I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Big business wants government to cut funding them immediately (if only)

Maybe the Australian Government should examine all its contracts with the biggest 121 companies in Australia and cancel them. Perhaps it should, where these companies provide public infrastructure consider setting up not-for-profit public companies to compete against the private 121 (thus lowering prices) and direct all public procurement to these new public institutions. The reason I suggest that is because the Business Council of Australia, which represents the largest companies in Australia (membership equals 121) is demanding the Australian government introduce rather sharp spending cuts or “suffer the consequences”. Okay, a good place to start, might therefore be to cut all public assistance to the companies that are members of the BCA, which would generate huge reductions in government spending. Do you think they would be so aggressive if that was on the table? Not a chance. This is a tawdry lot of corporatists who have had a long history of whingeing about government intervention unless, of course, it is helping grease the profits of their membership. Why the media has given their latest calls for fiscal rectitude the coverage it has reflects on the quality of our media these days.

The membership of this shameless group comprise the pillaging Mining companies, the four major banks and more.

They have been long advocates of privatisation, and opposed a carbon tax and want water rights privatised (that is, in the hands of the large multinationals) so that the market can screw everything in the same way as we are being screwed by energy companies who have been given access to our national resources at bargain basement prices and then send the production (for example, gas) offshore to make huge profits while prices soar in the domestic market as shortages of energy bite.

The Australian government is in the final phases of planning (not that I would call it a plan, given that implies something credible) for its annual May fiscal statement (aka ‘The Budget’).

So the lobby groups are working hard to protect their own corporate welfare cheques from government while demonising the payments to others – particularly those who have little voice like the unemployed, sick and poor.

The top-end-of-town figure that if they make a loud enough noise about cutting the fiscal deficit and point out areas of so-called waste (carefully excluding the handouts they receive), there will be less pressure on government to cut these handouts.

Its the ‘there is a fiscal emergency but it has nothing to do with the spending we benefit from’ type of argument. Very common.

Some background

The big four banks are key members of the BCA and lobby government hard.

Australia’s banking sector is highly concentrated and the big-four major banks hold 78 per cent of the total assets held by all Authorised deposit-taking institutions.

They earn returns on equity that are sometimes twice the comparable bank elsewhere in the world. The Commonwealth Bank, for example, earned a return in 2015 of 18.2 per cent. The other 3 big banks in Australia generate similar returns, a sure sign of market power and a lack of competition.

At present, the big four are mired in scandal as a result of a litany of financial frauds and abuses of market power seeping out into the media. The call for a Royal Commission into their conduct is being vigorously rejected by our conservative government because they know that such an enquiry will expose terrible abuse of the system that the government has allowed to occur because the banksters are their mates (financially and personally).

See this article on – Four myths busted: Why we need a banking royal commission.

They big four promote themselves continually as world leaders in responsible financial management and during the crisis boasted how they did not go down the tube like banks in many other advanced nations.

In terms of the implementation of the new Basel III rules on capital adequacy which has seen the local prudential authority APRA requiring the banks to add more capital as a risk against insolvency (see the press release (August 8, 2013) – Implementation of the Basel III liquidity framework in Australia), the ‘big four’ major banks have waged a campaign for some time against the regulatory move to force them to hold more capital.

They used the usual stunts – ‘too much regulation’, ‘self regulation works fine’, ‘we survived the GFC’, ‘we are the strongest banks in the world’, etc etc.

All just special pleading for a highly protected, oligopolistic sector that can gouge huge returns on equity that are not enjoyed elsewhere in industry or across banking in the world.

They always fail to mention that they were within days of insolvency in late 2008 when their massive exposure to the frozen global wholesale funding markets meant they were unable to repay their maturing loans.

At that point, like all those institutions that survive on ‘corporate welfare’ they went cap in hand to the Federal government and requested that it provide a guarantee on all new foreign currency borrowing.

The government duly agreed and the big four were immediately able to access funds and roll over their debt exposures.

