It's been a week of grand fiscal statements. Tuesday, it was for Australia as I…

Austerity is the problem for Britain not Brexit

Regular readers will know that I firmly supported the LEAVE vote in the British referendum in June 2016 even though that was somewhat gratuitous given I am neither a British citizen or live there. It was one of those academic exercises where we wax lyrical with little personal at stake. But that aside, if I had have been a British citizen then I would have voted to leave without doubt. The Internet links us more closely these days and in before the Referendum vote I received heaps of antagonist E-mails informing me that I was bereft of all credibility in taking that position. After the vote, when I dared to point out that the official (Bank of England, Treasury, IMF, OECD) and non-official predictions (the investment bankers etc – remember Credit Suisse sending out a Mayday alert of an impending recession which would wipe out 500,000 jobs!) were over the top to say the least (given the post-vote data), I was called delusional and worse. And these personal attacks came mostly from those who claim to be on the progressive side of the debate. Spare the thought! Subsequent data has indeed pointed out that none of the predictions of doom have so far turned out to be true. I know there might be longer term issues when they get onto working out the detail but I stand by my view – Brexit – if handled correctly by the British government will be a net benefit to the nation and its democracy. If not it could offer no real gains. But in this smokescreen of misinformation, a serious study from Cambridge University researchers – The macro-economic impact of Brexit – has concluded, that while there might be some short-run losses in GDP per capita, they soon recover as the British economy adjusts to its break from the dysfunctional European Union. There is no disaster scenario forthcoming! To the de

I wrote about Brexit in the following blogs (in chronological order recent to past):

1. The British reality defying the ideologically-based gloom and doom (November 29, 2016).

2. Mayday! Mayday! The skies were meant to fall in … what happened? (August 24, 2016).

3. Growth outlook deteriorating – and don’t blame the Brexit vote (August 1, 2016).

4. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation (July 13, 2016).

5. Why the Leave victory is a great outcome (June 27, 2016).

6. Britain should exit the European Union (June 22, 2016).

Remember this headline from July 14, 2016 – CREDIT SUISSE: ‘Mayday! Mayday!’ – Britain’s impending recession will kill nearly 500,000 jobs.

This headline was typical of the hysteria that surrounded the Referendum vote. In the context of the current storm about whether Russia hacked American computers (of course they did, probably at the same time America hacked Russian computers)

The British Treasury released two reports in 2016 covering its estimates of the impact of a Leave vote:

1. HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives (released April 18, 2016).

2. HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU (released May 23, 2016).

The problem was that the estimates in the HM Treasury analysis were ideologically-biased and lacked any real basis. Anyone with an understanding of the way monetary systems work would have been able to see through their analysis.

Some couldn’t obviously. Others, seemingly, ignored the spin – perhaps without really knowing whether it was sound or not. Other things mattered to those voters.

The HM Treasury disclose in its long-run analysis that its results are derived from applying its own projections to the NiGEM model:

All the elements of the analysis are brought together and combined in a global macroeconomic model maintained by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and used by the IMF, OECD, Bank of England and others. The model is used to assess the overall macroeconomic impact on the UK (and the EU) under the different alternatives in the long term.

In the ‘immediate impact’ analysis, they also use NiGEM (the NIESR General Equilibrium model), which is used “by over 40 organisations including the IMF, the OECD, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank” … and HM Treasury!

You get to see how Groupthink operates.

1. The NIESR start off with a New Keynesian style, Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model, which as I wrote last week in this blog – Mainstream macroeconomics in a state of ‘intellectual regress’ (with links to earlier discussions about DSGE) is a framework that is incapable of saying anything really meaningful about the real world.

NiGEM “has many of the characteristics of a … DSGE model” (Source)including the use of rational expectations (model consistent. Translation: This just means they have to conform to a long-run solution that is supply-determined. But you need to understand the ‘supply-determined’ bit is just imposed by their ideological view that money doesn’t matter in a long-run general equilibrium. The standard nonsense, that is.

