Today (April 18, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Labour Force,…

US labour market – hard to read at present but probably improving

On April 7, 2017, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released their latest labour market data – Employment Situation Summary – March 2017 – which showed that total non-farm employment from the payroll survey rose by only 98,000, a considerable shortfall when compared to the previous two months. The unemployment rate fell to 4.5 per cent (down 0.2 points). The question is whether this month’s results signal a slowdown after the positive ‘Trump’ spike or is just a monthly variation that will iron itself out over the longer period. Whatever the direction, there is still a large jobs deficit remaining and the jobs created since the recovery are still biased towards low pay sectors.

Overview

For those who are confused about the difference between the payroll (establishment) data and the household survey data you should read this blog – US labour market is in a deplorable state – where I explain the differences in detail.

See also the – Employment Situation FAQ – provided by the BLS, itself.

The BLS say that:

The establishment survey employment series has a smaller margin of error on the measurement of month-to-month change than the household survey because of its much larger sample size. … However, the household survey has a more expansive scope than the establishment survey because it includes self-employed workers whose businesses are unincorporated, unpaid family workers, agricultural workers, and private household workers …

Focusing on the Household Labour Force Survey data, the seasonally adjusted labour force rose by by 145 thousand in March 2017 and the participation rate was unchanged at 63 per cent.

The participation rate has risen from 62.6 per cent in November 2016 to 63 per cent in March 2017, which is usually a sign that employment opportunities are becoming easier to access.

Total employment rose by 472 thousand in net terms, and as a consequence, official unemployment fell by 326 thousand.

The unemployment rate eased from 4.7 per cent to 4.5 per cent.

These swings are most unusual given the weak payroll data (see below) and have to be treated with some suspicion.

While it is too early to say whether the stronger growth so far this year is reversing the slowdown experienced in the second-half of 2016, the signs are there.

Caution is always required in interpreting monthly data.

Remember, that the US economy has been undermining standard wage employment since 2005 (see – All net jobs in US since 2005 have been non-standard) and has demonstrated a bias towards low-wage job creation (see below for updated analysis).

Further, the February participation rate was still only 63 per cent and still far below the peak in December 2006 (66.4).

Adjusting for the ageing effect (see US labour market – some improvement but still soft for an explanation of this effect), the rise in those who have given up looking for work (discouraged) since December 2006 is around 3.6 million.

If we added them back into the labour force and considered them to be unemployed (which is not an unreasonable assumption given that the difference between being classified as officially unemployed against not in the labour force is solely due to whether the person had actively searched for work in the previous month) – we would find that the current US unemployment rate would be around 6.7 per cent rather than the official estimate of 4.7 per cent.

That provides a quite different perspective in the way we assess the US recovery.

The US labour market is still a long way from where it was at the end of 2007.

Payroll employment trends

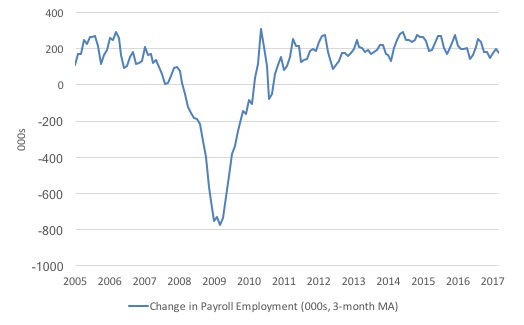

The first graph shows the monthly change in payroll employment (in thousands, expressed as a 3-month moving average to take out the monthly noise).

The monthly changes were stronger in 2015, and then dipped in the first-half of 2016. By the end of 2016, job creation was stronger but then it tailed off again, somewhat.

In the first two months of 2017 (January and February), there was a strengthening of the net payroll employment change. But with the March result so poor, the average change so far in 2017 (178 thousand) is the lowest since 2011.

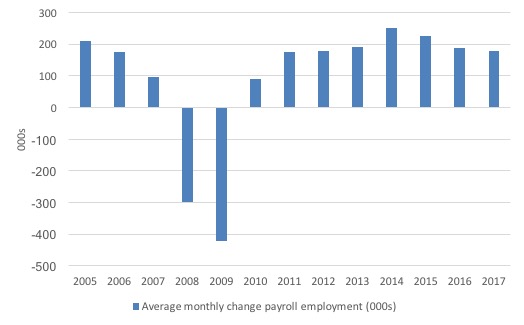

The next graph shows the same data in a different way – in this case the graph shows the average net monthly change in payroll employment (actual) for the calendar years from 2005 to 2017. Clearly, the average for 2017 is for January to March only.

