It's Wednesday and we have discussion on a few topics today. The first relates to…

Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future

Last week, the US Republican Party held an extraordinary convention in Cleveland, an old rustbelt manufacturing town. I say extraordinary because I guess you have to be American to understand how grown adults can systematically humiliate themselves for several days with the rest of the world looking on wondering WTF was going on! Anyway, just down the road from Cleveland is Akron, Ohio, which is being held out as a model for the new era of prosperity in advanced nations. I caution against believing that hypothesis. It was proposed in a book I have just finished – The Smartest Places on Earth – written by two Dutch writers (published 2016). It carried the subtitle “Why Rustbelts are the Emerging Hotspots of Global Innovation”. I do not recommend anyone purchase it even though it is getting rave reviews around the place. I see it as a sort of replay of the 1990s ‘New Regionalism’ mania that emerged as part of the Third Way movement, which the now discredited Tony Blair promoted as the entrepreneurial solution to turn regions into sub-national export centres to replace the ‘nation state’, that had been (according to the narrative) rendered powerless and irrelevant by globalisation. The book introduces the notion of the “Brainbelt”, which the authors claim are revitalising the “former rustbelt areas” and “bringing new competitiveness to the United States and Europe” – a sort of counter-strategy to foil the jobs lost to the low-cost nations such as China and the Asian economies in general. The problem is that the growth strategy seems to leave the worker behind!

It is clear that one of the ill effects of shifting production locations as global capitalism has evolved have been the old ‘rust belts’, which were previously the growth engines of many advanced nations.

Driven by massive investments in labour intensive production processes and a good supply of labour made possible, in part, by immigration (often forgotten by those now promoting anti-migration narratives), these industrial regions created well-paid jobs and vibrant communities, which helped to reduce income inequalities.

However, as this Fairfax article (July 25, 2015) – Donald Trump may be ignorant but he has his finger on the pulse – noted, there is now a “widespread sense of economic anxiety across the US”.

The Brexit vote would suggest that the anxiety is not confined to the US.

We read that:

Globalisation and technology, they argue, have undercut the earnings and job security of blue-collar America. But the pathologies they suffer from go much deeper than economics. Since the 1980s, divorce, crime, suicide and drug-use rates have risen dramatically among the white lower class.

The upshot is that although widening socio-economic inequality is opening ever more opportunities for the youth of the affluent, it’s making it ever harder for the youth of those left behind. And although capitalism has improved living standards immeasurably across the world, it has also created losers: their numbers are growing in the US and their leaders must find ways to ameliorate their legitimate concerns.

The article proposes that this is what is driving support from the ridiculous Donald J. Trump. And, with Hilary Clinton’s decision to enlist a neo-liberal Wall Street sympathiser (Kaine) as her running mate, I hope Trump’s support remains. At least if he is elected there might be some interesting dynamics to promote a progressive politics coming from the Democrats.

But I acknowledge that the US voters are caught between the devil and the deep blue sea!

The story line quoted above about globalisation and the losers is a forlorn one – of despair – of lives being passed by with no real end in sight.

The book The Smartest Places on Earth takes the same starting point but offers a hopeful future – of smart manufacturing to revitalise these languishing communities and regions.

Deep skepticism must be deployed when cutting through the ideas in the book. For, on the one hand, the ideas are interesting and should appeal to progressives who bemoan the loss of skills and the decline of regions.

But, on the other hand, it is too easy to get caught up in the futurism and ignore the realities.

The authors conduct a sort of inductive, world tour of regions and were taken by comments by Asian industrialists (in 2012) that they were “facing much stronger American competition again” from R&D enhanced companies who have reached a point where they can “easily squeeze” the profitability of the large Asian manufacturers.

They posed the question:

Could it be that developed countries have developed an advantage in design and manufacturing that worried the low-cost producers in Asia?

In their travels, studying various regional initiatives (such as the Eindhoven campus of Phillips), they concluded that new forms of collaboration between companies was producing the “smartest places on earth” and contradicting the perceived wisdom that globalisation was hollowing out manufacturing in the US and parts of Europe.

They started to piece together regions with common characteristics (such as Eindhoven in the Netherlands, Albany and Akron in the US) where large firms were starting to invest in new production facilities and reject low-cost labour locations – a reverse on the trends in the 1980s and 1990s.

They argued that there was proof that “Major American companies were bringing some of their most important manufacturing operations back to the United States” and locating new large-scale investments in regions where close co-operation with local university research specialisations was possible.

These university research-industrial complexes seemed to offer new sources of innovation and growth.

They wrote of the GE decision to locate in Batesville, Mississippi allowed the “iconic global corporation” to work “closely with the little-known educational institution” (Mississippi State University), the latter which “had amassed tremendous knowledge of new materials of the kind that would be needed in the creation of the next generation of superlight, ultraquiet, extremely fuel-efficient aircraft engines”.

Their hypothesis was that the old “rustbelts, former industrial citadels that had been hit hard by offshoring, suffered decline … were now coming back stronger” by “transforming themselves from also-rans into centers of innovation and smart manufacturing that we called ‘brainbelts'”.

In some cases, these new innovative regions did not have a rustbelt background (for example, San Diego) while others, (such as Akron, Ohio) clearly had such an industrial background.

A central organising unit in all these regions were the “new, university-centred brain hubs” which fast-tracked the:

… process of innovation and the creation of products that involved collegial collaboration, open exchange of information, partnerships between the worlds of business and academia, multidisciplinary initiatives, and ecosystems composed of an array of important players, all working closely together.

Innovation was a team activity rather than relying on the work of a “solo genius” or a “pair of geeks in a garage”.

Brainpower was also being shared in “unlikely places that were becoming hotspots of innovation. Most of these were cities and regions that had been ravaged by the outsources of the 1980s and 1990s”.

The hotspots were not returning “to traditional manufacturing” but rather building new R&D centres “smarter than before” and using “smart, clean, flexible” processes operated by “integrated electronics and mechanics”.

The new jobs were not based on “firing up the old equipment and hiring back laid-off workers to run the assembly lines”.

Rather, the new jobs were in “facilities” were people “worked in teams of specialists and professionals, some with advanced-skills training, some with PhDs, and, yes, some retrained former line workers”

The products were “innovative, connected, customized, and of high quality … Cheap was giving way to smart”.

The advantages for creating these new brainbelts lay in the advanced nations rather than the low-cost Asian economies, which lagged behind in educational standards etc.

These advantages included:

1. “research facilities with deep, specialist knowledge”.

2. “educational institutions”.

3. “government support for basic research”.

4. “appealing work and living environments”.

5. “the atmosphere of trust and the freedom of thinking that stimulates unorthodox idea and accepts failure as a necessary part of innovation”.

The authors claimed these characteristics were the anathema of what is found in the “hierarchical, regimented thinking” that prevails in the low-cost “Asian and MIST economies”.

