It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

If Africa is rich – why is it so poor?

When I was a student, that is, formally studying for degrees rather than the constant-learning approach which makes us permanent students, I was very interested in development economics and have carried that into the career phase of my work, including doing commissioned work for international agencies in Africa and Asia. One of the things I have come up against in that work has been the question of why are the nations in Africa, for example, so poor, when it is obvious to all and sundry that they possess massive resource wealth. My student days introduced me to dependency theory, which provided a solid framework for understanding the nature of underdevelopment. It stood in contrast to the mainstream development theory that was presented in most textbooks and which we would now call the neo-liberal approach. That approach is publicly enunciated by the IMF and the World Bank as if it is reality. In fact, it is a chimera! The framework of development aid and oversight put in place by the richer nations and mediated through the likes of the IMF and the World Bank can be seen more as a giant vacuum cleaner designed to suck resource and financial wealth out of the poorer nations either through legal or illegal means, whichever generates the largest flows. So while Africa is wealthy, its interaction with the world monetary and trade systems, leaves millions of its citizens in extreme poverty – unable to even purchase sufficient nutrition to live. It is a scandal of massive proportions and should become the target of all progressive governments (as they emerge).

Over the weekend, I watched a short documentary produced by France24 (published June 16, 2017) – Modern-day slaves: Europe’s fruit pickers .

It is a disturbing account of how the higher income groups in Europe enjoy a lifestyle that is made possible by the harsh and illegal exploitation of low wage workers in Spain and Italy. The specific study is the fruit industry which supplies fresh fruit into northern Europe to the enjoyment of consumers but under horrific conditions for the manual (mostly migrant) workers who do the labour.

When I was a postgraduate student, a friend (also a student) and I organised what we rather obviously billed as a Radical Film Festival.

We found an archive of films that we could get for free held by the Victorian State Library. There were several films available some of which featured labour conditions and attacks on trade unions in nations run by right-wing regimes in Latin America.

One film – Chircales (The Brickmakers) released in 1972 – focused on the life of an impoverished family of non-unionised brick makers in the outskirts of Bogotá.

It showed how the workers were exploited to enrich the elites and then how the family was forced out by the capitalist when the husband became ill as a result of years of working in unsafe conditions. The final scene of the family (wife and several kids) walking out of the digging to nowhere dragging a picture of the virgin mary is still indelibly etched in my mind.

Another film we showed focused on the low-wage tin miners of Bolivia and the way their attempts at unionising were crushed by the capitalists aided and abetted by the power of the state police and military.

We used to have a discussion at the end of each film. At the end of that particular film someone in the audience said it was all well and good to expose exploitation in poor nations but in Australia our labour laws prevent that sort of thing so what was the relevance of the film ffor us.

I posed the question in response: Who in the audience has ever bought a tin of canned food or drink?

The France24 film brings the same issues into relief again. The better life that many enjoy comes at the expense of other workers on low-wage and living in precarious conditions and being horrendously exploited by one capitalist or another.

It brought back further memories of my postgraduate days.

As a student I also became interested in the work of German academic Andre Gunder Frank, who was supervised in his doctoral studies at the University of Chicago by Milton Friedman.

In his later body of work, Gunder Frank was a fierce critic of the free market approach espoused by the Chicago Boys (Friedman’s collection of doctoral students most noted for the damage they did in Chile after the overthrow of Salvatore Allende in 1973 by Pinochet.

The first book from Gunder Frank that I read was his 1967 Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, which built on the earlier work (1949) by the Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch and German economist Hans Singer.

The Prebisch-Singer Thesis became the basis of Dependency theory – a distinct framework for understanding the process of economic development.

Their thesis challenged the traditional neo-classical development theory (which originated from David Ricardo’s notions of comparative advantage) and conjectured that the terms of trade moved against poorer nations without an industrial base in favour of richer industrial nations.

In other words, the world prices of primary commodities (agriculture etc) declines over time relative to the price of industrial goods, which increases income and wealth inequalities across (and within nations).

The policy implications, pushed by the authors, included recommendations that the development process should begin with the creation of a import-competing manufacturing base.

The traditional theory of economic development (modernisation theory) suggested that nations follow a pattern where they begin as undeveloped and primitive societies and through industrialisation (investment, adoption of best-practice technology) and institutional and governance development, begin to operate like developed nations.

A middle class forms and incomes grow. An export-orientation is then encouraged to plug the nation into the world economy

Dependency theory extends that work and posits that the nations that we now consider to be developed were never ‘undeveloped’ in the way we view nations in, say, Africa.

Rather, the nations that are called undeveloped have a unique role in the world system unlike anything that the rich countries have ever played.

Whereas the mainstream view is that Africa, say, is poor, and interventions are required to make it rich.

But dependency theory would consider Africa to be ‘rich’ and those riches are being continually drained to the benefit of the core wealthy nations.

Dependency theory posits that resource flows are from periphery to the core rather than the other way around. The rich nations do not ‘invest’ in the ‘income poor’ nations to make the latter richer.

Rather, the rich nations set up processes (supported by international institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank) to ensure that resources flow to the benefit of the advanced world.

These processes, which include legal frameworks and tax rules, privatisation, and the imposition of fiscal austerity to suppress public good development, undermine the opportunities of the ‘income poor’ nations to use their own resource riches to their own advantage.