The data suggests that the downward trend that began in 2014 continues.

The average net change in 2014 was 250 thousand, in 2015 was 226 thousand, in 2016, 187 thousand. As noted above, the average net change so far in 2017 is just 178 thousand.

Labour Force Survey – employment growth picking up

In March 2017, employment increased by 0.31 per cent compared to the 0.09 per cent rise in the labour force. That is why the unemployment level fell by 326 thousand.

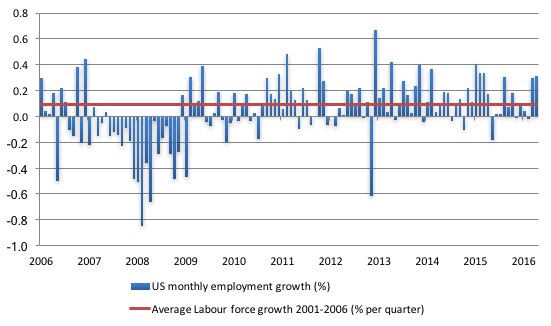

The following graph shows the monthly employment growth since the low-point unemployment rate month (December 2006). The red line is the average labour force growth over the period December 2001 to December 2006 (0.0910 per cent per month).

What is apparent is that a strong positive and reinforcing trend in employment growth has not yet been established in the US labour market since the recovery began back in 2009. There are still many months where employment growth, while positive, remains relatively weak when compared to the average labour force growth prior to the crisis.

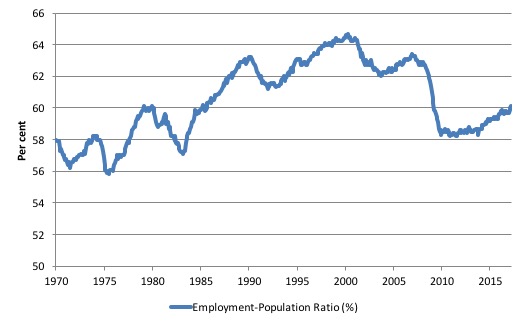

A good measure of the strength of the labour market is the Employment-Population ratio given that the movements are relatively unambiguous because the denominator population is not particularly sensitive to the cycle (unlike the labour force).

The following graph shows the US Employment-Population from January 1970 to March 2017. While the ratio fluctuates a little, the March 2017 outcome (60.1 per cent) was up by 0.4 points on December.

But it remains well down on pre-GFC levels (peak 63.4 per cent in December 2006), which is a further indication of how weak the recovery has been so far.

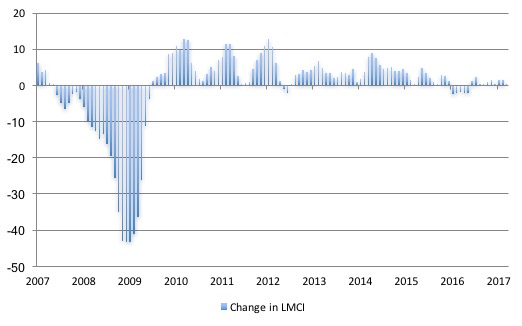

Federal Reserve Bank Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI)

The Federal Reserve Bank of America has been publishing a new indicator – Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI) – which is derived from a statistical analysis of 19 individual labour market measures since October 2014.

It is now being watched by those who want to be the first to predict a rise in US official interest rates. Suffice to say that the short-run (monthly) changes in the LMCI are “assumed to summarize overall labor market conditions”.

A rising value (positive change) is a sign of an improving labour market, whereas a declining value (negative change) indicates the opposite.

You can get the full dataset HERE.

I discussed the derivation and interpretation of the LMCI in this blog – US labour market weakening.

In March 2017, the LMCI rose by 0.4 index points down from 1.5 and continues the relative weak trend downwards since 2015.

The following graph shows the FRB LMCI for the period January 2007 to January 2017. At the time of writing, the February data had not yet been released.

We note that while unemployment is now lower than last year and the rate of hiring has stabilised after declining earlier in the year. The way these factors combine in the index leads to an overall assessment that the labour market has been in decline.