They impose various restrictions on the parameters in the model “to ensure that the model delivers a unique NAIRU … This is consistent with the finding by … Mankiw … and others”. Translation: they claim the model is data-consistent but really they just make it that way with various fudges so that they can then claim the data is consistent with the NAIRU fairy story and long-run monetary neutrality.

Firms are profit-maximisers and set employment according to the marginal product of labour. Translation: standard neo-classical nonsense that fails to grasp the interdependence of the supply and demand sides. Wages are an income (demand) and cost (supply). Cutting real wages in their model increases labour demand. In the real world, if such a cut can be engineered, it will probably reduce labour demand because sales fall with lower incomes.

The NIESR say that “In all policy analyses we use a tax rule to ensure that Governments remain solvent in the long run”. Translation: They impose arbitrary ‘solvency’ restrictions on government fiscal deficits such that tax rates are always increased if the deficit increases beyond some arbitrary solvency threshold (“the target is exogenous by default, so solvency is in place”). (Source).

I could go on. These ‘models’ are fictions (as all models are) but with little linkages to the real world, which makes them unreliable as a guide to what would happen in that world if something changed. All we can say is that in the stylised world of NiGEM a recession or some other calamity will occur. And we can all say to that: Who gives a toss!

2. Moreover, all the usual suspects then use this model – HM Treasury, IMF, OECD, Bank of England and others (over 40 organisations in total).

So, they all gather around the same Kool-aid feeding trough and produce an array of reports that make it seem as though all these different organisations are coming up with the same result on their own – ergo, the conclusions must be correct.

If you believe that you will believe anything really. These exercises are in the same ball park as ‘fake news’.

Same Kool-aid, same poison!

Groupthink is characterised by this inward, self-referential behaviour.

While there ‘long-run’ analysis is meant to apply out to 15 years (after the exit is formalised), the immediate analysis is over the next year or so (“peak impact over two years”).

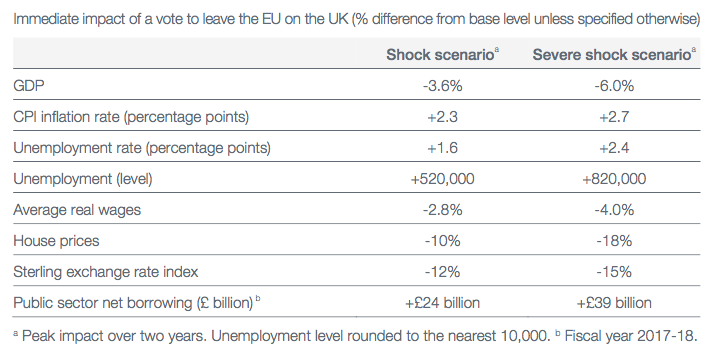

HM Treasury produced these estimates of the Brexit impact under its Shock Scenario and its Severe Shock Scenario, which are differentiated by how “cautious” HM Treasury is about its imposed assumptions.

So think about hitting your head with a normal hammer (it will hurt) and hitting it with a sledge hammer (it will hurt more). And while you are doing that don’t question why you would be hitting yourself on the head with any form of hammer in the first place.

That is the game they play. They assume an array of bad things – plug them into the stupidly-ignorant NiGEM model then compare them with the results of assuming even badder things.

So, of course, “a vote to leave would result in a recession, a spike in inflation and a rise in unemployment” and the rest of it.

GIGO – Garbage In, Garbage Out!

Anyway, the Treasury produced these forecasts (Table taken from their Report):

The Treasury estimates presented in the Table above were complemented by a host of other estimates from other organisations (investment banks, multilateral institutions, etc) – all telling the same story. Doom from the outset and getting worse.

The Cambridge Study uses a different modelling approach (the CBR macro-economic model) (Working Paper 472), which was developed post-GFC to address the fact that the existing DSGE and variant models:

… failed to forecast this unprecedented failure of the economy … the failure of forecasters to warn that a collapse was even likely given the huge previous build-up of debt in the household sector and more particularly within banks … Moreover, almost all UK models then over-predicted the post-2009 recovery. They also under-predicted inflation, which rose to over 5% in the midst of recession, and failed to foresee the rise in employment as the economy stagnated after 2009.