They identify differences in this regard between Europe (“no common defense budget” and “innovation … has been stimulated through national research institutes”) and the US (with its “huge defense budget” and proliferation of small “start-up companies”).

So the role of government is different. One funds innovation via defense the other via the large pure and applied research agencies.

They offer the following characteristics that seem to combine to help these hotspots form:

1. They “take on complex, multidisciplinary, and expensive challenges” that require collaboration – no single player can do it.

2. A driver is the so-called “connector, an individual or group” that builds the ecosystem.

3. The region operates “in a collaborative ecosystem of contributors with research universities at their center” working with “start-ups, established companies … local government authorities, and community colleges or similar vocational institutions”.

4. They are focused “on one, or just a few, particular disciplines or activities”.

5. These components are “open to sharing knowledge and expertise” – they do not seek to monopolise knowledge.

6. They foster “physical centers” which allow small innovators to work together.

7. They act as “a magnet for talent” – work places and leisure spaces (cafes, sports, good schools etc).

8. They have venture “capital available” – often via government.

9. They have “an understanding and acknowledgement of threat” which keeps innovation at the forefront of their focus.

That is a summary of the idea.

The narrative is becoming very popular among university managers who seem to think that these sorts of developments will provide a secure future for their institutions, which are being threatened by public spending cuts and demographic trends (ageing society).

It is also fuelling the debate within the higher education sector that is promoting the so-called STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) disciplines at the expense of the traditional humanities. It is claimed that the former are more likely to promote innovation and form collaborations with private, for-profit enterprises.

Societal health and well-being (more sophisticated debates etc) which are promoted by the humanities seems to be forgotten in these never-ending debates about how the public sector can subsidise private profits.

For more discussion on this point, please read my blogs:

1. The humanities is necessary but not sufficient for social transformation.

2. I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books.

3. We need more artists and fewer entrepreneurs.

4. Technocrats move over, we need to read some books.

Corporations are also feeding the ‘Brainbelt’ narrative because it seems to be a way to justify increased government hand-outs to them in an age of fiscal austerity, which many of corporate leaders, have themselves, helped to create and promote.

It is a case of welfare for them but not for others (like the poor and unemployed).

As noted in the introduction, the same sorts of claims were made in the ‘New Regionalism’ literature that peaked in popularity in the 1990s and early 2000s, under the guise of Tony Blair’s Third Way movement.

New Regionalism proposes a series of ‘solutions’ or separate policy agendas that build on these individualistic explanations for unemployment and accepts the litany of myths used to justify the damaging macroeconomic policy stances that are now the norm in Europe and beyond.

By failing to ask the correct questions, these ‘solutions’ then appear, on first blush, to have (undeserved) plausibility.

New Regionalism emerged in the mid-1980s and was largely driven by case studies documenting economic successes in California (Silicon Valley) and some European regions (such as Baden Württemberg and Emilia Romagna).

Exactly the same sort of inductive reasoning was used to advance the narrative as the ‘brainbelt’ authors deployed. Visit a few regions which are growing and seek to generalise.

The interlinked ideas that define the New Regionalist approach to ‘space’ are consistent with the oft-heard claim from neo-liberals that the ‘national’ level of government is now getting in the way of development or that the ‘nation state’ is no longer a relevant organising unit.

New Regionalism claims that ‘the region’ is now the “crucible” (to use the words of British regional scientist John Lovering) of economic development and should be the prime focus of economic policy.

In this way, the claim is that regions have now usurped the nation state as the “sites of successful economic organisation” (Scott and Storper’s words) because supply chains (in the post Fordist era) have become more specialised and flexible given the need to deal with uncertain demand conditions.

This is, of course, the mantra that many on the Left now use to justify austerity-lite policies. They argue that globalisation has somehow eroded the capacity of the nation state to advance the well-being of the people and that regions have to take up the power vacuum.

New Regionalism advocates argue that regional spaces provide the best platform to achieve flexible economies of scope that are required to adjust to increasingly unstable markets.

These socio-spatial processes involve localised knowledge creation, the rise of inter-firm (rather than intra-firm) relationships, collaborative value-adding chains, the development of highly supportive localised institutions and training of highly skilled labour.

These dynamics require firms to locate in clusters, often grouped by new associational typologies (for example, the use of creative talent or untraded flows of tacit knowledge) rather than by a traditional economic sector such as steel.

The new post-Fordist production modes emphasise new knowledge-intensive activities encouraging local participative systems. By achieving critical mass of local collaborators, a region could be dynamic and globally competitive.

Most these claims are based on induction of regional ‘successes’ without regard for the specific cultural or institutional contexts, and lack any coherent unifying theoretical underpinning.

New Regionalism – Brainbelts – not a lot of difference in their conception, although in the latter case, there is a clear ‘public’ element that is placed at the centre of the hypothesis – both in the form of the role of the universities (which may be public) in providing the R&D skills and knowledge and the role of governments in providing spaces, zoning and … obviously FUNDING.

We will return to that point presently.

There is also a problem of evidence. It is highly disputable whether the empirical examples advanced to justify the claims made by New Regionalist proponents actually represent valid evidence at all.

For example, John Lovering (1999: 382), a critique of New Regionalism, examined the claimed made in the 1990s about Wales and concluded:

If one factor has to be singled out as the key influence on Wales’ recent economic development … it is not foreign investment, the new-found flexibility of the labour force, the development of clusters and networks of interdependencies or any of the other features so often seized upon as an indication that the Welsh economy has successfully ‘globalized’. Something else has been at work which is more important than any of these, and it is a something which is almost entirely ignored in New Regionalist thought … It is the national (British) state.

[Reference: Lovering, J. (1999) ‘Theory led by policy: the inadequacies of the New Regionalism’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23, 379-395]

That is, a supportive macroeconomic policy framework – read deficit spending from the currency-issuing government.

While many criticisms can be levelled at New Regionalism, its major weakness is that perpetuates the notion that regions can entirely escape the vicissitudes of the national business cycle through reliance on a combination of foreign direct investment and export revenue.

It is a different spin (a variation) on the ‘business cycle is dead’ notion and amounts to a denial that macroeconomic policy – that is, at the national level – can be an effective response to global trends that penetrate via the supply chains defined by trade patterns to the local region.

New Regionalism thus supports neo-liberal claims that fiscal and monetary policy is impotent and, in turn, it constructs mass unemployment as an individual phenomenon.

By ignoring the fact that mass unemployment demonstrates the unwillingness of the central government to spend sufficient amounts of currency given the non-government sector’s propensity to save, the neo-liberal position is left unchallenged and is actually reinforced and a new style of Says Law emerges with claims that post-Fordist economies need to focus on ‘supply-side architectures’.

