It's been a week of grand fiscal statements. Tuesday, it was for Australia as I…

A lying government pushing economy towards recession and greater inequality

It is highly surreal listening to radio/TV commentators talking about government financial affairs (fiscal balance etc). These so-called experts are paraded before the nation and the script is generally the same. The interviewer who knows virtually nothing but has the key triggers on hand (‘budget repair’, ‘ratings downgrade’, etc ad nauseum) asks the ‘well respected expert’ about the state of affairs and the answers are always the same – fictional. This charade plays out almost daily but reaches a hysterical fever pitch at the time the Government releases its annual fiscal statement (May) or its Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (December). The Government plays along with the charade releasing what it deems to be cleverly crafted documents, shifting revenue and spending across year lines to give one impression or another of the state of affairs. None of the charade is based on any fundamental economic understanding. None of it means anything other than a demonstration of a national scam to hide the truth from the ordinary citizen who for one reason or another relies on experts to summarise technical detail into meaningful sound bites. The nation then goes about its business in this cloud of ignorance, while the elites continue to suppress wages and living standards and march of with increasing shares of national income. They know what is going on and it is in their interests to keep the rest of us from having the same information. It is the same the world over. Well, here is what is going on with a framework that allows the reader to cut through the lies …

Yesterday (December 19, 2016), the Australian Federal Government released its – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook – which “updates the economic and fiscal outlook from the previous budget”.

The MYEFO provides the latest estimates of the fiscal balance out to 2019-20.

The politicians have been frothing at the mouth in the last few days.

I haven’t heard one sensible statement from the governing Liberal coalition (conservatives), the Australian Labor Party (meant to be the workers’ party but essentially conservative) nor the Greens (neo-liberals on bikes).

Each one seems to have a preferred way to meet the same agreed objective for the Federal fiscal balance – “to return to surplus in 2020-21”.

I haven’t heard one commentator actually question why the Federal government should be plotting a course to fiscal surplus, especially when the current account balance is expected to be in deficit (around 3-4 per cent of GDP), households are carrying record levels of debt and consuming cautiously, and private capital formation is at depressed levels.

They all seem to consider the fiscal balance is a goal in its own right, whereas, in reality, it is just like a canary in a mine – it signals the state of the economy.

I have heard the following words, phrases (and variations) used relentlessly in the last week in the lead up to the release of the MYEFO:

1. “the budget deficits will only deteriorate by $10.4 billion.” (Federal Treasurer)

2. On cutting government spending at a time when real GDP growth is negative, “These are important changes that improve the budget position” (Federal Treasurer)

3. We have to stop “borrowing from our children to pay for today’s welfare benefits” (Federal Treasurer)

4. “We continue to be on an improving trajectory to get the budget back into balance as soon as possible” (Federal Finance Minister)

5. “massive cost to budget” (Shadow opposition treasurer)

6. “Danger Zone” (Shadow opposition treasurer)

7. Proposed company tax cuts “simply can’t be afforded” (Shadow opposition treasurer)

8. “The surplus for 2020-21 is wafer thin; it would be blown over in a breeze. $1 billion. The government, if they adopted our plans, could have a better budget surplus in that year because they could drop the company tax cut, they could have negative gearing reform and capital gains tax reform. Instead of being $1bn, the surplus could be about $4bn higher. That would lock in the AAA (credit rating).” (Shadow opposition treasurer)

9. “Repair the budget” (spokesperson for peak welfare lobby group)

10. “we can’t afford not to do it” (business leader talking about cutting fiscal deficit)

11. “We remain pessimistic about the government’s ability to close existing budget deficits and return a balanced budget by the year ending June 30, 2021” (ratings agency comment)

12. “Over the coming months, we will continue to monitor the government’s willingness and ability to enact new budget savings or revenue measures to reduce fiscal deficits materially over the next few years.” (ratings agency comment)

13. “he could cling to his big business tax cut, or he could cling to Australia’s AAA credit rating – and not for the first time Scott Morrison made the wrong choice” (Opposition Finance spokesperson)

14. “while the Government had cut spending, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison had refused to consider revenue measures that would also address the budget deficit.” (Greens Leader)

15. “The Government doesn’t have a plan to ensure that we got the revenue to pay for the services that the country needs” (Greens Leader)

What is a fiscal balance?

