Soon after the US President announced - Liberation Day tariffs - I wrote this blog…

Australian Treasurer embarrasses himself

The Australian Treasurer gave his first major statement in Sydney last week (August 25, 2016) since being barely re-elected in July. The speech – Staying the course – strengthening our resilience in uncertain economic times – was before an invited gathering of the business world who sat their listening to total nonsense from a man who disgraces the role he holds. Australians have always lagged behind developments in the rest of the world in many ways. It used to be blamed on the ‘tyranny of the distance’ (geography) but that excuse can no longer be used in this digital age. You realise how far behind the times our Treasurer is when you read articles such as this one in Foreign Policy (August 26, 2016) – The Stimulus Our Economy Needs. In that article, we read that “Now, the idea that governments, with or without the help of central banks, should spend substantial resources on creating jobs, both directly and through private sector incentives, is widely accepted among economists across the political spectrum”. Sound advice but lost on the Australian Treasurer. Bad luck for us. He is an embarrassment.

On the urgency of fiscal stimulus, the Foreign Policy article says:

The underlying policy idea is sound, even instinctive. When push comes to shove and a majority of the country’s population is struggling to improve its lot, it behooves the economic authorities – from both a social and economic standpoint – to proactively, and perhaps jointly, counter the slump.

The article goes on to discuss the benefits of a Job Guarantee and other fiscal strategies.

Sadly, the Australian Treasurer seems incapable of understanding any of the principles outlined in that article.

Here is the Treasurer looking worried as he contemplates the next lie he will spin during his speech. The signage – “The Destination for Business Intelligence” – was obviously missing a few words like “Not Here”.

The Treasurer’s pretext was that:

Australia has just concluded its 25th year of consecutive economic growth.

This has not occurred by accident – it is the product of more than 30 years of economic reform and hard work, ingenuity and sacrifice from millions of Australians.

And, if the Federal government doesn’t cut the fiscal deficit as a matter of urgency and:

we must arrest the growth in our public debt, before it is too late, by getting expenditure under control at sustainable levels … To arrest our debt we must restore the budget to balance …

Or else:

Ratings agencies have all warned that they want to see budget measures passed or this will increase the risk of a rating downgrade. They have expressed serious doubt about whether this parliament will be up to the task.

The consequences of the alternative are too stark.

And Australia will be forced to:

… know what a recession is and everything that goes along with that.

That is about the substance of the message – cut deficit spending or else go into recession.

The word unemployment (currently 5.7 per cent with suppressed participation rates) appeared once in the speech in relation to what happened in the 1991 recession. It was a passing comment.

There was no mention of underemployment (currently at 8.9 per cent).

There was no mention of the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation estimates (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) currently at 14.5 per cent of the willing and available labour force.

There was no mention of the depressed participation rate which if assessed against the most recent peak (November 2010 – at the end of the fiscal stimulus period) means that the unemployment rate would actually be around 7 per cent and the broad labour underutilisation rate would be around 16 per cent or around 2.3 million persons in a labour force of 12.6 million.

The Treasurer also failed to connect historical facts.

Australia’s real GDP growth fell to -0.7 per cent in the December-quarter 2008 after 32 positive quarters since the December-quarter 2000.

In December 2008 and again in early 2009, the then Federal Labor Government introduced a rather significant fiscal stimulus which pushed the fiscal position from a 1.7 per cent of GDP surplus in 2007-2008 to a 2.1 per cent deficit in 2008-09 – a fiscal shift of 3.8 per cent of GDP.

It was arguably to small a stimulus given that unemployment and underemployment rates rose significantly.

But the March-quarter real GDP growth rebounded to 1.1 per cent as the rest of the advanced world was slumping into a deep recession on the back of much less generous fiscal responses from the respective governments.

So to claim that Australia has enjoyed this long period without recession because of “30 years of economic reform and hard work, ingenuity and sacrifice from millions of Australians” yet overlook the obvious fact that without the significant fiscal stimulus all that “reform and hard work” etc would not have prevented Australia following the world down the recession path is a major lie.

I should add that the Australian stimulus was also reinforced by the massive fiscal stimulus that the Chinese government introduced with reversed the decline in commodity prices and helped out export sector recover from the GFC much more quickly than would have otherwise be the case.