The more recent work I am discussing in this blog – the ‘brainbelt’ ideas clearly acknowledge the role of the public sector as a key part of the innovation process both in terms of skills and knowledge and in terms of funding.

That is an advance of the more ‘free market’ approach of the New Regionalist writers.

But there are clearly shortcomings in the ‘Brainbelt’ story, which cherry picks ‘success stories’ (just like the New Regionalist literature) and excludes some important broader information that once included in the analysis seriously tempers our assessment.

Akron, Ohio is an interesting case in point. The former ‘Rubber Capital’ (named because of the concentration of the US tyre industry there) certainly became a ‘rustbelt’ town in the 1980s as jobs vanished and firms moved to other locations.

According to the ‘Brainbelt’ authors, the boss of the University of Akron, known for its research in polymer science, saw opportunities to create new forms of prosperity for the town by integrating the university’s research prowess into a new collaborative model of innovation.

The University president became in their terminology a “connector” who changed university regulations to allow its research staff to profit from commercialising their research.

With the State government (Ohio) fronting with money to “create new technology-based products, companies, industries, and jobs” a new wave of firms emerged in Akron and turned the city (and region) into the “Poylmer Capital”.

Akron was back – at the forefront of a new growth industry.

The facts, however, should temper our cheers!

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provide quite detailed data for Akron from its Midwest Information Office located in Chicago.

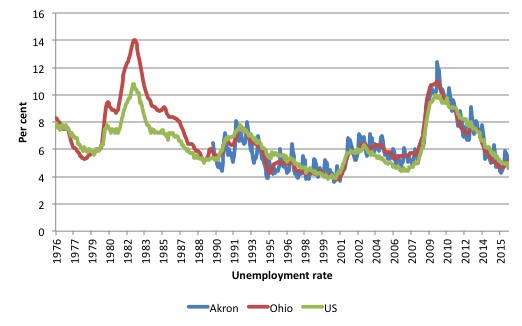

Consider the following graph, which shows the official unemployment rate for the US (green, seasonally-adjusted), Ohio (red) and Akron (blue, original) from January 1976 to May 2016. The Akron data only starts in January 1990.

The deindustrialisation of Ohio’s manufacturing industry is evident in the divergence of its unemployment rate from the national average in the early 1980s but after that its fortunes have been largely dictated by the national cycle.

Akron’s unemployment rate, in turn, is driven by the same national trends. There is no evidence that something special or peculiar is going on in Akron (as it becomes the ‘Polymer Capital’) to distinguish its economic cycle from the national cycle.

In other words, when the US economy gains strength, Akron’s labour market improves and vice versa.

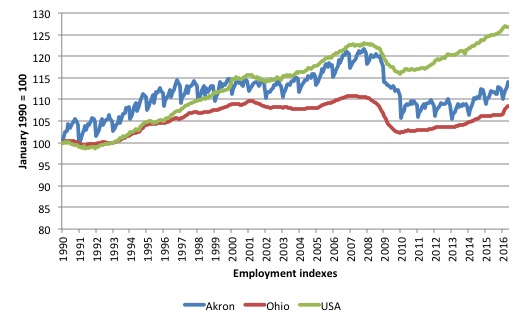

The next graph shows total employment indexes for the three labour markets (Akron, Ohio and the Nation) from January 1990 to May 2016. The reason the blue line is erratic is because it is non-seasonally adjusted data.

The message is that while Akron seems to have performed better than the state of Ohio in the immediate pre-GFC period – and followed the national trend, once the GFC hit the downturn in employment was severe.

Its total employment is still 6.2 per cent below the peak (November 2007), whereas the State remains 2 per cent below that peak. The national employment is just 3 per cent above the 2007 peak.

So there has been a considerable break in the regional behaviour of employment from the nation as a whole, which suggests that the new jobs being created in the US (even though the growth overall has been modest) are not in sectors that favour Akron, or for that matter, the State of Ohio.

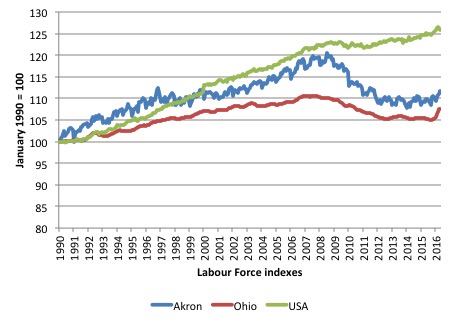

The final graph shows the labour force growth (in index form) from January 1990 to May 2016 for the three labour markets (Akron, Ohio and the Nation).

It is labour force at the national level is growing again after flattening out during the GFC – as participation rates plummetted.

For Akron and the State of Ohio labour force growth is well below the national average and is the reason that the unemployment rates have followed the national average closely, while employment growth rates have diverged.

The summary observation is that Akron does not appear to be a prospering region based on the labour force aggregates.

An assessment of the ‘Brainbelt’ hypothesis in relation to Akron was also made in this Wall Street Journal article (April 14, 2016) – Turning Rustbelts Into Brainbelts.

The author concludes that:

But in their enthusiasm for Akron’s comeback story, the authors gloss over some facts. The population of Summit County, of which Akron is the seat, has barely changed in two decades. The statistics show no influx of brainy young innovators: The county has aged faster than the country as a whole since 2000, and its median age, 40.6 years, is three years above the U.S. average. While a small number of scientific and technical jobs have been added, total employment peaked nearly a decade ago, and wages remain below the national average. In short, after 15 years the economic benefit of becoming a “brainbelt” seems to be limited.

The WSJ also examines another of the alleged ‘brainbelt’ regions – Albany, New York State.

The ‘Brainbelt’ authors argue that SUNY’s creation of a “Nanotech Complex” has attracted global funding and:

Jumpstarted by the collaboration between the state of New York, its university system, and IBM, the Hudson Tech Valley has become a thriving brainbelt.

The WSJ observes that:

What they don’t make clear is that this required breathtaking amounts of public money. “The GlobalFoundries arrangement was one of the biggest taxpayer handouts ever offered to a private enterprise in the United States,” the Albany Times Union reported in 2011. The subsidy was initially pegged at $1.2 billion, or nearly $1 million per job created in the project’s first phase-enough to pay an average plant worker’s wages for more than a decade.

While I am not taken (obviously) by the attacks on public spending by those who do not understand ‘where the money comes from’, it is clearly an issue if public money is just bankrolling private profits and failing to deliver benefits to all workers.

Is this sort of subsidy the best way to promote the well-being of all workers? Those questions are light on in the ‘Brainbelt’ book.

This raises additional issues that the book’s promotion of ‘brainbelts’ ignores.

First, the skills that promoted the prosperity in the ‘rust belts’ are not likely to be relevant in the sort of ‘smart’ manufacturing processes that might emerge in these Brainbelt regions.

