasurer.

Please read my blogs – Market participants need public debt and Doublethink and The problem of being a macro economist – for more discussion on this point.

And now, in his lecture to the Young Liberals the other had the temerity to claim:

… a generation can indulge at the expense of another. One of the easiest ways to do that is through deficit financing.

Anyone can spend money they don’t have if someone is prepared to lend to them. When governments do that the cost of the borrowing becomes a charge against future taxes. Future taxpayers have just that little bit less of their own taxes to pay for services because a component must go to service the cost of previous consumption. Maybe they will decide to send the cost on to the next generation and add in a little bit of their own overconsumption as well. Soon the debt and debt-servicing cost begins to accumulate. Soon future generations have less money to spend on their own needs because they are paying the cost of previous decisions. Their flexibility and their options begin to narrow …

One of the things I am proud of in my time in Government is that when the public, in its wisdom, voted us out we bequeathed no debt to future generations. Not only had the Government paid its own way, it is clear the debts of all the Governments that went before it. Never had the financial position of the Commonwealth Government been stronger.

Match that claim in the last paragraph with what I mentioned above for veracity.

But also familiarise yourself with the data provided by the Australian Treasury (AOFM division) – Table H13: Government securities on issue at 30 June 1983 to 2015.

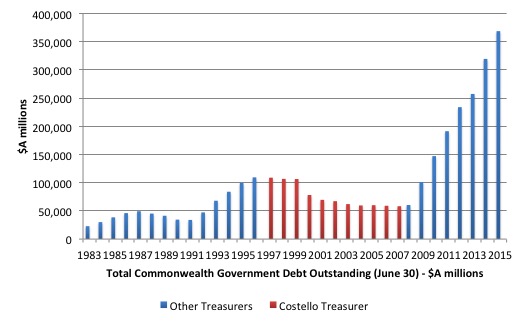

Table H13 shows the government securities on issue as at the June 30, 1983 to 2015. The following graph shows the total outstanding Commonwealth Government debt since 1983 in millions of AUD.

So while Costello is preaching to the young conservatives today, most of who were barely cogniscant when he was Treasurer, about his achievements, the facts are a little different. He was clearly ensuring that the financial markets had plenty of public debt – what about the burden on the grandchildren then?

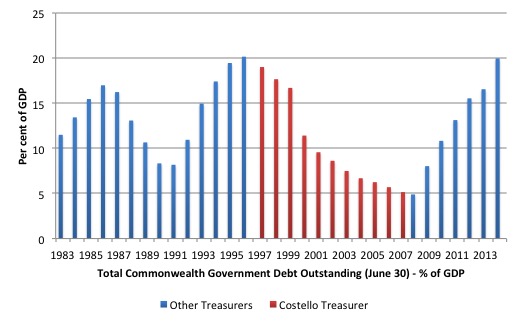

The second graph shows the same data as a percentage of nominal GDP. The story doesn’t change. The rise in the early 1980s was due to the severe recession in that period as was the case in the early 1990s. Again, the rise in 2009 was due to the Government’s stimulus package in the face of the impending threat of the GFC.

Australia was one of the few advanced nations that did not record an official recession during the GFC.

Of course, whether the public debt was lower or higher is not a matter of particular importance. The fact that the past Treasurer wants to misrepresent the data is one thing that reflects on his credibility, but in another sense, it doesn’t matter at all that he didn’t eliminate the outstanding public debt as he claimed above.

The main issue is the impoverished understanding of macroeconomics in the first paragraph of the past Treasurer’s quote (above).

It is clear that governments should always be forward looking and accept that its fiscal position will reflect changing challenges in terms of providing adequate public services and infrastructure while always be seeking to ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain production at the levels required to fully employ the available workforce.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, national government finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a ‘scorekeeping’ role.

MMT tells us that when a government boasts that a $x billion surplus, it is tantamount to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings recorded a decline of $x billion over the same period.

So when a government aims to achieve a surplus it must also be wanting the non-government $A financial asset savings to decline by an equal amount.

