In the last week, as the Federal government comes towards next Tuesday's annual fiscal statement…

Further evidence that ECB monetary gymnastics have not stimulated lending

This morning I was reading the – The euro area bank lending survey – for the first quarter of 2016, published by the European Central Bank (ECB). This is a quarterly survey that the ECB conducts which was first published in 2003. It seeks to assess the extent to which banks are lending and the factors that are influencing that behaviour. The results published in the April 2016 edition relate to the first three months of 2016 and “expectations of changes in the second quarter of 2016”. Of particular interest was the inclusion of several ‘ad hoc’ questions (outside the normal survey design) that were designed to gauge “the impact of the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme” and the “impact of the ECB’s negative deposit facility rate”. The results are fairly clear if you delve into the detail. From the April 2016 bank lending survey (BLS) we can conclude that the massive asset purchasing program and the negative interest rates have not significantly increased bank lending. We know why. It is a pity that the majority of commentators have not yet worked out the answer!

Background reading

I have considered these policy changes in these blogs (among others):

1. The ECB could stand on its head and not have much impact.

2. ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme – more smoke and mirrors.

3. The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves.

4. Building bank reserves will not expand credit.

5. Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

The recent policy terrain in Europe has reflected a misunderstanding of the problem.

First, the ECB cut interest rates (as did most central banks) in 2009. The crises deepened.

Second, then, with the Southern Member States including Italy facing bankruptcy, the ECB introduced the Securities Market Program (SMP), the first in a series of quantitative easing interventions.

While the SMP brought yield spreads down (in two major interventions – 2010 and then 2012 to stabilise Italian public debt yields) and prevented bankruptcy of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, first (in 2010) and then Italy in 2012, it did not address the problem of chronic lack of spending.

It just meant that private bond investors would continue buying the debt of troubled states knowing that they could off-load it onto the ECB in the secondary markets at profit-taking prices.

The ECB then, under pressure from the Bundesbank started pushing up interest rates (the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility) in 2011, because it claimed inflation was a risk.

The recession deepened and the Eurozone price level continued to head towards deflation.

A series of new QE-type interventions followed the July 26, 2012 – Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank – to the Global Investment Conference in London.

In that speech, Draghi made some “political” remarks along the lines that “the euro is irreversible” and that:

Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.

Prior to that, the ECB had introduced what it called major “liquidity providing operations” to complement the normal Open Market Operations (buying and selling government debt to stabilise its interest rate target).

Among these operations was the long term refinancing operation (LTRO) policy effectively gave the banks cheap 3-year loans (Round 1 on December 21, 2011 saw the banks take €489 billion from the ECB).

The aim was to provide funds to encourage the banks to increase lending. The flaw was that the ECB considered the lack of credit provision in the Eurozone was the result of a lack of bank reserves.

I covered that myth in this blog – Building bank reserves will not expand credit.

A sequence of QE or Asset Purchase Programs (APP) then followed.

At present, the ECB is pumping €80 billion per month into the purchase of “public and private sector securities” (up €60 billion since March 2016.

The aim is to boost inflation via increased spending – the belief being that if banks have more cash they will loan it out and the loans will generate increased aggregate spending which will push the inflation rate up.

It is a flawed strategy because the lack of credit growth and overall spending in the Eurozone is not the result of a lack of bank reserves but it rather a reflection of the stagnant economic outlook – low growth and continued recession in some nations, persistently high unemployment, rising income inequality, rising poverty rates, and endemic uncertainty about when the malaise will end.

Consumers are wary about increasing their debt levels and firms have sufficient capital stocks in place to satisfy the existing demand for goods and services. It is a vicious circle and flooding the banks with cash reserves doesn’t break it.

The ECB soon realised that the funds it was disbursing in purchasing the massive quantity of securities (in April 2016 the total holdings at the ECB were €1,003,063 million) were just coming back to it via the bank reserve accounts.

What to do next?

Logically, stop paying interest on reserves and do the opposite. Impose a tax on them – the negative interest rate policy introduced in June 11, 2014 saw the deposit facility rate (the rate paid on overnight deposits with the central bank) go negative. A further cut followed in September 10, 2014.

Subsequent cuts on the deposit facility saw it drop to -30 percent on December 9, 2015 and then to -0.40 percent on March 16, 2016.

The Marginal lending facility rate (“which offers overnight credit to banks from the Eurosystem”) is now down to 0.25 per cent.

This has further spread into government bond yields and a near majority of Eurozone public bonds are now being sold with negative yields.

