I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 4

This is the fourth and final part of the discussion relating to reforming the international institutional framework. In brief, the argument is that there are several essential functions that a multilateral institutional framework has to serve that need to be incorporated within any new structure. It is clear that an agency to channel development aid remains essential. Further, it is important to create an agency that will provide liquidity to nations who are unable to access essential imported resources (such as food) without invoking exchange rate crises. While these functions seem to align with the current World Bank and the IMF, a progressive approach to service delivery in these areas would not resemble the operational procedures currently in place.

The first three parts in this series are:

1. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 1.

2. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 2.

3. 2. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 3.

Two important functions that need to be retained

In determining what the scope for a new international framework should look like we have to identify what functions are required.

There are two important functions that need to be served at the multilateral level:

1. Development aid – providing funds to develop public infrastructure, education, health services, and governance support.

2. Macroeconomic stabilisation – support for national currencies in the face of problematic balance of payments.

This function recognises that all nations should maintain sovereign currencies and float them on international markets but at the same time recognising that capital flows may be problematic at certain times and that some nations require more or less permanent assistance due to their export capacities and domestic resource bases.

Our starting point is to recognise that as long as there are real resources available for use in a nation, its government can purchase them using its currency power.

That includes all idle labour. So there is no reason to have any involuntary unemployment in any nation, no matter how poor its non-labour resources are.

The government in each country could easily purchase these services with the local currency without placing pressure on labour costs in the country.

The new multilateral institutional structure has to work within that reality rather than use unemployment as a weapon to discipline local cost structures.

But how do we address the claim that if a Job Guarantee is introduced in a nation with mass unemployment the newly employed workers will have greater purchasing power and, in the first instance, increase food consumption, which in many cases will mean higher imports.

Many of the poorest nations are dependent on imported food, in part, because of failed IMF and World Bank programs that undermined the subsistence agriculture that supported these nations.

Accordingly, the claim is that the current account of these nations will increase and depreciation will introduce inflationary impulses.

This, after all, is a primary argument used by the IMF to oppose discretionary use of fiscal deficits in poor nations.

However, all open economies are susceptible to balance of payments fluctuations. These fluctuations were terminal during the fixed exchange rate period for external deficit countries because they required the government to be continually suppressing domestic demand and local activity in order to keep the imports down.

So under this type of exchange rate regime, nations were biased towards mass unemployment and recession.

For a flexible exchange rate economy, the exchange rate does the adjustment. Is there evidence that fiscal deficits create catastrophic exchange rate depreciations in flexible exchange rate countries? None at all.

There is no clear relationship in the research literature that has been established. If you are worried that rising net spending will push up imports then this worry would apply to any spending that underpins growth including private investment spending. The latter in fact will probably be more ‘import intensive’ because most of the poorer nations import capital.

Indeed, well targetted government spending can create domestic activity which replaces imports. For example, Job Guarantee workers could start making things that the nation would normally import including processed food products.

Moreover, a fully employed economy with a skill development structure embedded in the employment guarantee are likely to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in search of productive labour.

So while the current account might move into deficit as the economy grows (which is good because it means the nation is giving less real resources away in return for real imports from abroad) the capital account would move into surplus. The overall net effect is not clear and a surplus is as likely as a deficit.

Finally, even if ultimately the higher growth is consistent with a lower exchange rate this is not something that we should worry about. Lower currency parities stimulate local employment (via the terms of trade effect) and tend to damage the middle and higher classes more than the poorer groups because luxury imported goods (ski holidays, BMW cars) become more expensive.

These exchange rate movements will tend to be once off adjustments anyway to the higher growth path and need not be a source of on-going inflationary pressure.

But what about the case of a nation that is dependent on imported food or, perhaps, energy?

The management of this type of situation would become one of the core functions of the new multilateral institution.

Where imported food dependence exists – then the role of the international agency would be to buy the local currency to ensure the exchange rate does not price the poor out of food. This is a simple solution which is preferable to forcing these nations to run austerity campaigns just to keep their exchange rate higher.

The international community would agree that this support would be on-going and unconditional as long as the link between the imported food (energy) and the foreign exchange intervention was clear.