For nations that run current account deficits over the same period (such as Australia), we can then interpret that aim as saying that it is fiscally responsible to drive the private domestic sector (as a whole) into further indebtedness. That is a consequence of such behaviour. It is not what MMT would suggest is responsible fiscal management.

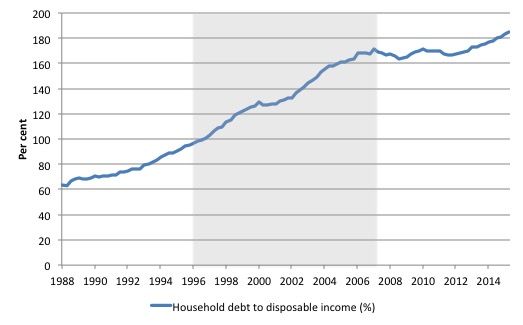

The following graph shows the recent history of Household debt to disposable income in Australia (per cent) since the September-quarter 1988 to the September-quarter 2015. The shaded area coincides with Costello’s period as Treasurer.

It was rising prior to Costello’s tenure as Treasurer but it accelerated under his watch as financial markets became increasingly intent on pushing as much credit as they could onto households. Part of this was due to real estate booms but also DIY consumption, boats, cars and all the rest of it.

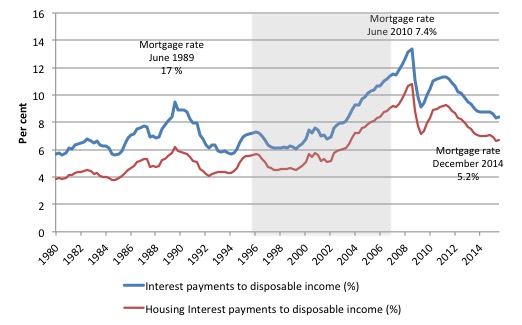

The next graph shows the interest burden on households as a result of the debt buildup with the shaded area coinciding with the period that Costello was Treasurer as before. Even though the interest rate was lower at the end of his tenure, the household debt burden was significantly higher as a result of the explosion of household debt.

So under Costello’s Treasurership, not only did the suppression of real wages growth continue and the gap with productivity growth widened further, but he also oversaw a dramatic shift in the level of precariousness in household balance sheets, which exposed the nation to turmoil in 2008, when the GFC hit.

He introduced a range of policies which also redistributed more real income to the top-end-of-town and undermined the conditions of the most disadvantaged.

But importantly, the only way he was able to run that many successive fiscal surpluses was because household consumption growth was maintained by the growth in credit and household debt. Somewhat later in his tenure the commodity price boom was also of assistance, which of course, had nothing to do with his acumen (not!) as Treasurer.

Moreover, when Costello assumed the role as Treasurer the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation measure was hovering around 15 per cent (unemployment at 8.4 per cent and 6.6 underemployment at per cent) and the economy was still recovering from the massive recession in the 1990s.

By the end of Costello’s tenure as Treasurer the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation measure was still at 10.8 per cent (with unemployment at 4.6 per cent and underemployment at 6.2 per cent).

He can hardly lay claim to having overseen a successful labour market strategy during his 11 years in office.

The crucial point is that the growth that occurred during his period of office was unsustainable because it relied on ever-increasing levels of household debt.

At present, there is a bias in the policy debate towards austerity manifested in fiscal strategies designed to push the fiscal balance into surplus.

Costello claimed in his speech to the Young Liberals that it was imperative that the government’s fiscal balance should return to surplus as soon as possible.

Why? Apparently:

1. It “will give us additional protection against financial instability”.

2. “we owe it to future generations”.

3. “getting the budget back to balance would put their Government in a stronger position on tax reform”.

But successive governments since Costello was Treasurer have largely adopted this fiscal bias. We can exclude the short period in 2008-09 when the federal government introduced a rather significant fiscal stimulus, which save the nation from recession.

The blowback from that highly responsible intervention from the Conservatives and their lackeys in the financial media put so much pressure on the government that by 2011 it was promising surpluses again, despite ongoing weakness in private spending.

