This is the second part of my thoughts on the current acceleration in military spending…

The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party

This blog provides another excerpt in the unfolding story about Britain and the IMF and the Monetarist sell-out by the British Labour Party once it was reelected in February 1974. As I noted in this blog – The British Monetarist infestation – I am currently working to pin down the historical turning points, which allowed neo-liberalism to take a dominant position in the policy debate. In doing so, I want to demonstrate why the ‘Social Democrat’ or ‘Left’ political parties, who still have pretentions to representing the progressive position (but have, in fact, become ‘austerity-lite’ merchants), were wrong to surrender to the neo-liberal macroeconomic Groupthink. This is a further instalment of my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. Today, we trace the tensions within the Tory Party during the period 1970 to 1974, when the old school “One National Conservatism” represented by Edward Heath came into conflict with the growing Tory Monetarists, who would eventually be the bulwark of Margaret Thatcher’s pernicious regime later in the 1970s.

The Tory Party struggles with Monetarism 1970

As the Conservatives were formulating their election strategy for the June 1970 general election it appeared that they were preparing to implement a Milton Friedmanesque Monetarist agenda – to reduce inflation and bring the unemployment down to what Friedman had termed the ‘natural rate’, which was no more than some rate at which inflation was stable, although the Monetarists had convinced economists that this was the true full employment unemployment rate.

The Shadow Cabinet held a planning meeting over the weekend January 31-February 1, 1970 at the famous Selsdon Park Hotel in Surrey. In his memoirs, Edward Heath said the meeting was “to co-ordinate the results of our policy reviews and discuss an early draft of our manifesto” (see Heath, E. (1988) The Course of My Life: The Autobiography of Edward Heath, London, Bloomsbury Reader.)

The meeting would confront Heath’s so-called One Nation Conservatism (‘Tory Democracy’) with the emerging right-wing Monetarism that had infested the British finanacial economists and many technocrats in the bureaucracy.

One Nation Conservatism had its roots back with Benjamin Disraeli, who sought to attract the working class vote by advancing a culture where the societal elites had a responsibility to help those below them on the social and income scale.

While not an apology for a sharply hierarchical society, the concept of Noblesse oblige was well founded in the Post World War 2 Tory Party and was in sharp contrast to the emerging right-wing Monetarism that would, by the time Margaret Thatcher had become Conservative leader, subsume the Conservative Party.

Critically, the ‘One National Conservatism’ was pragmatic and allowed Tory governments to embrace what they saw as ‘Keynesian’ interventionist economic policies if the non-government sector was struggling and unemployment was rising.

The right-wing Monetarists hated this type of intervention and advocated free market policies where the ‘price mechanism’ would sort out unemployment and inflation, along the lines espoused by Milton Friedman.

The Selson Park meeting debated the Ridley Report on nationalised industries and a leaked document (Memo by B. Sewill) showed how far the Tory Monetarists wanted to push the Party down the free market track.

[References:

1. Report of the Policy Group on Nationalised Industries, chaired by N. Ridley, July 11, 1968, CPA ACP(68)51, CRD/3/17/12

2. ‘Publication of Policy during 1970’, memo by B. Sewill, 21 January 1970 for Shadow Cabinet weekend, January 31-February 1, 1970, Selsdon Park Hotel, CPA Selsdon Park (SP/70/12 LCC Papers).]

As it turned out the mainstream Tory position was maintained. Even a proposal to water down the National Health System was rejected because it was determined that the changes would have damaged the working class (see Selsdon Meeting Transcript (afternoon session), January 31, 1970).

The public perception of the meeting was different to the reality thanks to some sensationalist journalism from Fleet Street, which exploited a statement from the Shadow Chancellor, to suggest the Tory’s were now shifting to the right and had become Monetarists.

It is true that the Party did advocate tax and public spending cuts and the abandonment of wage controls as a way of differentiating themselves from Harold Wilson’s government. Urged on by right-wing MP Nicholas RIdley, the Party also eschewed any further nationalisation.

But the reality that followed Heath’s election was very different. Far from adopting a Monetarist stance, Heath performed his famous ‘U-turn’ when the quintessential British company Rolls Royce was on the brink of insolvency. Heath partly nationalised the company and injected public funds to keep it alive. Similar public spending injections helped rescue the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders.