The fall away over the last nine months has been quite significant notwithstanding the July 2016 upturn. The index remains positive though.

The US jobs deficit

As noted in the Overview, the current participation rate (63 per cent) is a long way below the most recent peak in December 2006 of 66.4 per cent.

When times are bad, many workers opt to stop searching for work while there are not enough jobs to go around. As a result, national statistics offices classify these workers as not being in the labour force (they fail the activity test), which has the effect of attenuating the rise in official estimates of unemployment and unemployment rates.

These discouraged workers are considered to be in hidden unemployment and like the officially unemployed workers are available to work immediately and would take a job if one was offered.

But the participation rates are also influenced by compositional shifts (changing shares) of the different demographic age groups in the working age population. In most nations, the population is shifting towards older workers who have lower participation rates.

Thus some of the decline in the total participation rate could simply being an averaging issue – more workers are the average who have a lower participation rate.

I analysed this declining trend in this blog – Decomposing the decline in the US participation rate for ageing.

I updated that analysis to December 2015 and computed that the decline in the participation rate due to the shift in the age composition of the working age population towards older workers with lower participation rates accounted for about 58 per cent of the actual decline.

Thus, even if we take out the estimated demographic effect (the trend), we are still left with a massive cyclical response.

What does that mean for the underlying unemployment?

The labour force changes as the underlying working age population grows and with changes in the participation rate.

If we adjust for the ageing component of the declining participation rate and calculate what the labour force would have been given the underlying growth in the working age population if participation rates had not declined since December 2006 then we can estimate the change in hidden unemployment since that time due to the sluggish state of the US labour market.

Adjusting for the demographic effect would give an estimate of the participation rate in March 2017 of 64.5 if there had been no cyclical effects (1.5 percentage points up from the current 63 per cent).

So the 1.5 percentage point decline in the participation rate due to the downturn (net of ageing effect) amounts to 3,567 thousand workers who have left the labour force as a result of the cyclical sensitivity of the labour force.

It is hard to claim that these withdrawals reflect structural changes (for example, a change in preference with respect to retirement age, a sudden increase in the desire to engage in full-time education).

In January 2007 (at the peak participation rate which had carried over from December 2006), the US unemployment rate was 4.6 per cent (which was slightly higher than the 4.4 per cent low point recorded a month earlier in December 2006. It didn’t start to increase quickly until early 2008 and then the jump was sudden.

We can have a separate debate about whether 4.4 per cent constitutes full employment in the US. My bet is that if the government offered an unconditional Job Guarantee at an acceptable minimum wage there would be a sudden reduction in the national unemployment rate which would take it to well below 4.4 per cent without any significant inflationary impacts (via aggregate demand effects).

So I doubt 4.4 per cent is the true irreducible minimum unemployment rate that can be sustained in the US.

But we will use it as a benchmark so as not to get sidetracked into definitions of full employment. In that sense, my estimates should be considered the best-case scenario given that I actually think the cyclical losses are much worse than I provide here.

For those mystified by this statement – it just means that I think the economy was not at full employment in December 2006 and thus was already enduring some cyclical unemployment at that time.

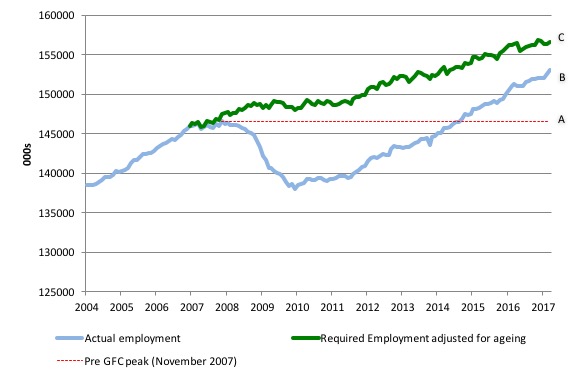

Using the estimated potential labour force (controlling for declining participation), we can compute a ‘necessary’ employment series which is defined as the level of employment that would ensure on 4.4 per cent of the simulated labour force remained unemployed.

This time series tells us by how much employment has to grow each month (in thousands) to match the underlying growth in the working age population with participation rates constant at their January 2007 peak – that is, to maintain the 4.4 per cent unemployment rate benchmark.

I computed the ‘necessary’ employment series based on the age-adjusted potential labour force (dark green line in the following graph).