The fiscal shift in 2012-13 under the Labor government (equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP) was much larger than any of the contractionary shifts that Costello engineered when he was Treasurer.

As predicted at the time, Australia’s growth rate fell sharply in the following year and forced the federal government into a 1.9 per cent of GDP fiscal expansion, largely driven by the automatic stabilisers (as tax revenue stalled and expenditure rose).

The fiscal balance moved from a deficit of $A18,834 million (1.2 per cent of GDP) in 2012-13 to $A48,456 million (3.1 per cent of GDP) in 2013-14.

The increase in the fiscal deficit was mostly due to the incompetence of the then Government in trying to pursue a fiscal surplus at a time when household expenditure on private investment expenditure was incapable of supporting sufficient real GDP growth and the external sector remained in deficit.

It demonstrated that the government cannot really determine the fiscal balance that results at the end of some period and if it attempts to reduce net public spending at a time when non-government spending is moderate it will almost always fail and the result is slower real GDP growth and rising unemployment.

That is exactly what is happened in the last few years.

It is clear that this strategy is failing because the attempts to reduce fiscal deficits are undermining economic growth, which, subsequently, undermines the growth in tax revenue that the governments projected would drive them back into surplus.

Moreover, this shifting behaviour in non-financial corporations coupled with the observation that household saving out of disposable income is once again rising, after the credit binge prior to that GFC, is redefining what we might consider to be normal.

Prior to the GFC, the private credit binge (largely driven by household borrowing) allowed economic growth to be elevated and in many countries the fiscal position to move towards smaller deficits or indeed, in some cases, into surplus.

While Costello was recording his 10 fiscal surpluses between 1996 and 2007 household debt ratios rose to record levels and economic growth was consistently around or above trend.

The household saving ratio over that period fell into negative territory. The household saving ratio has since returned to around 10 per cent of disposable income as households seek to reduce the precariousness of their balance sheet positions.

Even without the drag on aggregate demand from this shifting non-financial corporation lending behaviour, the reversal in household saving behaviour, meant that any strategy by government based upon returning to those fiscal surplus outcomes would be impossible to sustain.

The problem is that the government still attempted to reduce the deficit and economic growth has faltered since that time as a result of the slow growth in domestic spending.

The point is that the household credit binge is over and the government has to return to its normal position of fiscal deficit of varying magnitudes.

The shift in non-financial corporation lending behaviour only magnifies that fact. With households now returning to more normal levels of consumption growth, the slowdown in private investment behaviour has increased the spending gap that the government has to fill.

For a nation with a strong external position, as evidenced by current account surpluses, the necessity for government deficits to close private domestic spending gaps is reduced, if not, eliminated.

In Australia’s case, the external sector acts as a drain on overall demand (spending), which means that the government deficit is both normal and a required outcome of the saving behaviour of the private domestic sector.

As long as the government sector ‘finances’ that rising saving behaviour from the households and firms, economic growth can continue and the paradox of thrift effect thwarted.

The rising net spending promotes income and employment growth, which combine to generate the rising saving capacity desired by the households and firms.

In Australia’s case, the reality is that fiscal deficits have been the norm over successive economic cycles. There is no evidence that Australian governments have ever been able to succesfully ‘balance budgets’ over the cycle without negative consequences following.

The further evidence is that as the neo-liberal persuasion has become dominant in macroeconomic policy, Australian governments have attempted to run discretionary surpluses. The outcomes of this behaviour have not been good and overall this period (since around the mid-1970s) have been associated with lower average real GDP growth and more than double the average unemployment rate.

You can compile a reasonable dataset to explore this question spanning the period 1953-54 to the present day from two sources. The earlier data (1953-54 to 1970-71) is from the historical publication by R.A. Foster and S.E. Stewart (1991) Australian Economic Statistics, 1949-50 1989-90, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney.

The second time series (1970-71 to 2010-11) is from Statement 10 which is the data appendix to Budget Paper No. 1 published by the Commonwealth Government when it delivers its annual fiscal statement.

