It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

A government can always afford high-quality health care provision

The Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based research foundation that analyses health care systems, recently released an interested international comparison of the performance of such systems across a number of criteria (July 2017) – Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care. Health care is one of several policy areas where the debate descends into fiasco because the typical application of mainstream economics obscures a widespread understanding of how the monetary system operates and the opportunities that system provides a currency-issuing government. Once an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is achieved the choices available in health care policy become more obvious and better decision-making is likely. The Commonwealth Fund report provides useful information in this regard, although the MMT understanding has to come separately.

I wrote about the US health care system some years ago (2010) in this blog – The US should have universal public health care. Not a lot has changed.

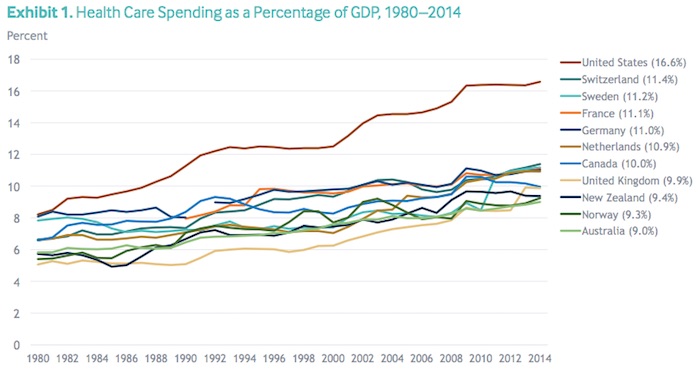

The Commonwealth Fund starts by showing that the US health care spending as a percentage of GDP is much higher than “other high income countries” and the gap between the US and the others has widened considerably over the last three or more decades.

Back in 1980, for example, the proportion of national income spent on health care in the US was around 8.1 per cent, comparable to Switzerland, Sweden, France and Germany.

By 2014, the US was spending 16.6 per cent of GDP on health care, compared to say 11.4 per cent by Switzerland, 11.2 per cent by Sweden, 11.1 per cent by France, 11 per cent by Germany, 10.9 per cent by the Netherlands, 10 per cent by Canada, 9.9 per cent by the UK, 9.4 per cent by New Zealand, 9.3 per cent by Norway, and 9 per cent by Australia.

The following graph (Exhibit 1 in the Report) tells the story.

One would expect that the health outcomes of Americans should be vastly superior given the extra resources that are being devoted to the quest.

Of course, we know that:

Yet the U.S. population has poorer health than other countries. Life expectancy, after improving for several decades, worsened in recent years for some populations, aggravated by the opioid crisis. In addition, as the baby boom population ages, more people in the U.S. – and all over the world – are living with age-related disabilities and chronic disease, placing pressure on health care systems to respond.

Timely and accessible health care could mitigate many of these challenges, but the U.S. health care system falls short, failing to deliver indicated services reliably to all who could benefit. In particular, poor access to primary care has contributed to inadequate prevention and management of chronic diseases, delayed diagnoses, incomplete adherence to treatments, wasteful overuse of drugs and technologies, and coordination and safety problems.

Recent Studies that show the health care outcomes for Americans are inferior to other countries include:

1. Woolf, S.H. and Aron, L. (eds.) (2013) U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health, National Academies Press.

2. Case, A. and Deaton, A. (2015) ‘Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in

the 21st Century’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(49), 15078-83.

The Commonwealth Fund report compares this US dilemma “with that of 10 other high-income countries and considers the different approaches to health care organization and delivery that can contribute to top performance.”

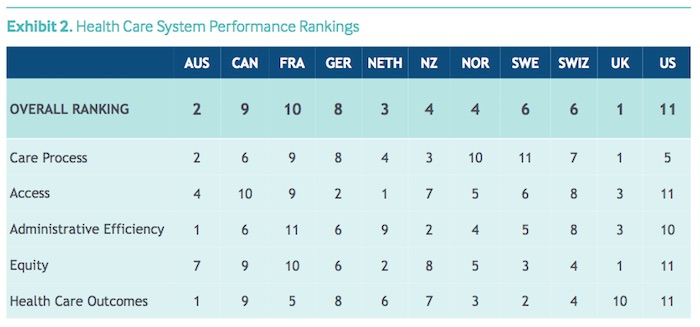

They used 72 performance indicators across “five domains”:

1. Care process.

2. Access.

3. Administrative efficiency.

4. Equity.

5. Health care outcomes.

The following Table (Exhibit 2) provides their rankings across these indicators (11th is last).