While it is not widely known or discussed (and actively denied by the banks), the entreaty that the banks made to the Federal government was reported in the book “The Great Crash of 2008” (by Garnaut and Llewellyn-Smith) to be along these lines:

In the early days of October 2008, money poured into the big four Australian banks from other financial institutions. But life was becoming increasingly anxious for them as well.

“One by one they advised the Australian government they were having difficulty rolling over their foreign debts. Several sought and received meetings with Prime Minister Rudd. The banks told him that, if the Government did not guarantee their foreign debts, they would not be able to roll over the debt as it became due. Some was due immediately, so they would have to begin withdrawing credit from Australian borrowers. They would be insolvent sooner rather than later …

The government quickly formed the view that the avoidance of a sudden adjustment through the automatic market process was a worthy object of policy. On 12 October it announced that, for a small fee, it would guarantee the banks’ new wholesale liabilities. This would include the huge rollovers of old foreign debt as it matured. The government also announced a guarantee on all deposits up to A$1 million. All four banks expressed their thanks and relief in a joint meeting with the Prime Minister on 23 October …

In Australia, however, the difficulties were on the liability side of bank balance sheets. Banks had become heavily reliant on foreign borrowing and suddenly they were unable to borrow abroad. The non-banks had had no buyers for their securities for almost a year.

There are no degrees of insolvency. A firm is just as insolvent if it is not able to meet its financial obligations as they fall due because it cannot roll over debt, as it is if the value of the assets in its balance sheet is deeply impaired.

The difference is that the problem on the liability side is much more easily (and in most cases cheaply) repaired by a guarantee than the problem on the asset side. The sudden risk of insolvency in Australian banking was simply a more tractable problem than those experienced by other Anglosphere nations.

The banks might counter that they only needed the guarantee because other governments around the world were guaranteeing the debts of their national banks. This does not sit easily against the survival of banks without wholesale funding guarantees in many countries where banks had stayed within the old operational templates- for example Australia’s neighbours Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. In any case, this avoids the point. The Australian banks’ dependence on government-guaranteed debt was exceptional: in July 2009, Australian banks accounted for 10 per cent of the world’s government guaranteed debt. Through foreign borrowing to support domestic lending, the big four Australian banks were active, enthusiastic participants in the global shadow banking system that was now unravelling.

At the time, in inimitable fashion, the Australian Bankers Association put out a press release (October 13, 2009) claiming that “the evidence is that the Australian banks were not insolvent and the wholesale funding guarantee was introduced as a means of ensuring banks could maintain lending growth, not to restore the solvency of banks.”

Which is hilarious – a denial that agrees with the obvious – if they had not gained the guarantee they would have defaulted on loans due. Then their capacity to lend would have disappeared because they would have been bankrupted.

The ABS also said that the major banks could have “secured liquidity from the Reserve Bank” – yes, corporate welfare to survive as their businesses were facing insolvency.

Whichever way you want to look at it, it was the federal government’s currency-issuing capacity that saved the Australian major banks in the dark days of the GFC.

The major banks were not as robust as they make out. They were about to become insolvent and given their dominance in the sector that failure would have had dramatic negative consequences for the Australian economy and would have required a much larger fiscal intervention.

While they had their hands out for government bailouts during the crisis, the CEO of one of the big four banks called on the government to cut unemployment benefits to make workers desperate so they would move to the mining areas (Source).

Of course, the dole is already below the poverty line and the mining boom was over just after he made this call (in 2012).

So the BCA is made up of these sorts – creeps of the tallest order!

Back to the present

In their – 2017-18 Budget Submission, Better Services, Better Value – the BCA claim that:

1. “Continuing opposition to savings measures and the absence of an agreed systematic strategy are just leaving the tab for the deficit and growing debt burden for future generations of Australians to pay.”

2. “Households will face blunt cuts in services, higher taxes and a weaker, less resilient economy.”

3. “Those opposing savings measures have a responsibility to the community to set out alternatives that will deliver a stronger budget and economic growth.”

Why do they say this?

1. “Real spending growth of 3 per cent a year would lock in structural deficits of at least 3 per cent of GDP, doubling to 6 per cent of GDP by mid-century”.

