It's Wednesday and we have discussion on a few topics today. The first relates to…

Ending food price speculation – Part 1

We are currently finalising the manuscript of my latest book (with co-author, Italian journalist Thomas Fazi) which traces the way the Left fell prey to what we call the globalisation myth and formed the view that the state has become powerless (or severely constrained) in the face of the transnational movements of goods and services and capital flows. We argue that while social democratic politicians frequently opine that national economic policy must be acceptable to the global financial markets and, as a result, champion right-wing policies that compromise the well-being of their citizens, the reality is that currency-issuing governments retain the capacity to ensure there is full employment and can advance the material well-being of their citizens. In Part 3 of the book, which we are now completing, we aim to present a ‘Progressive Manifesto’ to guide policy design and policy choices for progressive governments. We also hope that the ‘Manifesto’ will empower community groups by demonstrating that the TINA mantra, where these alleged goals of the amorphous global financial markets are prioritised over real goals like full employment, renewable energy and revitalised manufacturing sectors is bereft and a range of policy options, now taboo in this neo-liberal world are available. A chapter in Part 3 will concentrate on financial market reforms (what to do with banks etc) and one topic in that context relates to the area of food speculation. We argue that food speculation causes havoc in poor nations and a progressive stance should make it illegal. The enforcement would be through the new institutional framework I outlined previously. In today’s blog I discuss the arguments advanced to justify our position.

I last wrote about this topic in these blogs:

1. Food speculation should be (mostly) banned.

2. We should ban financial speculation on food prices.

The basics

Economics students learn that markets determine prices according to the relative strength of supply and demand. The ‘supply price’ reflects the resource cost involved in producing the good or service, while the ‘demand price’ is the value the purchaser considers applies to the same good and service.

The unregulated market then brings these two ‘values’ together to set the market price and the subsquent quantity that trades. If, for example, at the current price, there are more purchasers than available supply, then the ‘excess demand’ pushes up the price and, vice-versa, when there is an ‘excess supply’ (price is pushed down).

The ‘equilibrium’ is reached when demand is brought into line with supply and thus reflects in the parlance ‘the fundamentals’ of the market.

Prior to the emergence of this modern era of neo-liberalism (‘free market approach’), even orthodox economists realised that there was a case that could be made for government regulation in certain markets to ensure price determination was not distorted.

For example, when the costs of depleting the natural environment (pollution) are not included in the price the supplier offers the product at, then there is a case for the government to force those environmental costs onto the supplier (perhaps via carbon tax), which would then force the price of the product up as it enters the market and discourage buyers.

Without the intervention, the price offered in the market would be ‘too low’ relative to the resource costs involved in producing the product, and the product would be oversupplied.

There are many other situations that have been identified where public intervention into markets addresses so-called ‘market failure’, which refers to cases where the unregulated forces of supply and demand will lead to over- or under-production of a good or service relative to what would be considered ‘socially optimal’.

So even those who operate within the mainstream paradigm have identified that the market can fail to function as the stylised textbook model depicts. This is quite separate from critics who point out there are logical flaws in the way the basic supply and demand approach is constructed. We won’t go into that literature here.

The reality is that pricing is typically determined as a mark-up on unit costs and firms supply up to demand at that price. Further, while the supply and demand sides of the market are strictly independent in the textbook model, in the real world, interventions from advertising manipulate the demand-side to accord with the supply intentions of the producers. There are many other criticisms that can be brought to bear here.

Within the mainstream framework, agricultural markets have certain characteristics that complicate the price determination process. For example, the famous agricultural cobweb model (or hog cycle), is used by economists to explain how supply lags and overshoots in response to demand changes drive prices in a cyclical pattern.

Take the case of a drought, farm supply of a commodity is low, which drives the price up in the current period. Farmers then base next year’s planting decisions on the basis of these higher prices, and the oversupply in the following year, drives prices down. The process continues in the following period when they reduce supply and the price rises again.