FISCAL STIMULII saved Australia from recession – that is the fact.

To then demonise the fiscal shift that occurred in that period and suggest it was just wanton extravagance is disingenous in the extreme.

The conservatives love to play divide and conquer. In the 1990s and early 2000s, as they were in government and trying to cut income support to the massive unemployment pool that was created in the 1991 recession they developed a narrative to encourage those in employment to turn against the unemployed.

It was part of the overall neo-liberal narrative that unemployment was choice of the individuals and they were responsible for their situation.

Solution: Governments should ensure these lazy characters do not receive easy handouts.

Support Narrative: Dole bludgers, Job Snobs, Cruisers, and other vile nomenclature to blame the victims of the systemic failure to create sufficient jobs, partly due to the growing obsession with fiscal surpluses.

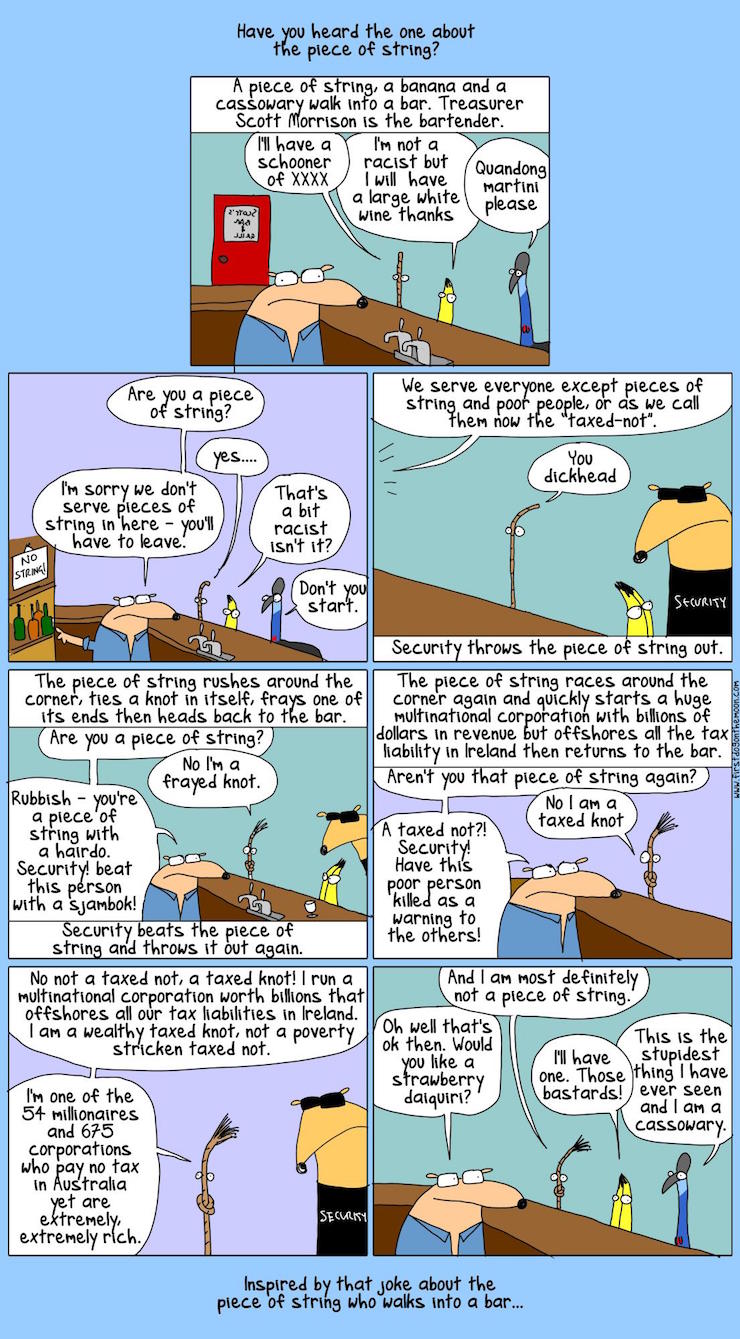

Now, the Treasurer has introduced a new divide-and-conquer nomenclature – “the taxed and the taxed nots” (see cartoon at the end for a comical reflection on this).