2. “This is unsustainable. Ongoing deficits of even 3 per cent of GDP would create (in today’s terms) some $50 billion additional debt each year.”

3. “Taxes would need to rise by more than $5000 per household per year or by $2000 per person to close the deficit, and by much more to pay off debt.”

4. “Burgeoning debt would leave no buffer to respond to economic shocks – a ‘perfect storm scenario’ – or any capacity for substantial investments in physical and social infrastructure. Other policies, including a more competitive tax system, which are urgently needed to deliver stronger economic growth, would languish.”

The BCA want all sorts of neo-liberal changes implemented – cuts to social security, market-based education, health etc, and, of course, large cuts to the company tax rate.

They claim that the current 30 per cent company tax rate “discourages businesses from investing and innovating, reducing growth and wages”.

What does a casual scan of the data tell us?

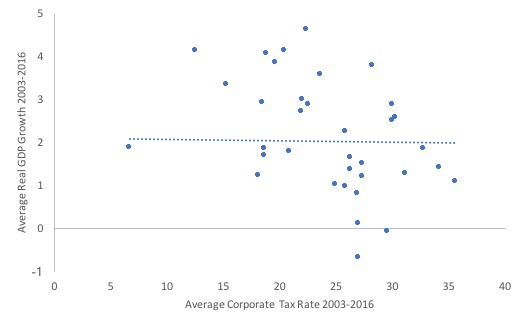

The first graph is constructed using data from the OECD Company Tax database and its Economic Outlook database (National Accounts data).

It shows the average company tax rate between 2003 and 2016 for the OECD block and the average real GDP growth rate for the same period and nations.

The line is a regression trend and it tells you that despite the considerable variation in company tax rates across this large sample of 34 nations, there is no particular relationship with real GDP growth.

BCA lie No 1.

What about growth in investment (that is, productive capacity)? The next graph shows the relationship between company tax rates and average rates of growth in Gross Fixed Capital Formation for the OECD nations between 2000 and 2016.

Conclusion: no relationship.

BCA lie No 2.

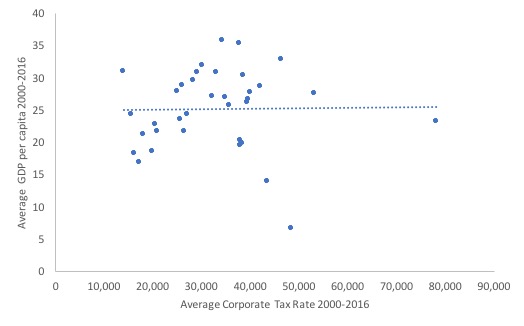

And more to the point on the well-being of people, the next graph shows the relationship between company tax rates and GDP per capita.

That is, the non-relationship. That outlier to the right is the tax haven Luxembourg!

BCA lie No 3.

So not a lot going on to support the cutting company tax rates benefits the wider community.

I could do more sophisticated statistical work here – looking at Australia’s time series behaviour etc – but would reach the same conclusion.

The cuts to the company tax rate since the mid 1980s have coincided with lower real GDP growth rates, lower wages growth, lower productivity, and higher average unemployment and underemployment.

There is not a skerrick of evidence to support the BCA’s lobbying whinge that they need a company tax cut.

But what about their main argument that:

The ultimate goal of government spending must be to improve community living standards through the provision of crucial services such as education and health care, public infrastructure, national defence and a social safety net to protect the most vulnerable …

[But] … our continuing poor budget position undermines capacity to improve living standards …

A growing fiscal gap will lead to a debt blow out and much higher taxes or blunt program cuts … Without action, the fiscal gap will grow ever wider – until it provokes a painful economic correction involving both cuts to services and higher taxes …

Structural deficits of at least 3 per cent are being locked in, creating (in today’s terms) some $50 billion additional debt each year ….