The point is that the supply shifts up and down around some stable demand conditions which then traces out a cyclical pattern of prices, that resemble a cobweb pattern.

There are various possible patterns that might occur depending on whether these lagged responses, which lead to the under- or overshoots get bigger or smaller, at each subsequent period. The conditions that govern this result are beyond this discussion.

But the fact that there is a time lag between the planting and production of agricultural products, which drives the possibility that current supply and demand imbalances drive subsequent future supply which then drive a price cycle.

Recognising the problems that these fluctuations would have for farm incomes and consumers, governments have long sought to devise so-called ‘price stabilisation’ policies.

Buffer stock schemes, where the government would determine a preferred price (to stabilise incomes and/or keep food at affordable prices) and then stand ready to purchase any output in excess of that which the market would require to sustain that price or sell from previous buffers output where the supply into the market was below that required to sustain the preferred price.

The Job Guarantee idea was devised as a derivative application of this approach.

There is a huge literature on price stabilisation policies, which we do not need to address here. But it has long been thought that there were major advantages in smoothing out price fluctuations in agricultural markets.

For one thing, the idea of allowing a free market to determine the price is highly problematic in the case of food relative to say the market for digital phones. At a pinch, we can avoid purchasing a phone if prices are what we consider to be too high.

But in the case of food, we have to eat on a very regular basis and so the ‘market’ model that constructs price variations as being a socially optimal balancing of supply and demand is deeply flawed.

Mainstream account of speculation in agricultural markets

The reference to agricultural market fundamentals previously relates to the traditional arguments justifying the efficiency of speculative behaviour.

Accordingly, in mainstream financial economics textbooks (or agricultural economics books) you will read that speculation enhances the market fundamentals (demand and supply).

How does that happen?

Futures markets have developed to provide insurance for the farmers to smooth prices.

So, take the case of a farmer who is to deliver a crop to a market at some future date and is unsure what the ‘spot’ price will be at that date. All that he/she knows is that if the price is below some amount per unit (that reflects their costs, which are more or less known), they will record losses.

The futures markets provides the farmer with a contract to supply a commodity at a given price at some future date. So if the break-even price is $5 per bushel and the future price is $5.50 per bushel then the farmer can be sure of a profit of $0.50 per bushel no matter what happens to the price over the course of the contract.

So the futures contract allows the farmer to hedge against the risk that prices will fall by the time the crop is harvested.

An ‘option’ works in a similar way. The farmer buys a so-called ‘put option’, which might be to sell a volume at $5.50 per bushel at a given future date. If the price is below that when harvest day comes the farmer would exercise the option. But if the price was above the farmer would let the put option expire.

The counter-party to these contracts is the speculator. They are prepared in the case of a future contract to absorb the risk because they form the view that by the time the delivery is made the spot price will be above the agreed price in the contract. So by ‘insuring’ the farmer against risk, the speculator expects to profit by on-selling the commodity to a food processing company.

The buyer of the futures contract, perhaps the food processing company, benefits because they also know what the cost of the fruit input will be into their own product. The hedging certainty helps them make better informed decisions.

As well as providing a hedge against risk to the ‘real’ producer, the future contracts are said to help consolidate a fair price for the farmer. If the futures price rises, then the farmer knows that the expected spot price at the time they expect to bring their harvest to market will be rising and so it is a guide to what contracts they should enter.

In this way, speculation may improve the operation of the real sector. The speculators will tend to buy low and sell high which reduces volitality and stabilises incomes in the sector.

While there is more complexity in the real world, this account essentially captures the conventional view of the involvement of financial markets in the agricultural sector.

However, it is only a small part of the story. In the case of food speculation, speculation has been shown to generate price outcomes that significantly deviate from the market fundamentals (supply and demand).

Why the mainstream depiction is flawed

Food speculation is problematic because as it becomes a significant intervention in the market, the spot prices in the actual market (the physical products) will not reflect the fundamentals of supply and demand.