The Treasurer called this “a new divide”.

It is a replay on the familiar theme – “More Australians are also likely today to be net beneficiaries of the Government than contributors – never paying more tax than they receive in government payments”.

It didn’t cross the Treasurer’s dull mind to grasp the fact that if the government deliberately suppresses overall economic activity through an obsession with fiscal austerity and the result is that the labour underutilisation rate is around 16 per cent then tax revenue will be suppressed.

People cannot pay tax if they are forced into unemployment or pay less taxes than otherwise if they are forced into underemployment.

The speech featured all the usual lies.

He told the gathering that:

When Australia last faced an historic global economic shock – the GFC, we were well prepared. Our nation’s finances were in order, our AAA credit rating was in place and our banking and financial system was strong – it was well regulated, well capitalised and well managed.

To ensure we are prepared for whatever events may occur in the future we have much more work to do, especially in the area of budget repair, to strengthen our nation’s finances.

This is a common lie.

What exactly does “strengthen our nation’s finances” mean?

It is equivalent to telling the scoreboard attendants at any sporting venue that they have to strengthen their scoring mechanisms.

Why? Because they might run out of scores to digitally type into the scoreboard display or hang up on hooks if technological advance hasn’t caught up with them yet.

Sure they could run out of bits of tin with numbers to hang up if the scores went beyond feasible historical limits. But then they could just get some cardboard or bits of paper and write in numbers in marking pens and stick them up!

There is not meaning to the phrase “strengthen our nation’s finances” when referring to a fiscal status of a currency-issuing national government.

It is just an example of ideological scaremongering.

A 2 per cent public deficit to GDP ratio is no better or worse than a 4 per cent ratio as it stands. Our assessment of whether the deficit is appropriate all depends on the context.

In 1982, the late American economist Gardner Ackley said:

My own position on deficits has always been, and remains, that deficits, per se, are neither good nor bad. There are times when they are not only appropriate but even highly desirable, and there are times when they are inappropriate and dangerous. During a recession or a period of “stagflation”, deficits are nearly unavoidable, and are likely to be constructive rather than harmful.

He listed the recessions that he was familiar with (1954, 1960, 1970-71, 1975, 1981-82) and concluded that imposing fiscal austerity during those times “would be prohibitively costly – in jobs, production and real incomes – and perhaps even impossible to achieve on any terms”.

Please read my blog – A voice from the past – budget deficits are neither good nor bad – for more discussion on this point.

The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal.

It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap

However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

This second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits.

This latter position is the one taken by the current Australian government.

It appears to have lost the basic understanding that the deficits are supporting the weak growth at present. Until the non-government sector is in a position to lift its spending without relying on excessive credit to do so, then the deficits will have to remain at their current levels (or even larger).

Trying to impose fiscal cutbacks now will not only worsen the growth outlook for the nation but will, as a result, likely increase the fiscal deficit as tax revenue continues to lag behind.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs).

But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal balance will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call bad deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with good deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment.

Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end)

Gardner Ackley wrote:

Unfortunately, such “post-hoc, propter-hoc” reasoning is – as is often the case – basically erroneous.

It is much closer to the truth – although still far from the whole truth – to say that the main causal relationship between deficits and the sate of the economy runs in exactly the opposite direction: a weak and poorly functioning economy is responsible for most budget deficits.

In the current debate the politicians from both sides and the commentators have become fixated on the fiscal deficit rather than the underlying causes – the slow growth and the rise in unemployment.

If anything, the fiscal deficit in Australia is way too small given the current non-government spending growth.

To be clear:

1. The specific fiscal position today doesn’t change the capacity of the currency-issuing government to run a deficit of whatever size tomorrow.

2. The qualification to that statement is that if a currency-issuing government is running a ‘good’ deficit and the economy is at full employment, then clearly any further increase in the fiscal deficit (subject to growth in productive capacity) would be ill advised.

3. A currency-issuing government can run whatever size deficit it chooses (subject to 2) and can never run out of money. Trying to claim that the Australian government could encounter a situation where it would not be ‘funded’ is a lie. It can always fund any spending itself if it chooses to break with the unnecessary neo-liberal procedures that see public debt issued $-for-$ to match the fiscal deficit.