In his September 1966 Monthly Review article – The Development of Underdevelopment – (this link is to a reprint that appeared in a later collection), which was a precursor to his 1967 book, Gunder Frank wrote:

… our ignorance of the underdeveloped countries’ history leads us to assume that their past and indeed their present resembles earlier stages of the history of the now developed countries. This ignorance and this assumption leads us into serious misconceptions about contemporary underdevelopment and development …

It is generally held that economic development occurs in a succession of capitalist stages and that today’s underdeveloped countries are still in a stage, sometimes depicted as an original stage, of history through which the now developed countries passed long ago. Yet even a modest acquaintance with history shows that underdevelopment is not original or traditional and that neither the past nor the present of the underdeveloped countries resembles in any important respect the past of the now developed countries. The now developed countries were never underdeveloped, though they may have been undeveloped. It is also widely believed that the contemporary underdevelopment of a country can be understood as the product or reflection solely of its own economic, political, social, and cultural characteristics or structure. Yet historical research demonstrates that contemporary underdevelopment is in large part the historical product of past and continuing economic and other relations between the satellite underdeveloped and the now developed metropolitan countries. Furthermore, these relations are an essential part of the structure and development of the capitalist system on a world scale as a whole.

Note his use of the term ‘underdevelopment’ as opposed to undeveloped.

Essentially, Gunder Frank argued that it is essential to understand the relationship between the “metropolis and its economic colonies” under capitalism.

The underdeveloped countries were in that state because they were functionally essential to making the developed nations at the core richer.

This was a very conception of the process of economic development that organisations such as the IMF and the World Bank hold out as they impose neo-liberal policy structures onto the underdeveloped world.

What Gunder Frank argued was that these policy structures were not about developing the undeveloped nations but, rather, developing the richer nations further and holding the underdeveloped nations in a state where they could act as resource conduits for the richer nations.

Along the way, the underdeveloped nations will develop a middle class and a localised upper class but they only serve to drain the resources in favour of the richer nations even more efficiently.

Gunder Frank said that the underdeveloped nations serve “as an instrument to suck capital or economic surplus out of … [the] … satellites and to channel … this surplus to the world metropolis”.

He also eschewed the use of export-oriented development – that favoured by the World Bank and the IMF – believing that it destroyed the local subsistence systems and accelerated the transfer of surpluses to the core while leaving the peripheral economies heavily indebted and in precarious states.

I was thinking about all this when I read a recent report about the way the richer nations are draining, with IMF and World Bank support, the riches of Africa and leaving the African nations with poor quality public infrastructure, on-going high levels of poverty and precarious states of debt dependence.

The report (released May 2017) – Honest Accounts 2017 – was put out by Global Justice Now in coalition with a number of partners, and is quite shocking to read.

It begins by reminding us that:

Africa is rich – in potential mineral wealth, skilled workers, booming new businesses and biodiversity. Its people should thrive, its economies prosper. Yet many people living in Africa’s 47 countries remain trapped in poverty, while much of the continent’s wealth is being extracted by those outside it.

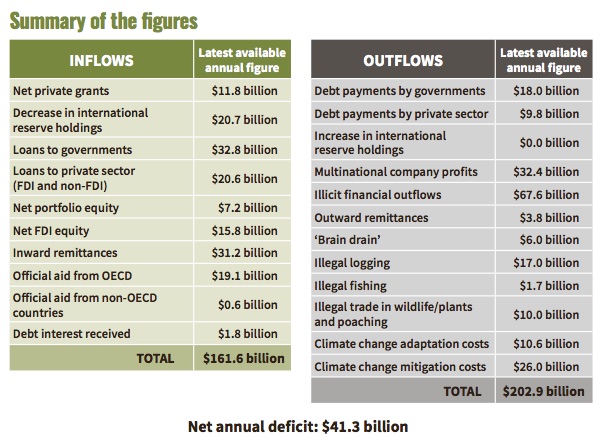

The aim of the study is to calculate “the movement of financial resources into and out of Africa and some key costs imposed on Africa by the rest of the world.”

The principal finding is that:

We find that the countries of Africa are collectively net creditors to the rest of the world, to the tune of $41.3 billion in 2015 … Thus much more wealth is leaving the world’s most impoverished continent than is entering it.

The following graphic from the Report provides a summary of the financial flows:

The methods of surplus extraction are many and varied:

1. Repatriation of profits.

2. Illegal financial outflows (smuggling).

3. Transnational companies “deliberately misreporting the value of their imports or exports to reduce tax”.

4. Debt and interest repayments “with the overall level of debt rising rapidly”.

5. Valuable resources “being stolen from Africa in illegal logging fishing and the trade in wildlife/plants”.

6. “trade policies mean that unprocessed agricultural goods are often exported from African countries and refined elsewhere, causing the vast majority of their value to be earned abroad.”

The richer countries also impose costs on Africa in other ways.

1. “the cost to African countries of adapting to climate change: a process which has been overwhelmingly caused by richer industrialised and industrialising countries, not Africa – amounting to $10.6 billion a year”.

2. “the cost to Africa of mitigating climate change – to reorient African economies onto a low carbon path – again due to the need to tackle climate change: the annual cost here is even greater, at $26 billion.”