A comprehensive failure you might say.

The Cambridge researchers (Graham Gudgin, Ken Coutts and Neil Gibson) from the Centre for Business Research conclude from this that:

This catalogue of failure suggests that something is badly wrong with the state of forecasting models.

And like all those trapped in Groupthink:

The modellers themselves appear to have shrugged off these failures …

So business as usual – move on.

But:

The forecasting failures however have a cause in an emphasis within conventional models on supply-side factors, in face of what has proved to be a large failure of demand.

These failed models all impose ‘long-run’ restrictions – which mean they make up a solution that eventually has to be reached (irrespective) which satisfies their theoretical biases. In this case, they assume away long-run demand effects and conclude that eventually general equilibrium is restored.

They then impose ‘adjustment restrictions’ or ‘policy rules’ that force the adjustment path (short-run dynamics) of the economy to be consistent with where they have forced the model to go when all adjustment is over and the ‘solution’ settles down (after all the effects of the change are exhausted.

As the Cambridge researchers state:

The Government’s OBR model, for example, starts by projecting a trend path for potential output and then assumes that monetary policy will guide the economy toward that path. Any off-path point due to shocks leads to a return to trend within 3 to 4 years. Other forecasters, including the OECD, IMF, and several commercial forecasters, use an approach based on similar principles.

Feeding from the same trough!

The problem is that these models cannot cope with real world events, especially when major demand (spending) shocks occur.

The Cambridge researchers say:

Failures in forecasting of this magnitude exhibited since 2008 suggest that some modesty may be required in guiding future macro-economic policy in the UK. In practice, policy advice has continued as if little has happened. The Government asserts that reducing the size of the government debt must be a key priority if the UK economy is to return to economic health, and that major public spending cuts are required to reduce the debt. There has been relatively little modelling work to investigate whether such a strategy is either necessary or practicable. Indeed the nature of the OBR model (and similar OECD and IMF models) means that they cannot be directly used to investigate such questions.

So they are just asserted and ad hoc model manipulations are then used to reinforce these assertions.

They also note that:

The academic economics profession is equally unworldly. The mainstream approach is now to use so-called DSGE (dynamic stochastic general equilibrium) models … assuming that market forces will bring the economy back to its full capacity operation subject to certain frictions caused among other things by government regulations. We agree with Keynes’s view that neo-classical ideas are of little relevance to the macro- economic behaviour of real economies in major recessions … Most Central Bank forecasters, including the Bank of England, use a direct DSGE approach with, in the BoE’s case, generally poor results.

So the Cambridge approach is very different and emphasises:

… the level of output in an economy will be determined by effective demand for its goods and services. There is, in this view, no exogenous long term trend in capacity. Instead capital stock and labour supply (including skills) are endogenous.

In other words, that where the economy goes over time is a reflection of where it has been. A large demand shock can push the economy of its current trajectory onto some other trajectory, which changes things forever.

There is less imposition of desired outcomes (in the long-run) on their model’s behaviour – “there is no explicit NAIRU” (a forced state that all adjustment has to conform to – as in DSGE models).

While I could go on in more detail about this, suffice to say that I have a lot of sympathy for the Cambridge UKMOD approach. It shares many aspects that are consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), whereas DSGE models and their variants share zero commonality with MMT.

The other point the Cambridge researchers make in their most recent paper – The Macroeconomic Impact of Brexit (Working Paper No. 483, revised January 2017) – that Brexit will be a special event and so “no normal forecast is possible”.

They thus construct “construct a series of scenarios based on assumptions about future trading arrangements, migration controls and about the short-term uncertainties which could affect business investment in the run-up to the likely leaving date of 2019”.

They find that (five months after the referendum):

1. “only one of the Treasury’s expectations has been clearly realised. This is the fall in the value of sterling”, which is of a magnitude consistent with the Treasury’s ‘severe shock’ scenario.