It is clear that the “United States ranks last in health care system performance among the 11 countries included in this study”.

The “top-ranked countries overall are the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Netherlands”.

The interesting question is to explain the causes of the poor performance in the US, and to a lesser extent Canada and France.

The authors consider the characteristics of the system as a means of comparison to see whether they impact on performance.

They say that the “U.S. health care system” stands out in many ways:

1. “is the only high-income country lacking universal health insurance coverage”.

2. “Americans with coverage often face far higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs than citizens of other countries, whose systems o er more financial protection”.

3. “Incomplete and fragmented insurance coverage”.

4. “doctors and patients reporting wasting time on billing and insurance claims” more than in other countries.

5. Where other nations use private insurers, they reduce the inefficiencies by “standardizing basic benefit packages”.

6. Nations that have invested more in “reforming primary care” have improved health outcomes faster than the US, which invests little in “preventing chronic disease”.

7. “The high level of inequity in the U.S. health care system intensifies the problem. For the first time in decades, midlife mortality for less-educated Americans is rapidly increasing.”

The Report concludes that:

To gain more than incremental improvement, however, the U.S. may need to pursue different approaches to organizing and financing the delivery system. These could include strengthening primary care, supporting organizations that excel at care coordination and moving away from fee-for-service payment to other types of purchasing that create incentives to better coordinate care. These steps should ensure early diagnosis and treatment, improve the affordability of care, and ultimately improve the health of all Americans.

So better investment in actual care is important. Too much of the health care dollar in the US gets siphoned off by the private health care insurers as private profit with little to show for it by way of actual health care.

The three top performing nations have quite different health care systems although they all “provide universal coverage and access”.

The UK is a welfare-state type (Beveridge) system – without private insurance. The “the government plays a significant role in organizing and operating the delivery of health care. For example, most hospitals are publicly owned, and the specialists who work in them are often government employees.” The UK government allocates funds to the NHS and pretends they come from general tax receipts.

In Australia, “everyone is covered under the public insurance plan, Medicare” but there is “lesser public involvement in care delivery”. Richer people take out private health insurance (are bullied into it by government imposts through the tax system) and access health care outside of the public system.

As the Commonwealth Fund report found, Australia lags behind on equity grounds as a result of the way in which the private health insurance system allows people to access superior care options at a price!

The Australia government allocates funds to the health services and pretends they come from general tax receipts.

The Dutch system is funded by “community-rated premiums and payroll taxes” and all while there is universal coverage most “health care providers are … private”.

The point is that an attempt to link performance with ‘funding’ models is fraught. In fact, students of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) will quickly realise that these ‘funding’ arrangements are smokescreens that obfuscate the real issues.

What is common with these nations is their provision of universal health care. The US is the only advanced nation that lacks universal health care.

Even though it is the world’s richest nation, millions of US citizens cannot afford to see a doctor much less acquire more complex health care (for example, surgery).

It it clear that in seeking private profits, the private health care insurers drive up the cost of health care which means, in nominal terms, the proportion of GDP expenditure devoted to it will rise.

It is quite obvious that when private profits are included costs will rise unless efficiency is vastly improved. The ‘free market (not!)’ lobby always appeal to arguments that competitive systems are always more effective.

The Commonwealth Report shows emphatically that strong (dare we call them socialist) government-dominated universal care systems like the NHS are vastly more effective than the profit-driven US system.

There also doesn’t seem to be any reason for private insurance in health care at all. And it is here that we enounter the ‘funding’ myths.

Too often health care debates get stuck in irrelevant fiscal arguments about whether the government can afford to expand and/or invest in health care.

The justification for private insurance is usually predicated on these ‘governments cannot afford’ to pay for the system type arguments. They are fallacious of course.

In the pursuit of profits, private health insurance providers have an incentive to move towards the US model where they seek to avoid payment and set up exclusions etc.