The point that “Africa is not poor” but “many people in African countries live in poverty” cannot be overemphasised.

I recall when was doing field work in South Africa a few years ago I had some dealings with the South African Treasury and the IMF.

The issue related to my argument that the Expanded Public Works Program should be expanded dramatically to resemble a demand-driven employment guarantee rather than a supply-driven (financially constrained) program with limited coverage.

The nation at the time was running fiscal surpluses even though there were more than 12 million people living in extreme poverty (about 22 per cent of the population) – which means they are unable to pay for basic nutritional needs, much less housing and health care.

Around 35 to 37 per cent of the population cannot purchase essential non-food items.

And around 55 per cent have enough to eat but are considered poor by the usual standards (which I might add are ridiculously low).

Anyway, I recall one Treasury official pounding the table at a discussion saying “how can we afford to expand the scheme”.

I responded by noting that South Africa was not only a currency-issuing state but was among the richest nations in the world in terms of real resources.

So how could it not afford to bring more of those resources into productive use and lift more people out of poverty.

The IMF official claimed that the state had to continue running surpluses because they had to ensure they could meet their international debt obligations.

At that point, I could hear that giant sucking sound as the financial and real resources were being vacuumed out of the nation to the benefit of those elsewhere, with some leaking down to the local officials that had been co-opted by the likes of the IMF and the World Bank and acted, more or less, as their agents.

And, as this was post apartheid, I am, of course, referring to the newly empowered black elite here.

The Global Justice Report makes it clear that:

1. “Africa is generating large amounts of wealth and, in some ways, is booming.”

2. “The value of mineral reserves in the ground is of course even larger – South Africa’s potential mineral wealth is estimated to be around $2.5 trillion …”

3. “Companies are anyway easily able to avoid paying the taxes that are due, because of their use of tax planning through tax havens. Many African tax policies are the result of long standing policies of Western governments insisting on Africa lowering taxes to attract investment.”

4. “Corporations stealing wealth”.

5. “Africa’s poverty is much deeper than the World Bank likes to publicise … and rising …”

The question is what can be done about this?

First, fundamental reform of the international institutional structure is required including the disbanding of the IMF and the World Bank, both institutions that serve to facilitate these surplus movements from poor to rich.

Developing countries seeking finance from the IMF and the World Bank have been forced to adopt neoliberal policies that included harsh austerity measures – similar to the ones being imposed today on the periphery countries of the eurozone today – as a condition of international support.

The programmes of structural adjustment and austerity imposed by the IMF on developing countries in the 1980s and 1990s undermined many of the achievements of the previous growth model, driving living standards down and poverty levels up.

By the mid-1990s, no less than 57 developing countries had become poorer in per capita income than 15 years earlier – and in some cases than 25 years earlier. In almost all countries where austerity-driven policies were imposed, poverty and unemployment grew, labour rights deteriorated, inequality soared, and financial and economic instability increased.

In our upcoming book, we outline the fundamental Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) insight that the ultimate constraint on prosperity is the real resources that a nation can command, which includes the skills of its people and its natural resource inventory.

If a country’s resource base is very limited, there is relatively little that a country can do to pull itself out of poverty even if the government productively deploys all the resources available to the nation.

These countries may find no market for their currencies and may be forced to trade in foreign currencies.

In this sense, it should be noted that not all currencies are equal.

However, this is not a balance-of-payments constraint as it is usually intended. It is a real resource constraint arising from the unequal distribution of resources across geographic space and the somewhat arbitrary lines that have been drawn across that space to delineate sovereign states.

The world must take responsibility to ensure that it alleviates any real resource constraints that operate through the balance of payments.

Imposing austerity on these countries is no solution. The evidence shows that the so-called structural adjustment program (SAPs) that the IMF and World Bank typically impose on poor nations struggling with balance-of-payments problems – based upon fiscal austerity, elimination of food subsidies, increase in the price of public services, wage reductions, trade and market liberalisation, deregulation, privatisation of state-owned assets, etc. – have had a disastrous social, economic and environmental impact wherever they have been applied.

Not only have they kept millions in persistent poverty but they also foisted unsustainable levels of external debt on these nations, which were then used to justify the imposition of destructive export-led production strategies that in many cases devastated the existing subsistence systems and led to large-scale environmental ruin (for example, massive deforestation in Mali).

Though masqueraded as development programs, SAPs have actually acted as giant siphons, sucking out wealth and resources from these countries and pumping it into the pockets of the rich elites and corporations in the US, Europe and elsewhere.

To add insult to injury, in many instances these policies also wrecked the borrowing countries’ local productive sectors, thus creating increased import and debt dependencies.

Clearly, the IMF and the World Bank have outgrown their original purpose and have ceased to play any positive role in the management of world affairs.

Rather, their interventions have undermined prosperity and impoverished millions of people across the world, and continue to do so – mostly, but not exclusively, in the developing world (as the Fund’s participation in Greece’s bailout program testifies).

In this context, we argued that a new multilateral institution (or series of institutions) should be created to replace both the World Bank and the IMF, charged with the responsibility of ensuring that these highly disadvantaged nations can access essential real resources such as food are not priced out of international markets due to exchange rate fluctuations that may arise from trade deficits.