4. In that sense, there is no reason for public debt to increase into the future. The government should as a priority stop issuing debt and allow the deficits to manifest as increased bank reserves (and currency outstanding). That would put an end to the corporate welfare drip feed from the Treasury.

The bottom line is that a sovereign government like Australia can never run out of money and never needs to issue public debt as a matter of necessity. The public debt issuance is entirely voluntary and such voluntary actions have a habit of being quickly changed if they present too many ‘political’ problems.

5. But a currency-issuing government can service any liabilities issued in its own currency forever if it chooses. There is no sense in the statement that eventually higher taxes have to be levied to ‘pay back outstanding debt’. That is not a valid description of the history of debt maturity and reissue in Australia or elsewhere.

6. The central bank can control yields on outstanding public debt any time it chooses. Witness the negative 10-year bond rates in Japan and elsewhere.

7. Expressions like “budget repair” (now on the tip of all the mindless journalists that comment on this topic), “budget improvement”, “budget emergency” and the like are meaningless – they have no operational or significant content. They are among a plethora of misleading expressions designed to mislead the public on the true meaning of fiscal positions.

The Treasurer’s reference to the AAA credit rating is also boorish scaremongering. There is no financial advantage to the Australian government in having a AAA credit rating from the corrupt credit rating agencies.

When it comes to the ratings of government debt issued by a state that has currency issuing capacity, then the assessments have zero value and to say otherwise is a lie.

This assessment was made by the former President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and former member of the US Federal Open Market Committee, Bob McTeer. He is well-known for having ‘free-market views’ which “gave the Dallas Fed its reputation during his tenure as “The Free-Enterprise Fed”” (Source).

McTeer said on May 22, 2009 (Source):

It may just be me, but aren’t the credit rating agencies supposed to be rating credit?

Yesterday, we saw a sharp market reaction when one of the rating agencies that gave AAA ratings to mortgage-backed securities larded with subprime loans called into question the credit worthiness of Britain. As is the case with the United States and the Federal Reserve, Britain and its Bank of England have the ability to create new money if necessary to pay off its debt at maturity. There is no sovereign credit risk. There is no need for credit rating agencies to opine on the credit worthiness of sovereign debt.

That is about as succinct a statement as to the ridiculous attention that these corrupt agencies get in the media as you can get.

It is thus a total lie to claim that a government will inevitably run out of domestic funding sources. All the discussions about AAA ratings are also irrelevant.

Please read my blogs – Don’t fall for the AAA rating myth and Australia now on negative watch – so what! – for more discussion on this point.

The fiscal balance should never be a target of government policy. It is like the canary in the mine – it signals the health of the economy (mine) – and it is the latter that the government should target – full employment, sustainable growth, reducing poverty, reducing wage inequality etc.

The deficit will be whatever it is – but if the government achieves those real goals then we will all be better off.

Later in his speech, the Treasurer tried to conflate private and public debt into some ‘limit’. He said:

Our government debt to GDP is well below other AAA rated countries. However our net international investment position is the inverse.

This is because Australia has always been a net importer of capital, especially in the private sector. This has been a key source of our prosperity and development. Of itself, this is not a problem, as the investment is supported by real assets and is in productive enterprises.

However, it does mean we have less head room for Government debt than other advanced economies that fund their own debt, and why ratings agencies tend to be very focussed on Australia’s deficit and debt position. All Australian Governments must therefore be more conscious of our collective debt position. Just because rates are low, doesn’t mean the money is free – you still have to pay it back.

To say that the Australian government has “less head room” because private debt is high is a lie.

The Australian government does not issue foreign-currency denominated debt. It has no foreign exchange exposure in that regard. It can therefore always service its debt (see point 5 above).

The debt exposure of the private sector (foreign or otherwise) is irrelevant to the Federal government’s capacity to borrow or to spend (and those two capacities are not linked in the sense that the borrowing capacity determines the spending capacity).

Further, the net debt position of the non-government sector is not independent of the fiscal position the government adopts. If the government is running fiscal surpluses, then the non-government sector has to be enduring declining net wealth (in the currency of issue) and to continue its expenditure growth, ultimately has to be increasing its debt position.

