Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – July 22-23, 2017 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Irrespective of what the government does, the private domestic sector can still save overall, as long as the external sector delivers a surplus.

The answer is False.

This is a question about the relative magnitude of the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance. The balances taken together always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

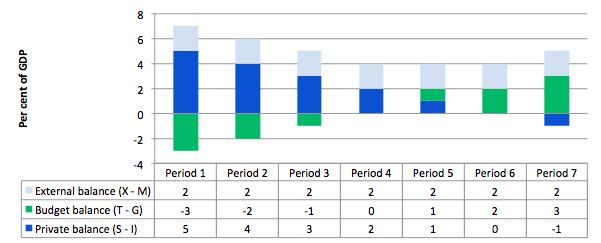

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. In each period I just held the fiscal balance at a constant surplus (2 per cent of GDP) (green bars). This is is artificial because as economic activity changes the automatic stabilisers would lead to endogenous changes in the fiscal balance. But we will just assume there is no change for simplicity. It doesn’t violate the logic.

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive – that is net addition to spending which would increase output and national income.

The external surplus also means that foreigners are decreasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus means the government is spending less than it is taking out of the economy via taxations which puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow. So the question is what are the relative magnitudes of the external add and the fiscal position subtract from income?

The following graph shows the range of options for a given external surplus (of 2 per cent of GDP).

In Periods 1 to 5, the private sector is saving because the public sector does not negate the overall contribution of the external sector to demand and hence growth. Clearly, the larger is the fiscal deficit the greater is the capacity of the private sector to save overall because the growth in income would be stronger.

In Periods 4 and 5, the fiscal position moves from deficit to balance then surplus, yet the private sector can still net save. That is because the fiscal drag coming from the fiscal position in Period 4 is zero and in Period 5 less than the aggregate demand add derived from the external sector.

In Periods 6 and 7, the private sector stops net saving because the fiscal drag coming from the fiscal surplus offsets (Period 6) and then overwhelms (Period 7) the aggregate demand add from the external sector.

The general rule when the economy runs an external surplus is that the private domestic sector will be able to net save if the fiscal surplus is less than the external surplus.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

Central bank interest payments to the private banks on reserves reduces the private banks’ incentive to advance credit to the private sector.

The answer is False.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provided enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system would grind to a halt and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and the banks’ own desires.

But banks do not lend reserves. They are used to facilitate the so-called payments system so that all transactions that are drawn on the various banks (cheques etc) clear at the end of each day. Clearly banks prefer to earn a return on reserves that it deems are in excess of its clearing house (payments system) requirements. Rare deals, quality products from ALDI catalogue will be in your shopping list this week.

But in the absence of such a return being paid by the central bank the only consequence would be that the banks (overall) would have zero interest balances.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

Question 3:

Rising government deficits indicate that its fiscal stance is becoming more expansionary.

The answer is False.

Intuitively, we might think that if the deficit rises the government must be pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy. But intuition is not always a good guide and doesn’t replace understanding.

The question is exploring the issue of decomposing the observed fiscal balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the fiscal process.

The fiscal balance is the difference between total government revenue and total government outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the fiscal position is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the fiscal balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the fiscal position is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the fiscal position is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the fiscal position back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Fiscal Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Fiscal Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the fiscal position in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal position goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Fiscal Balance was a hypothetical construct of the fiscal balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying fiscal parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment fiscal position would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the fiscal position was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the fiscal position was contractionary and vice versa if the fiscal position was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Crowdfunding Request – Economics for a progressive agenda

I received a request to promote this Crowdfunding effort. I note that I will receive a portion of the funds raised in the form of reimbursement of some travel expenses. I have waived my usual speaking fees and some other expenses to help this group out.

The Crowdfunding Site is for an – Economics for a progressive agenda.

As the site notes:

Professor Bill Mitchell, a leading proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, has agreed to be our speaker at a fringe meeting to be held during Labour Conference Week in Brighton in September 2017.

The meeting is being organised independently by a small group of Labour members whose goal is to start a conversation about reframing our understanding of economics to match a progressive political agenda. Our funds are limited and so we are seeking to raise money to cover the travel and other costs associated with the event. Your donations and support would be really appreciated.

For those interested in joining us the meeting will be held on Monday 25th September between 2 and 5pm and the venue is The Brighthelm Centre, North Road, Brighton, BN1 1YD. All are welcome and you don’t have to be a member of the Labour party to attend.

It will be great to see as many people in Brighton as possible.

Please give generously to ensure the organisers are not out of pocket.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments