It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

Eurozone remains in much worse shape than some official statistics might suggest

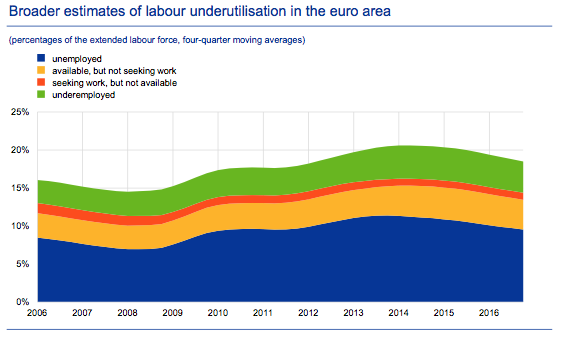

On May 11, 2017, the European Central Bank (ECB) released its third Economic Bulletin for the year, the release date comes two weeks after each of their monetary policy meetings. In Issue 3, there is some interesting analysis on both the state of youth unemployment and the degree of labour market slack in the Eurozone. It doesn’t paint a very rosy picture despite the constant claims that the Eurozone is recovering well. The reality is that while the official unemployment rate is bad enough (still above the pre-crisis level and stuck at around 9.5 per cent), the broader measures of labour slack indicate that around 18.5 per cent (at least) of the productive labour resources in the Eurozone are lying idle in one form or another. The broad slack has also risen during the crisis in most nations – particularly underemployment. In other words, the Eurozone remains in much worse shape than some official statistics might suggest. And we are nearly a decade into the crisis (and so-called ‘recovery’).

Youth unemployment

I will deal with this topic separately in another blog because the European Court of Auditors recently published a fairly comprehensive evaluation of the youth unemployment in the context of the Youth Guarantee scheme introduced to combat the high joblessness for 15-24 year olds.

The Audit is rather negative and I am still digesting its contents.

But the ECB Economic Bulletin notes that:

1. “the youth unemployment rate has declined faster than the total unemployment rate and remained around 21% in 2016, about

6 percentage points higher than in 2007.”

2. Persistently high youth unemployment of the sort that the Eurozone has experienced has “scarring effects” on young workers which results in “increased risks of future unemployment, human capital losses and lower earnings. Youth unemployment rates are normally higher than total unemployment rates”.

3. “Youth unemployment in the euro area remains above its pre-crisis level, but the ratio of youth unemployment to total unemployment has hardly changed.”

This means that “youth unemployment has moved in line with total unemployment” and thus supply-side policies that try to make the problem as being cohort-specific are flawed.

The problem is not that the youth don’t look for work hard enough, or have deficient characteristics, or ‘cost’ employers too much – the standard neo-liberal dodges – but, rather, that there is a systemic shortage of jobs that impacts on all workers – young and old.

But the ECB’s solutions are all supply-side:

(1) improving the quality and the labour market relevance of education, including via well-developed apprenticeship systems; (2) ensuring a well-functioning and responsible wage setting system, including when setting minimum wages;

(3) enhancing the role of public employment services and the provision of active labour market policies with a view to supporting the unemployed during labour market transitions and increasing their employability; (4) increasing working time flexibility in order to facilitate a combination of work and education and to ease the transition from education to employment in the labour market.

And among those “policy measures” there is not a job in sight!

Assessing labour market slack

The other special focus topic in Issue 3 was on the correspondence between the official labour market data (unemployment rate etc) and the underlying degree of labour market slack in the Eurozone.

The short conclusion was that the official data grossly understates how bad things remain in the monetary union for workers and their families.

The Financial Times also covered this analysis (May 10, 2017) – Plight of eurozone jobless found to be worse than data show.

On May 23, 2017, Eurostat news release – 9.5 million part-time workers in the EU would prefer to work more – bears on this discussion.

We learned that while the part-time ratio (to total employment) in the Eurozone was 20 per cent – of those:

… 45.3 million people working part-time, 9.5 million were underemployed, meaning they wished to work more hours and were available to do so. This corresponds to a fifth (20.9%) of all part-time workers and 4.2% of total employment in the EU in 2016.

That is a very high underemployment rate.

It will come as no surprise that the “Largest share of underemployed part-time workers … [was] … in Greece”. So not only is total official unemployment in Greece diabolically high still but 74.1 per cent of its part-time workers are underemployed.

The proportion in Cyprus is 63.7 per cent, Spain 50.7 per cent, and Portugal 45.1 per cent.

The underemployment rate (the percentage of underemployed in the labour force) has also risen since 2008. In 2016, for the 15 to 74 years cohort, it was 3.9 per cent up from 3.2 per cent in 2008.

For the prime-age group (25 to 54 years), it was 3.8 per cent for the 28 countries of the European Union compared to 3.1 per cent in 2008.

As a proportion of total employment, underemployment in the EU for the 15-74 years group has risen from 3.5 per cent to 4.2 per cent. The prime-age proportions was 4.1 per cent in 2016 up from 3.3 per cent in 2008.

The ECB Bulletin special box acknowledges these trends and presents a new measure of labour market slack.