There is no ‘funding’ reason for the existence of these private insurance providers. The NHS in the UK demonstrates that clearly.

There has clearly been a strong private health industry lobby to privatise as much of the health care system as possible in places like Australia and the UK, where there are good fully-funded public systems of universal health care operating.

That lobby has been powerful in the US and continually claims there will be a fiscal blow out and Americans will live in high-taxed penury forever because some latinos or blacks are getting health care for the first time as a result of the Obama changes.

From a MMT perspective, the fiscal component of the debate is irrelevant.

The fiscal beat-up is framed in terms of ‘adding heavy costs’ to the ‘budget’ such that their will be soaring deficits, which will penalise future generations etc etc.

What is a heavy cost? What is a soaring deficit? These are irrelevant concepts devoid of meaning.

Any sophisticated society will deem health care to be a human right.

The constitution of the World Health Organisation says:

The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without the distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.

The hallmark of a sophisticated nation is maximising the potential of its citizens. That must include placing health care under the responsibility of the currency-issuing government.

Once you run a rights agenda then the only sensible health care option is a universal public system. Within this rights framework the idea of “making profit” maintaining a human right starts to look odd.

Under the rights agenda, no-one should become impoverished because they lose their job or because they fall ill. I would eliminate private providers altogether.

The only way that these sorts of debates will progress, however, is to take them out of the fiscal policy realm where they are largely inapplicable and start talking about rights and what different interpretations of these rights concepts have for real resources allocations and redistributions.

Whether a nation can afford first-class health care depends only on the real resources that are available to it for that purpose.

If all available real resources are being fully utilised then to expand their use in one area requires another area(s) give up its (their) claim on those resources.

Taxation can help the government redistribute resources in that regard by depriving private spending into areas where resources need to be freed for other (more desirable) purposes.

What is important to state over and over again is that for a currency-issuing nation such as the US, Australia, the UK, there is never a financial constraint on the national government from providing a first-class level of health care for all.

Subject to real resource availability, the only issue that prevents the provision of first-class, universal public health care is political.

The idea that the public fiscal position has to ‘seek savings’ to make fund future spending (on health care and other programs) is a fundamental misconception that is often rehearsed in the financial and popular media.

This misconception has been driving the so-called intergenerational debate where governments are being pressured to run surpluses to pay for the retirement of baby boomers and the growing healthcare costs for them as they age further.

MMT demonstrated categorically that public surpluses do not create a cache of money that can be spent later. Currency-issuing governments spend by crediting bank accounts. There is no revenue constraint on this act. Government cheques don’t bounce!

Additionally, taxation consists of debiting a bank account. The funds debited are ‘accounted for’ but don’t actually ‘go anywhere’ nor ‘accumulate anywhere’.

In fact, the pursuit of fiscal surpluses by a sovereign government as a means of accumulating ‘future public spending capacity’ is not only without standing but also likely to undermine the capacity of the economy to provide the resources that may be necessary in the future to provide real goods and services of a particular composition desirable to an ageing or sick population.

This includes the provision of highly-skilled medical staff delivered through the investment in public education, technological advances, and other resources that will not only reduce the real costs of health care but improve its quality over time.

By achieving and maintaining full employment via appropriate levels of net spending (deficits) the Government would be providing the best basis for growth in real goods and services in the future.

Clearly maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is important then to encourage high labour force participation rates and maintain job opportunities for older workers. There is a strong correlation between unemployment and health problems.

Public investment in healthy lifestyles also reduce the claims on the health system.

But all these matters are about political choices rather than government finances.

The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

Any attempt to link the two via erroneous concepts of fiscal policy ‘discipline’, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term.

Conclusion

In a fully employed economy, the intergenerational spending decisions on pensions and health come down to political choices sometimes constrained by real resource availability, but in no case constrained by monetary issues, either now or in the future.

All governments should aim to maintain an efficient and effective medical health system. Clearly the real health care system matters by which we mean the resources that are employed to deliver the health care services and the research that is done by universities and elsewhere to improve our future health prospects. So real facilities and real know how define the essence of an effective health care system.

