It's Wednesday and we have discussion on a few topics today. The first relates to…

British trade unions in the early 1970s

The mainstream economics (by which I mean neo-classical economics and its siblings in a History of Economic Thought context) constructs trade unions as being market imperfections that interfere with the freedom of supply and demand to determine optimal price (wage) and quantity (employment) outcomes. The textbooks teach students that the supply of and demand for labour without the intrusion of trade unions (and other impositions from the state – minimum wages etc) will deliver optimal outcomes for all in accordance with the respective contributions of each ‘factor of production’ (labour, land, capital etc). The real world isn’t like that at all and the determination of shares in national income is the result of a continuous struggle between labour and capital for supremacy. It is very easy to construct the trade unions has job killers in this context and to blame them for inflationary outbreaks. That certainly is how the British trade unions in the early 1970s were constructed by the conservatives and later the Labour Party itself. By the early 1970s, Monetarism was gaining a dominant hold in the academy and strong adherents in policy circles. Trade unions were considered by the Monetarists to be ‘market imperfections’ that should be destroyed by legislative fiat. Governments came under intense pressure to introduce legislation that would constrain unions. However, once we understand history, we can see the early 1970s in Britain leading up to British Labour Prime Minster James Callaghan’s speech to Labour Party Conference held at Blackpool on September 28, 1976 in a different light. It also allows us to see just what surrender monkeys the British Labour Party became after that period. This is a further instalment of my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state, which I am working on with Italian journalist Thomas Fazi. We expect to finalise the manuscript in May 2016.

Mainstream economics view of trade unions

As far back as 1881, neo-classical economists were reluctant to consider trade unions.

In his application of mathematics to the ‘moral science’ of economics, Irish economist Francis Edgeworth, who was one of the influential early neo-classical contributors and is responsible for much of the emphasis on mathematical formalisation in modern economics, considered the existence of trade unions to interfere with the smooth application of mathematics to market analysis.

A nuisance!

He wrote (1881: 51):

… throughout the whole region of in a wide sense contract, in the general absence of a mechanism like perfect competition, the same essential indeterminateness prevails; in international, in domestic politic; between nation, classes and sexes, The whole creation groans and yearns, desiderating a principle of arbitration, an end of strifes. (emphasis in original)

Which means what?

His reference to arbitration is about the need for a market to determine outcomes based on the maximisation of individual utility (a central concept in the neo-classical faith).

He argued that we only get determinate outcomes when the market is driven by the self interest on many individuals (that is, the neo-classical idea of perfect competition).

Trade unions created indeterminateness or sub-optimal outcomes.

I haven’t thought about this nonsense for years but as a student I had to spent many boring hours reading all this stuff.

[Reference: Edgeworth, F.Y. (1881) Mathematical Psychics: An Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Moral Sciences, London, E. Kegan Paul.]

As the great institutional economist, Henry Phelps Brown wrote in his classic book (1979) The Inequality of Pay that the neo-classical economists (page 16):

… have not shut their eyes to all that goes on in the labour market to make it at particular times and places not so much a market as an arena for contests of power; but they have seen these episodes as a source of aberrations about trends and relationships that are independently and more powerfully determined.

[Reference: Phelps Brown. H. (1979) The Inequality of Pay, Oxford, Oxford University Press.]

In other words, trade unions are just superficial elements – “aberrations” – on top of the main engine of the market.

He referred to a famous statement by Cambridge economics and doyen of neo-classical thinking, Alfred who in 1890 had written on what he called trade combinations (VI, vii 10):

… they present a succession of picturesque incidents and romantic transformations, which arrest public attention and seem to indicate a coming change in our social arrangements now in one direction and now in another; and their importance is certainly great and grows rapidly. But it is apt to be exaggerated; for indeed many of them a little more than eddies, such as have always fluttered over the surface of progress. And though they are on a larger and more imposing scale in this modern age than ever before; yet now, as ever, the main body of movement depends upon the deep silent strong stream of the tendencies of normal distribution and exchange; which ‘are not seen’, but which controls the course of those episodes which ‘are seen’.