It notes that:

Despite broad improvements in euro area labour markets since the start of the recovery and a marked decline in unemployment rates across many euro area economies, wage growth remains subdued, suggesting that there is still a considerable degree of labour market slack.

The ECB note that the “The unemployment rate is based on a rather narrow definition of labour underutilisation”.

They note that the official unemployment rate is calculated using methods endorsed by international conventions.

As background, the labour force framework is the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data and is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop guidelines or norms for implementing the framework and generating national labour force data.

The rules contained within the framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework – employment, unemployment, not in the labour force;

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework; and

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at some point in time – usually what is referred to as the “reference week” (the week of the survey).

The system of priority rules ensure that labour force activities take precedence over non-labour force activities and working or having a job (employment) takes precedence over looking for work (unemployment). As with most statistical measurements of activity, employment in informal sectors lies outside the scope of measurement.

Paid activities take precedence over unpaid activities. For example, ‘persons who were keeping house’ as used in Australia, on an unpaid basis are classified as not in the labour force while those who receive pay for this activity are in the labour force as employed.

Similarly persons who undertake unpaid voluntary work are not in the labour force, even though their activities may be similar to those undertaken by the employed.

In terms of those out of the labour force, but marginally attached to it, the ILO considers that persons marginally attached to the labour force are those not economically active under standard definitions of employment and unemployment, but who, following a change in one of the standard definitions of employment or unemployment, would be reclassified as economically active.

For example, changes in criteria used to define availability for work (whether defined as this week, in the next 4 weeks etc.) will change the numbers of people classified to each group.

Underutilisation is a general term describing wastage of willing labour resources. It arises from a number of different reasons that can be subdivided into two broad functional categories.

First, there is a category involving unemployment or its near equivalent.

In this group, we include the official unemployed under ILO criteria and those classified as being not in the labour force on search criteria (discouraged workers), availability criteria (other marginal workers), and more broad still, those who take disability and other pensions as an alternative to unemployment (forced pension recipients).

These workers share the characteristic that they are jobless and desire work if there were available vacancies. They are however separated by the statistician on other grounds.

Second, we can define a category that involves sub-optimal employment relations. Workers in this category satisfy the ILO criteria for being classified as employed but suffer “time related underemployment”.

For example, full-time workers who are currently working less than 35 hours for economic reasons or part-time workers who prefer to work longer hours but are constrained by the demand-side.

Sub-optimal employment can also arise from “inadequate employment situations” where skills are wasted, income opportunities denied and/or where workers are forced to work longer than they desire.

Unemployed

According to ILO concepts, a person is unemployed if they are over a particular age, they do not have work, but they are currently available for work and actively seeking work. Unemployment is defined as the difference between the economically active population (civilian labour force) and employment.

The inference is that the economy is wasting resources and sacrificing income by not having the unemployed involved in productive activity.

There are, however, other avenues of labour resource wastage that are not captured by the unemployment rate as defined in this manner. The persons represented in these other avenues of resource wastage may be either in or out of the labour force.

Underemployment

Underemployment may be time-related, referring to employed workers who are constrained by labour demand to work fewer hours than they desire, or to workers in inadequate employment situations, including skill mismatch. If society invests resources in education, then skills developed should be used appropriately. However, it is very difficult to quantify this wastage.

Time-related underemployment is defined in terms of an individual who is willing to work additional hours, is available to work additional hours, but is unable to find the desired extra hours.

An economy with rising underemployment is less efficient than an economy which meets the labour preferences for working hours. In this regard, involuntary part-time workers share characteristics with the unemployed.

A part of an underemployed worker is employed and a part is unemployed, even though they are wholly classified among the employed.

Marginally attached workers and others outside the labour force

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, which works within the same framework as Eurostat:

Persons not in the labour force are considered to be marginally attached to the labour force if they:

- wanted to work and were actively looking for work but were not available to start work in the reference week …

- wanted to work and were not actively looking for work but were available to start work within four weeks …

From a statistical consideration, discouraged workers (also called hidden unemployed) are classified as being not in the labour force. The international guidelines from the ILO suggest, however, that for persons not in the labour force, the relative strength of attachment to the labour market be measured.

From the perspective of underutilisation, the issue is whether those classified as being out of the labour force have characteristics similar to those who are classified as being in the labour force but unemployed.

It is clear, that discouraged workers are a sub-group of the marginally attached. They want to work and are available for work (under the same terms as the unemployed) but believe that search activity is futile given the depressed labour market.

The discouraged worker is thus more like the unemployed worker than they are, for example, like a retired person or a child in full-time education.

Further, if we extended our definition of the relevant time-frame to four weeks from the current week, the picture would change rather dramatically. We would substantially increase the number of marginal workers who shared essential characteristics (wanted to work, available to work) with the unemployed.

The ECB analysis recognises that to accurately measure labour market slack “wider definitions” of underutilisation, as discussed above are essential.

They consider the extent to which workers are classified as inactive but are likely to re-enter the labour market if employment growth improves.

In this category, they note that “31⁄2% of the euro area working age population are marginally attached to the labour force – that is, categorised as inactive, but simply competing less actively in the labour market”.

These workers include the discouraged workers – reflecting the poor employment growth and the need to preserve self-esteem by giving up searching for work that isn’t there.