Deficits are not an escape route. They are just a credit card – in Australia’s case, one issued by foreign lenders. The debt has to be repaid in the future by taxpayers or by cutting services …

High debt exposure is impairing our capacity to respond to economic shocks and threatening Australia’s AAA credit rating …

The window for action is rapidly closing …

Budget repair will require both immediate measures to prevent deterioration or slippage in the budget position and deeper structural reforms of major areas of expenditure over the medium term to shore up budget sustainability well ahead of 2025 …

The economy’s capacity to fund spending is diminishing just as the risk of global economic upheaval is increasing …

Progressively return the budget to surplus to build resilience and flexibility for dealing with economic shocks and volatility, and for underpinning business confidence and investment.

Oh, my god! Its a catastrophe! The window is “rapidly closing” – let some air in. Hack into government spending, quick, before it is too late.

In that last set of quotes almost every one of the neo-liberal (lying) claims are rehearsed.

Oh, I forget to add:

Budget improvement is crucial for safeguarding the prosperity of current and future generations.

Ah, I feel better now. Our grandchildren are also in peril. We will all go down together in the deficit spiral!

F*ck, where does one start with all of that.

The ABC news report of the BCA’s release – Budget repair urgently needed or ordinary Australians will suffer, Business Council says – certainly didn’t make any reasonable start on informing its readers etc of the nonsensical nature of the BCA’s claims.

It chose to repeat claims like:

The BCA equates the alarming scenario of possible social security cuts to eliminating the entire education and defence budgets,

Okay, kids and grandkids, not only are we going to lumber you with debt that will have to pay off once we have lived it up and sailed off into the heavenly sunset, but we are going to deprive you of education and leave you vulnerable to foreign invasion.

We are a nice lot, eh!

But, don’t despair, the ABC reported that:

Without dramatic cuts, the BCA said social services would have to be slashed, which could see the equivalent of a third of today’s social security budget reduced.

So we are going to attack some of us too – the weak ones, who cannot fight back.

The ABC is our national broadcaster and claims it must present all views. That news report had no alternative view and our public broadcaster is fast becoming just another megaphone for the self-serving neo-liberal corporatist lobby.

So in this fake news era, here are the facts (in summary form). If you want chapter and verse go to my Debriefing 101 Category and start at the beginning.

Pushing back towards a fiscal surplus will drive the private domestic sector into even higher debt

The fiscal deficit in Australia is currently running around 2 per cent GDP.

The average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2015-16 has been -3.9 per cent of GDP. So we might consider that sort of performance to continue. There is certainly no expectation that the current account will suddenly record the outcomes assumed.

What does that mean in terms of the sectoral balances, which show a relationship from the national accounts between spending and income for the three-major sectors in the economy: (a) the external sector; (b) the private domestic sector; and (c) the government sector. (a) and (b) sum to be the non-government sector.

The sectoral balances must hold as an accounting statement and we then need to interpret their evolution by understanding what drives the individual balances.

Please see – Answer to Question 3 – for the complete explanation of the sectoral balances approach and derivation.

The final sectoral balances expression that results from that derivation is that:

(S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

where S is private domestic saving from disposable income, I is private domestic capital formation investment, G is total government spending, T is government taxation receipts, and the CAD is the current account deficit (the trade deficit plus net income transfers abroad).

The sectoral balances equation is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

This allows the private domestic sector to save overall (which is different from household saving out of disposable income denoted S above). That means, the private domestic sector is spending less than its total income and building wealth in the form of financial assets.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T less than 0) and current account deficits (CAD less than 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

The previous expression can also be written as:

[(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

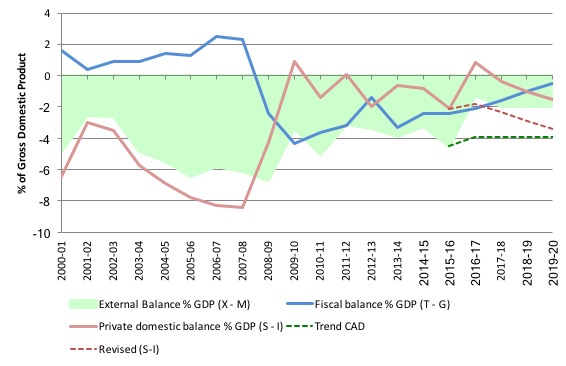

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2019-20, with the forward years using the latest Treasury projections. The blue line is the fiscal balance.