[Reference: Marshall, A. (1890) The Principles of Economics, London, Macmillan.]

The mainstream view that trade unions were annoying and damaging imperfections of an otherwise perfect market (as long as the other imperfections – minimum wages, income support payments, cartels etc – were similarly absent), was used to justify the more recent legislative attacks on unions in this neo-liberal era.

It was claimed that if trade union power was squashed, markets would deliver better outcomes for workers.

While the authority to economic theory was sought, it was never the real game in town.

As the Powell Manifesto so articulately discloses – capital new well that if they could destroy the institutional structures that forced a more equal sharing of national income among the competing interests – then its hegemony would be strengthened and they would continue to call the shots.

In other words, capital knew that the control of production and the distribution of its rewards was a contest – where capital was pitted against labour.

Capitalists knew that to ‘win’ the contest they had to divide and conquer the workers on an on-going basis.

They might have been in competition with each other but when push comes to shove they identified as a class and sought to protect those class interests in whatever way they could – as the Powell strategy indicates.

Trade unions as integral social institutions of Capitalism

Phelps Brown also noted (p.17):

But the sociologist sees the main body of movement as dependent on quite other streams than those of market forces.

Which segues into how the institutional view of trade unions developed – that is, the non mainstream economists’ perspective.

The mainstream approach that cast trade unions off as ephemeral institutions, which while potentially of great nuisance could be eliminated to improve the ‘market’, belied a deeper understanding of how social institutions emerge and the functions they play.

The American institutional economists such as Arthur Ross, John Dunlop, and Clark Kerr all advanced a broader understanding of trade unions that left the mainstream approach bereft of any credibility.

The aim of our discussion is not to review the extensive literature on the evolution of trade unions.

Richard Freeman wrote (1994: 15) that trade unions:

… are probably the most idiosyncratic institutions in modern capitalism.

[Freeman, R.B. (1994) Working Under Different Rules, New York, Russell Sage.]

However, while there are substantial differences in the way unions are structured and operate across nations, the one salient aspect of unions that transcends these ‘idiosyncracies’ and provides a common organising framework is that trade unions are an institutional construct of capitalism.

They obey the logic of capitalism. They are embedded in the conflictual basis of the class conflict that defines capitalism. The nature of capitalist relations define what unions are and what they do. They can only be assessed within that construction.

In June 1865, Karl Marx delivered a speech given to the First International Working Men’s Association (the First International), which later was posthumously published (in 1898) as Value, Price and Profit.

[Reference: Marx, K. (1865) ‘Value, Price and Profit’, New York, International Co. Inc.]

The context was an earlier contribution from John Weston, a follower of the utopian socialist Robert Owen to the General Council of the First International. Weston was an “influential member of the General Council”.

In Marx’s Letter to Engels (May 20, 1865), he noted that Weston had told the General Council that:

1. that a general rate in the rise of the rate of wages would be of no benefit to the workers;

2. that the trades unions for that reason, etc., are harmful (emphasis in original).

Marx knew that if “these two propositions … were to be accepted, should be in a terrible mess, both in respect of the trades unions here and the infection of strikes now prevailing on the Continent” (emphasis in original).

In his response, Marx anticipated the later insights provided by Keynes (in 1936) that if wage costs rose there would be higher spending in the economy which the capitalists would take advantage of by passing on the wage rises in the form of higher prices.

In his rebuttal of ‘Citizen Weston’s’ claims, Marx outlined many cases in which unions do work in the interests of workers – for example, pushing for wage increases to defend the real wage after prices have been pushed up; gaining wage increases to match productivity increases; and gaining higher wages to compensate for longer working days.

He characterised these actions, which define union action in “ninety-nine out of a hundred” instances, as “as reactions of labour against the previous action of capital”. The logic of trade unions in capitalism was to respond to the actions of capital.

He reiterated that the underlying nature of capitalism involves disputes over the length of the working day and the wages to be paid, which:

… is only settled by the continuous struggle between capital and labour, the capitalist constantly tending to reduce wages to their physical minimum, and to extend the working day to its physical maximum, while the working man constantly presses in the opposite direction.