It was also claimed that the (implied) fiscal deficits would be inflationary. Why? First, why is net government spending inflationary whereas private investment spending not?

There is no answer other than an ideological disposition against public spending. Second, we always have to go back to why inflation occurs. If nominal spending exceeds the real capacity of the economy to respond then you get inflation if the growth of excess nominal spending is continuous.

If a nation has no spare real resources available then, clearly, further non-inflationary growth is impossible and the poverty can only be addressed by taking real resources of those who currently have them and giving them to the poor or giving the nation real resources from other nations via development aid.

The first solution requires internal redistribution via taxation whereas the second requires a renewed commitment to development aid that gets real productive and consumption resources into the hands to those who need them.

In the first case, the redistributive solution, has nothing to do with financial constraints on government spending nor indicates that taxation finances that spending. Neither are true.

What it indicates is that any spending (public or private) can come up against a real resource constraint and the only non-inflationary solution is to redistribute who has access to those real resources.

So taxation can play this role by reducing the capacity of some to spend (access real resources) and providing more access (via government spending) to those previously deprived. All of which would be occuring at full employment.

The multilateral institution would not force nations to cut taxes for the higher income earners in return for aid, which is the bias in current IMF and World Bank interventions. It would recognise the role of taxation was to create non-inflationary space for the sovereign government to command real resources to fulfil its socio-economic program.

The reality is that there are many idle resources in the poorer nations – land, people and materials – that can be bought by government and mobilised to reduce poverty without causing inflation.

Immediately assuming that fiscal deficits will be inflationary is just a neo-liberal strategy to limit the relative size of the government in the economy.

In fact, these nations will likely have to run continuous fiscal deficits for many years to allow the non-government sector to accumulate financial assets and provide a better risk management framework.

How did the advanced nations develop?

A related question that impacts on our thoughts on the way in which a multilateral development and macroeconomic stabilisation institution might work is to consider how the existing advanced nations became that way.

In other words, how did the advanced nations develop?

History, tells us that if the type of policies that are now advocated by the IMF and World Bank were imposed upon what are now the advanced nations in the early stages of their development, then they would have, in all likelihood, remained poor

While the experience of the advanced nations has been different (for example, the US developed somewhat differently to, say South Korea), there have been several common elements, all of which run counter to the neo-liberal ideology imposed by the IMF and the World Bank on the poorest nations in the modern era.

In other words, development aid must support the type of processes that have been proven time and again to be successful and helped the advanced nations develop.

A coherent public sector supporting infrastructure development, developments in education and health and urban settlements, should be at the centre of any development strategy.

Forcing nation states to impose harsh cuts on public services and deny the human capital areas such as education and health of the central funds is a recipe for disaster for any emerging country.

How many institutions?

Does a progressive future require more than one institution to serve the functions noted above?

To avoid mission creep and to clearly demarcate responsibilities it is probably preferable to have two major multilateral institutions:

1. The first entrusted with the provision of development aid – perhaps a Global Sustainable Development Bank. It would recognise the need for environmental sustainability and the integrity of the human settlement.

2. The second entrusted with provision of necessary liquidity to prevent exchange rate crises – perhaps a Global Liqudity Bank.

While these two new institutions might resemble the current World Bank and IMF duopoly, the operations of these new institutions would be more clearly defined to avoid overlap and would become progressive rather than neo-liberal forces serving the interests of US financial capital.

The other advantage of having two institutions rather than one is to provide some counterbalance as a defence against entrenched Groupthink.

The location of these institutions, the tenure of the staff employed, the incentive schemes governing the pay structures, and the other elements that have worked in the case of the IMF and the World Bank, to create the destructive Washington Consensus, would have to be carefully considered.

Institutional diversity

As at April 30, 2015, there were 775 IMF staff (out of 2613) with PhD degrees and 485 came from programs offered in the United States.

The majority of these doctoral staff members were economists.

In a report from the Independent Evaluation Office for the IMF, it was argued that the the diversity of IMF research:

… was limited by the lack of diversity in staff’s educational backgrounds.

Any new multilateral institution must seek to increase diversity. While the IMF, for example, publishes an annual diversity report its emphasis is on gender and country representation in its staffing proportions rather than recognising that the dominance of US-educated economists (irrespective of the nationality of the staff member) locks the institution into neo-liberal Groupthink.

