It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

Latest news on European Youth Guarantee hardly inspiring

The European Commission released a new report yesterday (October 4, 2016) – The Youth Guarantee and Youth Employment Initiative three years on – which provides an updated evaluation of the progress of the policy framework designed to reduce youth unemployment. The results are as one would expect after taking into account the design limitations of the Youth Guarantee – pretty disappointing. We learn that for the 20 countries for which there is available data – “Of the 2.5 million young people that left YG schemes … during 2015, less than 0.9 million (35.5%) were known to be in employment, education or training 6 months after exit”. That is an appalling result really and signifies that the design of the program should be reappraised and changed to accord with characteristics of an ideal Job Guarantee program. These results are unsurprising, dismal though they are.

Background

I have written about the European Youth Guarantee before (in chronological order):

1. Youth Guarantee has to be a Youth Job.

2. Public employment and other matters of scale.

3. European Youth Guarantee audit exposes its (austerity) flaws.

Recall that the the Youth Guarantee was proposed by the Commission in December 2012 and formally adopted by the European Council of Ministers on April 22, 2013.

By 2012, youth unemployment in the Eurozone, particularly had reached alarming levels. In October 2012, the youth unemployment rate was 23.4 per cent in the EU27 and 23.9 per cent in the euro area, compared with 21.9 per cent and 21.2 per cent respectively in October 2011.

In Greece, the youth unemployment rate was 57 per cent in August 2012 (and rising) and 55.9 per cent in Spain and rising. For Portugal it was 39.1 per cent and rising. These types of numbers are almost unbelievable.

The EC Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion responded to these disastrous unemployment statistics for youth in a press release (December 5, 2012) – Youth employment: Commission proposes package of measures.

The EC announced their intention to introduce a Youth Guarantee scheme. In the press release from the relevant EC Commissioner László Andor we read:

High youth unemployment has dramatic consequences for our economies, our societies and above all for young people. This is why we have to invest in Europe’s young people now … This Package would help Member States to ensure young people’s successful transition into work. The costs of not doing so would be catastrophic.

Reference to “catastrophic” costs indicated that this was a situation of the highest emergency and required a response that would be commensurate with such an impending catastrophe.

The European Commission response was muted to say the least.

At the announcement on February 2013, European Commission President José-Manuel Barroso told the gathering that there was an “urgent need to tackle youth unemployment to the top of Europe’s political agenda”.

Accordingly, after announcing that the princely sum of 6 billion euros would be allocated to the Youth Guarantee (that is not a joke but looks like one), Barroso said that:

Now, with the Youth Guarantee, young people have a real chance of a better future. I call on Member States to translate this agreement into concrete action as swiftly as possible.

Barroso was always willing to make big, self-aggrandizing statements.

The Youth Guarantee fanfare was like almost everything that the European Commission does – make a big announcement splash that sounds ideal but actually amounts to nothing much at all.

Think about Jean-Claude Juncker’s grand investment plan at the beginning of last year which has amounted to pennies.

There are countless examples of this sort of grand statement backed by nothing much at all.

Anyway, as a response to the “catastrophic” youth unemployment the “Youth Employment Package” included:

… a proposed Recommendation to Member States on introducing the Youth Guarantee to ensure that all young people up to age 25 receive a quality offer of a job, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed.

The EC provided this page – Youth employment: Commission proposes package of measures – frequently asked questions – to provide further detail about the proposal.

At the time, the idea of a Youth Guarantee was very appealing and could have been a game changer if it had been sequestered from the mindless austerity that kills off any good ideas that the European Commission might come up with.

Design characteristics for employment guarantees

I wrote about the desirable characteristic that an employment guarantee should have in this blog – Employment guarantees should be unconditional and demand-driven.

Essentially, an ideal Job Guarantee would provide an unconditional and universal job offer at the minimum wage (calibrated to be an inclusive living wage) to anyone who wants a job. It would mostly eliminate unemployment (except frictional) and probably eliminate underemployment.

An ideal Job Guarantee is thus demand-driven – which means that the government employs at a fixed price up to the last person who seeks work.

There is no fiscal limit, which is appropriate for a currency-issuing government which desires to ensure that everybody who wants a job can gain access to a stable income at a socially-inclusive wage.

The European Youth Guarantee is an example of a conditional and supply-driven approach because it involves the policymaker rationing the scheme according to some rule(s) – in this case the total allowable fiscal outlay.

A reasonable prediction based on this characteristic is that the Youth Guarantee would barely put a dint in the problem it aims to address.

The initial problem relates to the scope envisaged by the scheme and the funding promises that were made.

The European Commission’s Youth Guarantee is more of an elaborate supply-side activation scheme than a job creation initiative, which makes it part of the problem and cannot be part of the solution.

creation initiative, which makes it part of the problem and cannot be part of the solution.

The ‘measures’ proposed by the European Commission’s Youth Guarantee (and my annotations) are as follows:

- “Outreach strategies and focal points” – promotion of policy initiatives, training, information

- “Provide individual action planning” – training

- “Offer early school leavers and low-skilled young people routes to re-enter education and training or second-chance education programmes, address skills mismatches and improve digital skills” – training.