2. While the Treasury forecasts for interest rates, housing prices, household consumption, house construction, real GDP have all been proven to be very wrong, “Our own expectation has been that there would be little direct impact of Brexit” on these things.

3. “the long- term impact of Brexit is expected to be well below Treasury estimates, even if the UK ends up with no free trade agreement or other privileged access to the EU Single Market, our expectation of any transitional losses to investment would be relatively small.”

4. On trade, the Treasury said that if Britain “fell back to WTO rules” (that is, lost privileged access to the EU single market) then there would “a loss of trade with EU of 43%”. Overall, given that the EU accounts for around a half of total British trade, the Treasury estimated that Brexit would lead to “a total loss of trade (to EU and non-EU destinations) of 24%”.

I won’t go into detail here on how they reached that specific result (they use so-called ‘gravity modelling”) but the Treasury claimed that British trade has risen by 76 per cent because it entered the EU and that would disappear with no alternative gains once they leave the EU.

The Cambridge research disputes that assumption and approach.

They show that the EU6 share of British exports “peaked at the end of the 1980s at just over 40% and has subsequently fallen back to 30% by 2015”, which makes the 76 per cent loss appear unbelievable or “implausible” to use their word. The Treasury just fudges their result and “provides virtually no information directly about UK trade with the EU”.

They replace the “flawed” Treasury approach with a modelling approach that uses “direct evidence on UK exports to the EU” and conclude that given “average tariffs are so low” to non-EU nations seeking to trade within the EU:

1. “It is not obvious that membership of the EU since 1973 has made any sustained difference” to real GDP per capita. They cite the US experience and its high penetration to the EU despite its non-membership.

2. “The overall impact in the baseline Brexit scenario is that GDP is largely unchanged up to 2020 as the lower exchange and interest rates offset the negative impact of uncertainty.”

3. “per capita GDP … ends up in 2025 at much the same as in the pre-referendum forecast.” In other words, Brexit does not mean (on average) British citizens are poorer.

4. After an initial spike in inflation due to the rising import prices (following depreciation), by 2020, “inflation begins to fall although it does not reach the 2% target by 2025.”

5. “earnings will rise by more than 2% as employment rates reach a peak in 2017 and especially as migration reduces from 2019 … we expect real wages to be broadly flat for the next decade”. A poor outcome but not influenced by Brexit.

6. “Our pre-referendum forecast had unemployment rising back to almost 7% of the labour force by 2025 due to continuing public sector austerity, a downturn in the credit cycle and higher interest rates … Unemployment rises but by much less than previously expected.”

Overall, the Cambridge researchers find that:

The economic outlook is grey rather than black, but this would, in our view, have been the case with or without Brexit. The deeper reality is the continuation of slow growth in output and productivity that have marked the UK and other western economies since the banking crisis. Slow growth of bank credit in a context of already high debt levels, and exacerbated by public sector austerity prevent aggregate demand growing at much more than a snail’s pace.

Conclusion

That really should be the story – the deliberate undermining of growth by government austerity and the behaviour of the zombie banks.

The conservatives (including all the misguided neo-liberal ‘progressives) who are obsessed with the damage that Brexit will cause are just diverting the conversation away from the destruction that their fiscal ideology has caused and is continuing to cause.

Brexit is a smokescreen. It will not be detrimental to Britain in the long-run if the British government takes responsibility and uses its fiscal capacity to focus on domestic growth and employment.

But Britain will suffer if the fiscal austerity mindset continues (with or without Brexit) and the disruptions that will, in the short-run, accompany Brexit will be made worse by on-going austerity.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The debate in the UK has polarised opinion sharply.

The Remain case, in light of no disasters to date, have retreated to an unassailable ‘But we haven’t left yet’ position. Finding the best way forward for the country does not appear to be a concern and so the hammer metaphor is very appropriate.

“We haven’t left yet” is a position that denies any impact of expectations on an economy. It’s even more of a religious position than the one the mainstream take.