There are two essential functions that that need to be served at the multilateral level:

- Development aid – providing funds to develop public infrastructure, education, health services and governance support.

- Macroeconomic stabilisation – the provision of liquidity to prevent exchange rate crises in the face of problematic balance of payments.

A progressive developmental model should reject the current export-led corporate farming models, which are implicated in environmental degradation within less developed countries.

A progressive multilateral institutions would aim to reduce (and ultimately eliminate) poverty through economic development but within an environmentally sustainable frame.

It would also allow countries to restrict imports from nations that engage in poor environmental practices – an approach that the WTO has repeatedly deemed illegal.

Further, developing nations should have the right to defend and sustain their local industries. Contrary to the claim that trade liberalisation promotes growth, the evidence indicates a positive relationship between tariffs and economic growth in developing economies.

We also showed earlier in the book that no advanced nation achieved that status by the following the IMF/World Bank free market approach; rather, it did so through widespread industrial protection and government controls and supports.

This observation is consistent with Gunder Frank’s thesis noted above.

A progressive trade policy would also ban the Investor-State Disputes Settlement (ISDS) clauses embedded in the more recent wave of trade agreements and force corporations to act within the legal constraints of the nations they seek to operate within or sell into.

Under a fair trade framework, all countries should respect the following principles:

- Good working conditions – wages, safety, hours.

- Right to association and to strike – formation of trade unions, etc.

- Consumer protection – safety, ethical standards, quality of product or service, etc.

- Environmental standards.

To this end, the WTO should be replaced by an all-encompassing multilateral body that is charged with establishing relevant labour and environmental standards to regulate trade.

A progressive policy framework has to allow all workers access to work, and the poorest members in each nation opportunities for upward mobility, if jobs are destroyed as part of an overall strategy to redress matters of global concern (whether to advance labour, environmental or broader issues).

Part of these transition arrangements might also include more generous foreign aid to ensure that trade constraints do not interrupt international efforts to relieve world poverty.

In general, a single nation should not be punished for the uneven pattern of geographic resource distribution.

With regard to the question of macroeconomic stabilisation – that is, the provision of liquidity to countries struggling with balance-of-payments problems – a progressive multilateral institution would recognise that all nations should maintain sovereign currencies and float them on international markets but at the same time acknowledge that capital flows may be problematic at certain times and that some nations require more or less permanent assistance due to their limited export capacities and domestic resource bases.

The starting point would be to recognise that as long as there are real resources available for use in a nation, its government can purchase them using its currency power. That includes all idle labour.

So, there is no reason to have involuntary unemployment in any nation, no matter how poor its non-labour resources are. The government in each country could easily purchase these services with the local currency without placing pressure on labour costs in the country.

A new multilateral institutional structure should work within that reality rather than use unemployment as a weapon to discipline local cost structures.

Furthermore, new international agreements are needed to outlaw speculation by investment banks on food and other essential commodities.

A new framework is needed at the international level to ban illegal speculative financial flows that have no necessary relationship with improving the operation of the real economy.

Finally, the multilateral institution would not force nations to cut taxes for high income-earners in return for aid, which is another bias in current IMF and World Bank interventions.

It would recognise that the role of taxation is to create non-inflationary space for the sovereign government to command real resources in order to fulfil its socio-economic program.

The reality is that there are many idle resources in the poorer nations – land, people and materials – that can be bought by government and mobilised to reduce poverty without causing inflation.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that these nations will likely have to run continuous fiscal and current account deficits for many years to allow the non-government sector to accumulate financial assets and provide a better risk management framework.

A progressive international agency would help them to do just that.

Conclusion

The agenda outlined above would go a long way to break the core-periphery dependence model that keeps resource rich nations such as those in Africa in poverty.

It would also force a major rethink in the core economies because they would have to generate their own riches without easy access to those in the now poorer (but resource rich) nations.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

In 1960, the total population of the African continent was 230 million. Today, it is more than 1.2 billion. We can’t really say that Africa is very densely populated because it has an area of 30 million km², while India, with roughly the same population, has an area of 3.3 million km², only 11% of Africa’s area. Of course, a lot of African territory is covered by deserts or semi-deserts.

What makes the demographic situation of Africa worrisome is not so much the size of the population but rather its rapid increase. Fertility in Africa remains very high despite a drastic decrease in mortality. Can anyone seriously believe that part of Africa’s food-supply problems don’t stem from its rapid demographic growth? If the population doubles every 25 -30 years, then food production has to increase rapidly as well. Otherwise food imports have to increase, which means less foreign exchange available for the import of investment goods, indispensable for growth.

The net outflow of 41.3 billion is 34 per African. It can hardly be regarded as a big factor.

Regards. James

@James:

I would think that population is rather tangential to the main issues Bill has so cogently argued. One of the factors also driving high population growth in under developed continents such as Africa is that high infant mortality caused by poverty and unhealthy living conditions impel parents to have more children than they otherwise would as they fear one of more of their children will not make it to adulthood. If there is no provision for old age children would likely be able to support their parents.

On the subject of food and Africa, from LRB (June 2017) comes The Nazis Used It, We Use It, wherein Alex de Waal speaks of the return of famine as a weapon of war in equatorial black Africa.