A government surplus (deficit) equals $-for-$ a non-government deficit (surplus). One cannot escape that accounting reality.

Please read my blogs – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates and Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies – for more discussion on why the ratings agencies should be ignored in the context of public debt.

A little aside about our banking system.

When Lehmans Brothers collapsed on September 15, 2008, the Australian banking system entered a period of turmoil that most of us were not aware of.

The Macquarie Bank, for example, intensively lobbied the government and the corporate regulator ASIC (Australian Securities and Investments Commission) to save it from “short selling by hedge funds” and a plunging share price.

This Fairfax investigation (May 17, 2010) – MacBank’s code red – documents the situation at the time.

ASIC immediately imposed “a ban on the short selling of financial stocks” and “within weeks, the government would implement a banking deposit guarantee and a wholesale lending agreement allowing Macquarie and other banks to use the government’s stronger AAA rating to borrow money when credit markets were closed.”

The other major banks (the so-called ‘big four’) were similarly protected. They had heavy exposure to foreign wholesale debt markets which allowed them to engage in the credit frenzy in the decade leading up to the GFC.

When those markets seized up in the weeks after the Lehmans’ collapse, these banks were facing insolvency because they could not re-finance maturing short-term debt positions.

They were within days of bankruptcy.

Who bailed them out? You guessed it. The Federal government effectively guaranteed all debt (there was more than $A120 billion rolled over in this way) which kept their access to debt markets open because lenders knew the Federal government issued the currency and there was, hence, no credit risk.

Conclusion

In summary, the current situation facing Australia (in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) terms) is this:

- Australia suffered a fall in private spending as a result of the GFC.

- GDP growth fell and unemployment rose.

- In 2008, the federal government introduced a major fiscal stimulus which saved the economy from recession and GDP growth returned quickly and unemployment started falling.

- China also introduced a major fiscal stimulus which saw a recovery in commodity prices and helped the Australian mining industry recover quickly

- Hysteria from conservative think tanks, politicians, business lobby groups, and consulting companies like Deloitte Access, reinforced and promoted by a captive neo-liberal media made it politically difficult for the government and they set about on an austerity campaign to get the fiscal balance back to surplus.

- It had previously been is surplus (10 out of 11 years between 1996 and 2007) only because the private household sector had run up record levels of debt which kept spending growth going at the same time as real wages were largely flat.

- The fiscal austerity imposed from 2012 duly undermined economic growth and unemployment started to rise again. Unemployment is now higher than it was in the worst months of the GFC period.

- Compounding the fiscal cutbacks, Australia’s terms of trade have fallen substantially as mining products are in oversupply (the famous cobweb cycle in operation) and that has further hit our national income. The investment associated with the capacity building phase of the mining boom is now over and non-mining investment isn’t picking up the slack.

- The flat employment growth (with low wages growth) and falling national income has reduced the tax revenue that the government was expecting and as a result the fiscal deficit is now much higher than it anticipated. It was always going to be thus given the state of spending in the economy. It was a foolhardy exercise to pursue a fiscal surplus when private spending remains weak and labour underutilisation so high.

- The fiscal deficit is also higher because the Senate (our upper house) has not been controlled by the government and refused to pass austerity measures that were announced in the May 2014 fiscal statement because they considered them to be excessive and highly unfair.

- Overall, all that is happening is that the fiscal deficit rose as the cycle turned down as it always does. Trying to cut net public spending further in this sort of climate will only exacerbate the problem.

- The problem is a lack of growth and rising unemployment – the fiscal balance just reflects that malaise. That, in itself is no problem and trying to make out that it is a horror story is disgraceful. The problem is the rising unemployment and increased poverty rates.

- The solution is for the government to increase the discretionary fiscal deficit by increasing spending and/or cutting taxes. There is significant scope for increasing public spending on job creation programs, public health, education, infrastructure and environmental initiatives such as renewable energy.

- There is no fiscal emergency other than an urgent need for higher fiscal deficits to reduce the unemployment and underemployment.

First Dog on the Moon take on all this

The following carton from First Dog on the Moon appeared in the Guardian (August 26, 2016) under the title A piece of string, a banana, and a cassowary walk into Scott Morrison’s bar.