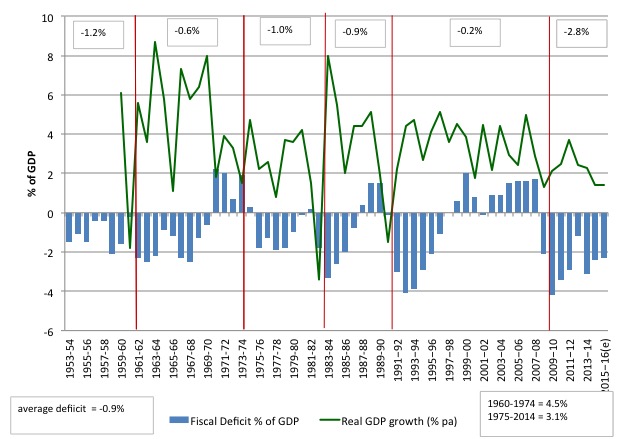

There are some issues about combining this data set and also with each individual data set. But in general the graph below is a reasonably reliable depiction to the history of Federal government fiscal outcomes outcomes over this period. The columns show the Federal fiscal balance as a per cent of GDP (negative denoting deficits) while the green line shows the average quarterly real GDP growth (averaged over the financial year at June).

The red vertical lines denote the trough of the respective business cycles. So the real GDP growth line approximates where in the year the negative real GDP growth manifested. But for our purposes it is near enough.

The upper numbers in boxes are the average deficits over each cyclical periods. The average deficit over the whole period was 0.8 per cent of GDP. The average real GDP growth per quarter from 1959-60 was 1.2 per cent and after 1975 this dropped to 0.8 per cent. The unemployment rate averaged below 2.0 per cent in the pre-1975 period and averaged around 5.5 per cent after 1975.

The 1975 Budget was a historical document because it was the first time the Federal Government began to articulate the neo-liberal argument that budget deficits should be avoided if possible and surpluses were the exemplar of fiscal responsibility.

Some points to note:

1. One the rare occasions the budget was pushed into surplus (usually by discretionary intent of the Government) a major recession followed soon after. The association is not coincidental and reflects the cumulative impact of the fiscal drag (that is, the surpluses draining private purchasing power) interacting with collapsing private spending.

2. There is no notion over this period that the budget outcome was “balanced” over the business cycle. The historical reality is that the federal government is usually in deficit. If I had have assembled more historical data which is available in the individual budget papers going back to the 1930s then it would have just reinforced the reality that surpluses have been rare in our history independent of the monetary system operating (the old convertible system or today’s non-convertible system).

3. The Australian federal government ran fiscal deficits of varying sizes in 75 per cent of the years between 1953-54 and 2015-16 (44 out of the 63 years).

4. The fact that the conservatives were able to run surpluses for 10 out of 11 consecutive years (1996 to 2007) is often held out as a practical demonstration of how a disciplined government can run down public debt and provide scope for private activity. The reality is that during this period we have witnessed a record build-up in private indebtedness (see below).

The only way the economy was able to grow relatively strongly during this period was that private spending financed by increasing credit growth was strong. This growth strategy was never going to be sustainable and the financial crisis was the manifestation of that credit binge exploding and bringing the real economy down with it.

5. The higher deficits in the recent period is testament to the fiscal stimulus package and, perversely, the fiscal contraction that followed. Remember this is a ratio of the fiscal balance to GDP. So if the numerator (fiscal balance) goes up faster than the denominator (GDP) then the ratio rises and vice-versa. But if the denominator falls more quickly than the numerator (at a time of fiscal austerity) the ratio can also rise. The previous government cut hard in their second last fiscal statement and that caused the economy to slow.

It is clearly preferable that households be supported by fiscal policy to return their balance sheets back into safe waters. That will require governments returning to their ‘normal’ role – running budget deficits.

That is the ‘ongoing credit excess’ in the private domestic sector has to be reversed and that will require public net spending support.

There is no ‘growing fiscal burden’ in Australia. It might be that the political process will endorse a larger share of public resource usage over time as the population ages and health care provision needs increases.