With unemployment rising, the Tory’s introduced the ‘Dash for Growth’ in 1972 and 1973, which precipitated the short-term ‘Barber Boom’. These fiscal interventions were the anathema of what the right-wing Monetarists in the Party wanted. In a way, this period hardened the resolve of the right-wingers to take over the Conservative party.

As a matter of history, the U-turn spawned a harsh reaction by Tory right-wingers led by Nicholas Ridley, who formed what has become known as the Selsdon Group in 1973. This free-market lobby group would lay out the agenda for Margaret Thatcher and John Major after her.

Heath was also battling with the trade unions, a traditional Tory battlefield and his government lost political credibility through their ham-fisted attempts to imprison union leaders under the newly legislated Industrial Relations Act 1971.

A protracted mining strike, forced the government to implement the Three-Day Week in early 1974 as a way of conserving coal stocks by limiting electricity usage.

The 1974 election was subsequently fought on industrial relations issues with the Tories using the mantra “Who Governs Britain” to garner electoral support. They failed because the public had largely been unimpressed with their handling of the industrial disputes.

It is clear that during this period (1971-73) the Tory Party was splitting internally. Right-wing MPs such as Keith Joseph, who became a major influence on Margaret Thatcher (for example, influential in the establishment of the free market think tank, the Centre for Policy Studies in 1974, when Heath lost office).

Joseph was seen as a likely successor to Heath but his extreme social views (for example, supporting controls on the number of children poor people could have) undermined his attempt.

Joseph had become enamoured with the Monetarist ideas of Milton Friedman and in May 1970 published a paper on inflation, which captured the sharp shock idea that Friedman espoused as the best cure for inflation.

Joseph said that:

… consistent policies – involving some unemployment, some bankruptcies and very tight control of public spending – will be needed for at least five years (see Denham and Garnett, 2014: 245).

Joseph was making the transition into full blown Monetarism in that he wanted the Bank of England to control the money supply but still realised that “Deceleration of the money supply should be very gradual if unacceptable levels of unemployment are to be avoided” (Denham and Garnett, 2014: 245).

He also realised that inflation could be driven by supply factors such as wage push or margin push, which also set him apart from the Friedman purists at the time.

In their biography on Joseph, Andrew Denham and Mark Garnett (2014: 245) suggest that Heath was resistant to the Monetarist push within the Tory Party because he:

… was a Keynesian by instinct and by intellectual conviction.

[Reference: Denham, A. and Garnett, M. (2014) Keith Joseph, London, Routledge.]

They also report that (p.245):

In the early days of his government Heath had held a private discussion with Milton Friedman, and found the latter wholly unconvincing …

Heath, himself reflected on the tensions within the Tory Party at the time in his autobiography. He wrote that the Monetarist push within the Party (Heath, 1988: 521) “failed to cut any ice with the great majority of his colleagues”.

Denham and Garnett note that the Tory Monetarists failed to understand that the basic conditions that would be required for Monetarism to be a viable explanation of the inflation process were absent. They recount a Tory Shadow Minister at the time saying that Joseph (p.246):

… brought two professors along. They knew even less than he did …

The belief that the velocity of circulation was constant, which then if there was truly full capacity production would mean that an increased money supply growth rate would generate higher inflation, was etched in the Tory Monetarists minds.

The problem was that the velocity was in decline at the time, and Denham and Garnett say that “To an objective observer this statistics ought to have dealt a fatal blow to the monetarist case, since it implied that inflation should have been falling” (p.246).

But Tories such as Joseph didn’t blink in the face of this damaging reality and blithely continued to advocated free market policy changes and tighter control by the Bank of England on the money supply.

It also seemed to escape him that the Bank was unable to control the money supply, a fact that became obvious in the next few years as the CCC policy was introduced and abandoned.

[Note: I considered the “Dash for Growth” in this blog – The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government. The narrative today is a little out of order but I realised there was some backfilling necessary to understand just how stupid the comments of Denis Healey in 1976 were about the self-evident truth of Monetarism]

Breakdown of Bretton Woods

The breakdown in the Bretton Woods system in August 1971 and the failed attempts under the so-called Smithsonian Agreement to revive it created major problems for governments around the world who were wedded to maintaining the fixed exchange rate system.

The British government resisted floating the pound for some months but on June 23, 1972, the Tory Chancellor Anthony Barber bowed to reality and sterling went free on international markets.