None of these statements are applicable as informed knowledge to a discussion about fiscal policy in Australia, where the government issues its own currency, sets the interest rate (via the central bank) and floats the dollar on international markets.

The late American economist Gardner Ackley once said:

My own position on deficits has always been, and remains, that deficits, per se, are neither good nor bad. There are times when they are not only apppropriate but even highly desirable, and there are times when they are inappropriate and dangerous. During a recession or a period of “stagflation”, deficits are nearly unavoidable, and are likely to be constructive rather than harmful.

Please read my blog – A voice from the past – budget deficits are neither good nor bad – for more discussion on Gardner Ackley.

Ackley listed the recessions that he was familiar with (1954, 1960, 1970-71, 1975, 1981-82) and concluded that imposing fiscal austerity during those times “would be prohibitively costly – in jobs, production and real incomes – and perhaps even impossible to achieve on any terms”.

Note he is relating the fiscal outcome to the circumstances in the economy not to some pre-conceived notion that some balance is desirable and another is not.

The reference to a program of fiscal austerity being “impossible to achieve on any terms” is also important. Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

Put simply, the federal fiscal balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the balance is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved.

But to assume that the government can control the balance outcome is to misunderstand the forces that are acting on it.

We know that if the fiscal balance is in surplus then the fiscal impact of government policy settings (interacting with the economic cycle) is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if in deficit we say the fiscal impact is expansionary (adding net spending).

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes.

The reason for this uncertainty is that there are so-called automatic stabilisers operating, which reflect the state of the overall economic cycle interacting with the fixed fiscal policy parameters (tax rates, spending rules etc).

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Fiscal balance = Revenue – Spending

Fiscal balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers because they rise and fall with the cycle in a counter-cyclical pattern.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes (for example, to tax rates), the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the economic cycle.

When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit).

When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the economic cycle by expanding the fiscal balance in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

It also allows us to understand that the ultimate determinant of the fiscal balance outcome in any particular period is the strength of non-government sector spending.

The balance is thus not something that can be controlled by the government and attempts to target a particular outcome as a standalone policy venture is likely to fail.

Governments that impose fiscal austerity with the sole aim of reducing their fiscal deficits (and related public debt aggregates) is likely to reduce economic growth, which in turn undermines government tax revenue and increases its welfare spending, via the automatic stabilisers.

The upshot is that the fiscal balance moves further into deficit or doesn’t move into surplus as planned which then triggers further mindless cutting of net spending under neo-liberal logic.

This is exactly what has been happening in Australia. With the government net spending contribution now undermining national economic growth (as austerity is being pursued), real GDP growth turned negative in the September-quarter 2016 and employment and wages growth have been weak.

The result was that taxation revenue fell by 15.3 per cent in the September-quarter 2016 as real GDP recorded a -0.5 per cent result (Source)

Please read my blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – for background.

The reaction of the Australian government shows how mindless it has become. The federal government is obsessed with achieving a fiscal surplus in the next four years (having pushed out the goal somewhat as annual failures were being recorded – as explained above) – and in the face of a slowing economy with declining tax revenue its response recently was that they would have cut spending even harder.

This fiscal conduct, which continues in the MYEFO is totally inappropriate and dangerous.

Further, once we understand what a fiscal outcome is and what generates it we can further understand that statements such as a ‘deteriorating budget situation’ etc, or eulogising a fiscal surplus per se (or any of the statements I quoted above) become meaningless, and, the exemplar of ignorance.

The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose and achieve full employment.

One of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the non-government sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those non-government decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

That is, ensure there is enough spending to motivate firms to employ all those who desire to work (given public sector employment levels).

The national government has a choice:

1. Maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap.

In other words, the target is not the fiscal outcome but the level of economic activity necessary to achieve full employment – the fiscal outcome will be whatever it is – an uninteresting artifact of responsible government.

It might even be in surplus if the external sector is booming (in surplus) and private domestic saving overall is satisfied. But that would be rare.

2. It is also possible that the government chooses to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) under pressure from employers who desire to keep wages growth suppressed.

This option would mean that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a fiscal surplus will be possible.

But this second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits (via the automatic stabilisers).

It becomes a self-defeating option. In the first case, the deficits might be considered virtuous (good) because they generate high levels of well-being.

Ultimately, a non-government spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs).