How can we ensure that there is adjustment paths to ensure that all workers prosper from large public and private investments in these new innovative ‘Brainbelt’ campuses and production processes?

The authors actually consider that parallel development along the lines of the German apprenticeship system is required to integrate the schooling system with infrastructure developments and private firms.

Major public investment will be needed and a return to strong public employment can help ease this transition.

In these blogs, Australia’s response to climate change gets worse and When jobs are being lost think macro first – I discussed the concept of a Just Transition framework to ensure that the costs of economic restructuring do not fall on workers in targeted industries and their communities.

These sort of adjustments, require government support and intervention to ensure that displaced workers are able to transit into the new industries and jobs quickly.

National governments should introduce integrated employment guarantee/skills development frameworks to maintain income security and capacity building while regions adjust from old technology to new, smart processes.

On the question of incentives, I generally do not favour handing out public incentives to private firms. I see this as a denial of ‘capitalism’. If private firms want the returns then they should take the risk.

However, I do support public enterprise and partnerships with local not-for-profit co-operatives. There is so much need in the area of personal care and environmental care services now as populations age and the environmental damage of our past thoughtless industry and farming practices mount, that there is more than enough public sector work to be done to absorb displaced workers should that be required.

Second, many new jobs in these ‘smart’ manufacturing processes will be taken by robots, which will also increasingly provide services as they become more intelligent and dexterous.

As the new ‘smart’ jobs that emerge in these ‘Brainbelts’ are taken by robots, more workers will be left behind unless governments take an increasing responsibility to provide work within public employment markets.

The introduction of the – Job Guarantee – has to be seen as part of this increased public employment capacity, given that many of those displaced by industrial shifts will be those with low skills and little capacity to retrain to work in the high-tech sectors.

The public sector will have to play an increased role also in providing high skilled work for those who are displaced by robotic innovations.

As noted above, there will be growing demand for workers of all skills in the areas of personal care (as populations age) and community development, so there is little reason to fear the spread of robots.

The challenge of government is to ensure the distribution system maintains the capacity of workers who do not work in these high productivity sectors (where productivity is narrowly defined here) to enjoy real wages growth.

Third, this also suggests that a progressive agenda must be one that works to broaden the definition of productive work so that new areas of employment can be created within the public sector to provide on-going opportunities for local workers who are not absorbed in the growth provided by these ‘Brainbelts’.

Please read my blog – Employment guarantees are better than income guarantees – for more discussion on this point.

The old definition of gainful labour was biased towards activity that supported private profit generation within labour intensive, large-scale assembly production models.

So while regions work to support the ‘Brainbelt’ collaborations, the workers who live there who are not part of this increasingly capital intensive production methods, can still contribute to society through meaningful work that both provides them with income security but also ensures that income and wealth inequalities are reduced.

If productivity is enhanced by the smart part of the local labour market, then everyone benefits! That should be the aim of public investment in these smart innovation hubs.

Conclusion

The Brainbelt concept has some appeal, clearly.

But we should see it as another panacea nor another way that the public sector underwrites private profit generation while a broad swathe of the population are increasingly left behind.

There is a role for the public sector to play in revitalising declining regions. But it involves a lot more than allowing universities to become cheap tools for private capital and the public sector doling out billions to private firms who then privatise the profits.

A progressive agenda surely involves the use of smart technology to reduce the onerousness of manufacturing and to enhance productivity. But, it also requires the state to use its fiscal capacity to ensure the benefits are spread.

Further, we will not be able to escape the reality that the public sector will have to become a major employer in a progressive future to not only facilitate shifts in economic activity away from environmentally-damaging areas but also to provide a haven for those who will otherwise be left behind by the new ways of doing things.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976.

37. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

38. The British Left is usurped and IMF austerity begins 1976.

39. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy.

40. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation.

41. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1.

42. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2.

43. The case for re-nationalisation – Part 2.

44. Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear bill

thank you for your interesting blog and your insights but i see there is some problems.

1.there is already succesful personal care robots in japan which becoming better and cheaper with every year.

2.Job Guarantee is wonderful idea specially as a macroeconomic policy tool really but how many meaningful jobs can you create for lets say a small isolated city in australia or u.s which suffers from chronic high unemployment and low unskilled labour force or even public sector jobs for low skilled people before you will start to create meaningless jobs for purely macroeconomic reasons?

how many people do you need to help the community if most of this small town suffer from chronic unemployment? how many meaningful jobs can you invent for them or they can invent for themself?

(and yes i acknowledge that some of this jobs will be useful and meaningful but how many really you need?)

3.not everyone capable of attaining high skilled education there is a lot of people which is harder for them to do so and they will not able to participate in the brainbelts as you rightly said.

4.also not every low skilled work is giving to a person the same social statues and the same feel of self realisation and dignity.

yes for example being a worker in labour intensive factory (with good safety regulation and which work on green energy of course) for a good salary is maybe boring but its still give to the worker a feel of self dignity and respect which he will never get if he will be a cleaner in a school or if he will work in personal care (except if its a nurse for example).

the problem here is that even if there is low skilled jobs left after automation they are mostly jobs where people lose their self dignity by working at them (lets assume cleaners even personal care and mcjobs) and if we want to change the situation we will have to give this people very high salary increase in order to make this jobs more respectful the problem is that all this jobs already have autnomous capital which can easily replace workers if their salary is high enough (aka robots) while respectful low skilled jobs or semi skilled jobs and even skilled white colar jobs are taken away by robots digitalization and A.I technologies already (like medium scale managers workers in factories and etc).

so my solution here is that its better subsidize low skilled medium skilled and high skilled jobs which are giving to the people which practice them self realisation and self respect since capital is limited anyway and unemployed people is a wastage of labour in this case its better to subsidise jobs which will give to the people self dignity and will guarantee full employment as another part of job guarantee program.

in this case the capital will be more efficentely allocated into the sectors of the economy which have shortages of labour or to the parts where the jobs requirpments are too dangerous or the ones where its less respecftul to work in for people.

as you said at the blog of renatioanlisation efficency is not measured in the neoliberal sense of the word.

its better to have less “efficent” in neoliberal sense economy but a way more efficent and green economy in social sense of the word.

Dear Bill

Has there been deagriculturalization in the US and other developed countries? It seems to be case. After all, 100 years ago, about 50% of the population was employed in agriculture. Today, it is less than 5%. However, agricultural output today is far higher than it was 100 years. What happened is simply that the productivity of farmers rose so fast that fewer and fewer farmers were needed to produce the same amount of food. There may have been deagriculturalization in terms of employment, but there hasn’t been in terms of output.