The lack of diversity in post graduate programs in economics in US universities ensures that a particular mindset will be inculcated within the graduates.

The failures of economics as a intellectual discipline are thus transmitted into these multilateral institutions and are reflected in the policies that transpire.

Any new institution should dilute the importance of economists and embrace the insights that other social scientists (for example, sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists) can provide to societal development

Debt forgiveness

The Jubilee 2000 campaign sought to have all third world debt cancelled by the year 2000.

The movement fractured into a number of regional agendas.

There is significant resistance to the idea of debt forgiveness. The claim expressed by conservative economist Robert Barro in a Business Week Op Ed (April 10, 2000) is representative:

Such debt forgiveness amounts to a form of foreign aid in which the recipient gets the money only by following bad policies that over time fail to achieve sustained economic growth. Foreign aid has a poor record at promoting prosperity, and aid in the form of debt forgiveness is sure to have worse effects.

[Reference: Barro, R.J. (2000) ‘If We Can’t Abolish the IMF, Let’s At Least Make Big Changes’, Business Week, April 10, 2000. LINK]

The question evaded is what has been the role of the IMF and the World Bank in creating the situation where the poorest nations endure debt burdens that they cannot pay back and which the debt servicing fatally compromises their ability to advance the prosperity of their citizens?

Simple case studies abound. Take the example of Ghana, which had established viable rice production aided by farm subsidies provided by the government.

Enter the IMF and the World Bank who pressured Ghana to cut the farm subsidies in order to gain development loans and, as a consequence, destroyed a viable industry and created a food-import dependency for the nation.

The UK Guardian article (April 11, 2005) – Ghana pays price for west’s rice subsidies – recounts the collapse of Ghana’s rice industry over the previous 30 years which has impoverished farmers, created hunger and generated mass urban unemployment as rural folk have been forced to seek work in the cities.

We read:

In the early 1980s conditions attached to loans given to Ghana by the IMF and the World Bank resulted in the country liberalising its markets and cheap imported rice flooding the market …

At the same time it was driving farm incomes down in Ghana, “the US, Japan and the EU subsidised their rice production by $16bn (£8.48bn) in 2002 … The US policy is particularly harmful for the rice-growers of Ghana. In 2003, the US paid $1.3bn in rice subsidises to its farmers and sold the crop for $1.7bn, effectively footing the bill for 72% of the crop.”

So large farms in Arkansas (dominated by one mega company, “Ricelands”) were able to offer rice onto world markets at a price-quality mix that undercut the Ghanian output as the subsidies were retrenched under coercion from the IMF and the World Bank.

The IMF and the World Bank thus favoured big and protected US corporate interests and Ghanian external debt rose as it was flooded with imported rice.

So when we frame the debt jubilee issue in neo-liberal terms by claiming that debt forgiveness or just entrench ‘inefficient’ and wasteful local resource usage, we should think of Ghana, which is representative of many instances where the conditionality imposed upon nations by the IMF and the World Bank, helped destroy the local productive sector, created increased import dependencies, and as a consequence forced even more debt onto these struggling nations.

A truly progressive policy agenda would impose a complete debt Jubilee as a starting point for a revised sustainable development strategy for the poorest nations in the world.

Development Aid

In 1970, the 25th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations passed a – Resolution on Financial resources for development – (Paragraph 43) that said:

In recognition of the special importance of the role that can be fulfilled only by official development assistance, a major part of financial resource transfers to the developing countries should be provided in the form of official development assistance. Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.

The UN agreed that while “developing countries must, and do, bear the main responsibility for financing their development” it was still beholden on each “economically advanced country” to provide substantial resources by way of overseas development aid to assist nations that were less well-off.

The – Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development – which emerged out of the Monterrey, Mexico meetings of the United Nations (March 18-22, 2002) said that (Paragraph 42) in the context that “a substantial increase in ODA and other resources will be required if developing countries are to achieve the internationally agreed development goals and objective” and:

In that context, we urge developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries …

The meeting also noted “that ODA will still fall far short of both the estimates of the flows required to ensure that the millennium development goals are met and the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product”.