But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal outcome will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits would be what I call ‘bad’ deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with ‘good’ deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

Mindlessly thinking that a falling deficit is good and a rising deficit is bad completely misunderstands the role that fiscal policy has to play in the economy.

A 4 per cent deficit as a per cent of GDP might be inappropriate whereas an 8 per cent deficit might be perfect. It all depends on the behaviour of the other sectors, which combine in their spending and saving decisions to determine the fiscal outcome.

In the current debate the commentators have become fixated on the rising fiscal balances rather than the underlying causes – the decline in economic activity (negative in the September-quarter 2016) and the rise in unemployment.

If the commentators discussed the latter with as much urgency and vehemence as they promote the former, then their concerns would soon evaporate because governments would realise the role they have to play in promoting high levels of employment.

However, by exercising their obsession about the fiscal balance – as an end in itself – they pressure governments to introduce pro-cyclical fiscal shifts (austerity) which not only ensure that unemployment rises but also almost guarantees their primary target will also move further away from their goals.

These principles should condition the way you react to the statements in the economics and financial press and the statements from politicians about fiscal policy.

All the quotes I provide above are nonsensical and create a destructive environment which supports austerity. The main point of difference between the major political parties is not about the validity of the whole fiscal construction but rather the degree of austerity (pace of contraction engineered) and the cohorts who will suffer either spending cuts and/or tax increases.

The conservatives want to cut spending on programs that impact the most on the lower income and no income groups and hand out corporate tax cuts to their buddies (who fund their political parties).

The Labor Party want to cut more slowly and tax the rich.

The Greens haven’t a clue but think that if they say “tax the rich” enough they will sound progressive and credible, while they spin around and around in circles on their bikes (sorry Greens!).

It seems almost impossible for people to understand the point that fiscal deficits are neither good nor bad but policy choices can be. That is a basic proposition in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Governments should not aim for specific fiscal outcomes but rather, should aim to achieve full employment and price stability. At that point, the recorded fiscal outcome – whatever it is – will be unambiguously good.

But by obsessing about the fiscal balance in isolation and setting up all sorts of rules and traps for governments, the mainstream economics narrative not only creates bad outcomes but leads governments to pursue bad policy.

They are usually still left with deficits and rising debt – both of which are bad – in that context.

To understand why context matters, please read the following blog – MMT Fiscal Principles.

Now is not the time cutting public spending

The Federal government’s fiscal strategy outlined in the MYEFO – and reinforcing its May 2016 fiscal statement – should be seen the light of a weak economy with elevated levels of unemployment and underemployment and increasing inequality.

I don’t intend to analyse the MYEFO statement in minute detail – it doesn’t really deserve that at a macroeconomic level, given how flawed the strategy is.

At the macroeconomic level – the collective as a nation – we all lose as a result of this incompetent and venal display by a failing conservative government.

The fiscal principles that should be followed requires two conditions be fulfilled:

1. The discretionary fiscal position (deficit or surplus), which is net of the automatic stabiliser effects (the cyclical impact on the fiscal balance) must aim to fill the spending gap between the non-government saving minus investment minus the gap between exports minus imports.

If the non-government sector is not willing to spend all its income (that is, recycle the income back into demand) to maintain the current levels of output, then there is only one sector left that can do it – the government sector via deficit spending.

2. When filling that spending gap, the government has to ensure that the non-government saving, import and investment levels are at their full employment levels.

These conditions specify a strict discipline on fiscal policy if the aim is to achieve full employment.

The MYEFO statement fails badly when judged against these conditions. To make matters worse, it doesn’t even consider them in any explicit way.

Not many other commentators or rival politicians seem to understand them either.

The context

The fact is that the Australian economy is hundreds of thousands of jobs short of being at full employment and as a consequence the fiscal stance of the Government has been too biased towards austerity.

Further cuts will push the economy even closer to recession.

There needs to be a greater fiscal deficit to generate higher levels of activity in the economy and more employment given the current spending preferences of the non-government sector.

Here are some summary facts:

- In November 2016, there were 725,300 persons unemployed at an official unemployment rate of 5.7 per cent. This seriously understates the extent of labour wastage in the economy.

- The current participation rate is 1.2 percentage points below its recent peak in November 2010, which means that some 125,000 workers have left the workforce because of the lack of employment opportunities, the majority of which would quickly take jobs if they were offered.