Dear Barri

Infant mortality is no longer very high in Africa. It is 87/1000 in Chad, 50/1000 in Ethiopia, and 68/1000 in Mozambique. It is precisely because infant and child mortality are no longer high while fertility remains very high that population is growing so fast in Africa.

In an African country, the replacement fertility is above 2.1, but not by that much. Let’s take Ethiopia as an example. Its infant mortality rate is 50/1000. Let’s assume that the child mortality rate is also 50/1000. That means that of every 100 females babies born, 90 will reach reproductive age. Of 1000 babies born, about 485 will be female. If 90% of those reach reproductive age, then the replacement fertility rate is 2.29, 1000 ÷ (485 × 0.9) = 2.29. The actual fertility rate of Ethiopia is 5.07, which is 2.21 times the replacement rate. This means that, if the current combination of fertility and mortality continues, each generation in Ethiopia will be 2.21 times larger than the previous one. That makes for very fast population growth.

We shouldn’t be reductionistic about this, but I find it highly plausible that Africa’s rapid population is a hindrance to its development. Those who are well-intentioned toward Africans should not refrain from emphasizing the extreme importance of a rapid reduction in fertility to bring demographic growth under control.

Regards. James

We talk about civilisation; but what civilisation is there really in this world?

The strong smarter exploit the weak and not so smart at the base level of society, and this goes on within countries, and then strong and clever countries exploit the weaker and not so clever countries.

Institutions like IMF and WTO are used as a tool to keep this exploitation to go on; and what do we have the UN for? They are just what one workmate told me in german,”a Quatschkammer”.

The population explosion also cannot go on forever.

We in Australia may be called a lucky country, but how will our children be; if China and India decides to flood the country with their people, they’ll hardly miss 20 or more millions, and take over the running of the country, which will also be like a third-world-country.

Do we have any politicians who will not bend to the will of the voters? In Africa the biggest problem is probably corrupt governments, supported by the rich of the developed world.

It’s so easy to blame the Africans and argue they are in a Malthusian poverty trap.

Development is the way out of that trap. The point is Africa has been denied the opportunity to develop.

All the scandalous horrors revealed here are hidden from view in the rest of the world. One might idly wonder why Africa seems so backward and make racist conclusions to justify it. The only reason I was aware of it is because I became interested in economics when I found out about the web of lies spun by politicians and the rentier class and decided I needed to know the real picture. Then I was directed to MMT, which was a great leap forward.

Also I came across this talk by John Perkins. “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oARBdBtGenM. This made manifest the machinations Bill illustrates here.

It really is very important we understand a lot of our affluence is built on extracting assets and resources from the Third World. It’s still colonialism, but the empires that exercise it are financial, with military muscle to enforce it.

To James Schipper.

I would have thought that ’emphasising the importance of a rapid reduction in fertility’ would only be seen to be fruitful when the parents see that their children are now surviving, thus less children would be needed to take care of their parents?

Yes the parasites who feast on their much larger host. Here is an illustration of the moral redundancy of those running the horror show :

DATE: December 12, 1991

TO: Distribution

FR: Lawrence H. Summers

Subject: GEP

‘Dirty’ Industries: Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging MORE migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [Less Developed Countries]? I can think of three reasons:

1) The measurements of the costs of health impairing pollution depends on the foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality. From this point of view a given amount of health impairing pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages. I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.

2) The costs of pollution are likely to be non-linear as the initial increments of pollution probably have very low cost. I’ve always though that under-populated countries in Africa are vastly UNDER-polluted, their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City. Only the lamentable facts that so much pollution is generated by non-tradable industries (transport, electrical generation) and that the unit transport costs of solid waste are so high prevent world welfare enhancing trade in air pollution and waste.

3) The demand for a clean environment for aesthetic and health reasons is likely to have very high income elasticity. The concern over an agent that causes a one in a million change in the odds of prostrate cancer is obviously going to be much higher in a country where people survive to get prostrate cancer than in a country where under 5 mortality is is 200 per thousand. Also, much of the concern over industrial atmosphere discharge is about visibility impairing particulates. These discharges may have very little direct health impact. Clearly trade in goods that embody aesthetic pollution concerns could be welfare enhancing. While production is mobile the consumption of pretty air is a non-tradable.

The problem with the arguments against all of these proposals for more pollution in LDCs (intrinsic rights to certain goods, moral reasons, social concerns, lack of adequate markets, etc.) could be turned around and used more or less effectively against every Bank proposal for liberalization.

https://www.counterpunch.org/1999/06/15/larry-summers-war-against-the-earth/

It boils down to politics and societal organization. Island and Denmark is small orderly, well organized welfare countries without extraordinary raw material resources. Of course, it helps to be in the western hemisphere.

Nigeria did have a population of ~25 million in the 1930s, today it’s 180 million and UN prognosis is that it by +2050 will be the worlds third most populous nation with +800 million. That is a lot of folks.

To revolt against the IMF/WB neoliberal order would risk a poor country to be an outcast and sanctioned in some way. And the local “gangsters” that willingly will go in lockstep with IMF/WB is abundant. All to easy to divide and rule.