The necessity was driven by growing current account deficits and the drain on Bank of England foreign currency reserves, as it tried to defend the previous fixed parities.

With inflation at elevated levels in Britain and large wage settlements in the nationalised oal and railway sectors, speculative pressure on the pound became intolerable.

Floating not only freed up monetary policy, but it also eliminated the inevitable recourse to the IMF for funds to shore up the continual drain on foreign reserves.

The float remedy should be borne in mind when we consider the decision by Labour Party in 1976 to borrow from the IMF.

Further, it is interesting to note that when Barber announced his decision in the House of Commons, the Labour Party railed against the Tories claiming that “the decision to float was in direct contradiction of the Government’s agreement to keep the pound’s exchange rate within a narrow band as a first step towards economic and monetary union with the other Common Market countries” (Source).

It wasn’t the first time that the Labour Party had failed to understand how floating the currency restored the currency sovereignty of the nation and allowed the Government to concentrate on domestic policies rather than accept higher interest rate and lower public spending regimes designed to attract foreign capital inflow and suppress imports.

Both policy biases ensured a recession bias was constantly threatening under the fixed exchange rate system.

And then they had to deal with the oil crisis

By June 1971, the British inflation had hit 10.3 per cent and over the next few years it fell slightly back to around 6 per cent. For those who were prosecuting the Monetarist line, the data was not very supportive.

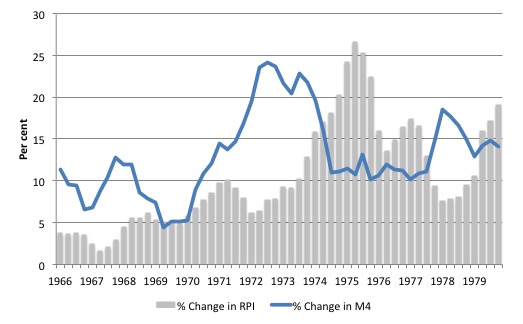

The following graph shows the annual inflation rate (Retail Price Index) and the annual growth in broad money (M4) in Britain between the March-quarter 1966 and the December-quarter 1979.

While the broad money supply accelerated in the period 1970 to its peak in the September-quarter 1972, the inflation rate did not keep accelerating and had subsided significantly as the rising unemployment rate suppressed demand conditions in the domestic economy.

The inflation rate really took off in late 1973 at a time when the growth in the broad money supply had more than halved.

This acceleration was caused by the OPEC oil crisis.

The outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East in October 1973 (the 1973 Arab Israeli or Yom Kippur War) was accompanied by the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

A few days later, on October 16, the Arab nations increased the price of oil by 17 per cent and indicated they would cut production by 25 per cent as part of a leveraged retaliation against the US President’s decision to provide arms to Israel.

The price of oil rose by around three times within eight months (US Energy Information Administration, 2013).

The BIS (1974: 30) assessed at the time that the US, “despite the embargo placed on it … was in a better situation than Europe or Japan to withstand both the internal and external effects of the OPEC countries’ actions owing to its lesser dependence on oil imports.”

The result, the US dollar appreciated by 17 per cent in the six months to February 1974, basically taking it back to the December 1971 value at the time of the signing of the Smithsonian Agreement.

Further, the European currencies including the British pound suffered major depreciation, as did the yen. Between July 1973 and October 1974, the pound depreciated by by 6 per cent against the US dollar. It continued to fall over the next few years, exacerbating the cost inflation that came with the OPEC oil price rises.

The OPEC oil price hikes in the 1970s provided the switch point that seemed to validate the Monetarist claims that excessive public spending would generate accelerating inflation. The ‘Dash for Growth’ was blamed.

The public only had a crude understanding of Monetarism, which prevented any meaningful technical debate cutting through the increasingly frantic media attention that the Monetarists were enjoying.

The high inflation that followed the OPEC oil price hikes was accompanied by high unemployment as governments tried to suppress economic activity to control the inflation.

British Cabinet documents from December 1973 show that the Chancellor was preparing a statement to accompany an emergency ‘budget’ in the same month, which described the OPEC impacts as the “gravest since the end of the war” ((Source).

It was clear that the British government was intent on diverting blame for the rising inflation away from itself. The Chancellor noted that “The first act, and the one over which this country has the least control, was the decision of the oil-producing and exporting states … to bring about by unilateral action an entirely new price regime for oil”.