- In November 2016, there 1,059.4 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1,784.5 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed. Remember to be classified as employed by the ABS a person only has to work 1 or more hours per week.

- The underemployed are workers who want more hours of work but cannot find them. On average they desire an additional 14.3 hours per person. The current underemployment rate is 8.3 per cent.

- The total estimated labour wastage in Australia – taking into account unemployment, hidden unemployment and underemployment – is well over 15 per cent of the available labour force. For teenagers the equivalent figure is a over 40 per cent.

- Even at February 2008, the broad labour underutilisation rate was close to 10 per cent, which means the economy wasn’t at full employment then.

- Real GDP growth was negative in the September-quarter 2016 and has been slowing down all year.

The conclusion we reach based on current non-government spending and saving behaviour is that the fiscal deficit is too small, probably by around 1.5 to 2 per cent of GDP.

Lies abound in the MYEFO

The strategy to get back into fiscal surplus by 2020 is predicated on two lies: (a) that the austerity being pursued will not undermine growth; and (b) that growth will suddenly turn positive again and almost double of the next few years.

Annual real GDP growth was 1.8 per cent in the September-quarter 2016 and had turned negative in that quarter (Q-on-Q). The Treasury is forecasting a return to steady 3 per cent growth by 2018 and close to that next year (2.75 per cent).

How is that going to happen when wages growth is at record lows, business investment is negative and not likely to improve soon, the external sector is undermining growth (via the Current Account deficit), household spending is cautiously moderate and the public sector is contracting?

Add in the declining terms of trade forecast over the next several years, a housing boom that is cooling rather quickly (with attendent consequences for the construction sector) and the fact that by the end of next year the entire car manufacturing industry will have finally closed.

It is quite likely that real GDP growth will fall well below 1.8 per cent over the next year or so without any expansionary policy shift.

How is the fiscal balance going to move towards surplus (and achieve it in 2020) if real GDP growth is significantly more moderate than the government has been forecasting?

Answer: it is not going to move that way and by attempting to pursue that goal the government will further undermine real GDP growth and employment growth.

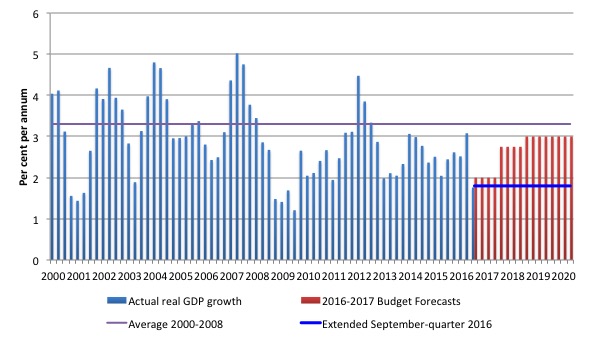

The following graph shows the recent history of real GDP growth. The trend line (at 3.3 per cent) is calculated as the average annual growth rate between the March-quarter 2000 to the March-quarter 2008. In general a trend growth rate between 3.25 and 3.5 is found for Australia no matter which reasonably long growth sample you select.

The blue horizontal line is the extrapolated growth rate as per September-quarter 2016 (the most recent estimate) and is likely to be an optimistic outlook over, at least, the next 12-24 months.

The September-quarter 2016 growth was actually negative and the economy is biased towards that outcome into the immediate future, at least.

The red bars are the real GDP forecasts in the MYEFO out to 2019-20.

If the Government’ forward estimates are correct, then it is accepting that its policies will only generate below trend growth for the next three years at least.

It should be remembered that even when the economy was growing at the (purple) trend there were still high rates of labour underutilisation. Even at the peak of the last cycle (February 2008), the sum of unemployment and underemployment was around 9.9 per cent.

So this is a very mediocre aspiration for the Government to adopt. Moreover, there is nothing in the fiscal statement that would justify the optimistic increase in real GDP over the next few years.

There is every reason to expect, especially with the fiscal contribution to growth declining and business investment is forecast to be sharply negative or static over this period, that the economy will labour on at well below trend rates of growth, given the developments in China and elsewhere.

Certainly the Reserve Bank of Australia is more concerned about the persistence of below-trend growth rates than the Government (the Treasury) seems to be, even though it does not have the effective policy tools available to do anything about it.

The fiscal statement shows that the Australian government (and the Treasury) are jettisoning their responsibility for growth despite hiding behind its political mantra of “jobs and growth”. That message is a total joke.