- “Encourage schools and employment services to promote and provide continued guidance on entrepreneurship and self-employment for young people” – training, entrepreneurship orientation.

- “Use targeted and well-designed wage and recruitment subsidies to encourage employers to provide young people with an apprenticeship or a job placement, and particularly for those furthest from the labour market” – wage subsidies.

- “Promote employment/labour mobility by making young people aware of job offers, traineeships and apprenticeships and available support in different areas and provide adequate support for those who have moved” – training and information.

- “Ensure greater availability of start-up support services” – training, information and self-employment support

- “Enhance mechanisms for supporting young people who drop out from activation schemes and no longer access benefits” – information and mentoring

- “Monitor and evaluate all actions and programmes contributing towards a Youth Guarantee, so that more evidence-based policies and interventions can be developed on the basis of what works, where and why” – evaluation

- “Promote mutual learning activities at national, regional and local level between all parties fighting youth unemployment in order to improve design and delivery of future Youth Guarantee schemes” – talk fests.

- “Strengthen the capacities of all stakeholders, including the relevant employment services, involved in designing, implementing and evaluating Youth Guarantee schemes, in order to eliminate any internal and external obstacles related to policy and to the way these schemes are developed” – training and talk fest

So the Youth Guarantee looked like it was biased towards supply-side measures.

My summary of the proposed “Youth Guarantee” measures at the time of announcement was:

1. More training which is largely ineffective if it is outside the paid-work environment.

2. More information to be provided about jobs rather than job creation. It hard to provide information about jobs that are not there!

3. Proposals to address poor signalling which amounts to making one’s CV look better for jobs that are not there!).

4. Wage subsidies to address slow job growth barriers: of all the measures proposed this is the only one that seems to focus on the demand-side of the labour market.

That is, directly address the shortage of jobs. Wage subsidies have a long record of failure and operate on the flawed assumption that mass unemployment is the result of excessive wages.

The overwhelming problem that I see with the Youth Guarantee proposal is that it seems to skirt around the main issue – a lack of jobs. It seems to be about full employability rather than full employment.

A reasonable prediction that one would make based upon these design characteristics and the supply-side emphasis is that the Youth Guarantee would not have strong, sustaining employment outcomes.

Recent youth employment and unemployment trends

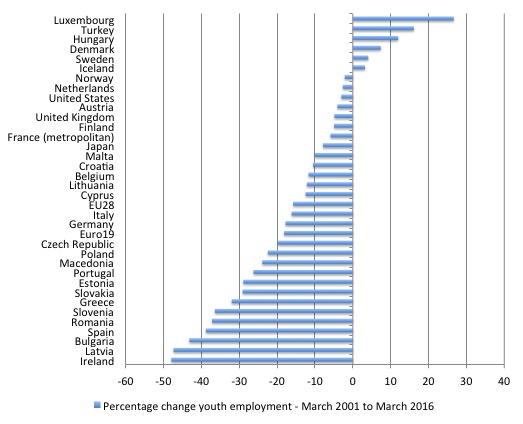

The following two graphs are fairly sobering. The first shows the percentage change in youth employment from the March-quarter 2001 to the March-quarter 2016 for a range of countries mostly European (the data is from Eurostat).

Over this period there has been a massive drop in employment for 16 to 24-year-olds in the vast majority of countries shown.

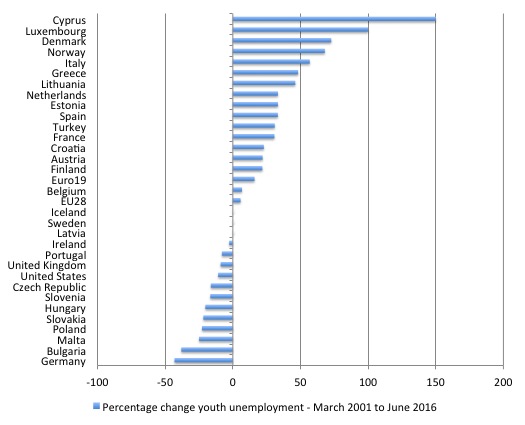

The second graph shows the percentage change in use unemployment from the March-quarter 2001 to the June-quarter 2016. In many European countries there is been a substantial rise in youth unemployment over this period which is yet to be arrested.

The conclusion is that whatever is being done by policymakers is not sufficient given that in most countries youth unemployment has remained at elevated levels for more than eight years – which means that many teenagers have entered adult hood never having worked and probably having already dropped out of the formal schooling system.

The policy failure is also evident in the significant employment contraction that is occurred over the last eight years.

Latest evidence from the European Commission evaluation

There are two angles one can take when considering this sort of program. The first relates to how far it deviates from the ideal, which I have outlined above.

The fact that there are 231 thousand more 16-24 year olds unemployed in the European Union now than there were at the low-point before the GFC tells us that the Youth Guarantee is a failure.

That is an obvious way of thinking about it.

However, we can also accept its design limitations and then assess its performance within that ‘austerity straitjacket’.