Isn’t the NIESR the operation that Portes and Wren-Lewis are associated with? So it’s hardly surprising it’s got ‘Establishment’ written through it like Blackpool rock.

“Brexit is a smokescreen. It will not be detrimental to Britain in the long-run if the British government takes responsibility and uses its fiscal capacity to focus on domestic growth and employment.”

This! This is the reality that 99.9% of economists have lost sight of. This is the only real thing yet they can’t see it with their head in their models. Crazy to watch the mass groupthink stuck in a never ending nightmare that can’t correct itself it seems.

Bill, “NiGEM “has many of the characteristics of a … DSGE model” (Source)” link does not take one to the documentary source for the quote, only the general site.

How the Treasury packaged up their findings for public consumption was particularly devious. It took current GDP and divided it between the number of households in the UK. This appeared to give a current ‘average household income’ of £68,000. Clearly, most households don’t have an annual income of £68,000 and it’s interesting that the Treasury doesn’t use this figure when setting the benefit cap for households (it is currently set at £23,000, which happens to be the true median household income).

If the UK were to stay in the EU then, according to the Treasury model, GDP would rise by 2030 to the point where the new ‘average household income’ would be more than £90,000. And if we left the EU it would 6% less and, according to the Treasury way of framing things, households would be £4,300 ‘worse off’.

Of course, the Treasury wasn’t really saying anything of the sort – it just wanted people to think this was the case. The Treasury decided to frame the calculations this way to create a completely false impression in voters’ minds, one that would sway the vote in favour of Remain, and Ministers went on television to push the £4,300 figure. They did this without mentioning that it was a prediction fourteen years into the future, or that it was arrived at by dishonestly assigning GDP to households and bore no relation to actual household income. The result was that many people imagined that their own household would lose £4,300 pretty much from day one. It’s the sort of deception that goes on all the time, because it’s a very effective way of manipulating opinion to suit political ends.

brexit always seemed like a useful decoy or displacement activity which is to the benefit of the neo-liberal agenda. People wraping themselves in Union Jacks and chanting bullshit such as ‘take back control’ must be music to the ears of the neo-libs because they know that there will be no taking back control, brexit or no brexit.

What is saddening is that neo-liberalism is pushing Europe towards fascism incrementally.

wow the cambridge model is quite sophisticated in that they have really taken on board the ’08 crisis and are looking at credit cyces

” number of loans is low due to banks’ restrictions on the supply of

loans.”

I don’t think their assessment of inflation is right (maybe I’m wrong). It seems too high and prolonged to me. Perhaps they have not properly considered the VAT hike in 2011. The peak inflation of 5% in 2011 was not all devaluation or commodity prices, the VAT hike played a big role in that, and I think oil prices will only rise very slowly from here, as there is plenty of spare capacity.

Both of my children would have voted for remain. Unfortunately only one voted because the other lives in the Netherlands. My Uncle who is retired lives in Spain, he couldn’t vote either. For many people the economic issues are irrelevant but the freedom of movement is essential. Why do you only regard the economic issues as important when these other issues are equally important.

Regarding models, can a model ever tell you to do anything it wasn’t programmed to tell you to do? Appropriate to this can a model which was not programmed with MMT considerations ever give economists an MMT answer?

Surely the model is, or should be, like an hypothesis. It can be anything you like but once it provides output then that output has to be compared with experimental or empirical data. If they don’t match then you have to ditch the model. If they do match then you don’t have to ditch the model yet. i suppose you can get round this by saying Economics is not a science.

Benedict@Large:

A more serious problem comes up, which is, if a model tells you something you didn’t expect it to, does that mean the model has produced novel results, that the model has a design flaw, or that the model has an implementation flaw (i.e., bugs)?

By definition, a computer program will never do anything but what it’s programmed to do (hardware errors notwithstanding), but there’s a world of difference between the reality (the actual code that was written) and the intention (what someone expects to see when they run a program), and modeling of all sorts, including “deep learning,” lives in that gray area. The fact that one can write code that’s more complicated than one’s ability to understand it always leaves open the possibility for novelty, but it’s much trickier to then ascribe epistemic significance to that: you get dangerously close to fully turning modeling into tea-leaf reading.