The light blue line is the actual employment as measured by the BLS and the dotted red line is the level of employment that prevailed in November 2007 (the peak before the crisis).

This allows us to calculate how far below the 4.4 per cent unemployment rate (constant participation rate) the US employment level currently is.

There are two effects:

- The actual loss of jobs between the employment peak in November 2007 and the trough (January 2010) was 8,582 thousand jobs. However, total employment is now above the January 2008 peak by 6,405 thousand jobs. This gain in jobs is measured by the AB gap in the graph which shows the gap in employment relative to the November 2007 peak (the dotted red line is an extrapolation of the peak employment level). You can see that it wasn’t until July 2014 that the US labour market reached the November 2007 peak employment level again.

- The shortfall of jobs (the overall jobs gap) is the actual employment relative to the jobs that would have been generated had the demand-side of the labour market kept pace with the underlying population growth (Required Employment Adjusted for Ageing) – that is, with the participation rate at its December 2006 peak and the unemployment rate constant at 4.4 per cent. This shortfall (BC) loss amounts to 3,556 thousand jobs. This is the segment BC measured as at March 2017.

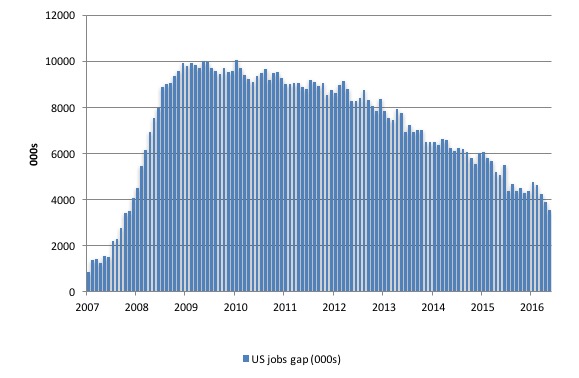

The next graph shows the difference between the blue and green lines in the above graph. The US Jobs Gap is thus the departure of current employment from the level of employment that would have generated a 4.4 per cent unemployment rate, given current population trends.

While the jobs gap is declining, it is still substantial.

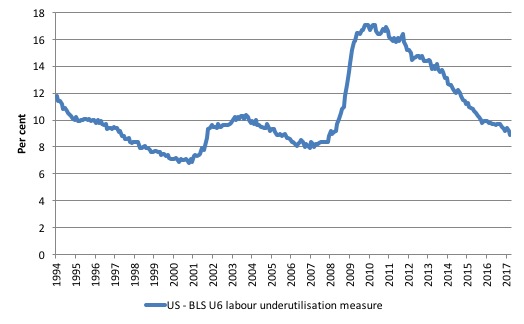

To put that into further perspective, the following graph shows the BLS measure U6, which is defined as:

Total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of all civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers.

It is thus the broadest measure of labour underutilisation that the BLS publish.

In December 2006, before the affects of the slowdown started to impact upon the labour market, the measure was estimated to be 7.9 per cent. It now stands at 8.9 per cent (March 2017) which means it has fallen by 0.5 points since the end of 2016, another reason why I am thinking this month represents improvement.

The U-6 measure fell by 0.3 points in March alone.

While showing improvement, the U-6 measure remains well above previous troughs, which suggests (along with the other signals presented above) that the labour market is still some way from being considered ‘recovered’.

It means that while unemployment has declined modestly over the last year, underemployment and hidden unemployment have risen.

The low-wage employment bias

To see the full methodology I employed in making these calculations please read the blogs – US jobs recovery biased towards low-pay jobs and Bias toward low-wage job creation in the US continues.

I last computed the low-wage bias in June 2016, so it is worth seeing whether the trends identified then were persisting.

The question: Is there a bias towards low-pays jobs in the recovery in the US?

Answer: bias continues.

Effectively, since the recovery began in January 2009, there have been 16,080 thousand net jobs added to the US labour market (in the non-farm sector).

Of those net employment additions, 27 per cent have been what might be considered low-pay, where that is defined as less than 75 per cent of average weekly earnings.

Previously, I have calculated what happened in the downturn with respect to the jobs lost in net terms and their pay characteristics (at a sectoral level).

Peak US non-farm employment occurred in January 2008 (138,432 thousand) and the trough occurred in December 2009 (129,774 thousand).