You will also find the resolution re-affirmed at the – World Summit on Sustainable Development – which was held in Johannesburg, August 26-September 4, 2002.

This link allows you to learn about the history of the – The 0.7% ODA/GNI target.

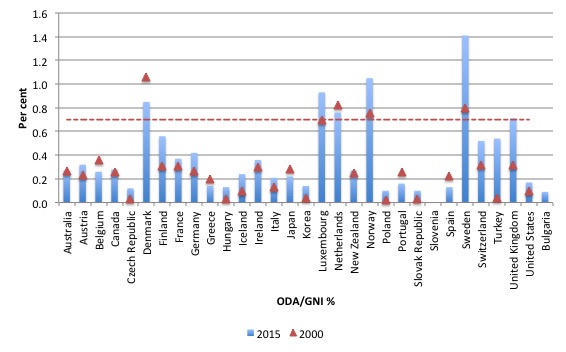

The ODA/GNI ratio tells us how much the government of any country is allocating to ODA relative to the size of the economy (the nation’s total income).

There is a debate as to whether this ratio measures the generosity of a nation given that it doesn’t provide any measure of aid quality nor what happens to the aid once it is dispersed.

The latter point is very important given the extent of the corruption in many nations receiving the ODA and the discussion above relative to global insecurity.

The problem is that ODA remains well below the 0.7 per cent of GNI target and in recent years, under the strain of self-imposed and unnecessary fiscal austerity, the gap has not closed.

On July 16, 2016, the OECD released its latest – Development Co-operation Report 2016 – which shows that:

Net ODA as a share of gross national income (GNI) was 0.30%, on a par with 2014.

The following graphic shows the ODA/GNI ratio for OECD Member Nations (for which comparable data is available) in 2000 and 20156. The 0.7 per cent target is shown by the dotted horizontal line.

The impact of fiscal austerity has clearly reduced the generosity of nations (see Spain, Portugal, Greece, as examples).

The overwhelming conclusion is that there has been little progress in reaching the 0.7 per cent of GNI target.

The outlook is very poor and a new multilateral institution must grasp this challenge to secure greater ODA injections from the wealthy nations.

Conclusion

There are many other considerations that I have not covered in this mini-series. For example, I have not considered funding arrangements, issues relating to external oversight (along the lines of the Independent Evaluation Office that oversees the IMF) and the crucial issue of national independence and accountability.

These will be discussed in later blogs.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976.

37. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

38. The British Left is usurped and IMF austerity begins 1976.

39. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy.

40. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation.

41. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1.

42. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2.

43. The case for re-nationalisation – Part 2.

44. Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future.

45. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 1.

46. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 2.

47. Reducing income inequality.

48. The struggle to establish a coherent progressive position continues.

49. Work is important for human well-being.

50. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 1.

51. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 2.

52. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 3.

53. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 4 – robot edition.

54. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 5.

55. An optimistic view of worker power.

56. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 3.

57. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 4.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Very good. But is there an MMT position on industrial policy?

Especially: industrial policy for the Western world. Or does Bill Mitchell still think we should allow the massive de-industrialisation of the Western world? (as he seems to have does in the past).

If imports are a boon and exports a drain materially speaking then surely

currency depreciation is a bad thing reducing the stuff a people v

can obtain with their national money tokens?

Interesting that a recent book (by a Labour economist and an economist on the Right) tries to put forward a view that exchange rates rather than inflation targets should be focused upon as growth mechanism:

“Ideally, the world should move towards a new

international policy regime that puts exchange

rates centre stage and seeks to maintain exchange

rates at a reasonable level in relation to the economic

fundamentals. ”

Sounds very similar to wast Bill is suggesting above so the beggar they neighbour/zero sum game appraoch can be left behind in the dustbin of history.

Excellent blog post.

i)Call off all debt.ii)As well as purchasing local currency to support exchange rates to maintain low food and energy costs for import dependent nations.They should be given resource support to augment domestic production (which is environmentally sustainable,perhaps even organic urban farming)

And resource support to facilitate energy independence-this will involve global technological research efforts as well.

Hadn’t heard of the Ghana case,how very typical though,”end your market distorting subsidies so we can flood your market with billion dollar subsidy protected agribusiness rice”