The net burden of that trend will be the sum of the resources deployed in the health and aged care industries minus the resources freed from other areas (like primary school education, child health centres).

It follows that the entire logic underpinning the ‘fiscal deficits burden our kids’ claim is flawed. Financial commentators often suggest that fiscal surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly ‘stored away’ will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the neo-liberal misconception.

This is redolent in Costello’s spurious claim that surpluses will help the Australian government cope with the next financial crisis.

The standard government intertemporal budget constraint analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is ridiculous. The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a ‘bridge’ that spans the generations in some restrictive manner. Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures. Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain.

Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

Conclusion

When MMT proponents argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit.

We are not advocating unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that the economy achieves full employment. Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light.

The nation does need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run fiscal surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

In terms of the challenges presented by rising dependency ratio, the obsession with fiscal surpluses will actually undermine the future productivity and future provision of real goods and services.

The quality of the future workforce will be a major influence on whether our real standard of living (in material terms) can continue to grow in the face of rising dependency ratios.

Governments should be doing everything that is possible to educate, train and employ our youth so that they will achieve higher levels of productivity into the future and offset the inevitable rises in the dependency ratio.

By pursuing a fiscal surplus when there is clearly significant excess productive capacity in Australia and when the private domestic sector is highly indebted the government is not only damaging the present but also undermining the future.

Maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is madness to exclude our youth – many of whom will enter adult life having never worked and having never gained any productive skills or experience.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that the economy achieves full employment.”

The line I’ve been taking recently is that you only tax when you need to free up real resources that are currently been used elsewhere. Resources that are now needed for the public purposes – as determined by the democratic vote.

That means you can target the taxation, or you can use other measures available to free up those resources (such as limiting bank lending, or planning restrictions).

Costello is just another ex Tory Party minister who can’t retire gracefully. Biff (Mark Latham,ex leader of the Tory Lite Party in opposition) coined an expression in his inimitable fashion – ” Just a conga line of suckholes”.

Pot – Kettle ?

I find it particularly amusing when Costello says he paid off debt, had money in the bank and established the Future Fund. An examination of the asset side of the government’s balance sheet through time reveals that so-called net debt was eliminated via accumulating surpluses in deposits at the central bank. The amusing thing is that the same 60 odd billion gets counted three times: (1) surpluses were indeed accumulated in deposits (‘money in the bank’); (2) in NET terms debt was ‘paid off’ only in the sense that these deposits exceeded gross debt on issue; (3) much of these deposits were transferred to the Future Fund as its seed capital, along with some Telstra shares. Given the terms of trade boom sponsored by the Chinese was largely squandered on middle class welfare rather than seen as the temporary windfall it so clearly was and socked away, is it any wonder that Costello needs to imply he had $180 billion to show for it instead of $60 billion (plus a whole bunch of inflationary pressure in 2006-7)?!

If budget surpluses by the monetary sovereign do not result in deflation because exports compensate for the purchasing power destruction then aren’t foreign importers being granted increased purchasing power at the expense of less purchasing power for the domestic population?

So Australia is giving away resources to pay down sovereign debt that isn’t a problem in the first place except for paying positive interest?

Btw, aren’t interest on reserves (IOR) and interest paying sovereign debt supposedly required to prevent the overnight inter-bank lending rate from going to zero*? But please note that the commercial banks are gifted with the huge amount of reserves created by sovereign spending simply because there is no other way to credit individual, business, and other accounts since, except for commercial banks, no one else in the private sector is allowed to have accounts at the central bank? What if sovereign spending was credited by default to individual, business, etc accounts (if they were allowed) at the central bank? Would reserves be so cheap to borrow then? Not likely, since some of those reserves would effectively be locked away by the liquidity needs and risk-free saving preference of individual, business, etc accounts at the central bank.

*Btw, how is this a problem anyway?

Oops! The above comment isn’t relevant to the current article. My apologies.

Well, actually it is relevant. Sorry.

With regard to “budget outcome …. “balanced” over the business cycle.”