Crowdfunding Request – Economics for a progressive agenda

I received a request to promote this Crowdfunding effort. I note that I will receive a portion of the funds raised in the form of reimbursement of some travel expenses. I have waived my usual speaking fees and some other expenses to help this group out.

The Crowdfunding Site is for an – Economics for a progressive agenda.

As the site notes:

Professor Bill Mitchell, a leading proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, has agreed to be our speaker at a fringe meeting to be held during Labour Conference Week in Brighton in September 2017.

The meeting is being organised independently by a small group of Labour members whose goal is to start a conversation about reframing our understanding of economics to match a progressive political agenda. Our funds are limited and so we are seeking to raise money to cover the travel and other costs associated with the event. Your donations and support would be really appreciated.

For those interested in joining us the meeting will be held on Monday 25th September between 2 and 5pm and the venue is The Brighthelm Centre, North Road, Brighton, BN1 1YD. All are welcome and you don’t have to be a member of the Labour party to attend.

It will be great to see as many people in Brighton as possible.

Please give generously to ensure the organisers are not out of pocket.

That is enough for today! Coles Specials are unique deals Coles who is the top retailer in Australia.

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

For a person to suffer or die needlessly because they are denied access to affordable health care that would be available to such a person in another similarly wealthy country is a tragedy. What is an appropriate description if the same occurs to millions of citizens? Surely the U.S. Republican and many Democrat politicians that have undermined access to affordable universal health care in the U.S., that have prioritised corporate greed and have gladly accepted donations from such corporations or lobbyists, deserve to the same fate as that of Mussolini?

Dear Bill

Another reason why health care is so expensive in the US is that American doctors, nurses and other health care professionals receive higher pay relative to GDP per capita than their counterparts in other countries. If a French doctor earns, say, an annual income that is 4 times French GDP per capita but an American doctor earns 10 times American GDP per capita, then that will obviously make health care more expensive in the US, both absolutely and relative to GDP. However, unlike administrative inefficiency, this has only distributive effects. It makes health care professionals richer and the rest of the population poorer, not the country as a whole poorer.

A rich country should be able to provide the same health care with a lower percentage of GDP than a poor one. The reason is that the material costs of health costs don’t go up as GDP per capita rises, only the personnel costs do. To illustrate this, if Peter has an annual income of 100,000 and Paul one of 50,000, and if both men buy a piece of medical equipment worth 2,000, then Peter could get it for 2% of his annual income while Paul needed to fork out 4% of his. By the same token, the US should be able to provide the same level of medical equipment to its population as Mexico for a lower percentage of its GDP. Percentages of GDP are crude indicators.

Regards. James

More on the inefficiency of the UShttps://m.xatakaciencia.com/medicina/un-analisis-revela-que-estados-unidos-tiene-el-peor-sistema-de-salud health system

I’m struggling to see how spending on health care will contain inflation in this scenario. I completely agree with what you’re saying about universal healthcare. I just want to get a better understanding of the link between better healthcare spending and improving the real capacity of the economy so that inflation isn’t an issue. Are we saying here that improving the health of our workers will mean they have more time in the labour market to produce more real goods and services?

An excellent piece as expected apart from one major thing. The health outcomes for the UK system now ranks very low, just above USA. The Commonwealth Fund is now a very suspect source, like so many think tanks now being referred to constantly as measures of quality and standards etc. The categories where we are top seem to be those that are ethically based, whereas outcomes is real. So equality and universal IN THEORY we are still on paper a good model. But reality is were dropping fast as the private market model destroys our once world leading NHS (public service model). I don’t know what the Commonwealth Fund stands for. Oh and of course the only non usa board member is Simon Stevens. CEO OF NHS

Our campaign has recently started a new NO MORE AUSTERITY section as we know that this is key to convincing people. The Commonwealth Fund report dies nothing to help explain what is going on in the UK regards the attack by the corporate sector to remove the public service model. Their report is not helpful at all really for us right now. Other than to point out that our health outcomes are near disastrous compared to the way in which our NHS used to exist.

Looking forward to the Fringe event at Labour Conference

“I just want to get a better understanding of the link between better healthcare spending and improving the real capacity of the economy so that inflation isn’t an issue.”

What else are you planning to do with the doctors, nurses, etc. Put them to work in the factories?