He also said that the “subsequent decision of … oil producers … to reduce the supply of oil to the rest of the world to a level which is well below present requirements has created an entirely new situation”.

The upshot was that he predicted an “energy shortage in all oil-importing countries leading to stagnant, if not falling, output accompanied by rising unemployment”.

He secondly, singled out the traditional Tory scapegoat – “the industrial action in the coal and electricity industries, and on the railway” – for attention, once again to deflect blame for the rising inflation.

He blamed the trade unions for forcing the nation onto the Three-Day week.

The Government documents reveal that they were also concerned about the impact of increased oil imports (in value terms) on the already rising external deficit.

In that context, they formulated an action plan which would significantly cut public spending and increase taxes over the next 12 months.

They also introduced quantitative controls on credit access to choke off consumer demand and the Bank of England was “also taking steps to strengthen the techniques for controlling the growth of money and credit”.

The problems magnified when OPEC doubled the oil prices on December 23, 1973 and the mining union upped the ante on February 5, 1974 when they dropped the overtime ban in favour of a general strike

The Heath government lost office in February 1974 with the nation in a mess.

This era of stagflation provoked a major shift in economic thinking.

The Keynesian macroeconomic orthodoxy, that dominated the post World War II period, was predicated on the view that the total spending in the economy determined the level of unemployment.

Firms employed people if they had sales orders. After the cessation of the war and with the mass unemployment of the Great Depression of the 1930s still firmly etched in the minds of policy makers and the population, governments generally committed to using fiscal and monetary policy to maintain states of full employment where everybody who wanted a job could find one.

This led to an acceleration of prosperity across the advanced world.

Accompanying this approach was a view that inflation would only result if the spending outstripped the capacity of the firms to produce goods and services, leaving them no option but to increase prices.

Accordingly, high unemployment should be associated with low inflation and vice versa.

Stagflation thus presented a new situation.

Conclusion

… to be continued …

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

I will write a separate blog about this presently, but today we finally published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text – today (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 USD)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 USD)

It is retailing for at Amazon.com or £42.00 or €58.85 from Amazon Europe (UK).

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

Bill ~ You may be interested …

From Bloomberg: Ignored for Years, a Radical Economic Theory Is Gaining Converts

Bill,

This is a huge issue which has scorched itself onto the brains of the baby-boom generation. Would it be possible for you to discuss in more detail the effect of industrial relations, wage demands etc on prices? Also, perhaps discuss in hindsight what agreements could have been made between the government and trade unions.

Kind Regards

When I look at that graph I See a 3 year lag ?

Between M4 and inflation.

Is this possible or am I just seeing things ?

Dear Derek Henry (at 2016/03/16 at 9:19)

And what theoretical or behavioural propositions might support a 3 year lag? Are people holding the ‘money’ for three years before spending it? And how does the cost increases associated with oil crisis fit in?

One can usually find any relationship one wants by eyeballing but there has to be a reason for suspecting a long lagged relationship in this case. I cannot think of one.

best wishes

bill

Cheers Bill.

I couldn’t think of any either which is why I asked the question.

I was watching a TED talk on inequality that demonstrated that the Nordic countries and Japan did much better than other western democracies not only in terms of inequality but also most indicators of social well being. If we attribute this difference to a lack of neoliberal policies I am inclined to ask Why.What is the political difference between Nordic countries and Japan and the other western nations.One difference is the countries that have adopted neoliberal policies are dominated by two main parties whereas Japan and the Nordic countries have multi party democracies. Could it be that

1 – Large corporations are responsible for ‘pushing’ neoliberal policies

2 – This is easier to achieve when only two parties need to be ‘persuaded’ through electoral donations

could it be that the point where British Labour “surrender(ed) to the neo-liberal macroeconomic Groupthink.” might co-inside with an increase in corporate donations to the Labour Party…… as they say …. follow the money!

“whereas Japan”

In Japan the LDP has been pretty much continually in power since 1955.

So you could just as easily argue that Japan has been successful because it is a political dictatorship.

Firstly, Japan is not a dictatorship; it is a democracy where one party, for whatever reason, has managed to secure a monopoly on power for a very, very long time. Secondly, I notice that you don’t give an alternative explanation as to why the Nordic countries are successful.