Orthodox economists use this phrase as a fetish statement but also as a “dog-whistle falsehood”. The general public would regard this phrase as meaning that deficits and surpluses are arithmetically balanced over the budget cycle. And this is what the public are meant to understand; that the government is not “printing money” over the cycle or many cycles. If you pin down orthodox economists by pointing out that under conditions of growth the money supply must grow to simply maintain parity they basically reply as follows. “Well yes, everybody (meaning economists and politicians) understands that the money supply must grow if the economy grows. So “balanced over the business cycle” means a net deficit to allow the money supply to grow just proportionally.” This is the essence of the answer if you can actually get an honest answer out of an orthodox economist.

Why do I call it a “dog-whistle falsehood”? I do so because it is strictly a falsehood if interpreted literally and the public are meant to interpret it literally and to believe it. At the same time orthodox economists and neocon politicians are dog-whistling to each other. They know their statements are not literally true in the sense the non-economist public will take them. But it is a handy way to couch matters to obscure real financial relations and keep the public ignorant of the real power of the money system. This system’s powers must only be used to enrich the elite. Only the elite can be permitted to get something for nothing. Ordinary people must support and subsidise their own exploitation and oppression.

There were two big problems with Costello’s surpluses. Firstly they were achieved partly by resorting to false economies (like underinvestment in infrastructure, and selling off Sydney Airport for a fraction of what it was really worth). Secondly, they weren’t big enough! The tax cuts after 2004 meant the RBA had to hike interest rates a few times.

It is sensible to run surpluses during the boom. It does not matter that increasing private indebtedness is not sustainable. The government can easily deal with any crash if and when it occurs.

@aka, sovereign debt means foreign currency debt. Am I right in thinking that wasn’t what you were asking about?

Exporting more means the currency value will rise, resulting in more purchasing power which will help counteract inflation.

When a government takes more money out of the economy, it enables the private sector to put more in without it resulting in more inflation.

@ Neil,

“The line I’ve been taking recently …..”

But will the average person agree with or even understand the line you are taking? I think I know what you are getting at but I’m not sure I agree with it. But, I’d just make the point that it doesn’t really matter what line any of us might be taking if we have no power to change anything and aren’t part of a wider political organisation which has a chance of attaining some sort of power. That means talking to real people.

So, unless we are professional economists, if we are taking any sort of line at all, it has to be aimed at the understanding of where people are now and not where we would like them to be, or where they might well be at some time in the future.

The only way, IMO, to explain the relationship between the govt’s budget deficit, the trade deficit, and the level of private borrowing, to the next person you might randomly bump into in the street, is to say something like that if any country like Australia or the UK, has a trading imbalance with the rest of the world then someone, either Govt and/or everyone else in that country, has to fund that deficit by borrowing. MMT purists will balk at the word ‘borrowing’ but we have to make the occasional compromise.

Just occasionally the level of ‘everyone else’s’ borrowing is very high, even too high, which enables (if that is the right word) the Govt to run a surplus at the same time as the trading balance is in deficit. This was with case with the Blair/Brown surpluses in the UK around the turn of the millennium and with Costello’s surpluses before the GFC.

Maybe you’ve had a different experience to me and the guy-in-the-pub might know what you are talking about when you tell him that we only ” only tax when (we) need to free up real resources” – but I doubt it. He’ll probably understand if we say, and carefully explain why, we only need to tax to prevent high inflation though!

@Aidan Stanger,

Actually I did mean sovereign debt though I erred to say that the monetary sovereign pays down sovereign debt since non-interest paying fiat is just another form of sovereign debt – one that pays zero interest. Indeed, all sovereign debt should pay at most 0% interest otherwise we are providing welfare proportional to wealth and not proportional to need.

Peter, I think it is pretty simple. Let’s take schools. If you want to free up construction workers ban casinos until schools get built. If you want to free up teachers tax private schools. Just tax or ban the thing you need to free up.

“is to say something like that if any country like Australia or the UK, has a trading imbalance with the rest of the world then someone, either Govt and/or everyone else in that country, has to fund that deficit by borrowing.”