The graph shows two projections of the external account (from 2016-17 on):

1. The latest Treasury projections (captured by the green area after the dotted series start) – which demarcates the point in time between actual and projected).

2. The average current account position since the 1973-74 – that is, a deficit of 3.9 per cent of GDP (green dotted line).

Correspondingly, I computed two balances for the private domestic sector conditional on the Treasury fiscal estimates and the two different external assumptions:

1. The balance implied in the actual Treasury projections – the red line after black demarcation line.

2. The balance that would arise if the external deficit was around its long-term average (a more realistic assumption) – dotted red line after black demarcation line.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

So the BCA strategy to push the fiscal balance towards surplus would push the private domestic sector into higher indebtedness, on any of the external deficit assumptions.

That descent into more debt would be worse if we follow the more realistic external balance path (the dotted lines).

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09, which saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit – not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to move towards rebalancing its precarious debt position.

The fiscal strategy now being pursued by the Government and cheered on by the BCA now implies, as the graph shows, that the private domestic sector will once again be accumulating debt as it progressively spends more than its income.

With investment flat, the debt would fall onto households, who are already carrying record levels of indebtedness.

We are on the path back to the excessive private domestic debt levels that prevailed before the GFC.

But it is also clear that private spending growth would have to break all bounds to be consistent with these projections and still maintain economic growth.

That will not happen.

So the pursuit of fiscal surpluses will just add fiscal drag to an already subdued non-government spending outlook and growth will suffer and labour underutilisation will rise.

Not a sustainable strategy at all.

The BCA seems transfixed on fears that the government debt in Australia is too high. But nary a word gets mentioned about the dangerous private debt levels, which will restrain private spending overall.

It is unlikely we will see a return to the pre-crisis period when private debt grew much faster than disposable income and the resulting spending maintained stronger economic growth.

What is a poor fiscal position?

Is a fiscal deficit of 2 per cent a sign of a “continuing poor budget position”, as the BCA claims?

We cannot say anything about the appropriateness of the fiscal settings by merely quoting a figure like 2 per cent.

A deficit of 10 per cent of GDP might be appropriate, just as a surplus of 1 per cent might be.

There is no economic logic in assuming a higher deficit is a deterioration and vice versa.

It all depends on the context.

We could have a deficit of 2 per cent of GDP associated with elevated levels of unemployment, which I would call a ‘bad’ deficit and the same size deficit associated with full employment (a ‘good’ deficit).

Trying to cut a deficit by increasing unemployment is a stupid thing to do. Typically, the outcome will be a rising deficit (as tax revenue falls with lower activity) and a recession.

Expanding a deficit through discretionary net spending initiatives is a wise thing to – the deficit supports growth, non-government saving and achieves the aim of fiscal policy – full employment and rising prosperity.

Please read my blog – The full employment fiscal deficit condition – for more discussion on this point.

Foreigners do not issue Australian dollars

The BCA claims that “deficits … are just a credit card – in Australia’s case, one issued by foreign lenders. The debt has to be repaid in the future by taxpayers or by cutting services”.

First, the credit card analogy is inapplicable to a currency-issuing government. It is an attempt to use the so-called ‘household budget’ analogy to make sense of government financial relations.

The household is a user of the currency that the government issues.

The government doesn’t need ‘credit’ in order to spend above its taxation revenue.

The government doesn’t ‘need’ pre-existing funds to spend; neither does it ‘need’ to offset the deficit by issuing debt to the non-government sector, given that it can create the currency ‘out of thin air’.

The issuance of debt is a voluntary act – a provision of corporate welfare – and the government would be wise to stop this archaic practice.

Further, the Australian government issues the Australian dollar that it spends by crediting a reserve accounts at the central bank.

Foreigners do not issue the Australian dollar. The BCA claim is a bare-faced lie or the utterance of an ignoramus or, probably both.

Do we pay back past deficits?