And the ECB continues to hold vast volumes of Member State debt via its – Outright Monetary Transactions – program, which superseded the SMP.

We thus know that the ECB will not let a Member State go bankrupt but will use the threat of such to reinforces its role in the Troika to bully nations into harsh fiscal and structural changes (as in June 2015 in Greece).

The point is that apart from saving the Member States from bankruptcy none of these interventions have achieved their stated aims.

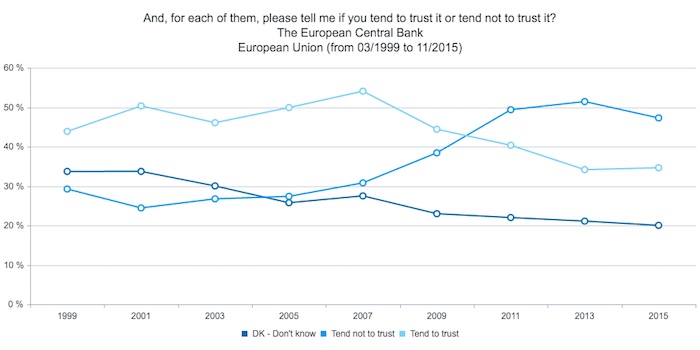

The results from Eurobarometer surveys about ‘Trust in the ECB’ reveal that an increasing proportion of respondents across the Eurozone “Tend not to trust” the central bank.

Here is a graphic for the aggregates of all Member States since 1999. Only 35 per cent (November 2015) trusted the central bank.

The results for individual nations are quite diverse (as at November 2015): Austria (41 per cent); Belgium 46; Cyprus 19; Germany 35; Spain 22; Greece 17; Slovenia 28.

The April Bank Lending Survey results

From the April 2016 bank lending survey (BLS) we can conclude that the massive asset purchasing program and the negative interest rates have not significantly increased lending.

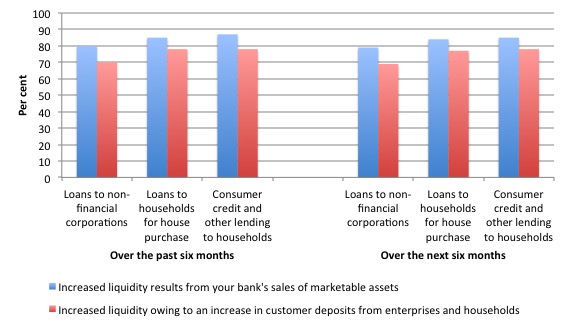

Ad Hoc Question A3 asked the following:

Over the past six months, for what purposes has your bank used the additional liquidity arising from the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme? And for what purposes will such liquidity be used over the next six months?

In other words, did the QE program, among other things, expand lending.

Close to zero respondents said that the increased liquidity “has contributed considerably” to granting loans to non-financial corporations, households for housing, or for consumer credit to households.

An overwhelming majority said that the increased liquidity has had and will not have any impact on such lending.

The following graph shows the response “Has had basically no impact” for the “Over the past six months” and “Over the next six months” periods in terms of the source of additional bank liquidity:

1. Increased liquidity results from your bank’s sales of marketable assets

2. Increased liquidity owing to an increase in customer deposits from enterprises and households

The conclusion is fairly straightforward. The APP despite the huge volumes of assets being bought by the ECB from the banks has had very little impact on bank lending.

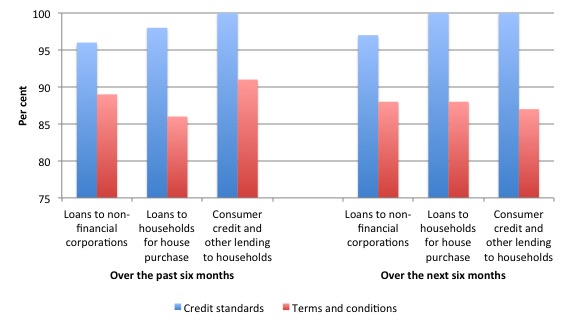

Ad hoc Question A4 asked:

Over the past six months, how has the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme affected your bank’s lending behaviour? And what will be its impact on lending behaviour over the next six months?

The two dimensions probed were “Credit Standards” and “Terms and Conditions”, “Over the past six months” and “Over the next six months”.

The following graph plots the “Has had basically no impact” response. The APP seems to have virtually zero impact on bank lending behaviour and doesn’t appear that the behaviour will change over the next 6 months.