We learn that:

In Scott’s Bar and Grill, we serve everyone except pieces of string and poor people, or as we call them now, the “taxed-not”.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

The one thing about Brexit is the deficit fetish is dormant for now – same in the USA as election looms perhaps OZ politicos are behind the times!

Bill,

I’m certain that you are fully aware, but your writings, along with the likes of Peter Martin & Ross Gittins, tend to say that “the Conservatives fail to understand the realities of…” or “lost the basic understanding that the deficits are supporting the weak growth..”. The almost criminal part of the conservative’s agenda is that they do actually know, but are driven solely by an ideology that totally rejects government spending, even at the cost of employment. Electoral backlash be damned. We can point to the surplus & argue our way to an election victory with the support of the right wing press & a complaint electronic media.

Governments like the current conservatives are unwilling and due to their ideology unable to accept your argument. They are not too different to fundamentalist religious zealots who will nod their heads politely whilst listening to your reasoning, then circle around back to their starting point so we can go over it all over again. Look we have a surplus!

First Dog is wonderful.

Your Treasurer is pretty terrible, but so is Dan Poulter, UK MP and formerly in the Department of Health which he stepped down from last year (but is still an MP). He has also become a part-time NHS doctor. It looks as though his MP duties are not so onerous as to prevent him taking a second job, one that from all accounts is extremely demanding. (Could he be being given an easy ride?)

He has become convinced that radical, long-term funding solutions for the health and social care sectors are urgently required to prevent the system from collapsing. In his view, “[l]inking tax income with health and care spending would give people the opportunity to see how their money is being spent, and allow a legitimate debate about what is an appropriate level of taxation required to ensure a sustainable funding settlement for our NHS and social care system in the years ahead.” But this is not all. “In the Tory manifesto last year, former prime minister David Cameron promised to introduce a cap of £72,000 on the care costs for each individual, after which the state would pay. But soon after polling day, he delayed the scheme’s introduction until 2020, because money was not available.” [From Sunday’s Observer]

No insight at all into the cancer that is neoliberalism, the ideology driving all this cost cutting and related psychopathologies that have become dominant elements in our social and cultural life. And no understanding of how the national economic system operates. No understanding either that, if the system is on the verge of collapse, this is directly due to his government’s economic policies and for no other reason. It seems to be easier to believe in aliens than to understand that taxation doesn’t fund anything and that government fiscal expenditure is what is required and that such expenditure will not impoverish anyone but rather enrich the community.

Grant, you contention that the Tories understand but have a different agenda I don’t think applies to them all, but it may apply to Osborne. The evidence I have for this is that when his cuts led to decrements in GDP, he temporarily reversed them, whereas when his cuts had no such effect, he did not. This led me to hypothesize that when a cut led to poor GDP results, he realized that he might be cutting the “wrong people”, those who contributed to GDP, and reversed himself. As for those at the bottom of the pyramid, he didn’t seem to notice or care about them.

What Hammond will do is at present unclear. But I don’t expect May’s speech at the door of Number 10 to have any economic policy impact. It could have been pure PR.

I never knew income tax was the only tax in Australia!

So the Treasurer thinks we are just going to ignore GST paid by the poor then? yes some items are excluded I know. Ridiculous.

larry says:

Monday, August 29, 2016 at 22:24

Exactly. It is not that these guys are lying, its that they have no inkling of how the economy actually works, and are only interested in putting forward policies that they think will be popular.

An example is the current interest in the press and twittersphere about GERS – Government Expenditure and Reveune Scotland – that separates out the indivual data for that country within the UK. Horror story – the Scotish goverment has a much higher deficit as a proprtion of its GDP than the UK as a whole!! I have downloaded the spreadsheets from which the figures have been derived, and I was surprised to find that Scotland does not operate like a local authority or Federal State. It’s expenditure is met by the Bank of England crediting the reserve accounts of the commercial banks at which the Scottish goverment holds its procurement and HR accounts. Taxes raised in Scotland just disappear into the black hole of the Account of Her Majesty’s Exchequer along with those collected in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Now, Osborne promised that the Scots would get to keep income taxes raised in Scotland for spending on local Scottish projects. From April 6th 2016 there has been a separate tax code for residents of Scotland. So how are they going to get to “spend”it? Sounds like another bit of nonsensical Osbornomics to me. And don’t think Hammond knows any better.