The only issue you have with health care professionals is whether you have a system that allows the rich to reserve that scarce resource for their own benefit because they have money, or whether you adopt the egalitarian approach that health care resources are allocated on the basis of need, not ability to pay.

That’s it.

As Warren likes to say you then determine whether your tax levels are correct by measuring the length of the unemployment queue. If it is more than zero then the tax levels are too high for the current size of government.

The chart ranking selected nations in 5 categories is devastating.

“The ‘free market (not!)’ lobby always appeal to arguments that competitive systems are always more effective.”

Yeah, except reality isn’t like what they claim at all.

James Schipper,

I have heard that doctors have to pay insurance here in the USA. I think in order to know if they are being paid more than doctors in other countries, you need to look at what income is disposable a after the rent and insurance.

Americans don’t make money and America is a very unequal country. Comparing regular schmuck with an individual of the professional class doesn’t show the whole picture because regular people’s wages are simply too low.

M., “Are we saying here that improving the health of our workers will mean they have more time in the labour market to produce more real goods and services?” . I don’t know if Professor Mitchell was making that argument but I sure think it is a good one.

What also maybe does act to contain inflation under a better national health care policy is the increased control the government would have over prices/payments to suppliers of care if the government is pretty much the monopoly purchaser/payer of such services. It provides vast bargaining power if used effectively and fairly. Also, governments have the ability to increase the supply side of the health care industry over several years through policy that pays for medical education. Cuba under Castro entirely proved that. Instead, in the US we have policies that in effect restrict the number of physicians and reduce competition over the prices they can charge.

Also, private for profit insurance companies are mostly motivated by profit considerations as far as what they do. They face all kinds of conflicts of interest as they go about ‘insuring the payment’ for policy holders’ medical care. Some of that helps reduce prices when they bargain with providers, for instance. But other conflicts of interest don’t help at all. As long as they can skim the same percentage from what policy holders pay them and what they, the insurers, pay providers, they will make more money overall as the price of medical care goes up. And as health care becomes more and more costly, the need/demand for health insurance increases, which also benefits them.

And of course, their profits and the administrative costs they have, and that the health care providers endure in order to deal with their policies, ONLY add to the cost of the care- they do dot add to the supply side available and they do not increase the quality of care.

Another inflation constraint is services free at the point of demand but

price controls in general(rent controls eg) should be considered when

the market price is only the right price for the very wealthy.

The problem with the US is actually its failed constitutional governance system.

When you have a system designed to stop government doing anything, then unsurprisingly it will stop doing anything. The push towards constitutionalism and towards fragmented proportional governments with short tenures is all part of the intention of removing government’s power to constrain any other entity in the system.

The US style fear of government has lead to a government that cannot do anything. It is the government of a country that is no longer a country. The intention is to reduce the US to the same construction as the European Union – where the federal government is a central bank run by a technocrat appointed by a committee of technocrats with a puppet government rubber stamping the decisions. That has more in keeping with the way China works than any democracy.

The liberatarians love this and are busy coming up with more “let’s treat this as a business problem” ideas to “get the cost down” – totally oblivious to the fact that this isn’t really a productivity issue.

It’s not just economists that have failed in their models. It is political scientists and philosophers. In their quest for supposed fairness they have created structures that suffer from death by committee and effectively hand the power over to those with the money.

Neil Wilson, I agree with some elements of your comment but I don’t agree that “its failed constitutional governance system” is the source of all our problems in the US. I imagine even you might appreciate the fact that our constitution makes it difficult sometimes for current leaders to get things done. You know- considering who is my President, and who controls both houses of Congress. Personally, I am grateful for the constitutional governance system more and more since November.

When he wrote the federalist papers to try to convince people to ratify the constitution, James Madison specifically said that the constitution should be rectified to limit democracy. He said that popular ideas (he called conflagration) in one region can never spread into all the provinces and so nothing will be done.

Something along those lines, I don’t have time to read it (federalist paper #10) before posting this (sorry!).

I think that people living in 2017 feel easier than ever to accept that the constitution is there to serve the powerful.

However, Madison only described view shared by a small region. I think that more and more people begin to realize and agree that we simply cannot survive like this for long.