Foreigners are saving in currency, then swap it to a higher interest account. No need for govt to offer a higher interest account. Why pay corporate welfare when there is no need.

Bob,

Yes I know it is all pretty simple in our imaginary economy. We can do whatever we like there. I’m concerned we should move out and into the real economy.

In reality, we can’t just ban casinos or ban private schools or even impose a tax on private schools just to free up teachers. MMT enthusiasts have absolutely no power to do anything like that. It’s not even a problem right now, anyway, if we need more teachers for the State system we can have them simply by creating more teaching posts. There plenty of qualified teachers who are doing other things or not even working at all. They may not even be counted as unemployed if their partners are working.

Yes, of course, I do understand that the government deficit is dependent of the desire of the non government sector to save. I also agree we shouldn’t be paying corporate welfare. If we didn’t there would be less desire to save anyway and that would reduce the govt’s deficit.

So why don’t we just say this? We can fill in the other details later once we have the people who we need to be listening to us actually doing that.

The Curious thing about the GFC in the US (and the UK) is that the Gov fiscal position was Deficit.So the private sector would of been in surplus and yet it still managed to collapse.

According to FRED data the housing delinquency rate took of after Q4 2007 just as Mortage debt service payments as percentage of income began too peak at 7.19 ,when it had been hovering at around 5.5-6 % for the preceding 20 years.

I still don’t understand why defaults took off if the Gov fiscal position was in deficit.Although interestingly in went from -3 to -1% in 2007.

BUT how come households were increasingly struggling to pay mortages off and as a result going into default,when the private sector was in fact in surplus,and unemployment didnt really take off after spring 2008.

The resetting of Adjustable rates are apparently not the answer,as according to a paper (working paper 18082 from the NBER) they had no discernible affect on the quantity of defaults.

Equally why did these defaults (07)which saw the collapse of REIT’s necessarily translate into the collapse of private spending which presumably explains the huge increase in Unemployment in spring 2008.(which also precludes rising unemployment as an explanation for increased defaults in 2007).

According to a Yale online module the loss of private spending was in part created by the run on ABCP funds (Asset Backed Commercial Paper) which financed credit cards,auto loans and student debt,the withdrawl of this funding for consumer credit would of obviously put a dent on consumer spending.Apparently it had been awash with funds from the Global saving glut in the build up to the GFC.

?

@ Jake,

The private (domestic) sector isn’t the same as the non-government sector. The US PDS was in deficit in the lead up to the GFC. Not in the UK though – even though the surplus of the PDS was small at the time.

Incidentally, the PDS for the UK is now in deficit but not for the US.

You have to take into account the foreign sector too.

I am in agreement with Petermartin2001. We just talk about need for government deficits to allow private sector saving. For this, we only need to use the sectoral balances, which no one can dispute, because it is just arithmetic.

Indeed, most people can understand it, if they are prepared to spend about 15 minutes thinking it through. Then, the more “controversial” aspects of MMT do not enter the picture at all, but the spurious neo-liberal demand for government surpluses is exposed.

Right, so just looked up Current account balance

It troughed at a deficit of -6% of gdp at 2005 and went back up to -2% briefly by 2009.At the key Time of late 2007 it was at -4%.

Which means;

Fiscal deficit of -1%

Current account balance of-4%

So the domestic balance would have been -3%.

Podargus

It should read Peter “Boof” Costello and Mark “Lard-ass” Latham aka “Biff the bovver boy.” And yep they both ought get off the stage before the crowd starts pelting them with rotten eggs.

Should that not be passtime, Bill? As opposed to past-time.

Or have I missed a pun somewhere?

If the actual saving of the double digit worlds wealthiest who own half the worlds

wealth is anything to go by ( they are humans too) then the desired saving of the

non government sector is unlimited.

Most of us could benefit with a lot more savings ,for large expensive items,for times

when our income earning abilities decline.I suspect the vast majority of people’s well

being would be significantly increased if there was greater savings in the non

government sector that is significantly larger international government sector deficits,

BUT satisfying people’s DESIRE for savings that is an insatiable abyss.