In these cases, the spot prices are driven by the prices of the future contracts. The spot supply becomes influenced by the temporal structure of prices (the future prices) because these future contracts tell the supplier what buyers are prepared to pay at some later date.

So if the future price is rising relative to the spot price, suppliers will prefer to sell later than earlier. Speculation on the future prices thus drive up both future and spot prices, irrespective of the current demand and supply conditions in the market.

This becomes even more problematic when we introduce the irrational behaviour that financial markets exhibit (the so-called ‘herding’ behaviour). Planning decisions by farmers, for example, become hostage to wild swings in future prices, which undermines the supply chain.

When it comes to ‘food speculation’ we are talking about large investment banks and other financial institutions (such as, pension funds etc) adding the prices of agricultural products to the casino they gamble in.

The important point is that demand for a product in the textbook market model typically requires the purchaser to actually take possession of a physical product from the supplier.

Food speculators do not supply agricultural products nor do they buy them. Their operations involve them trading (buying and selling) the future (derivative) contracts for the products.

Whereas a farmer uses the profits from his/her activity to sustain their operations (that is, via investment in new infrastructure etc), the food speculator does not reinvest the profits they make back into expanding the capacity or efficiency of agriculture.

Speculators do not bring any new money into the sector – for investment in productive capital.

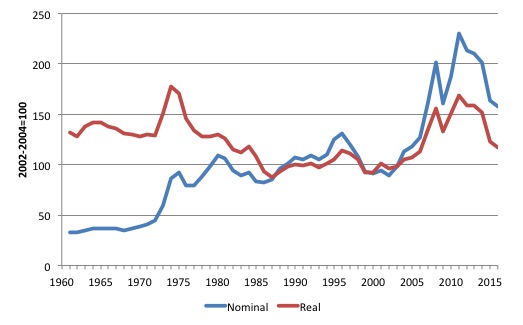

Consider the following graph, which shows the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Food Price Index (FFPI), which is published on a monthly basis and provides “a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices, weighted with the average export shares of each of the groups for 2002-2004.”

The FAO also publishes a number of specific food price indexes (Cereal, Vegetable Oil, Dairy Price, Meat, and Sugar) which the aggregate FFPI summarises.

The full dataset is available HERE. An annual dataset going back to 1961 is available HERE.

The graph shows the annual FFPI from 1961 to 2016. The real FAO Food Price Index from 113.1 in January 2007 to 175.9 in June 2008, a percentage increase of 55.5 per cent.

In the next cycle, between December 2008 (FAO index number 117.8) and December 2010 (Index 180.4) the food price rise was 53.1 per cent.

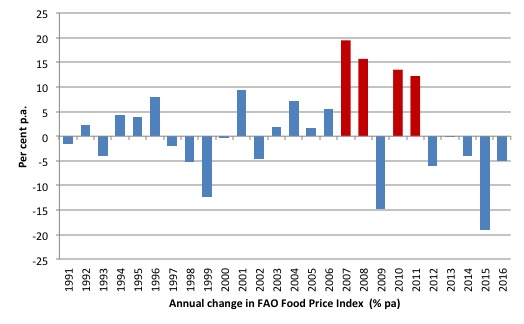

The next graph shows the annual percentage change in the FAO Food Price Index from 1991 to 2016. Clearly, the red columns stand out. So in 2007 the FFPI index rose by 19.5 per cent, then 15.7 per cent in 2008, dropping by 14.7 per cent in 2009 as a result of the recession, and then rising 13.5 per cent in 2010 and by 12.2 per cent in 2011.

The graph hides the extent of movements in the specific components (the five commodity groups) with sugar being more volatile than the other components of the index.