John,

I understand that many young people saw the EU as something that ‘brought people together’, but I think they were being starry-eyed (pun intended) about the EU. The economic factors (austerity/privatisation of public services/ creating debt slavery) are the dominant ones and, in the end, determine social relationships.

If you think 51% unemployment for youth in Spain/mass emigration from Ireland/3 Million people in greece outside any health care system/young people deserting Portugal in droves is good for young people then it is a strange notion of ‘good.’

Oops, Paul Krugman does it again….he just can not resist it:

“Basically, government borrowing once again competes with the private sector for a limited amount of money. This means that deficit spending no longer provides much if any economic boost, because it drives up interest rates and “crowds out” private investment.”

http://www.alternet.org/economy/paul-krugman-exposes-gops-craven-hypocrisy-deficits-and-why-it-matters-more-ever

If the EU or Eurozone Titanic is sinking, from the perspective of ordinary citizens, the ones first into the lifeboats in an orderly way (Brexit) have an advantage. The MMT economists know very well that the Eurozone and EU institutions that control macroeconomic policy are forcing the European economies in a destructive direction primarily because of austerity, the inability for currencies to float relative to each other depending on the current account balance and the inability to run national government deficits of the appropriate magnitude to ensure full employment. Either EU nations one by one readopt their former national currencies, abandon austerity and neoliberalism or the high unemployment, wealth disparity train wreck continues. Either way Brexit was the right move and hopefully Italexit, Frexit and a few others can occur concurrently so that the EU can smoothly transition to a free trade zone of more independent nations with their own currencies much like the former EEC and in addition many nations hopefully realise the last 30+ years of neoliberalism were a mistake and readopt genuine MMT full employment policies.

Colour me a cynic.

I have my doubts that Britain will in fact exit the EU.

The ruling elite and certainly the US doesn’t want Brexit to happen and tactics such as austerity and currency speculation are all components meant to stoke FUD.

Bennadict@Large – Regarding models, can a model ever tell you to do anything it wasn’t programmed to tell you to do? Appropriate to this can a model which was not programmed with MMT considerations ever give economists an MMT answer?

A program will not act contrary to its code (unless the computer system is faulty). That said they can certainly surprise their programmer and frequently do.

An agent-based, stochastic model including accurate accounting practise, would surely largely agree with MMT theory, whether the programmer agreed with MMT or not.

However, I much suspect that the “model” being discussed here is just a simple spreadsheet that calculates the dodgy equilibrium equations that Bill discusses in the article. These are apparently statistical mechanics type “average” behaviour equations, for which apparently there has been no effort made to do the necessary statistical analysis. As such they are guaranteed not to surprise anyone by corresponding to reality.

Simon

I would make clear distinction between being a member of the EU and the Eurozone. I fully accept Wynne Godley’s critique of the Eurozone and I think being a member would have been as disastrous for us as it has been for many of the other members. I would remind you that austerity is not solely a vice of the Eurozone. George Osborne did a pretty good job of inflicting austerity on the UK and I believe that Brexit was one of the fruits of austerity that he didn’t bargain for.

Daniel D,

I tend to agree with you. The referendum vote was never binding, merely a political tool that can very well be ignored like many referendum votes in the past, they will just gauge any possible political fallout. I believe if they were going to do it, they would have initiated article 50 already.

Never had anytime for conspiracy theories but the anti elite politics of

leading brexiters and trump certainly fits a conspiracy model.

The masses unhappy with stagnant incomes and increasing insecurity well promote an anti

elite agenda dominated by the ELITE as Trump puts together a government of the0.01%

There is no doubt that BREXIT will fuel the reactionary right .I voted leave to give

future progressive governments more power to change things for the 99% but fully

expect a more reactionary neo liberal government in the short term.

It was a refeerndum called to secure power for Cameron he won then lost in that context

it was a dumb idea for no policy changes a vote on neo liberal EU or neoliberal populist right.