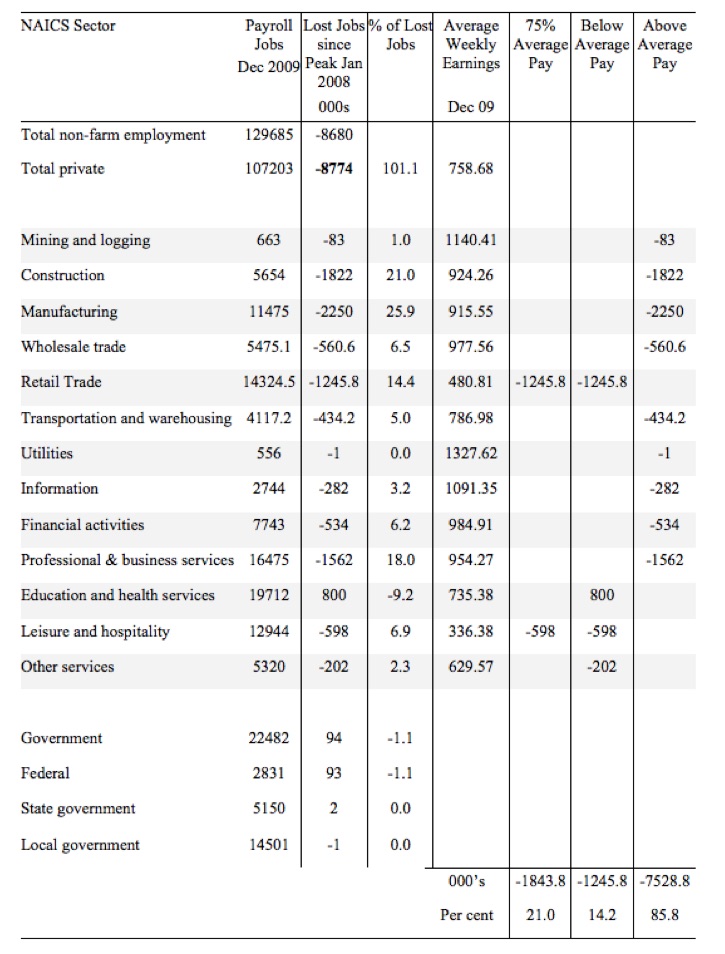

Using the top-level North American Industry Classification System (2012 NAICS), we can calculate the job losses that occurred from peak (January 2008) to the trough (December 2009).

The following table summarises what happened in the Peak-trough period.

The first column shows the NAICS sector with the first two rows summarising relevant totals. Total non-farm employment is the sum of total private employment plus Government employment.

The second column shows the total employment in each sector as at December 2009, which was the trough of the downturn following the peak in January 2008.

The third column shows the lost jobs (in thousands) between the Peak and the Trough (these are net losses). So overall 8.7 million jobs were lost – with 8.8 million lost in the private sector and they were only partially offset by the 94,000 net jobs added in the government sector.

The next column shows the percentage of those lost jobs per sector, which allows you to see where the downturn impacted mostly. The next column shows average weekly earnings as at December 2009 in US dollars.

The final three columns then distribute the jobs lost according to whether the sector pays 75 per cent or less than average pay, below average pay (the first being a subset of the second), or above average pay as at December 2009.

The totals are below the last three columns and the percent indicates the percent of total jobs lost in each of the pay categories.

So in the downturn, from January 2008 to December 2009, 21 per cent of the jobs lost (net) were in sectors that paid on average below 75 per cent of the overall private sector average pay.

The last two columns divide the total job losses in net terms between above and below average pay and you can see that 85.8 per cent of the total jobs lost in the downturn were in sectors were paying above average pay.