There is a need for nationalistic cohesion and social capital. It did take the French revolution to change the course in Europe. When the reports did come in of the nobles’ heads rolling in droves in France, all over Europe then what had been unthinkable power sharing was suddenly a “healthy” option. But real revolutions is rare events.

One Nigerian guy that used to comment on Medialens, had some reflections on the then (2005) popular curse of Africa, corruption:

https://justpaste.it/1810a

Corruption isn’t the cause of African Underdevelopment

Why do countries in Africa (and eg the Caribean) have government debt denominated in USD rather than in their own local currencies? Isn’t that a root cause of much of the problems they suffer?

“Why do countries in Africa (and eg the Caribean) have government debt denominated in USD”

The leaders are persuaded to do so. It’s always easier to go the debt route than to do things the hard way. And once they’ve got you, they’ve got you.

They don’t have the advisors who would tell them to play each country off against the other for access to your supply of consumers for their products. The one that gets the import licence would be the one prepared to exchange goods on the most favourable terms and preferably discount your currency for their own.

“Why do countries in Africa (and eg the Caribean) have government debt denominated in USD”

Probably complex, but it’s developing countries that have had the need to import to develop. If they can’t pay it all with export they need to borrow in international accepted currency.

Then there was real negative interest rates international, in the second half of 70s. Paired with soaring prices on developing countries raw materials. The wobbly USD was rock bottom. Sort of misconduct to not borrow.

Some abuse by the developing worlds elite, especially Latin America, the money bounced to the elites off shore accounts while the debt bill stayed with the masses. But not all, many did do what they could to develop, maybe not all so sound but they tried.

Then Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker to Fed and he raised interest rates to loan shark levels. The dollar started to raise and raw material prices did crash. As the Mexican CB chief said, he had his waiting room full of international banker how wanted to lend, the next day after Volcker raised interest rates the waiting room was empty.

And the world got the third world and eastern European debt crisis, they all got in the hands of IMF & WB who dictated the Washington consensus model for their economies. They got restrictions on especially creating CB money. And the main economic expertise is neoliberal Chicago boys.

Modern history tends to forget that e.g. the Yugoslavia break up and the terrible regime of Nicolae Ceausescu in Romania had its root in IMF & WB debt pay back mandates.

I think that countries may have to borrow in a foreign currency sometimes even for legitimate reasons. MMT says that a currency issuing country can always afford to purchase anything that is for sale in that currency and that it will not be necessary for them to even borrow in their own currency if they don’t want to. However, there may be many items (like jet airplanes) and services that some countries just do not have the resources to produce for themselves. Foreign suppliers of these products may have no interest in exchanging them for the local currency. So in effect those products are not for sale in that currency, and if that country wants them, they will have to acquire the currencies that the supplier will accept. Or develop the capability to produce those items themselves.

MMT by itself does not offer a solution to all impoverished resource limited countries, which is why much of this article makes a moral argument that more developed wealthier countries should stop taking advantage of the countries in Africa and instead do the right thing and actually help them out. It is a good argument.

James Schipper,

I think what you are describing is a textbook Demographic Transition. When a country gains access to technologies that reduce their death rate; naturally, the transition dramatically increases the population because mortality rate drops–while people there are still operating under the high birth scheme to adapt to high death situation that they had.

Yes, it is a problem. Yes, we should acknowledge it. No, I don’t think it is unmanageable. You can’t deny that the IMF and world bank makes the transition difficult.

Going back to the scope of this blog post, I sense a bit of victim-blaming in your comment. The argument is, “well if these Africans would stop multiplying like rabbits, we’d be fine. Fools didn’t think to increase food supply when populations rose.” Do they have adequate sex ed? birth control? I heard the pope was saying people shouldn’t use birth control. Education and adequate income make abortion and pregnancy go down. How can you pay for social program like those if you are constantly being bullied by spiritual leaders like the pope and the neoliberals to make you run budget surplus? How do you develop your nation when your returning students from oxford/harvard come back with all the neoliberal hogwash? If the rich and powerful can make half of USA citizens earn minimum wage (18.86 USD minimum wage if wage kept up with productivity), what do you think they can/will do to nations with rich natural resources but can’t guard themselves against these “elites”? Bill is saying that these Western countries interest primarily in enriching their own coffers rather than help make real meaningful change, maybe even try the do-no-harm thing.

I read in Bad Samaritan by Ha-Joon Chang that neoliberals from Western nations made African countries WORSE. As Bill pointed out, growth in many nations are worse than 15 years ago. Is it not fair to say that negatively impacts how the government in these nations will implement their social programs?

Solution is to pull these institutions out by the roots and correctly label mainstream economics as religious non-sense pseudoscience.

Stone,

Yes I think that’s part of it.

“Foreign suppliers of these products may have no interest in exchanging them for the local currency”

Yes they do. They won’t get the sale otherwise and they *are in competition* with other suppliers in the world from their own country and other countries.

Once again the analysis always takes the view that the rest of the world is some amorphous blob that acts with one mind – rather than millions of entities all in competition with each other for scarce demand.

The exporter will always try and get you to be in debt in their currency, but you just point out that you’ll talk to the other guy instead then. Then you’ll find a better offer suddenly appears on the table.

Search the internet. You’ll find loads of consultants from banks advising exporters of the benefits of local currency billing.

