The British press are reporting that the Government there is planning further spending cuts of…

Unemployment is miserable and doesn’t spawn an upsurge in personal creativity

Here is a summary of another interesting study I read last week (published March 30, 2017) – Happiness at Work – from academic researchers Jan‐Emmanuel De Neve and George Ward. It explores the relationship between happiness and labour force status, including whether an individual is employed or not and the types of jobs they are doing. The results reinforce a long literature, which emphatically concludes that people are devastated when they lose their jobs and do not adapt to unemployment as its duration increases. The unemployed are miserable and remain so even as they become entrenched in long-term unemployment. Further, they do not seem to sense (or exploit) a freedom to release some inner sense of creativity and purpose. The overwhelming proportion continually seek work – and relate their social status and life happiness to gaining a job, rather than living without a job on income support. The overwhelming conclusion is that “work makes up such an important part of our lives” and that result is robust across different countries and cultures. Being employed leads to much higher evaluations of the quality of life relative to being unemployed. And, nothing much has changed in this regard over the last 80 or so years. These results were well-known in the 1930s, for example. They have a strong bearing on the debate between income guarantees versus employment guarantees. The UBI proponents have produced no robust literature to refute these long-held findings.

While the ‘Happiness Study’ notes that “the relationship between happiness and employment is a complex and dynamic interaction that runs in both directions” the authors are unequivocal:

The overwhelming importance of having a job for happiness is evident throughout the analysis, and holds across all of the world’s regions. When considering the world’s population as a whole, people with a job evaluate the quality of their lives much more favorably than those who are unemployed. The importance of having a job extends far beyond the salary attached to it, with non-pecuniary aspects of employment such as social status, social relations, daily structure, and goals all exerting a strong influence on people’s happiness.

And, the inverse:

The importance of employment for people’s subjective wellbeing shines a spotlight on the misery and unhappiness associated with being unemployed.

There is a burgeoning literature on ‘happiness’, which the authors aim to contribute to.

They define happiness as “subjective well-being”, which is “measured along multiple dimensions”:

… life evaluation (by way of the Cantril “ladder of life”), positive and negative affect to measure respondents’ experienced positive and negative wellbeing, as well as the more domain-specific items of job satisfaction and employee engagement. We find that these diverse measures of subjective wellbeing correlate strongly with each other …

Cantril’s ‘Ladder of Life Scale’ (or “Cantril Ladder”) is used by polling organisations to assess well-being. It was developed by social researcher Hadley Cantril (1965) and documented in his book The pattern of human concerns.

You can learn more about the use of the ‘Cantril Ladder’ HERE.

As we read, the “Cantril Self-Anchoring Scale … consists of the following”:

- Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top.

- The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you.

- On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time? (ladder-present)

- On which step do you think you will stand about five years from now? (ladder-future)

[Reference: Cantril, H. (1965) The pattern of human concerns, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press.]

Christian Bjørnskov’s 2010 article – How Comparable are the Gallup World Poll Life Satisfaction Data? – also describes how it works.

[Reference: Bjørnskov, C. (2010) ‘How Comparable are the Gallup World Poll Life Satisfaction Data?’, Journal of Happiness Studies, 11 (1), 41-60.]

The Cantril scale is usually reported as values between 0 and 10.

The authors in the happiness study use poll data from 150 nations which they say “is representative of 98% of the world’s population”. This survey data is available on a mostly annual basis since 2006.