As you know Nigel, Positive Money (somewhat different to MMT!) carried out research that shows that 90% of M.Ps know diddley squat about monetary operations-maybe it’s a bit like letting drivers on the road without any knowledge of the highway code (or whatever it’s called outside the UK).

A friend has been going through his clippings archive and came upon Humphrey McQueen’s review of a bio of Keating by his adviser (Edwards) (published in the ABC mag 24 Hours in Nov 1996). This quote says it all about Keating and the advisers that deluded him: “they make policy on the basis of what they remember from 1st year economics”. Edwards’ book makes it clear that after a few years Keating was willing (privately) to admit that the experts who advised hm were no better at their job than he was. Didn’t stop him continuing to go along with the nonsense though. And it goes on today

Would it be true to say this is our dumbest and most incompetent Treasurer ever?

hi grant,

whats the old saying. if you had a choice between a stuff up and a conspiracy, you would take the stuff up every time.

I bump into many of our political masters and their advisors, and I can tell you , they don’t understand the operational and accounting realities for the government. prejudice runs deep, when it come to this stuff. I have sat there and drawn t diagrams to explain the balance sheet effects, and the glazed looks I get say it all 😉

the treasurer, who ever he will be by next budget, will more than likely have to keep shifting the goal posts ever forward , just like all his recent predecessors, for this mythical budget surplus to appear.

the real elephant in the room, other than the white one in the budget papers is whether the banking systems balance sheet is going to let the treasurer get within cooey of his forecasts.

its interesting to note the level of credit growth after every crisis, has nearly halved over the period of the last 25 years. so by my reckoning, we are going to be at zero or below after the next crisis, and even a best case scenario, well below any level to keep nominal gdp growth north of 5%, which would be a minimum for the numbers to add up.

lets see how neutral all this banking system debt is going to be

of course , in good old Blighty, as soon as Osborne had buggered off they dropped the ‘surplus’ idea like a pork Pie at a Barmitzvah. No apology to the public for lying and bullshiting to them; no humble admission we got it wrong-just nothing -Osborne goes and nothing is said and these people said nothing at the time – unbelievable showe of chancers and card-sharps.

mahaish, what is “cooey”? I am sure it is a wonderful slang term, but I am unfamiliar with it.

They are disgusting, and some wonder why Corbyn, whatever his faults, is so popular, with the young particularly.

larry 22:24

Perhaps you also heard the follow-up to Poulter’s comments on the BBC and elsewhere, where the discussion was mostly along the lines of ‘well, if there’s no extra money for the NHS, perhaps we should consider charging patients directly’.

and

larry 22:32

I’m not sure that Osborne knows very much about economics, but there was a time when I did suspect that he actually understood where government spending comes from. This was during the brief period when he was talking about uncoupling state pensions from the need to have a certain numbers of years National Insurance contributions (for overseas readers: Britain has a pretend contributory state pension system – part of our tax bill is given the name NI contributions); that is, it was as if he was realizing that the Government doesn’t need taxes or ‘contributions’ in order to spend. This proposal vanished so quickly that I’m not sure I didn’t dream it.

I am not sure if I fully grasp what “issuing private debt” means. I wondered if someone could check what I say here for clarification. I have read in this blog, which I do understand, I think, that government issues bonds to banks to mop up reserves which control the interbank interest rate. I know that government issues bonds to pension funds, individuals and private banks.

The bit that is a little misty for me is that do governments issue bonds every time they create money to (for example) spend on schools and hospitals? Does that mean that they kind of spend twice?

And – does the meaning of overt monetary finance avoid the bond issue somehow and spend money directly?

If this is the case, why is the British Labour Party setting up a national investment bank to issue bonds to the Boe?

Simonski,

I did see that Positive Money report, but it didn’t seem at all substantiated to me. They could not have surveyed every (or indeed very many) MPs, so it was at best anecdotal. I would say 99% of MPs do not know how the monetary system works, and as far as I know only one parliamentarian, Lord Adair Turner, does.