So, on its own terms, how has the scheme worked after being in operation for three years.

Answer: not very well at all.

The scale of the program is very limited. In 2015, “2.5 million young people … were registered with a YG provider” but that figure only covers “37.5% of all NEETs aged 15-24 in the EU”.

NEETs are youth who are Note in Education, Employment or Training – that is, lost to the system. The total number of NEETs in the EU in 2015 was 6.6 million.

So the scale is well below what it should be – and that is purely a reflection of the self-imposed austerity of the European Commission. The ECB could easily fund a scheme that could absorb all of the unemployed youth who seek work. But ideology prevents that desirable outcome from happening.

In “countries with the largest NEET populations” (for example, Italy, the UK, and Spain), the so-called YG “coverage rates” were low.

So the targetting of the scheme was poor. If there is a fiscal constraint on such a program then the available funds should be prioritised where the need is greatest.

The European Commission concluded in this regard that:

In general, therefore, YG schemes are still some way off the objective of reaching all young persons that become NEET after leaving school or becoming unemployed …

“Some way off” is an understatement.

The scheme is also often time-limited for each individual. For example, ” in France the YG scheme lasts a maximum of 18 months and all young people that have not taken up an offer within this time are automatically deregistered”.

And even though the pool of youth unemployment remains massive, the flows into and out of the program are stable and matched. The European Commission say that:

Outflows from YG schemes in 2015 almost matched inflows with a total of 5.4 million young people … exiting after taking up an offer or otherwise being deregistered during the year …

In other words, the scheme is not growing at a rate that will allow it to seriously deal with the youth unemployment problem that remains.

Further, the European Commission concluded that:

Of the 2.5 million young people … enrolled in a national YG scheme and still waiting for an offer at any point during 2015, well over half (1.4 million or 58.1%) had been registered for more than 4 months (i.e. beyond the target period for delivering an offer) … This 2015 result (58.1%) represents a noticeable increase compared to 2014 (50.9%) …. When the proportion of those registered in the YG for more than 4 months is high this may flag a general difficulty to deliver offers within the target period and/or an accumulation of young people that are difficult to place (and who may also need longer accompanying measures) …

Which relates to the design deficiencies in the program.

An ideal Job Guarantee program offers employment that is inclusive to the most unskilled or difficult to place worker. That offer is unconditional and is triggered immediately upon request from the individual seeking a stable income through employment.

The European Youth Guarantee is clearly struggling to move participants from registration into meaningful outcomes.

Further, as noted in the Introduction, the Evaluation Report tells us that (p.17):

Data on the situation of young people 6, 12 or 18 months after leaving the YG are not yet available for 8 of the 28 EU Member States (CZ, DE, EE, FR, NL, SI, FI and UK). Of the 2.5 million young people that left YG schemes in the remaining 20 countries during 2015, less than 0.9 million (35.5%) were known to be in employment, education or training 6 months after exit.

So a very poor outcome.

There is a qualification issued:

… the situation of just over one million (40.5%) of this cohort was unknown. In addition to those not providing any follow-up data, several other countries have limited capacity to track all young people after they leave the YG and lose contact with the YG provider … For example, the 6-month situation is unknown for almost 80% of exits in Cyprus, Romania and Slovakia, 75% in Bulgaria and nearly 70% in Poland.

In other words, the implementation framework from the program was incredibly deficient such that more than a million participants go missing once their time in the program terminates.

The other point to note is that the “Proportion of young people leaving the YG known to be in a positive situation 6 months after exit” has fallen in almost all participating countries in 2015, relative to 2014.

A well-designed and implemented scheme usually gains organisational efficiencies as the team acquires greater experience at managing the program.

That should improve the post-exit outcomes, especially given the overall labour market improved slightly between 2014 and 2015.

Conclusion

Overall, these results are what one would expect from a program with a limited resource outlay facing a massive problem.

Further, the conditionality, time limitations, lack of emphasis on job creation, and the rest of the design features of the European Youth Guarantee render it incapable of solving the massive youth unemployment problem in Europe.

While some young individuals will clearly be gaining benefit from the program as it is currently structured and implemented – and thanks be for that – millions of other young Europeans will continue to transit from their teenage years into adult hood without work, without job experience, and with deficient educational outcomes.

Their contribution to future productivity will be limited as will their ability to live to a reasonable material standard of living.

This is not rocket science!

If the European Commission was serious about prioritising the employment of young people in Europe than it has all the capacity it needs to provide a job (with training ladders if required) for any young dislocated person.

The only constraint is that imposed by the neo-liberal ideology that is created such a dysfunctional mess in that part of the world.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

José-Manuel Barroso

Jean-Claude Juncker

Self serving. Agents for neoliberalism and the banking/finance ruling elite. Liars. Incompetent. Traitors to the people of Europe. Undemocratic. Symptoms of something truly rotten in Europe and elsewhere.

I have no doubt that Bill’s Job Guarantee scheme and the way it would be financed would quite quickly provide full employment and do it in the most effective way possible. This is depressing.