Something similar has happened in industry. The productivity of industrial workers has been rising fast, and as a result, fewer and fewer people are needed to generate the same industrial output. Industry is different from agriculture, however, in that the consumption of industrial products can increase much more than that of agricultural output. Rich people can clutter their homes with manufactured goods, but they only need 3000 calories a day, just as poor people do. If the productivity of industry quintuples but the consumption of industrial products only triples, then employment in industry will fall by 40%.

The basic rule is: the faster productivity grows in a sector, the more likely that employment in that sector will fall, even though consumption of the goods or services produced by that sector will increase significantly. If the productivity of hairdressers were to quadruple in the next decade, then there would likely be fewer hairdressers 10 years from now, unless we all decided to visit hairdressers 4 times more often.

As to the decline in industrial employment and international trade, there is no reason to believe that international trade will necessarily have much of an impact on industrial employment as long as trade is balanced. Let’s segment trade in 3 components: primary products, services and manufactured goods. If a country has a deficit in primary products, as most developed countries do, and if it has balanced trade in services, then it must have a trade surplus in manufactured goods if its total trade is balanced. That has to be true, even if a high-wage country trades a lot with a low-wage country.

What is likely to occur when there is a lot of trade between a high-wage country and a low-wage country is that the more labor-intensive, less skill-intensive industries in the high-wage country will shrink and the other industries will expand. The losers will be the unskilled industrial workers, the winners will be the skilled industrial workers. If there is a loss of employment on account of trade, this will be due to the shrinking of the labor-intensive industries. Of course, another result will be that the average value-added of industrial workers goes up.

Be that as it may, there is no reason to believe that the decline in industrial employment in rich countries is due mainly to trade with poor countries. There is certainly no reason to believe that intensive trade between rich and poor countries has to result in a deficit in the trade of manufactured goods for the rich country. There is reason to believe, however, that trade between rich and poor countries will increase income inequality within the industrial sector.

Regards. James

“Job Guarantee is wonderful idea specially as a macroeconomic policy tool really but how many meaningful jobs can you create for lets say a small isolated city in australia”

What else do you propose people do with their day – considering all other alternatives cost money the individual doesn’t have?

Work is simply leisure you get paid for. Once you have that concept clearly in mind the solution becomes clear.

Everybody needs something to do with their day. And no that doesn’t appear automatically. It has to be organised.

Neil Wilson

you dont bothered to read all my comment if you are saying what you are saying right now,since if you read all my comment you understood that its exactly my point so pls before you are answering again pls read all of the comment and i will answer you gladly for any further questions.

“since capital is limited anyway”

Is it. Why? In most cases you just run the manufacturing a few hours more to create another one.

Think of it this way – as competition increases and jobs that need doing fall into the slot where it is no longer profitable to do a job then it will transition to the ‘effective’ public sector.

There is no need to maintain a semi-feudal system of subsidising car washing jobs when a machine will do the job just as well. Maintaining the machine is far more fulfilling for somebody than repetitive work for people that are better allocated elsewhere – perhaps gardening, street maintenance, parks beautified, graveyards maintained?

The feedback loop within the job guarantee pretty much guarantees that anything at the low level that is worth doing, but becomes unprofitable due to competition drops into its ambit. And those are generally ‘nice to have’ public services.

That way you get the car washed, more engineering maintenance jobs and nice-to-have public services – rather than just clean cars.

Neil wilson

1.yeah right? so you want to say that natural resources which create this machine are not limited?

you want to say that all the huge servers which maintain the interent big data and clouds and etc are built from materials which you can create in unlimited number?

i dont know in which planet do you live in but its clearly not planet earth

p.s and if you will start to speak with me about how the scarcity of natural resources will create a situation of good allocation of resources including labour i am welcoming you to look again at LK posts in his blogs about free trade and comparative advantage here is the same problems exactly as with free trade.

2.the problem here is that machines already maintain other machines anyway so even if its for fullfilling to maintain machines you will still have to susbsidize it.

3.in this case you will still have to maintain 2 important things first to protect jobs from automation which help people to self realise or exchanably to protect jobs which give to people the feel of self dignity.

and the second thing you will have to differntiate salaries according to effort anyway for example lets assume hypothetical situation there is an A.I which specialise on software engineering and can do all the things that Neil Wilson can more cheaply.

since Neil Wilson have self realisation and joy from being a software engineer and he studied a lot to become one its feels more just to give him higher salary than lets say to a factory worker (even though the factory worker will have to get respectful salary as well beside good safety regulation).

“so you want to say that natural resources which create this machine are not limited?”

Those are not the limiting factor in this structure at this point. The simple application of Moores law in computing shows how innovation leads to doing more and more with less as the competitive pressures are applied.

“the problem here is that machines already maintain other machines anyway so even if its for fullfilling to maintain machines you will still have to susbsidize it.”

I see no reason for that. And even when the job does become redundant you move onto another thing. There is no shortage of things to do. Just a shortage of imagination to see them.

“in this case you will still have to maintain 2 important things first to protect jobs from automation ”

I see no reason for that either, and I don’t think you have shown that in any depth.

Economic growth relies upon productivity. Even within the fairly wide limits of energy and resource recycling there is still huge scope for productivity improvements via mechanisation, and still hundreds and thousands of things that need doing that humans can do better than machines can. We are nowhere near the point where the private sector is fully automated.

So there is no reason to reduce the standard of living of the population any time soon by getting people to do anything that a machine can do more efficiently. We get the machine to do the work and get the people to do something else. That way we get better things and more things done.

And I say that as somebody who has quite a lot of experience in job enrichment and job design.

What I find is that there is a lack of imagination about the alternative work that people can undertake. And generally you start with asking them what they would like to do.

For example there are thousands of frustrated artists and actors trapped in an illiquid job market. Just think how many process job positions will pop up once you free the artists and actors from their tedium via a Job Guarantee.

The Job Guarantee isn’t just about providing jobs. It’s about providing liquidity into an illiquid market to allow more satisfactory job design and job matching amongst the population.

“A.I which specialise on software engineering and can do all the things that Neil Wilson can more cheaply.”

That’s already happened to me many, many times. You have to reinvent yourself constantly and move onto the next thing. Which is good, because doing the same thing for years tends to get boring anyway.

Change is the only constant.

At this point the approach should be to encourage the automation and realise that the task of the private sector is to eliminate as many jobs as possible within its sphere via automation and productivity improvements. It is to change the perception that the private sector creates jobs, to one where it automates away jobs and people move to the public sector for the leisure activities they get paid for.

Neil, nobody ever mentions *fuel* in these discussions and “peak oil.” I would like to see a post by Bill specifically on fuel.

The problem with “innovation” is that some of it is just rearranging things and has very little impact, and most of the big impact productivity growth comes from the discovery and adoption of cheaper denser fuels and only rather secondarily from the exploration of the new landscape of technical possibilities enabled by their cheapness and density.