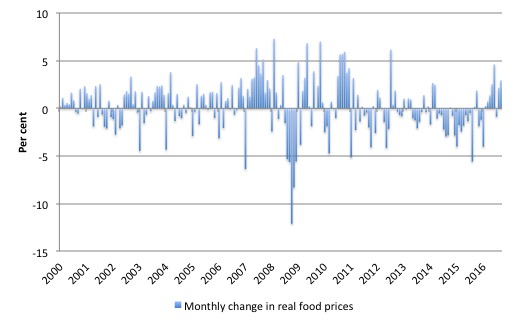

We get another perspective by examining the monthly percentage change in prices for the overall Food Price Index as depicted in the next graph (from February 2000 to April 2011).

So how do we explain those sudden and huge price jumps?

The rapid serial escalation in prices (starting around April to May 2007 and finishing in April 2008) followed by a serial plunge in prices is a classic sign that commodity price manipulation was involved.

Some might argue that these movements were just the operation of the cobweb cycle discussed earlier.

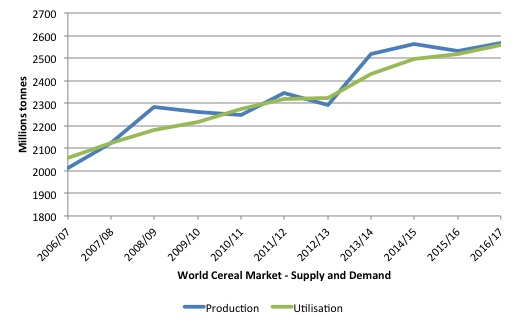

Take the example of the cereals market (which includes wheat and rice). The FAO publish deta

The Cereals Food Price Index, which is a subset of the overall FFPI, rose from 118.7 in January 2007 to 208.5 by June 2008, a rise of 73.7 per cent.

Was there a problem with the production and supply of cereals that could explain that sort of price increase?

The following graph uses the FAO Cereal Supply and Demand dataset.

It show annual production (which is slightly different to supply that there are stored stocks carried over) and utilisation (a measure of demand) for cereals in world markets from 2006/07 to 2016/17 in millions of tonnes.

The data shows that cereal production was remained robust and moved in proportion to the actual demand for the physical product. The escalation in prices around 2007 and 2008 could not thus be explained by farm shortages or a dramatic shift in demand.

Marco Lagi and colleagues that the New England Complex Systems Institute in the US studied a range of proposed causes of “these dramatic price changes” which “have resulted in severe impacts on vulnerable populations worldwide” including (Lagi et al, 2011: 2):

(a) weather, particularly droughts in Australia, (b) increasing demand for meat in the developing world, especially in China and India, (c) biofuels, especially corn ethanol in the US and biodiesel in Europe, (d) speculation by investors seeking financial gain on the commodities markets, (e) currency exchange rates, and (f) linkage between oil and food prices.

They concluded that (Lagi et al, 2011: 1):

… the dominant causes of price increases are investor speculation and ethanol conversion

[Reference: Lagi, M., Bar-Yam, Y., Bertrand, K.Z. and Bar-Yam, Y. (2011) The Food Crises: A quantitative model of food prices including speculators and ethanol conversion’, arXiv:1109.4859, September 21. LINK]

They argue that while “commodity futures markets were developed to reduce uncertainty by enabling pre-buying or selling at known contract prices … ‘index funds’ that enable investors (speculators) to place bets on the increase of commodity prices across a range of commodities were made possible by market deregulation” (p.2).

The evidence is clear that these investors “who do not receive delivery of the commodity” have significant impacts on the spot prices for food.

In other words, the speculation on food prices distorts the market so much that the spot food prices no longer bear any relation with the real price of food or the supply of food.

A 2011 study by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (UNCTAD, 2011) found that “the so-called efficient market hypothesis (EMH)” (p. vii), which claims that prices in markets reflect the supply and demand fundamentals:

… does not apply to the present commodity futures markets

They found that (p. vii):

… the activities of financial participants tend to drive commodity prices away from levels justified by market fundamentals, with negative effects both on producers and consumers.

[Reference: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2011) Price Formation in Financialized Commodity Markets, United Nations, New York and Geneva, June. LINK]

Prior to the deregulation of food markets in the US, which began at the turn of this century, future markets for agricultural products were used in the way I explained earlier – to provide certainty in delivery price.