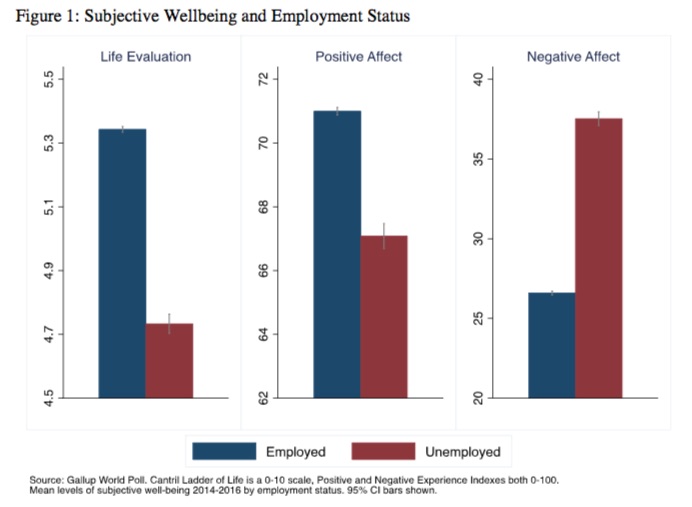

The following graph (Figure 1 from the Study) shows “the self-reported wellbeing of individuals around the world according to whether or not they are employed.”

The “bars measure the subjective wellbeing of individuals of working age” by employment status .

The results show the differences between having a job and being unemployed are “very large indeed” on the three well-being measures (life evaluation, positive and negative affective states).

People employed “evaluate the quality of their lives around 0.6 points higher on average as compared to the unemployed on a scale from 0 to 10.”

The authors also conduct more sophisticated (and searching) statistical analysis (multivariate regression) which control for a range of characteristics (gender, age, education, marital status, composition of household) as well as to “account for the many political, economic, and cultural differences between countries as well as year-to-year variation”.

The conclusion they reach is simple:

… the unemployed evaluate the overall state of their lives less highly on the Cantril ladder and experience more negative emotions in their day-to-day lives as well as fewer positive ones. These are among the most widely accepted and replicated findings in the science of happiness … Here, income is being held constant along with a number of other relevant covariates, showing that these unemployment effects go well beyond the income loss associated with losing one’s job.

These results are not surprising.

The earliest study of this sort of outcome was from the famous study published by Philip Eisenberg and Paul Lazersfeld in 1938.

[Reference: Eisenberg, P. and Lazarsfeld, P. (1938) ‘The psychological effects of unemployment’, Psychological Bulletin, 35(6), 358-390.]

They explore four dimensions of unemployment:

I. The Effects of Unemployment on Personality.

II. Socio-Political Attitudes Affected by Unemployment.

III. Differing Attitudes Produced by Unemployment and Related Factors.

IV. The Effects of Unemployment on Children and Youth.

On the first dimension, they conclude that:

1. “unemployment tends to make people more emotionally unstable than they were previous to unemployment”.

2. The unemployed experience feelings of “personal threat”; “fear”; “sense of proportion is shattered”; loss of “common sense of values”; “prestige … lost … in … own eyes … and as he imagines, in the eyes of his fellow men”; “feelings of inferiority”; loss of “self-confidence” and a general loss of “morale”.

Devastation, in other words.

They were not surprised because they note that:

… in the light of the structure of our society where the job one holds is the prime indicator of … status and prestige.

This is a crucial point that UBI advocates often ignore. There is a deeply entrenched cultural bias towards associating our work status with our general status and prestige and feelings of these standings.

That hasn’t changed since Eisenberg and Lazersfeld wrote up the findings of their study in 1938.

It might change over time but that will take a long process of re-education and cultural shift. Trying to dump a set of new cultural values that only a small minority might currently hold to onto a society that clearly still values work is only going to create major social tensions.

Eisenberg and Lazarsfeld also considered an earlier 1937 study by Cantril who explored whether “the unemployed tend to evolve more imaginative schemes than the employed”.

[Reference: Cantril, H. (1934) ‘The Social Psychology of Everyday Life’, Psychological Bulletin, 31, 297-330.]

The proposition was (is) that once unemployed, do people then explore new options that were not possible while working, which deliver them with the satisfaction that they lose when they become jobless.

The specific question asked in the research was: “Have there been any changes of interests and habits among the unemployed?”