The point is that the economic cycle is not overheating or even heading upwards. If anything a further slowdown would be expected.

In that context, running a contractionary fiscal position is irresponsible and the anathema of good policy.

The private sector’s debt position is set to worsen

The economic predictions, which underpin the fiscal statement and are contained in Part 2: Economic Outlook, show that the Treasury is forecasting the following outcomes:

1. The fiscal deficit was -2.4 per cent of GDP in 2015-16. They project it will fall to -2.1 per cent of GDP in 2016-17, then -1.6 per cent (2017-18), -1.0 per cent (2018-19) and -0.5 per cent (2019-20).

2. The current account deficit which was 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2015-16, will suddenly contract to 1.25 per cent in 2016-17, then stabilise at 2 per cent of GDP after that. Those predictions are fanciful. The Terms of Trade at present are high but will not remain so.

I note that the average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2015-16 has been -3.9 per cent of GDP. So we might consider that sort of performance to continue over the fiscal projection period. There is certainly no expectation that the current account will suddenly record the outcomes assumed.

So what does that mean in terms of the sectoral balances?

Remember that we can derive a relationship from the national accounts between spending and income for the three-major sectors in the economy: (a) the external sector; (b) the private domestic sector; and (c) the government sector. (a) and (b) sum to be the non-government sector.

The sectoral balances must hold as an accounting statement and we then need to interpret their evolution by understanding what drives the individual balances.

Please see – Answer to Question 3 – for the complete explanation of the sectoral balances approach and derivation.

The final sectoral balances expression that results from that derivation is that:

(S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

where S is private domestic saving from disposable income, I is private domestic capital formation investment, G is total government spending, T is government taxation receipts, and the CAD is the current account deficit (the trade deficit plus net income transfers abroad).

The sectoral balances equation is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

This allows the private domestic sector to save overall (which is different from household saving out of disposable income denoted S above). That means, the private domestic sector is spending less than its total income and building wealth in the form of financial assets.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T less than 0) and current account deficits (CAD less than 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

The previous expression can also be written as:

[(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

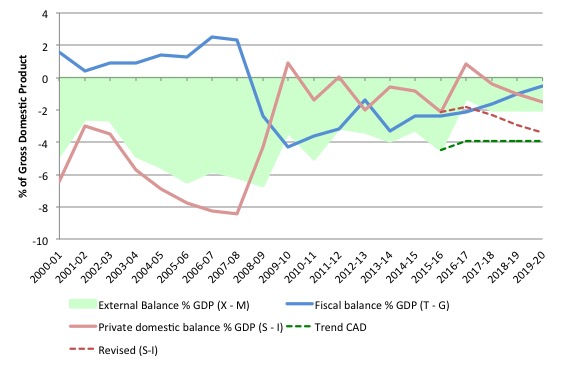

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2019-20, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in the MYEFO.

I have used two projections of the external account:

1. The MYEFO actual projections as noted above (captured by the green area right of the vertical black line – which demarcates the point in time between actual and projected).

2. The average current account position since the 1973-74 – that is, a deficit of 3.9 per cent of GDP.

Correspondingly, I computed two balances for the private domestic sector conditional on the MYEFO fiscal estimates and the two different external assumptions:

1. The balance implied in the actual MYEFO projections – the red line after black demarcation line.

2. The balance that would arise if the external deficit was around its long-term average (a more realistic assumption) – dotted red line after black demarcation line.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

Even with the unrealistic MYEFO assumptions about the external sector (and real GDP growth), it is clear that the current government strategy is consistent with pushing the private domestic sector into higher indebtedness.

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09, which saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit – not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to move towards rebalancing its precarious debt position.

The fiscal strategy now being pursued by the Government and reaffirmed in yesterday’s MYEFO now implies as the graph shows that the private domestic sector will once again be accumulating debt as it progressively spends more than its income.

With investment flat, the debt would fall onto households, who are already carrying record levels of indebtedness.

We are on the path back to the excessive private domestic debt levels that prevailed before the GFC.

Under the more realistic external assumptions (dotted lines), the increase in private domestic indebtedness will be even more marked.

But, then you examine the other fiscal projections in Table 2.2 of the Economic Outlook 1 and the outlook for household consumption and dwelling investment are fairly constant or falling (dramatically in the case of homeinvestment).