Answer: No. They are flows and are gone the moment they are realised.

If the government engages in voluntary matching of its deficit with debt-issuance then the stock of debt can accumulate as non-government wealth.

When the Australian government started running down the stock of outstanding public debt (1996-2000), the private investment banks and future traders were so incensed that they pressured the government into contining to issue debt even though the fiscal balance was in surplus.

Why? They love welfare!

Governments roll over debt as it older debt matures. But that doesn’t have any implications for tax rates or service provision.

Every generation chooses it tax rates through the ballot box.

Further, the capacity of the government to spend today is not at all constrained by what it did yesterday, except in the sense that the limits on government spending are the real resources available for sale in the currency of issue.

So if the government is running deficits and sustaining full employment then it has no further need to expand net spending.

But to say that a deficit today limits the financial capacity of the government to spend and run a deficit tomorrow or next year is a is a bare-faced lie (and/or the ignoramus bit!).

The AAA credit rating myth

Holding out the credit rating agencies as anything important for a currency-issuing government to consider is nonsensical. They are irrelevant.

Please read my blog – Don’t fall for the AAA rating myth – for more discussion on this point.

Those grandkids

Following the BCAs plan would undermine the future of our grandchildren by denying them employment and training opportunities and cutting their wages (if they could get a job).

Please read my blogs:

1. Austerity is killing off the hopes of our youth.

2. The CEDA Report – one of the worst ever.

3. Australia – the Fourth Intergenerational Myth Report.

Conclusion

Anyway, the Government might want to start hacking into corporate welfare. They could start with the banks. Next time they get ahead of themselves, the Government should let them go broke and then nationalise them. Most of us would be better off by far.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I apologise for the digression, but I’d like to buy the intermediate book entitled “Macroeconomics in the 21st Century: A Modern Monetary Theory Text“ which I believe was originally expected to come out at the end of 2016. I was wondering what has happened to it. Thanks

I made a sectoral balances graph using historical data from Budget Paper 1 (table 6 beginning 1996-97), and current account balance data from the RBA statistics page. But to make it look like the one above, I have to use quarterly current account data beginning from Sep-1995. Is that correct?

“Banking should be a public utility.” Michael Hudson, “Killing the Host.”

The BCA is a treasonous pox on the body politic.

I don’t know whether to despair or find comfort in the old adage “The worse things get the better” (Churchill, I believe).

BTW Bill, the “Average GDP” and “Average Corporate Tax Rate” tags on graph 3 are on the wrong axes.

Dear Allan (at 2017/03/22 at 4:43 pm)

The fiscal data is financial year. So you have to convert the quarterly Current Account data into fiscal year – July-June.

best wishes

bill

Couldn’t agree more, try as I might.

Yes nationalise the big 4 banks as well as the resources sector and utilities/infrastructure. The private sector can do the construction and much of the operational role in a competitive market with the government sector retaining ownership. The mass media and political class must be purged first.

Hear hear, Bill. I couldn’t agree more. Tell the 121 that their era of largesse is over. The “age of entitlement” in Hokey’s [sic] immortal words is over – for them.

It seems that the 121 have failed to grasp that cutting government spending into the real economy, which is what they appear to be advocating, will have a negative impact on their profits because demand will be commensurately reduced (with or without the benefit of corporate welfare).

Get rid of corporate welfare. Get rid of corporate taxes too.

“The fiscal data is financial year. So you have to convert the quarterly Current Account data into fiscal year – July-June.”

That’s what I did. But I had to start from the Sep-1995 quarter.

I may have it wrong, but I thought it should be from Sep-1996 for the fiscal year 1996-97.

How things have changed – back in the days when the CBA was publicly owned, a friend of mine went along to see his local CBA manger – he wanted to buy an investment property (this was in the 70s). He was told “we are here for the needy, not the greedy” and so was sent on his way and later got the money from a credit union.

Dr. Mitchell,

I notice that your sectoral balance includes income transfers. If I correctly recall, up until a year ago you had not included income transfers, only exports and imports. Were the old models inaccurate? Thanks –