Neil Wilson, it might be true that Boeing Aircraft would be happy to accept the local currency of any country in the world in exchange for a 747. I just would be surprised if that is the case. They may be willing or they may not be willing, but that is for Boeing- not the currency issuing government to decide.

@Tom,

James focuses on population explosion, which is surely the major issue. He is not doing “a bit of victim-blaming”.

It is unhelpful to describe African population explosion as “a textbook Demographic Transition”. Nor is it helpful or correct to blame “neoliberal” institutions and governments.

You say: “Yes, it is a problem. Yes, we should acknowledge it. No, I don’t think it is unmanageable.”

Your propose:

– “pull these institutions out by the roots”

– “correctly label mainstream economics as religious non-sense pseudoscience”.

Unfortunately these ideas are almost meaningless phrases, little more than left-wing cant. They would have little or no impact on the problem.

The enormous difficulties cannot be ducked in this way. Instead, very vigorous birth control/reproductive health programs are imperative.

All available hands are needed to implement this – WHO, IMF, WB, EU, national governments, and even MMT!

But even then there are grounds for profound pessimistic about the next several decades.

@Neil Wilson

But the Boeing plane will most likely be priced in USD? The contract will be in USD enforceable une’er so called international law? They probably/maybe will accept payment in any tradable currency, that then is converted to another currency instrument depending on what short term yield it generate. I highly doubt that Boeing will write a contract in Venezuelan Bolivars.

When Sweden decided to develop to industrial nation by building railroads an canals in 19th century, the the finance minister Gripensted was accused of “flower talk” when he strongly argument that the money for it should be borrowed. He argued about the wonders of credit markets, any delay would cost lost income. While cabinet and parliament mostly wanted to save first. He got his way. I’ll guess the then unindustrialized country needed a lot of import for this. It’s estimated that Sweden had at least 60 years of negative current account due to this. But then nobody really cared about CC, it wasn’t calculated as today. A great bon was the German hyperinflation then most of the debt was in German marks.

So we industrialized with the help of foreign debt and increased domestic consumption. Rather the opposite of the neoliberal austerity model. Where you should like the household save first, then maybe consume, if your not dead by then.

It helped that already about 1840 mandatory schooling was enforced, a readymade workforce that could read and write. And it was just common practice to protect your own infant industry.

Kingsley Lewis,

Fine. I may have been to extreme.

Though I think it is funny that you still say WB and IMF (and even the EU) need to help when they are doing their best to loot African nations.

Many EU nations are choking under the euro.

Bill just wrote a blog saying they are the problem. You come around and say they are the solution.

To a degree you are right, if they change around their tendencies. However, reality is that they have no interest to help but loot.

Is it not important to ID a problem’s origin? I hate pussyfooting around. Neoliberals caused the problem. They get the blame, period. Stop dancing around.

Fact is African nations are growing slower when the unholy trinity (as Ha-Joon refer to them: IMF, WB, WTO) came to their aid and implemented free market stuff.

Until you kill the free market idea, people will be living in squalor.

My “solutions” were not for African nations, but neoliberal organizations. I proposed the same programs as you wrote in your comment.

I spent a long time living in Finland and I must say that what you wrote about the migrants fruit-picking in Western Europe definitely rings a bell in regards to how Finland exploits cheap immigrants and people from poorer countries to do its seasonal work for laughable wages and living in horrendous conditions while the country itself suffers from large unemployment. The whole situation is absurd and is getting worse.

The elephant in the room in both Bill’s article and replies above is the pervasive corruption that seeps into every aspect of African life from Cape Town to Cairo. True, foreign exploitation does nothing to help and only heaps economic woes upon others – but is there a hint of PC here that would not dare to blame Africans at any level for the mess that they find themselves in – but in reality it is not a matter of blame but of culture which is owned by Africa. One needs to look more closely at the reasons for corruption rather than entirely blaming neoliberal economics and foreign exploitation – the culture of Africa is basically tribal with traditions rooted in loyalties to clan and tribe. For example, the mixed race population in South Africa have little affinity with Africans at any level and in turn are excluded by African culture, seeing themselves allied more on the side of the white minority – though still suffering the poverty inflicted by apartheid so many years ago. It is true that Indian and “Coloured” communities joined the ANC revolution, but for the purpose of achieving their own rights, as did a handful of while communists who were sympathetic to the cause of fighting injustice. Although I have not lived in South America as I have in Africa, I have read that regardless of American exploitation and interference an underlying economic problem is quasi cultural, one of historical land ownership – Spanish colonists instituted feudal landownership in contrast to private ownership in the Anglosphere that has consequences to the present.

Rob Holmes, it seems like you’ve made up your mind. You have constructed a narrative which is going to be impervious to any arguments. Yes corruption is bad. I look at my own country- the US- and see it all around. Here the corruption is not rooted in tribal loyalties- no the culture here is worse- there is no loyalty at all except to money and power. Corporations buying votes with campaign contributions, hiring ex-legislators for six, seven figure salaries after they voted the right way. CEOs making $50 million in salaries and stock options for offshoring production and squeezing their workers. Millions of people languishing so a few thousands can make millions.