That struggle is influenced by the relative bargaining power of the two sides. When economic activity is strong, unions are stronger because unemployment is low, labour becomes scarce, profits are high and firms do not want to lose market share as a result of a lengthy industrial dispute.

Conversely, in bad times, unions have less bargaining power because the rising unemployment acts as a brake on their wage aspirations.

Within that context, Marx said that:

Trades Unions work well as centers of resistance against the encroachments of capital. They fail partially from an injudicious use of their power. They fail generally from limiting themselves to a guerilla war against the effects of the existing system, instead of simultaneously trying to change it, instead of using their organized forces as a lever for the final emancipation of the working class that is to say the ultimate abolition of the wages system.

So even within the narrow, constricting logic of labour-capital conflict, unions can clearly achieve gains for their members and that is their institutional raison d’être.

The capacity of unions to advance the well-being of their members thus varies across the economic cycle. But the power relations within capitalism also indicate that there are limits to union effectiveness, which we cannot escape from.

The owners of capital control production and employment and their expectations of future returns dictate the rate at which the capital stock accumulates over time.

In his essay Inflation and Crisis, Robert Rowthorn (1980: 133) wrote that:

Capitalists control production and they will not invest unless they receive a certain ‘normal’ rate of profit. If wages rise too rapidly, either because of extreme labour shortage or because of militant trade unionism, the rate of profit falls below its ‘normal’ level, capitalists refuse to invest, expansion grinds to a standstill and there is a crisis.

So when assessing the role of trade unions in any historical period we have to be cogniscant of the logic of the union as an institution and the limits on its effectiveness within the conflictual relationships that define capitalism.

Rowthorn (1980: 134) summed up:

A strong and militant trade union movement may force up wages and resist wage cuts even in the face of high unemployment. In a boom situation this may squeeze profits and bring expansion to a premature end, whilst there is still a large surplus of labour; and in a depression it may delay recovery by reducing profitability. This may sound like a condemnation of the trade union movement, but it is not. It is simply stating the obvious fact that, so long as capitalists control production, they hold the whip hand, and workers cannot afford to be too successful in the wages struggle. If they are, capitalists respond by refusing to invest, and the result is a premature or longer crisis. To escape from this dilemma workers must go beyond purely economic struggle and must fight at the political level to exert control over production itself.

[Reference: Rowthorn, R. (1980) Capitalism, Conflict and Inflation: Essays in Political Economy, Lawrence and Wishart, London.]

With that in mind, it doesn’t make much sense to then attack unions for being successful in what they do – that is, increases wages and reduce working hours (among other things).

That is the logic of capitalism.

But, equally, as Rowthorn notes they can be “too successful” and then the conflictual relations that define capitalism generate crisis until a resolution in the form of an abatement in the distributional conflict is found – usually through rising unemployment, but also, in more recent times, through harsh legislative constraints being placed on the capacity of unions.

The failings of British capital

The British economy was already struggling by the 1970s as a result of what might be considered a lack of focus of capital to what we might call British capitalism.

British capital was always more outward looking than say investors in Europe, Japan, or even the US.

Robert Rowthorn (1980: 67) wrote that:

British big capital has always had a major international dimension and the conditions of the post-war world led to an accentuation rather than modification of this pattern. While capital in Europe and Japan had less experience and fe facilities for direct investment overseas, combine with great opportunities in a rapidly growing homeeconomy, British big capital found itself with unexciting domestic prospects but a plethora of overseas opportunities and contacts (emphasis in original).

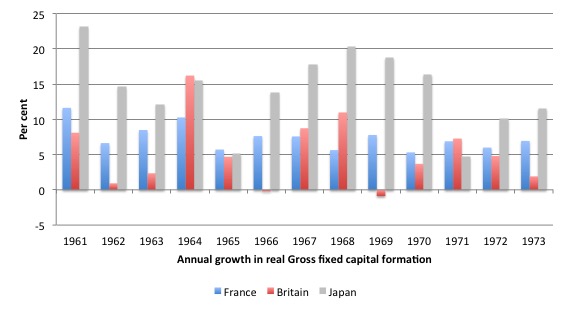

The following graph shows the annual rate of growth in real Gross fixed capital formation between 1961 and 1973 for France, Britain and Japan.