But when investment opportunities began to evaporate after the dotcom investments turned sour in 2000 and the real estate market crashed in 2007, which segued into the GFC, the likes of Goldman Sachs and others turned their attention to speculation on food commodity indexes.

In a Harper’s Magazine article (July 2010 issue) – The Food Bubble: How Wall Street starved millions and got away with it – Frederick Kaufman provided a detailed analysis of how Goldman Sachs manipulated food prices via the creation of its Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) and caused starvation in the poorest nations.

[Reference: Kaufman, F. (2010) ‘The Food Bubble: How Wall Street starved millions and got away with it’, Harper’s Magazine, July 2010. LINK]

Economist Jayati Ghosh (2010: 74) concluded that:

It is now quite widely acknowledged that financial speculation was the major factor behind the sharp price rise of many primary commodities, including agricultural items during 2007 and the first half of 2008. Similarly, the subsequent sharp declines in prices were also related to changes in financial markets, in particular the need for liquidity to cover losses.

[Reference: Ghosh, J. (2010) ‘The Unnatural Coupling: Food and Global Finance’, Journal of Agrarian Change, 10(1), 72-86. LINK to Working Paper Version]

[to be continued …]

Conclusion

In Part 2 of this blog topic I will trace the problem to financial market deregulation and the creation of the speculative food price indexes.

We will consider the impacts of that speculation on movements in these indexes has had and recent developments, which provide some hope that a complete ban on commodity speculation of this type can become a reality.

Certainly, from a progressive perspective, there should be not price speculation that renders spot prices divergent from the actual supply and demand for the commodity.

Further, there is a clear need for a restructured international framework (replacing the World Bank etc – see links below) to develop and institution that resolves food poverty once and for all.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976.

37. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

38. The British Left is usurped and IMF austerity begins 1976.

39. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy.

40. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation.

41. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1.

42. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2.

43. The case for re-nationalisation – Part 2.

44. Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future.

45. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 1.

46. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 2.

47. Reducing income inequality.

48. The struggle to establish a coherent progressive position continues.

49. Work is important for human well-being.

50. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 1.

51. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 2.

52. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 3.

53. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 4 – robot edition.

54. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 5.

55. An optimistic view of worker power.

56. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 3.

57. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 4.

58. Ending food price speculation – Part 1.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The real problem is that the speculators are the ones bringing in enough money that they can afford to buy the politicians that will get laws passed to benefit finance. Who cares if people starve, the financiers need to make money.

“There is a crucial distinction between Traditional Speculators and Index Speculators:

Traditional Speculators provide liquidity by both buying and selling futures.

Index Speculators buy futures and then roll their positions by buying calendar spreads.

They never sell. Therefore, they consume liquidity and provide zero benefit to the futures markets.

Index Speculators provide no benefit to the futures markets and they inflict a tremendous cost upon society. Individually, these participants are not acting with malicious intent; collectively, however, their impact reaches into the wallets of every American consumer.”

Testimony of

Michael W. Masters

Managing Member / Portfolio Manager

Masters Capital Management, LLC

before the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

May 20, 2008

It would be nice to have this analysis applied to the UK situation since the referendum vote. The recent food price increases in the UK, about 85% of which is obtained from the EU, have been substantial. So far, this rise has been solely attributed to the fall in the pound against the Euro, which has no doubt had an effect. But I have to date seen no discussion of the influence of speculation in this area. I can’t believe speculators stayed away, especially since a Unilever manager said in June that price rises might be on the cards in the case of Brexit.

Hammond has not given much indication what he will say in the Autumn statement other than to say that he will invest in “productive industries”, whatever that might mean. So, the only change from Osborne seems to be no extra cuts. But then, no roll-back apparently at all, even though May’s Downing Street steps speech indicated otherwise (which I didn’t believe). And, of course, no indication from Hammond of any action on the rise in food prices at all, which I don’t expect anyway. What a shower.