A man in a dozer is as productive as 50 men with shovels not because the dozer is a great invention that enhances productivity, but because the energy source for the energy motivating its scoop is cheaper and denser than the farm product needed as energy source for the 50 labourers whose muscles motivate the shovels. Give the world a new far cheaper and far denser fuels and a new surge in productivity will happen, as people scramble to take advantage of the profit opportunities thereof.

But coal first, in low pressure and then high pressure engines, and oil later, in alternating and later continuous fuel-air engines, have been so hugely better than their predecessors that they have almost forced a massive rush to adoption.

Discovering and adopting better mineral fuel sources is the same as (this is not an analogy) discovering and adopting new extraordinarily fertile land that produces amazingly cheap and nutritious food (but with nonrenewable fertility).

The eastern desert of Arabia is probably the most fertile farmland ever discovered and put into production.

A car is far more productive than a horse drawn cart not because the petrol engine is a “Great Invention” that is far more efficient than a horse, but because its “food” (petrol) is much cheaper and lighter than the “food” (oats) powering the horse.

The great waves of productivity growth have been (nearly) entirely driven by the adoption of better (much cheaper, rather energy denser) fuels, and then, yes, optimizing the machinery using them, machinery that is however *not very useful scrap* without those fuels.

Seen from a certain point of view coal-fields and oil-fields have been the most fertile land ever discovered, capable of a “food” yield many many times larger and many many times cheaper than the most fertile land of Kansas or Ukraine, a fantastic windfall that has driven down dramatically the price of “food” for the past hundred years. It is this immense windfall that has “proven” both Malthus and Marx wrong.

The problem is that a third great fuel, cheaper and energy denser than oil, has not been found yet, and we have already optimized coal and fuel consumption as far as it is feasible, and the marginal fertility of coal-field and oil-field land is falling constantly.

This is indeed in part made clearer by looking at the energy cost of new energy, but it goes further than that.

That is what has overwhelmingly mattered, not the silly mistake of “human inventiveness” and Great Inventors and the limits with which moochers and looters shackle randian-hero wealth-creators.

A steam engine or an electrical engine are misleading named, because without the coal or oil or other fuels burned in producing the steam or electricity they wouldn’t exist, and the steam and electricity are just lossy ways to turn the energy in the fuel into work.

A paper:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w7833

“Does the “New Economy” Measure up to the Great Inventions of the Past?”

“The paper combines the Great Inventions of 1860-1900 into five clusters’ and shows how their development and diffusion in the first half of the 20th century created a fundamental transformation in the American standard of living from the bad old days of the late 19th century.”

http://www.nber.org/digest/dec00/w7833.html

“Gordon also finds that the computer, telecom, and Internet technologies pale next to the five “great inventions” of 1860 to 1900. Electricity, the internal combustion engine, the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, the entertainment, information, and communication industries, and the rise of an urban sanitation infrastructure defined the Second Industrial Revolution of 1860 to 1900. These innovations not only led to a dramatic upsurge in productivity from 1913 to 1972, but they also changed everyday life.”

“Again, the explanation for the productivity gains prior to 1970 lies mostly with the cluster of inventions developed from 1860 to 1900.”

BTW the summarizer (C Farell) also adds a very interesting point:

“A complementary explanation is that the closing of American labor markets to immigration, and of goods markets to trade, between the 1920s and 1960s gave a boost to real wages which, in turn, made labor expensive and promoted productivity growth. The post-1972 slowdown in productivity growth coincided with a reopening of labor markets to immigration and of goods markets to foreign trade.”

From my point of view that means that industries chose to use more cheap oil substituting for expensive labour, and then reversed the choice.

1.about moore law

its pretty interesting example why?

first of all moore law is already dead and no i dont think that human innovation will not get us new technological innovation for example quantum computers which maybe (according to articles which i read at least) will give us huge amount of computing power in the future for example.

but what is the problem in the later years about moore law?

the problem is that silicon transistors is not the only thing which computer chip is requiring is also requring a lot of heavy machinary to implant this really small transistors into the chip its also requiring huge amount of R&D budgets to create sufficent architecture for the chip and afterwards its requring new machinary which will implant new transistors into the chips properly.

its a lot of resources (including a lot of natural resources) which have a cost and not small one (since there is no unlimited amount of this resources) not to mention huge energy costs as well and other resources that i dont take in account.

and natural resources are

and every new upgrade of chip architecture cost more and more money to the developers of this chips and the energy costs and natural resources costs via capital equipment are not small at all and is increasing with time.

now increasing productivity is really great i never said its a bad thing but dont forget that demand is not stable as well demand have to increase to support dynamic growing and healthy economy.

if i wanted brute efficency what would be best to do is to recognize 3 things

1.demand management is important for functioning economy (so the people will able to buy all the products that the private sector sell).

2.since without proper demand management there is no full employment demand management is needed to achieve full employment.

3.unemployed labour is a waste of productvitity

4.if demand management is needed anyway and if a person which working help to increase productivity and the supply of products if you will subsidise proportionally work for the private market with fiscal deficits it will increase productivity because otherwise the person will not work and there will be less productivity.

5.if we assume that the government doing good demand management the capacity utilization of the economy should be very high (which will of course affect the prices of natural resources of energy costs and capital).

6.in this case if the workers doing a job instead of being unemployed its means that the work is more labour intensive than vice versa and its in turn means that machine or A.I or etc dont have to do this job since the worker is doing this job already.

7.is giving to the private sector more natural resources energy and capital to allocate to other sectors of the economy where is more needed or it will be complementary to the workers in the sectors where the workers work.

8.in this case you get higher productivity and full employment even in case where automated capital have absolute advantage in any sector of the economy.

but i want to keep sense of flexability in the market since i am not really into brute neoliberal model of efficency i want to keep jobs which make people to feel self dignity or where they have a sense of self fullfilment.

2.well i cant agree with you less there is a lot of jobs which can be automated already if its by digitalization if its by automated machinary or if its by A.I.

3.lack of imagination? guess what most of the people want stable job where they will feel self dignity in it most of the people as you said by yourself dont want or are not capable enough to work in some already overflood niche markets (like all the types of super creative designer jobs) and not all the people capable of being super creative entrepreneurs as well or not skilled enough to do some super creative R&D jobs.

4.i understand that job guarantee is giving more flexiablity about profession choice and i am supporting job guarantee.

5.yes there is people who like to be artists or actors or creative researchers and entrepreuners they should get funds since they are getting meaningful jobs but why do you excluding people from stable boring jobs when actually a lot of people want to do this stable boring jobs and get self sattisfaction from doing it (accountants factory workers medium scale managers and etc) this people are humans in the same way that artists and actors are humans and their preference for stability should be understandable.