The data is from the – Annual macro-economic database – (AMECO) provided by the European Commission.

Investment averaged 14.2 per cent per annum in Japan during this period of industrial reconstruction, 7.4 per cent per annum in France and only 5.3 per cent per annum in Britain.

Private capital formation in Britain also lagged well behind that for France and Japan over the same period.

The upshot was that productivity growth in Britain lagged well behind that of France (and other European nations) and Japan and British exports struggled in international markets.

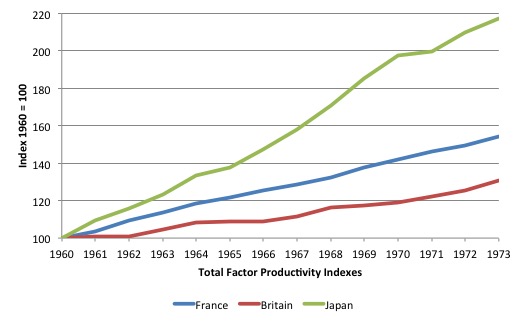

The following graph shows Total Factor Productivity indexes for France, Britain and Japan between 1960 and 1973.

In times of low productivity growth, the distributional battle between labour and capital becomes more intense because there is less opportunity for the competing claims to realise real gains. While the distributional struggle is always a zero sum game, when there is less growth to distribute, that aspect becomes more obvious.

And over the decade to 1971, the wage share in GDP in Britain fell by 2.6 percentage points compared to the rise in France of 0.4 percentage points and a fall in Japan of 5 percentage points.

It is hard to construct an argument that there were excessive wage claims outstripping productivity growth in Britain over this time.

The rising importance of global capital and Britain’s financial sector also played a part in the stagnating state of British industry during the 1960s. The opening up of capital flows and the short-termism of the British banking system biased investment flows into financial products that delivered short-term returns.

Finance capital increased pursued international speculative activities rather than investment in productive capital within Britain.

This bias towards capital export meant that British capital was prone to oppose “the measures for dynamising British capitalism, preferring – if not actually liking – the alternative of stagnation …” (Rowthorn, 1980: 68).

When Harold Wilson was first elected as Prime Minister in 1964 he attempted to bring a new sense of vitality to the domestic economy through his National Plan.

This initiative was consistent with the concept of Indicative Planning that was in vogue at the time.

This was a system of state intervention offering ‘carrots’ to firms (grants, subsidies, tax relief etc) rather than ‘sticks’ (quotas, output targets). It also was accompanied by direct public investment in infrastructure that would induce private investors to leverage further productivity gains.

The aim of the plan was to modernise British industry which had been left behind by other nations through years of neglect from the British capital owners.

Wilson created a new ministry (Department of Economic Affairs) to oversee the Plan and, politically, to offset the conservative nature of the Treasury.

An influential economist of the time, Andrew Shonfield had argued in his

1966 book Modern Capitalism: The Changing Balance of Public and Private Power that state planning mechanisms, which directed private investment without assuming public ownership, were responsible for the stronger growth in productivity in Europe, compared to Britain.

[Reference: Shonfield, A. (1966) Modern Capitalism: The Changing Balance of Public and Private Power, Oxford, Oxford University Press.]

The problem with a plan that was emphasising strong real GDP growth was that the fixed exchange rate system continually constrained the capacity of the domestic economy to grow. The currency pressures that Wilson had to deal with in the context of an on-going current account deficit (which he inherited) culminated in the decision to devalue in 1967, which effectively jettisoned the National Plan.

By the time Heath came to power in 1971, the British economy was struggling.

Trade Unions in Britain – early 1970s

The years that Edward Heath ruled (1970-1974) were marked by major industrial strife. The Conservative Heath government had observed the failure of the Bank of England’s attempts to adopt Monetarist-style money supply control and largely rejected the Friedmanite message to run fiscal surpluses, despite a growing number of Tory MPs taking up the Monetarist message and causing division within the Tory Party.