Sandra,

With repect you cannot have been reading these blogs. Yes, the government issues bonds to match its spending, (or at least the difference between its spending and tax raised), but it does not have to. That’s central to MMT. Have you read Warren Mosler’s Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds? It’s available free from his website and is written in very easy to understand language. Randy Wray’s Modern Money Theory is more comprehensive and can be borrowed from the British Library.

Lloyd, yes I did hear that and couldn’t believe that what was being suggested was serious. But on reflection, I realized it was being seriously considered.

Nigel, there was a rumor shortly after Osborne took office that he had a copy of Economics for Dummies on his desk. I took it to be an urban legend, but then his performance was so much like that of a late convert to neoclassical principles, virtually if not entirely unreflective, that I wondered.

Lloyd, everyone seems to forget that part of their tax bill is in NI contributions. I am uncertain what it is now, but it was 9% for quite a long time, which is s hefty amount. I can understand the psychology of it, which appears to work — it seems to make people feel that the NHS is theirs; after all, they pay for it, as it were.

I also remember the episode you recount. It didn’t last very long, did it. Almost as if it was some kind of mistake to be withdrawn asap.

Sandra, if you follow up on Nigel’s recommendation, do consult the 2nd edition of Wray’s Modern Money Theory if you can.

Larry,

NI is worse than that. It is an immensely complex system with three classes and five thresholds. Plus the employer has to contribute as well. It’s more than 9%, although I don’t know exactly what these days as I am now over 65 and don’t pay it anymore. When I was working as an accountant I had software to calculate NI, and you could still get it worng because of the complexity of entereing the data in the correct format. What it does is to allow the government to pretend they are reducuing taxes by lowering PAYE then putting up the thresholds for NI. It does not, of course, pay for the NHS or anything else for that matter.

This man is incapable of feeling embarrassment. It is we who are embarrassed because he is supposed to be our treasurer.

Nigel, I agree of course that NI doesn’t pay for the NHS or anything else. I didn’t realize it was that complex, though I was aware it wasn’t simple to compute. I play poker (no money, only points) Monday nights with an accountant and some other guys. I’ll ask him to see if he can explain it to me. Then I’ll post his answer here, if he has one.

larry 1/1:40

You can ask me about UK NI now if you like (although maybe away from here!), as administering it is part of my job. There are in fact 6 classes and 7 categories, with corresponding sets of percentages and thresholds.

However, basically, a typical employee will pay 12% of their gross income above the basic threshold, and their employer will pay 13.8% (ditto). As you can see, it’s much higher than most people might guess. And as Nigel has pointed out, playing about with ‘National Insurance’ percentages and thresholds is a neat way for Chancellors to raise taxes without altering the headline level of 20%, which is the basic rate of ‘income tax’ and which has remained the same since 2007.

However all countries, including the UK, have plenty of other ways to mess about with tax rates and allowances and so on to give any effect they like, while still saying they’re a ‘low tax’ government (and, you could say, still helping their mates at the top end of town).

But, enough esoterica. Let’s generalize this a bit. I usually find I can get across the ‘money comes from nowhere’ point in discussions, but further along the line get into trouble if people realize that their taxes (or whatever) aren’t actually paying for what they ‘get back’. As larry suggests (30/22:26), people like the sense of ownership; that they’re contributing to society. It’s hard to find a similar emotional attachment to the actual reasons for taxation.

Lloyd, I would like to have a discussion with you away from here, but how do we get into contact without disclosing what Bill considers to be private info?

Lloyd,

Thanks for clarifying the current NI position, I’m pretty rusty having been (thankfully) out of it for two years now. Having clicked “post comment” I did then remember Class 4, but don’t recall any others. Worth also mentioning that NI contributions entitle the contributor to a pension which is calculated according to thier lifetime record. Again the contributions do not actually pay the pensions.

Larry, it would be a good thing if UK MMT followers could get together, especially if there are significant numbers living within a close distance of each other. I live in Dorset and I do know that there are other “believers” in the county. Perhaps Bill would be prepared to release the data to anyone who signs a disclaimer.

I do belong to another organisation (that Bill disagrees with so therefore shall be nameless) and they are very good at getting new people on board. In fact I am currently involved with producing a flyer for them.