6.i am happy you are able to reinvent yourself but since we have systems like deep mind which can easily learn new aspects of the profession they are specialised in the skill to reinvent yourself can become obsolote since even if you reinvent yourself and learn new skills the A.I can pretty fast learn it as well and it can create huge problems in the future for many people.

7.even though i accept the notion that work is a leisure for which you get paid for i dont believe that your plan is very good plan why?

2 reasons

1.i am sure that artists and actors will be happy to have job guarantee program but what will you do with people who want or uncapable of doing anything else and only a stable and boring job?

if a person will like to be accountant in the future or factory worker? or medium scale manager or even a mason? (if it will be automated lets assume)

1.job guarantee will not able to guarantee this kind of jobs anyway for this people job guarantee will be a kindergarden for adults where they have to find something to do,while if you will subsidise this jobs at the private sector they will still have self fullfilment from their work.

2.the other problem is that you will not able to give everyone the same salary you will have to give different people different salary based on some kind of merit (lets say education or something else) since its really important for people to get just salary otherwise there will be a lot of frustration.

Neil-there is some talk of Moore’s law reaching a limit:

‘MOORE’S LAW, the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles around every two years, is due to be revoked by 2021 as copper on silicon technology reaches its practical limits.’ (http://www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/news/2465841/moores-law-to-be-revoked-in-five-years-time).

I don’t know much about this area, but I would say that the mineral mining is still a huge ethical issue as well as environmental. Issues of built in obsolescence disguised as ‘natural evolution’ of the product are clearly an issue, rather than limiting the issue of new devices at more optimum satges of development which might limit, to some degree , the waste. This is a highly complex issue involving globalised trade/command economy issues/the nature of capitalism.

James, while you are generally right about the ratio of human input to agricultural output, you ignore how the output is produced. Mostly by industrializing agriculture by means of “unintelligent” machines and replacing what was done before by monocultural practices. The latter leads the produce to be more susceptible to pests, which require more industrial input in the form, primarily, of industrially produced pesticides (I am aware research is ongoing to improve this). The practice also degrades the soil, but artificial fertilizer is not the answer, as much of it runs off into the rivers or into ground water. I am not arguing against “progress” but the way in which commercial agriculture has developed to date can hardly be called “progressive”. The development of industrialization is another matter.

The removal of underground water on an industrial scale has become another problem. One example: Beijing is sinking as a consequence of depletion of the aquifers. Venice did this is the 17th century if I remember rightly, but the nature of the ground under Venice has led to it sinking at a much slower rate. What are the Chinese going to do? They obviously need water, not only for consumption but for industrial processes. But depleting a finite resource is not the answer. They may believe that they will find a solution before the aquifers run out, but what will happen to the city and its inhabitants in the meantime?

@Daniel M

“lets say a small isolated city in australia or u.s which suffers from chronic high unemployment and low unskilled labour force”

No such city exists in Australia.

“how many meaningful jobs can you invent for them or they can invent for themself?”

Define how capitalism knows what is useful.

“2.the problem here is that machines already maintain other machines anyway so even if its for fullfilling to maintain machines you will still have to susbsidize it.”

Tell this to someone whom spends many hours doing circuit level motherboard repair. Internet of things. Growing need for people who can repair CMOS devices or it goes into landfill.

“6.i am happy you are able to reinvent yourself but since we have systems like deep mind which can easily learn new aspects of the profession they are specialised in the skill to reinvent yourself can become obsolote since even if you reinvent yourself and learn new skills the A.I can pretty fast learn it as well and it can create huge problems in the future for many people.”

It takes thousands of human hours to program and anneal neural networks (Like deep mind) to achieve certain specific tasks in a way that is human desirable. (that is to say an observer would have trouble distinguishing the result from that of a human)

There exists no AI that can flexibly solve random problems or coordinate tools like a human. For sure the expansion of AI to take over more narrow sets of tasks is certain.

“first of all moore law is already dead and no i dont think that human innovation will not get us new technological innovation for example quantum computers which maybe (according to articles which i read at least) will give us huge amount of computing power in the future for example.”

Moores law despite the name is not a ‘law’ its an observation which has held true based on the surface area of transistors and will obviously have a limit as the ability to build gates only a few atoms wide start to behave like quantum features and stop switching. That wont happen for a few more years. There is plenty of backfill such as asynchronous computing, memristors and optimising software (fine grained parallelism perhaps) which needs more man hours than ever before.

JG can be (by design) made to work on problems the private sector does not find profitable.

sam w

1.meaningful for the person a job which will be meaningful for him to do when most likely the person is not high skilled and not pretty creative.

when a person working in the private sector he at least knows why he is doing the work and its have different psychological effect on this person even if this work is subsidised while when the government give him a job with a concept i will give you something to do so you will not be bored the person feels like in kindergarden for grown ups.

2.and there is already many devices which maintained by other machines,look i never said that every maintaince is automated but there is clear tendency to automate maintaince as well including in more in more complicated machines (correct me if i am wrong ?).

3.thats why i spoke about specialised A.I yes i know that and if lets say A.I is specialised in lets say software engineering it will not be able to solve mechanical engineering problems.

but it will be much easier to expand A.I software knoweldge to do new software engineering tasks and i think ( again correct me if i am mistaken) that to teach A.I in his specialised field or at least subfield would not take thousnds of hours.

and if i am right (i will rely on your expertise if i am wrong) in this case after some period of development enough specialised AI programs then it will be easy to automate more and more industries and sectors in the economy since it will be not too complicated to teach this specialised AI new things in the fields they are specialised in.

4.yes i know that moore law is not a real law but an observation and as i said i am sure it will not stop technological progress as i already mentioned humans are innovative enough to find ways to develop higher computing power.

i am expecting for your reply and thank you for your expertise

The problem with progressive industrial development today is that it no longer has a project that makes any sense. Big capitalism can produce all the junk we want at warp speed with less need for human involvement by the day. With fewer and fewer employed workers involved there is diminishing demand for all the junk. Unless we are planning to soon make the move to colonise other planets, there is little reason to keep the capitalist-factory model-progressive industrial project going from a progressive perspective; there just isn’t enough demand for increasing that kind of capacity any more, for both bad and good reasons.

Watching productive industrial capital, once a key economic driver, slowly wind down as clueless financial parasites bleed it to death is a terrifying thing to watch unfold.

There is a viable project here on Earth waiting for support from the central governments of the world: development and production of a green and sustainable means to achieving a comparable quality of life to what the industrial revolutions brought to participating people over the past couple of centuries.

This would be no easy task, but it is a worthy project, and since it is a hard project, necessarily undertaken with less and less access to fossil fuel and the resources they make available, it can gainfully employ most of the population into the foreseeable future.

Smart central government investment into sustainable green community development could pave the way back to an economy that allows workers to consume what they produce again.

If there is any scope for “dynamics to promote a progressive politics”, then perhaps ‘between Scylla and Charybdis’ would be a more suitable idiom, as it leaves a narrow pathway between the two undesirable options.