The ‘Dash for Growth’ introduced by Chancellor Anthony Barber was a conventional attempt to use fiscal stimulus to kick-start an ailing economy.

However, the Tories did not abandon their class interests and Heath determined that it was time to challenge the growing resistance of the trade unions, which had shifted to the ‘left’ as union leadership changed in several key unions (for example, the rise of Hugh Scanlon in the AEWU).

The Industrial Relations Act 1971 was specifically introduced to smash the bargaining power of the unions and to drag them and their leaders through the court system to bankrupt them.

Think about the context outlined above. Britain had endured a few decades of neglect from British capital, which had reduced its productivity growth rate, undermined its international competitiveness and intensified the focus on income distribution.

The British government then chose to force the workers to ‘pay’ for this capital neglect rather than to seek ways to stimulate capital investment and productivity growth.

It was an explicit demonstration of the Tories working directly for capital to retrench the counterveiling power that the unions had built up over many years.

Within the logic of the capitalism, it is hard to see what else the trade unions could do but to resist these attempts to destroy them.

As expected, the legislation was resisted strongly by the unions both at the peak level (Trade Union Council launched the ‘Kill the Bill’ campaign) and at the individual union level.

In January 9, 1972, the National Union of Miners (NUM) called the first national strike since the General Strike of 1926.

The 1926 Strike was in direct response to concerted attemps my mine owners to cut wages and increase hours to shore up their profits at a time that falling coal prices and rising interest rates (to defend an overavalued British pound after the flawed reintroduction of the Gold Standard in 1925) had stalled growth.

The 1972 Strike was again a reaction by the workers to extreme tactics deployed by the Government to smash the capacity of the union to defend the interests of their membership.

58.8 per cent of those who voted at the pithead favoured the general strike. The NUM also deployed so-called ‘flying pickets’, which encouraged workers at other industrial sites to go out in sympathy. The NUM targetted power stations and the gas supply to broaden the impact of their action.

By February 1972, one month into the strike, the Government was forced to call a three-day week to ration the dwindling coal supplies. A state of emergency was called to try to turn the population against the unions. That conservative strategy failed.

The Government finally offered a settlement, which included higher pay and the strike ended on February 28. The victory for the workers underlined the urgency of a more coherent response by capital along the lines of the Powell Manifesto in the US.

The next cab of the rank was the waterside industry. The Heath Government sought to abandon the long-standing “National Dock Labour Scheme”, which had safeguarded the workers on the docks from casualisation.

MORE TO COME HERE!

Conclusion

We are now close to discussing Callaghan’s speech to Labour Party Conference in 1976.

That will come soon as we analyse the causes of inflation in Britain in the early 1970s.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

Spanish translation of my Eurozone book

My current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale was published May 2015 by Edward Elgar.

It will soon be released in a cheaper paperback version as part of my contract with the publisher – for further details.

In May 2016, the Spanish language version of the book will be published and available for sale through Lola Books. Here is an advance version of the front cover:

I will announce the details of my upcoming Spanish lecture tour (May 5 to May 12, 2016) once all the venues and times are finalised.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

We have now published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m fairly sure I’ve seen charts showing that labour’s share of GDP rose to a record high in the UK in the 1970s, which suggests that unions did indeed bear some of the responsibility for the 1970s inflationary episode.

In employer/employee interactions the employer holds,most, if not all the cards. This is so even when there are some legalistic constraints on the employer as is presently the case in Australia. There are continual reports in the media about employees being ripped off by unscrupulous bosses. This applies particularly to lower paid and casual work.

I’m sure that unions are disruptive to these sort of activities. But that only applies when unions who cover these workers actually exist,when they have a significant membership and when they are allowed to legally represent their membership. In Australia at present union membership is at an all time low. Unions are pilloried as corrupt and sometimes this is justified.

At present we have a culture of union bashing which is part of the of the culture of neo-conservative economics so often condemned in this blog.It appears that the bulk of the Australian electorate are easy with this state of affairs. We need a full on economic collapse to wake these dopey fools from their comfortable slumber.