The ECB note that the discouraged workers:

… can be relatively quick to rejoin the labour force as labour market conditions improve.

They also note that “a further 3% of the working age population are currently underemployed (i.e. working fewer hours than they would like)”. We have discussed this group earlier.

The question then is what would the labour market underutilisation rate be if these sources of slack were added to the official unemployment rate.

The ECB provide the following graph (their Chart C) to show the time-series movements in the four underutilisation categories (unemployment, available, but not seeking work, seeking work, but not available, and underemployed).

What is striking is that even before the GFC struck, broad labour underutilisation was around 15 per cent in the Euro area, indicating that the monetary union in good times is not a functioning system.

The ECB conclude that:

Combining the estimates of the unemployed and the underemployed with the broader measures of unemployment suggests that labour market slack currently affects around 18% of the euro area extended labour force … This amount of underutilisation is almost double the level captured by the unemployment rate, which now stands at 9.5% … As well as suggesting a considerably higher estimate of labour market slack in the euro area than shown by the unemployment rate, these broader measures have also recorded somewhat more moderate declines over the course of the recovery than the reductions seen in the unemployment rate.

In other words, the situation is much worse than is indicated by the official unemployment rate.

And, the ‘recovery’ is not eating into these broader measures.

The ECB notes that in most Eurozone nations, the broader labour market underutilisation measure has increased during the recovery (against the decline in Germany).

They note that “In France and Italy, broader measures of labour market slack have continued to increase throughout the recovery, while in Spain and in the other euro area economies, they have recorded some recent declines, but remain well above pre-crisis estimates.”

While this is a new way of viewing the data in the European context, broader measures of labour underutilisation have been around for a long time in say Australia and the US (U-1 to U-6).

My own research group in Australia pioneered an hours-based measure of labour underutilisation 20-odd years ago (our CofFEE Labour Market Indicators), which have since been discontinued after the Australian Bureau of Statistics took up the challenge and started to publish similar indicators in recent years.

We figured the ABS had more resources to do this work and our series tracked their series closely so we abandoned our publications – see CofFEE Labour Market Indicators – to access our archive.

The ECB insights have two consequences:

1. Wages growth will remain at depressed levels which further increases poverty rates (I note a report released yesterday showed that a “Record 60% of Britons in poverty are in working families” – (Source).

2. The flat wages growth means that recovery in domestic demand will be attenuated, which then creates a vicious cycle – slow employment growth, rising labour underutilisation, flat wages growth, and so on.

My own research has clearly shown that underemployment is becoming a new scourge in this neo-liberal era and acts as a strong brake on wages growth independently of unemployment (the traditional wage suppressant).

Conclusion

So for all your Europhiles (and Eurozone supporters) out there, tell me that this is a success story!

We are now nearly a decade into the crisis. The measures of economic prosperity remain in an appalling state. Many remain below the pre-crisis levels.

The breakouts of the crisis are not evident.

The Eurozone is creeping along – locked into a malaise that will persist for many years to come – and then worsen as the next cycle hits.

The monetary union has been a disaster and despite all the current talk about Macron and Spain calling for a fiscal union and Eurobonds and all the rest of the banter that comes out of Europe – don’t expect much to change any time soon.

Meanwhile tens of thousands the youngsters have become adults and have never worked nor gained any meaningful work experience.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Meanwhile yesterday the European Commission decided to take Portugal out of the excessive deficit procedure. This has been hailed by the Portugues Left as a victory. The Spanish Left is showcasing the effectiveness of Portugal’s left-wing government while Spain is not complying with the deficit targets under a Conservative government. This shows the extent to which the Left has become captured by Neoliberal thinking. Portugal’s rate of unemployment remains at 10% -very far from full employment. The target of the EU is to reduce the structural deficit, which currently stands at -2%, by 0.5% of GDP every year. The position of the European so-called progressive parties is a total disgrace. With a 10% rate of unemployment -who knows what the U6 measure would be- it is outrageous that the Lef is not clamoring for an increase of the Portuguese deficit.

Bill, one could well be an EUphile and a Europhobe simultaneously without contradiction.

I might suggest that youth unemployment would be even higher if it were not that large quantities of them have come here to the UK. That ought to be factored into the figures.

“The monetary union has been a disaster . . . ”

A deliberate disaster?

‘The European Central Bank (ECB) crossed the line into improper political activity during the Eurozone crisis, according to a report by anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International.

Actions, including former ECB President Jean Claude Trichet’s controversial secret letters to the late Brian Lenihan ahead of the Irish bailout in 2010 and letters to the governments of Spain and Italy insisting that support for banks was linked to policy actions, were cited in the report.

Transparency International found that the ECB’s institutional independence gave the bank “an extraordinary degree of latitude.” It said the organisation should be more answerable, and recommended that the ECB no longer form part of the Troika overseeing bank bailouts.

In a statement the ECB, which cooperated with the original research, said steps had been taken since the crisis to “further enhance its transparency, accountability and integrity mechanisms.” ‘

At least the Eurocrats dreams are still alive and surely blighting the lives of a generation or two is a price well worth paying for that!