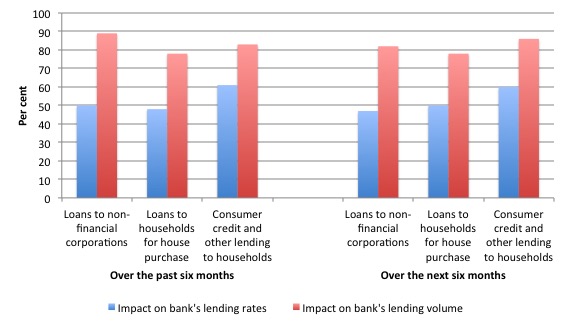

Ad hoc Question A5 asked:

Given the ECB’s negative deposit facility rate, did or will this measure, either directly or indirectly, contribute to:

– a decrease/increase of your bank’s net interest income

– a decrease/increase of your bank’s lending rates

– a decrease/increase of your bank’s loan margin (narrower spread = decrease; wider spread = increase)

– a decrease/increase of your bank’s non-interest rate charges – a decrease/increase of your bank’s lending volume

over the past or next six months?

The next graph shows the “Has had basically no impact” response for the lending rates (blue) and lending volumes (red) options.

Summary of lending rates:

- 50 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates to non-financial corporations over the last 6 months.

- 48 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates to households for housing over the last 6 months.

- 61 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates for consumer credit to households over the last 6 months.

In terms of the forward looking behaviour:

- 47 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates to non-financial corporations over the last 6 months.

- 50 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates to households for housing over the last 6 months.

- 60 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rates for consumer credit to households over the last 6 months.

Conclusion: some impact on lending rates but not much.

What about lending volumes?

- 89 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending volumes to non-financial corporations over the last 6 months.

- 78 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending volumes to households for housing over the last 6 months.

- 83 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending rvolumes for consumer credit to households over the last 6 months.

In terms of the forward looking behaviour:

- 82 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending volumes to non-financial corporations over the last 6 months.

- 78 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending volumes to households for housing over the last 6 months.

- 86 per cent of banks said the negative deposit facility rate has had No Impact on their lending volumes for consumer credit to households over the last 6 months.

Conclusion: virtually no impact on lending volumes in the past six months or expected in the next six months.

Conclusion

The problem with the emphasis on monetary policy, which has been extremely ineffective in stimulating total spending in the Eurozone is that it has been at the expense of a sensible approach to fiscal policy.

Indeed, in the earlier QE efforts, the ECB would only buy government debt in the secondary markets if it assessed the Member State government was, in fact, pursuing ‘sufficient’ austerity.

It was counterproductive. The only hope that QE has of stimulating aggregate spending is via the lower interest rates that it produces.

But if fiscal policy is simultaneously scorching the economy and undermining confidence such that households and firms reduce their spending intentions and stop borrowing, then the lower interest rates are of no assistance anyway.

The problem in the Eurozone is obvious – there is a chronic lack of spending arising from cautious households and firms and austerity-constrained Member State governments.

The ECB can build up bank reserves until the cows come home and the results will remain the same – depressed economic activity and low rates of credit growth.

At some point, people are going to understand that bank lending is not constrained by the volume of reserves that it holds.

When that understanding is achieved, then perhaps we will get to a point where were re-emphasise fiscal policy and assign monetary policy to the sidelines, where it belongs.

Paperback version of my Eurozone book now available

My current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – carries an on-line price of £99.00.

It is now available in much cheaper paperback form for £32.00.

Also the eBook is available 36.27 US dollars from Google Play or 61.45 Australian dollars from eBooks.com.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, is there a way to calculate how much profits banks and institutional investors are making, offloading securities to the ECB purchase programs? Would this system not be a sufficient reason for the Brussels financial lobby to keep the eurozone in deflation?

Where does the ECB send the funds that it receives from the interest and principal payments on the bonds and other securities that it owns? The US Federal Reserve sends its ‘profits’ (excess funds after subtracting operating expenses) to the US Treasury, but there is no such equivalent as the US Treasury in the Eurozone.

Off topic, but related to mmt. I just became enraged at Hillary Clinton for claiming that Donald Trump, if he became President, could bankrupt the United States like he did his businesses. Not to defend Trump, but apparently Hillary, despite being “the most experienced and qualified Presidential candidate in our lifetime,” still has no idea that it is impossible for anyone, even Trump, to bankrupt the Federal Government.