The MYEFO also suggests zero growth in business investment for 2017-18 following a decline of 6 per cent in 2016-17.

So the question then is obvious – where is all the private domestic sector spending implied by the sectoral balances analysis going to come from?

The answer is also obvious: the Treasury estimates are inconsistent. They do not add up. Which would not be the first time that observation has been apparent.

In other words, the fiscal estimates provided by the Government are concocted in an ad hoc manner which little recognition of the underlying relationships that have to hold between the three macro sectors.

If the projections are to be believed then the Government is expecting the private domestic sector to maintain the growth in the economy by increasing its indebtedness.

That would mean we are heading in the same direction as before the crisis – growth becomes reliant on private debt buildup.

The whole nation is transfixed on fears that the government debt in Australia is too high – courtesy of all the scaremongering that has been going on.

But nary a word gets mentioned about the dangerous private debt levels. It is true that most of the debt is owed by higher income people in Australia, which makes an insolvency crisis of the likes of the sub-prime less likely here.

But the reality is that the debt levels and the growth in them (about the same as disposable income) means that consumer spending is likely to remain fairly subdued overall.

It is unlikely we will see a return to the pre-crisis period when debt grew much faster than disposable income and the resulting spending maintained stronger economic growth.

It is thus likely that none of the projections in the MYEFO will be realised and the strategy of ‘fiscal consolidation’ is just made up to satisfy ideology.

Another way of saying that is that the Government is just lying.

Conclusion

The MYEFO is now offer and thanks be for that.

Xmas is coming and the talk of fiscal emergencies and all the rest of the nonsense will be forgotten in the sparkle of the tinsel.

But what we can conclude – categorically – is that this lying government is fiscally irresponsible and is driving the economy towards recession and greater income inequality.

That is its present! to the nation to mark the end of the year.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

V good overview of a problematic economic policy being pursued by almost all advanced economies. Low growth accepted with ref to falling productivity and worsening demographics. As mentioned, unemployment of up to 15 % and youth unemployment of 40 % is a shame. Would like to replicate your excellent overview on Scandinavian countries, where surplus ideology is equally strong. Have you looked into their balances? Or any other sources where this have been attempted. Also, would like your views on recent OECD economic outlook, where they seemingly take a more fiscally expansive position, incl. advocating debt financed public investment. And, happy new year; looking forward to more posts and the book on labor parties and economic policy.

brilliant as usual bill.

old habits die hard, and since hockey , heck since costello , governments have been rolling the dice on the capital account and bank balance sheet expansion saving their bacon.

that jig will surely be up over the next 5 years, and we should have our proof of whether banking system money is neutral or not.

all the hubub over our credit rating by the mainstream media. just thinking outside the square, im thinking increased borrowing costs might just be the tonic to force the government into a corner and take a fiscal trajectory you have outlined.

as much as i have total contempt for ratings agencies, they might do us a favour.

i think the budget numbers are going to blow out over the next 5 years and both parties will have no choice but to countanence a paradigm shift. they wont have a choice care of the unemployment rate and the household balance sheet especially in those mortgage belt electorates that decide elections in this country

as you suggest budget deficits moving toward 4% of gdp are required to stabalise the situation.

i bump into the odd government advisor or two in my daily travels, and when you try and explain how their accounting wont stack up because of the heroic assumptions they are making about bank balance sheet expansion, the penny has not dropped.

2% nominal, when population growth should give u 1.5% atleast. pathetic . and the treasurer pimping 2% as the new normal, when anything below 3% is a fail given our present circumstances

Does anyone in the MSM ever consult you Bill?

Richard Denniss – who I don’t think understands sovereign money – nonetheless makes a good point here. That is, the coalition are attempting to redefine REDISTRIBUTION of existing spending as “stimulus”. Everything I have ever seen unfortunately leads me to the opinion that this will successfully hoodwink the public into believing that slashing welfare spending and redistributing it to areas where the government has political allies (a) counts as stimulus and (b) prove to them that stimulus spending doesn’t work when shuffling existing dollars around fails to positively impact the overall economy.

This is one of the things that politicians do best – redefine the meaning of things when the actual meaning does not suit their purposes, until the electorate comes to believe it. They succeeded in redefining the meaning of “full employment” so that the public now believes that the current appalling situation represents an economy close to full employment. And I suspect they will probably succeed here as well, thus destroying any public perception that stimulus is ever necessary or desirable, by conning the public into believing that stimulating and redistributing are one and the same.