Thank you bill for this series of blogs its always interested me how exactly monterasits had so huge success with their unrealistic theories,and more importantly someone explains what really happened in this period of time.

Astonishing rhetoric about “Economics” vs Unions

“The mainstream economics … constructs trade unions as being market imperfections that interfere with the freedom of supply and demand to determine optimal price (wage) and quantity (employment) outcomes.”

That cements my prior conclusion that orthodox “Economics” was invented as a profession advising aristocrats how to manage “their” assets, physical as well as human.

It also explains things like the Irish Famine and the Highland Clearances – which aren’t included in most History of Economics textbooks.

http://www.irishhistorylinks.net/History_Links/IrishFamineGenocide.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Clearances

ps: I never appreciated before that the first “Internationale” (labor unions) were quite natural attempts to resurrect the once prominent Trade Guilds of western Europe.

“…culminated in the decision to devalue in 1967.which effectively jettisoned the National plan.”-wait why, I don’t understand why a cheaper pound would have precluded Wilson from going Ahead with the National plan-increasing domestic investment,stimulating productive output.At around the same time the South East Asian tigers were very successful in modernising their economies,raising productivity,production,wages and living standards through a similar set of policies set out by Wilson.

Why would a devalued pound prevent the Government from carrying out domestic infrastructure investment and development grants for growing firms??

Why does having a large current account deficit (which the UK has now) prevent the government from carrying out a National plan type program??

In somewhat unrelated matters – some in Europe are finally beginning to heed the right lessons from Syriza and its fate: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/slovenia-eu-euro-integration-exit-austerity/

Jake,

I’m just guessing, but maybe the devaluation was only the minimum necessary to avoid the loss of foreign currency reserves. Perhaps, it was thought that to continue the National plan would require even further devaluation, and they may have decided for political reasons (say, national pride) that it was too risky – just guessing.

Kind Regards

Bill,

Is it possible that the three-day-week exacerbated the price increases through cuts in supply relative to demand? According to the national archives workers who were temporarily unemployed would be entitled to some unemployment benefits. The Wikipedia article says that although the normal working week was resumed following the 1974 election (in March) other restrictions on electricity remained in force.

Kind Regards

Looking forward to the book, but don’t understand why devaluation in 1967 resulted in scuppering National Plan – wouldn’t this improve export potential?

I am very disappointed with this post. Having waited all week for something to criticize, once again I could not find anything to disagree with. Luckily for me, I have access to my own labor union expert, one with 50 years experience with labor unions and definitely one well on the left in the labor relations field. So I consulted him to point out those things you got wrong.

Unfortunately, my expert said that everything you write here is accurate and shows a correct understanding of what labor unions do. Since I trust him pretty good, him being my father and all, I am going to have to withdraw (or at least suspend) my pre-criticisms of this post from last week.

Hopefully, you will write something I can disagree with very soon. I will wait (with more patience) until then. Thank you in advance.

Sincerely,

Jerry Brown Jr.

Hi Bill,

Just wondering if you have any thoughts from an MMT perspective on the current situation at the Port Talbot steelworks?

Cheers

Matt

Matt, look up “3spoken”

“It appears that the bulk of the Australian electorate are easy with this state of affairs. We need a full on economic collapse to wake these dopey fools from their comfortable slumber.”

I’m certainly not easy about being paid according to a shit award that doesn’t match the work I do – let alone my contribution. However, given it’s going to be the same no matter where I go I don’t I have a choice other than to keep working above and beyond what I am paid.

I think this is the situation for many people rather than not understanding the way the system works.

Thanks Bob, interesting read.

Great article.

I noticed a couple of minor errors though:

At one point, you have Heath coming to power in 1971. That should of course be 1970 (which you give correctly a couple of lines later). (19 June 1970 according to Wikipedia)

You refer to the Trade Union Council – That should be “Trades Union Congress” (TUC).

Anyone who needs to analyse the cause of inflation in the seventies has clearly forgotten the huge rise in oil prices after yet another Arab-Israeli war. And as a member of the UCW in the seventies I have to say I never had the impression that we, the union, were running the country: Tory politicians in both parties were doing that.