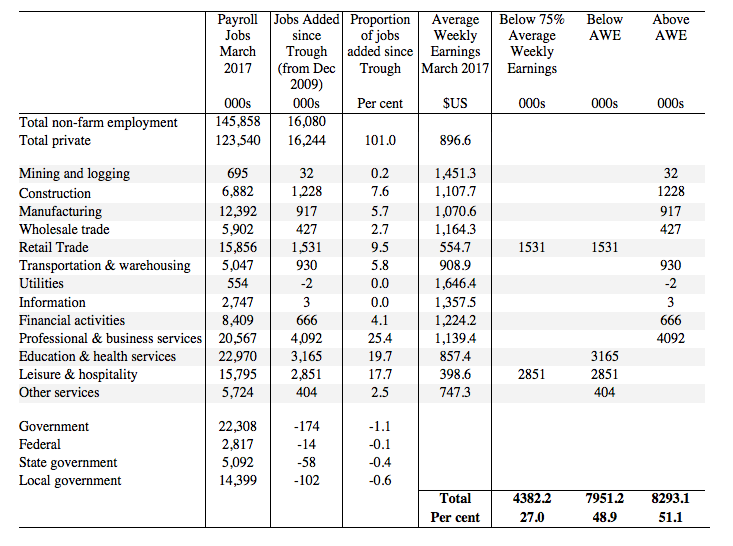

The next table summarises what happened in the period from the trough to the most recent monthly data observation (March 2017).

The columns now have a slightly different interpretation, given that we are discussing a growth period rather than a period of contraction.

The second column shows the latest BLS payroll employment data as at March 2017. The next column shows the number of net jobs (in thousands) that have been added by each sector since the trough in December 2009.

The next column shows the percentage of those total jobs added by sector. You can see that with the Government sector in contraction the total jobs added in the Private sector are 101 per cent of the total net jobs added.

The fourth column shows the Average Weekly Earnings for each sector as at March 2017.

The final three columns split these job additions into their pay characteristics using the sectoral average weekly earnings and the same criteria as in the previous example.

The summary statistics for each ‘pay category’ (75% of Average Pay, Below Average Pay, Above Average Pay) are at the bottom of each column.

We find that:

1. Government employment has contracted in the expansion, particularly at the Local Government level as fiscal austerity has been imposed.

2. 27 per cent of the total jobs added could be considered low-pay, that is, in sectors that pay on average weekly wage 75 per cent below the total private sector average weekly earnings.

3. 48.9 per cent of the jobs created (net) since the recovery began pay below average weekly earnings. That proportion was 50.4 per cent in May 2016.

The data shows that the low-paid jobs that were lost in the downturn have been more than added back (in net terms) in the upturn so far.

The above average pay jobs that were lost in the downturn (7,528.8 thousand) have now been more than added back in net terms (8,293.1 thousand).

This analysis shows a bias in the recovery towards low-paid jobs in the US which persisted until the middle of 2016 is persisting considering that in January 2008, 41.4 per cent of total private sector jobs were below average pay.

By March 2017, the proportion had risen to 44.2 per cent.

But, it is also true that more above-average jobs have now been added than low wage jobs in the recovery, which will reduce that bias over time, if the trend continues.

Clearly, this analysis is at the aggregated NAICS level and a richer story could be told if we used the two-digit and three-digit typed drill downs into the industry classification.

Conclusion

The evidence is fairly consistent across a range of measures – the mass unemployment in the US was the result of a systemic failure in that economy to produce enough jobs, which emerged as aggregate spending collapsed in early 2008.

Since then, as the economy has slowly starting growing again, the demand-side of the labour market has improved steadily and the unemployment rate has fallen.

The pace of improvement slowed in 2016 and after two positive months (January and February), the March 2017 data is sending mixed signals.

Clearly, payroll employment is down sharply while the Labour Force Survey data is holding up.

Which movement is a more accurate signal of what is to come remains to be seen. Some say the payroll data is a more accurate forward indicator, which means the US labour market is deteriorating.

We will have to wait and see.

And on a final note – tonight I am in Sydney to attend the concert by Patti Smith and her band. I think it will rock a lot, which I recommmend as we get older!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Japan now is interesting case with unemployment that has fallen to 2.8% and over twice as many job openings as there are job seekers, inflation still is non-existant.

Just to say that about line 13 of Overview you say that ‘participant rate has risen from 62.6 percent to 63 percent.’ Well I’m afraid that my wife tells me (she’s a mathematician) that from 62.5 per cent to 63.4 will take the value of 63. You’re mixing up two methods of recording figures, ie whole numbers, or, to one decimal place. Did you make a mistake in recording one of the numbers?

Well I see from today’s editorial in the ‘Morning Star’ that Labour are going to start an investment bank where we’ll all be able to contribute towards investment if they get in at the next General Election. Not a mention of using the Central Bank to invest in major projects. Sounds like they’re still living in a Household Budget economy. Can you please sort them out? Thanks!