Sorry, don’t mean to be pessimistic but I think that’s what is likely to happen here.

[Bill edited out material from Fairfax press]

I truly believe we (Australia) is beyond hope. I have spent the last 5 years presenting to very senior people in business and politics the accounting realities of our financial system. No-one gets it. I think this is because

1. People associate the 2000-2007 surpluses with good times (not realising it was simply a private debt boom)

2. Treasury is in control of the economic agenda – and too many people in the Treasury have built their entire careers on the benefits of fiscal surpluses. They can’t back-track now. Every time I present to a politician, they fall back to “what does Treasury think”. And of course they think I talk of “money printing nonsense” sending Australia the same way as Zimbabwe.

I have given up. I don’t care any more. We are going to learn our lesson the hard way and I will organise my financial affairs accordingly.

I have been following this post for about 2 years…(not just because you are a musician, although that helps), again, you are the voice of reason and hope in a sea of political stupids!

Bill is trying to use Accounting (which is ex post) to make causal inferences with the word ‘generate’ here…

So there is a problem with Time Domain here…

Hypo govt could start with $10k to every household on the 1st of the month 25% taxable income…

Households turn that over 11 times during the month while accruing income tax payable of 25% for each turn and on the 30th pay $9700 taxes leaving the govt with a “deficit!” of $300 for the month and every household realizing $38k of income for the month … Then on the 1st govt pays each household another $10k …

So income would be $38k for the month and the “deficit!” would be $300 for the month (10,000 – 9700)

so how does the govt sector “deficit!” of 300 ‘generate’ (present tense) the $38k of income if you use a one month accounting period like the govt typically does to determine what “the deficit!” was for the previous month (past tense)?

Its really the original $10k that the govt spent that month that ‘generated’ the income…. and the taxes and any resultant “deficit!” (non-govt savings) is a function of that leading govt spending of 10k not the 300 of ‘deficit’

So like Brazil saying they are going to stick to a 3% deficit could work as long as govt spent enough FIRST and nobody saved very much and you could tune the system to operate efficiently….

Our gov’t (all sides), media (esp the ABC) and economists (Pascoe, Kook, etc) make me sick.

A bit hard (if witty – “neo-liberals on bikes”) on the Greens, Bill. My reading of their position is that a bigger deficit now will lead to a budget surplus later (ie by 2020-21). Regardless of its truth or not, that’s a traditional Keynesian approach and not particularly inconsistent with your own chartalist views.

But as I’ve often noticed – and certainly not just on this issue – once something becomes a bipartisan consensus in Australia then it is quite impossible to get views outside that consensus properly developed and debated in public. Which means that when the punters finally notice that the official consensus is not actually in their interest, they tend to turn to people who appeal to their instincts rather than their reason – like Trump.

@Leftwinghillbillyprospector: I think its even worse than they suggest as the well off have lower propensity to spend than those on low income. But it could be an exercise in shoring up their political base?

@Barri Mundee: I think there’s probably a multi-pronged motivation here, one if which is likely shoring up their political base (I hear rumours that the coalition is getting ready to split, led by Cory Bernardi and One Nation looks to be gaining strength, capturing right-wing voters who have become despondent with the coalition).

I can’t see where it can help them much in the longer term (but then, politics here is about pretty short term stuff). As you say, those on lower incomes have a higher propensity to spend their entire income. Money spent on welfare doesn’t just evaporate into the ether simply because it was given to people that the government keeps conditioning the electorate to despise. I think people often imagine that money “wasted on dole bludgers” as the government wants us to think of the unemployed, is somehow destroyed because it was spent “wastefully”. The facts would be that much of it goes straight to the coalition’s traditional support base – business, small, medium and larger – as welfare recipients spend it on food, clothing, rent etc. Ever seen a grocer say to an unemployed person “hang on, you’re a welfare bludger – I’m not selling (accepting money from) to you”. No, nor have I. Squeezing welfare recipients would simply reduce the cashflow to significant numbers businesses operating where significant numbers of welfare recipients exist.

hi bill,thanks for your blog – i am gradually digesting your article,the argument and strategies you lay out strike home to me.i have been grappling with the concept of austerity for some time … austerity really is the failier of politics