@Daniel M

“when a person working in the private sector he at least knows why he is doing the work and its have different psychological effect on this person even if this work is subsidised while when the government give him a job with a concept i will give you something to do so you will not be bored the person feels like in kindergarden for grown ups.”

Thats subjective. For sure what you say can be the outcome of some jobs with the JG. Indeed the way you’re thinking about the JG now was similar to my original opinion of the JG concept: my critique was to construct a situation with conditions A+B+C equals ‘gotcha’ conclusion: ‘i knew this idea would not work’.

For a moment lets just accept your caveat as true. The JG is still superior to the way unemployed are handled these days for example:

In Ireland long term unemployed can get an extra ~20 euros per week dole money by participating in what is essentially full time unpaid work and training, they have no rights and safety is poor and the participants become unmotivated do poor jobs and even self harm occurs. An entire industry of business predating on these people to do work for free is established.

Of course by aggregate the jobs are not there to transition from this work+training so a person building up skills gets taken off the program after 2 years (because by law after that time they would have to be given rights and better conditions). Some participants will become say a carpenter, work basically for free then they system by design renders all that training useless after 2 years by sacking them and forcing them to start the program again as say a cleaner.

Just juxtapose that to your critique of kindergarten JG and tell me whats a better outcome.

“clear tendency to automate maintenance as well including in more in more complicated machines (correct me if i am wrong ?)”

In a narrow sense yes maintenance is more automated but its still under guidance from a trained professional.

Its the composition of the work that changes but as soon as one component is simplified other areas for human skill open up.

A concrete example: FPGA Field programmable gate arrays took massive hassle out of prototyping programmable electronic stuff but for all the automation in this process it just opened up the need for trained people even more so to use the tool and know the domain of its uses or use it more often to solve more problems.

“A.I is specialised in lets say software engineering”

That’s just way out there for AI to replace large parts of software engineering. Also best not to conflate software ‘engineering’ with overall software ‘development’. When people talk about ‘AI’ taking over X job they never seem to realise an AI expert system could more easily replace the CEO and capitalist contrived hierarchical management system first. 😉 Where’s the stupid neoclassical theory of utility going to stand then. Were the CEO’s ‘worth it’ to earn their millions. (food for thought)

“but it will be much easier to expand A.I software knowledge… AI new things in the fields they are specialised in.”

(Sorry i shortened these paragraphs in the quote to save space).

Build a tool call it AI re-use it to make bigger better tools that replace existing tools done by humans.

This is normal we’ve been doing this for decades. Taking it a step further and copy paste machine learned knowledge into another smarter toaster is already happening.

In the literature in the late 80’s they thought the economy would fall off a cliff (the end of the utility of man) by year ~2000. These things are always being revised further into the future because there seems to be a feedback which is this stuff alters the composition of work rather than eliminate it. Plus the human side to this is jobs that get replaced often come back as art eg: stone mason or artistic stone mason.

AI is in general defined as a system that knows its environment and constraints, has a layer of knowledge which it uses to make decisions to form a plan to solve a finite problem. From this you get more specific approaches like a state of machine learning, neural networks, fuzzy reasoning, goals and domain constraints.

All that at this point int time just reinforces the need for more jobs to support this and validates the JG approach. That’s my opinion and about all i have to say on this.

Sam w

thank you for clarfying things i have an phobia from technological unemployment (i imagine a world like in a book called playing piano if you know it?) somehow you made me calmer but i want to clarify myself.

1.well i never said that JG is not a good idea i will clarify myself JG is a good idea for an artist for an actor and in case of lets assume for a moment mass scale technological unemployment for researchers doctors engineers (in case there will be hierarchy of salaries to encourage search for knowledge by studying or by the efforts which an artist put into the art or an actor and etc).

2.but my point here is that pure JG isnt the answer because not every person in the world capable or want to be a researcher or an artist there is people who get pleasure of being managers or small buisness owners or even of being simple factory workers or at least are not capable of doing something else.

in this case subsidizing their wages in order to secure them a work in the private sector for this people who just want stable boring or cant do any other i think psychologically is a better solution for this people than JG.

but subsidizing jobs in the private sector dont exclude JG i think its should be combined together because in my opinion one size fit all solutions is not really a good thing.

so yes we should be concerened about artists and researchers and etc but in case of technological unemployment we will have to find solution for ordinary people which are not highly skilled and are not creative enough to do some creative jobs we should give them a solution too.

Production of gods and services should only be about human wants and needs. Not for the reason that people should be occupied with something, whatever.

Not long ago most people had to work hard from dawn to dusk to survive, at least if they also had to produce the wants of an lavish master class. Then the mere purpose of taxes was to plunder the people of the fruits of their labour.

In gather & hunter society’s as the Saan people it’s estimated they labored at most 4 hours a day to fulfill every need and want. Including keep your home tidy and travel to and from work people today work probably 3 times that.

If we could drastically reduce the labour time and still fulfill all in society’s needs and wants why shouldn’t we? There is no longtime historical evidence that humans is designed to “work” all awake time. Rather that he occupied himself with play, games, music and storytelling.

A brief period during the last century taxes was used for public purpose. Now this is reversing, not to direct plunder but in a more sophisticated manner, to keep the masses at check with financial and monetary policies so unemployment keeps them obedient while the few can maintain and grow their riches. The few have gained much more by this policy’s than they ever had with fully occupied productive labour force.

Maybe the “economy” would do better working at full potential, but will those who own and rule this world?

But the now humans want is endless, only the fantasy is the limit. So any anxiety of mass unemployment should not be an issue. Maybe all humans should be occupied building robots?

The only way to rectify inequality is real full employment, there is no other way. As slight tendency of undersupply of labour and the market will fix it.

The capitalist is often quite clever, they calculate and foresee. The Swedish capitalists did leave the Swedish car industry in the late 80s. A chart made by an now deceased economist of Swedish total employment by sector from 1870 to 1980 with prognosis forward:

https://s26.postimg.org/q5d2vh989/Syssel800_eng.png

The trend is common in OECD countries, the capitalists did see the trend and thought of where the new growth market where, services and what services is people very willing to pay for and is essential for them? The ones that had been supplied by the public sector, so the campaign for privatization began in the late 70s and early 80s.

Daniel, the basic idea of the JG is to create new money for the specific purpose of paying people to do useful things. So no autonomy can win the contract or even compete.

The only question is who gets to decide what’s useful?

I would suggest that one on one decisions at the very local level; like getting your neighbours to help in the garden or walk your dog; should at least be an option to baseline usefulness and ensure no one need accept a job digging holes for the sole purpose of filling them in tomorrow.

I guess an dystopian future of isolated human oligarchs surrounded by autonomous support systems is possible …