Postkey: Business schools teach their students that this is good practice! Businesses don’t seek the common good they seek profit any way they can make it. Only law (enforced) constrains this behaviour.

Excellent piece. Clearly we need to end speculation. Would one way of achieving this be allowing only operators who actually hold stock of the products they are speculating with to create these futures contracts and derivatives?

Really interesting that Bill.

Is a general tighter regulation of market speculation an absolutely necessary piece of the MMT/job guarantee puzzle ?

Looking forward to the book.

As a farmer I can say that most other farmers I know are very wary of these markets. Many embraced them at first, however they are like gamblers now, you only ever hear of their wins. If these markets were only limited to farmers would that not stop market manipulation and fulfill the original purpose of their creation? To me its just another sign of the masses of funds flooding financial markets, meanwhile most people in the developed world have no savings and those in the less developed world are exposed to food shortages. Another point of manipulation are the crop reports that determine market responses, most farmers treat these with suspicion, they are very easily manipulated market intelligence.

Hi Bill,

I was wondering if you could answer some questions about the e-book versions of your upcoming publications, both the intermediate version of the MMT textbook and the progressive manifesto. The MMT textbook, which I believe you self-published through Amazon, doesn’t appear to have features such as reflow, where the text adjusts to the size of the screen you’re reading it on. Your other books, which are available on Google Play do. The lack of this feature makes reading the textbook a somewhat sub-optimal experience on smaller screens, so I was wondering what your plans were regarding the publication of your next books? Is the lack of reflow a limitation of the Amazon self-publication platform? Looking forward to the book as well.

“The recent food price increases in the UK, about 85% of which is obtained from the EU, have been substantial. ”

Which food price increases are these? CPI results this morning show a drop for the food price element. It’s the usual culprits of hotels and transport shoving the value up.

‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages: overall, this group made a small downward contribution to the change in the rate. A more pronounced effect was seen for food, with prices falling by 0.3% between August and September 2016, compared with a rise of 0.1% a year ago. This was due to a combination of smaller downward effects across a range of food items. ‘

Dear Damienb and others who have enquired (at 2016/10/18 at 9/26 am)

The introductory MMT textbook was published through Amazon because we had to get it available by the start of the first Australian teaching semester in 2016 to satisfy new rules relating to compulsory textbook use in courses. It was not our preference but served that purpose.

The next edition, which will include the two-year sequence with many additional chapters and topics within chapters will be published sometime in 2017 by Macmillan Palgrave. We have signed a publishing contract and the manuscript is approaching completion. So it hopefully will be available through Macmillan in the first half of 2017.

Given they are a high-class publisher, I expect all the versions (book, ebook etc) to be first class productions.

I hope that helps.

The other book I am just completing will be published later this year or early 2017 by a well-known publisher. I am not able to disclose their name yet as contract details are not finalised.

best wishes

bill

Neil, I wouldn’t believe the CPI figures entirely. Look at your own shopping. Let me mention just two things — packaged lettuce and women’s clothes. The items have decreased in volume or quality while the price has remained almost unchanged. This is a hidden price increase, practices which have been going on for some time.

Quote:

larry says:

Monday, October 17, 2016 at 21:41

“It would be nice to have this analysis applied to the UK situation since the referendum vote. The recent food price increases in the UK, about 85% of which is obtained from the EU, have been substantial. ”

.

I wondered if Larry was referring to the Tesco-Unilever standoff (“The Marmite Wars”!).

I can’t say I’ve noticed any increases myself, but I will keep my eyes peeled.

There are bound to be fuel-related increases in due course, even for non-imported products.

I imagine there will be a certain amount of profiteering and opportunism going on as well. 🙁

Bill,

This looks eerily like the wool price reserve scheme, which devastated Australia’s wool industry when it collapsed in the late 1980s. How would you prevent such a collapse with food prices?

great blog post

@postkey v interesting