Yes the US is a wealthy country, the poor here are far better off than the poor in Africa. You don’t ever hear that corruption is causing people to starve here. No one ever says the Americans are tribal that’s why their society is so unequal. And no one says the US is getting screwed by stronger powers. It is a given that when the American people get robbed it is always by our own. And it happens all the time.

I realize that maybe you aren’t from the US and if not maybe the situation in your country differs somewhat. But where ever you live, keep in mind that sticking the blame on the poor for being poor is always pretty easy to do but not always right.

I’m still not understanding why a country would borrow in USD rather than in their own local currency. Let’s take that example of them wanting to by a Boeing airliner priced in USD. The African country could borrow in local currency (eg Nigeria Naira or whatever) and then exchange those Naira at the open market rate for USD and buy the plane. So purchase of a $320m Boeing 777 would be funded with 101billion naira of borrowing. The UK, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Japan, Switzerland etc etc governments buy USD priced imports using our local currency denominated government debt for funding after all.

Stone, why does a foreign exchange market exist in the first place? Foreigners need local currencies for one main reason as far as I can see- they want to import goods and services that are provided by that economy and are for sale in that local currency. There are a few other reasons such as needing spending money while visiting, or owing tax to that particular government for some reason, or desiring to save in a “harder” currency because they have no confidence in their own. But if a poor country has an economy that does not produce enough desirable products even for themselves and if it has few natural resources that foreign corporations can exploit, then there is not going to be much of a market for its currency. And if they were to attempt to sell large amounts of their currency so as to import products they need on whatever foreign exchange market does exist, the value of their currency is going to drop like a stone [sorry 🙂 ].

The countries you list, including Nigeria, all either have significant natural resources or produce desirable goods and services that can be exported. So there is a significant exchange market for their currencies. Most of them could buy a fleet of jumbo jets without destroying the market for their currency if they wanted to. Most of them could build their own jets if that is what they wanted to do. I doubt a country like Haiti would be able to do either. If Haiti wants a Boeing for some reason, it is going to have to come up with US dollars by either exporting goods that they already don’t have enough of, or by borrowing in US dollars. The Boeing Corporation can’t pay its employees or suppliers in Haitian currency, and its shareholders probably don’t want Haitian currency much either.

@ Stone

Money must be created, even if its out of thin air. If they create too much it’s value related to other currencies probably will drop, that could have negative effects for a poor country who is dependent on import. A rich industrialized country will of course have totally other margins in this than a poor developing country.

It’s a total different thing to create money to buy domestic resources for sale and to buy foreign currencies on the global market.

If e.g. Greece had had the Drachma foreign creditors probably had been much more cautious of the risk involved with a depreciating Drachma that had made it harder for Greece to service foreign debt.

Of course corruption in Africa is a huge problem, but the main problem is not what is usually implied. That it hampers “effective” local markets. The huge corruption problem is greedy gangster leaders that sell out their fellow Africans to foreigners fore some pieces of silver.

Australia is clearly an African country with the same fleecing of our wealth by the world’s capital controlling elites including some of our own and is not much better than South Africa. Under neo-liberal globalisation totally free trade policies the majority in many developed nations are being treated like the unfortunate African. Only the top few percent in Australia, the UK, the US and many other countries are really in the developed world while the remaining 95+% are now in the stagnating or ‘declining’ world?

Poor in this world suffer from financial exclusion. Growth requires that people are able to grow both sides of their balance-sheets – assets and liabilities, assets little bit more than liabilities. That in turn requires access to finance, to be able to invest in assets with borrowed money. Assets include production equipment but also things like housing stock. Investment process produces rising net wealth(because it creates three things: money, debt and the invested asset that has value), and hence, consumption, but also production structures to meet that consumption. And it all needs to be supported by suitable macro policies by the state (ie. running deficits) or it all comes to grinding halt sooner or later.

Banking plays a crucial role in all of that. Financial sector should be made to serve public purpose. China does it. Government there owns all banks, and it works.

Hepion I agree China runs it’s economy particularly well apart from the rampant real estate and share market speculation. They appear to understand the benefits of ongoing fiscal stimulus and their industrial and technological development policies are world beating. Their social policies are rubbish though. I put Australia’s governments for the last 30 years at the other end of the scale – totally hopeless, neo-liberal, monetarst, totally free trade destroyers of the economy except for financial services and mining/resources. Two ships heading in opposite directions? Same goes for the rest of the English speaking world unfortunately as far as running the economy.

@lasse But Nigeria does have USD denominated government debt. As you say, they export lots of valuable stuff (such as oil) that people elsewhere want to buy. Michael Hudson has talked about how his previous job was to assess what the export value of developing countries was and that then was used by banks when deciding what level of USD denominated debt to saddle those countries with. The aim was that the entire value of the country’s exports would go towards paying the interest on the USD denominated government debt and the developing country would get no goods or services in return for their exports.

Stone, my guess is that if a country decides it needs something that cannot be provided by its own people within its own borders, it has to come up with the means to convince a foreign supplier to provide it. Outside of force, that will generally be the currency the foreign supplier is willing to accept. One way to access that currency is through borrowing it and promising to repay it in that currency. I would agree that is not the optimal way if there are other options. And I have no doubt that often times there are other options. But some times there will not be. And sometimes even that option will not be available.