Related studies found that the “unemployed become so apathetic that they rarely read anything”. Other activities, such as attending movies etc were seen as being motivated by the need to “kill time” – “a minimal indication of the increased desire for such attendance”.

On the third dimension, Eisenberg and Lazersfeld examine the questions – “Are there unemployed who don’t want to work? Is the relief situation likely to increase this number?”, which are still a central issue today – the bludger being subsidised by income support.

They concluded that:

… the number is few. In spite of hopeless attempts the unemployed continually look for work, often going back again and again to their last place of work. Other writers reiterate this point.

So for decades, researchers in this area, as opposed to bloggers who wax lyrical on their own opinions, have known that the importance of work in our lives goes well beyond the income we earn.

The non-pecuniary effects of not having a job are significant in terms of lost status, social alienation, abandonment of daily structure etc, and that has not changed much over history.

The happiness paper did explore “how short-lived is the misery associated with being out of work” in the current cultural settings.

The proposition examined was that:

If the pain is only fleeting and people quickly get used to being unemployed, then we might see joblessness as less of a key public policy priority in terms of happiness.

They conclude that:

… a number of studies have demonstrated that people do not adapt much, if at all, to being unemployed … there is a large initial shock to becoming unemployed, and then as people stay unemployed over time their levels of life satisfaction remain low …. several studies have shown that even once a person becomes re-employed, the prior experience of unemployment leaves a mark on his or her happiness.

So there is no sudden or even medium-term realisation that being jobless endows the individual with a new sense of freedom to become their creative selves, freed from the yoke of work. To bloom into musicians, artists, or whatever.

The reality is that there is an on-going malaise – a deeply entrenched sense of failure is overwhelming, which stifles happiness and creativity, even after the individual is able to return to work.

This negativity, borne heavily by the individual, however, also impacts on society in general.

The paper recognises that:

A further canonical finding in the literature on unemployment and subjective wellbeing is that there are so-called “spillover” effects.

High levels of unemployment “increase fear and heighten the sense of job insecurity”. Who will lose their job next type questions?

The researchers found in their data that the higher is the unemployment rate the greater the anxiety among those who remain employed.

Conclusion

The overwhelming conclusion is that “work makes up such an important part of our lives” and that result is robust across different countries and cultures.

Being employed leads to much higher evaluations of the quality of life relative to being unemployed.

The unemployed are miserable and remain so even as they become entrenched in long-term unemployment. They do not seem to sense (or exploit) a freedom to release some inner sense of creativity and purpose.

The overwhelming proportion continually seek work – and relate their social status and life happiness to gaining a job, rather than living without a job on income support.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) allows us to understand that it is the government that chooses the unemployment rate – it is a political choice.

For currency-issuing governments it means their deficits are too low relative to the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector.

For Eurozone-type nations, it means that in surrendering their currencies and adopting a foreign currency, they are unable to guarantee sufficient work in the face of negative shifts in non-government spending. Again, a political choice.

The Job Guarantee can be used as a vehicle to not only ensure their are sufficient jobs available at all times but also to start a process of wiping out the worst jobs in the non-government sector.

That can be done by using the JG wage to ensure low-paid private employers have to restructure their workplaces and pay higher wages and achieve higher productivity in order to attract labour from the Job Guarantee pool.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book with Joan Muysken analysing the Future of Work. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

2. Employment as a human right.

3. The rise of the “private government.

4. The evolution of full employment legislation in the US.

5. Automation and full employment – back to the 1960s.

6. Countering the march of the robots narrative.

7. Unemployment is miserable and does not spawn an upsurge in personal creativity.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due in 2018. The book will likely be published by Edward Elgar (UK).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill

I have two points to ponder.

Point 1.

I have at various stages in my life been unemployed and to some extent, I am still underemployed.

I’m not sure what was worse, the feeling of alienation, desperation or having my dignity buffeted by useless people at the jobcentre and a useless system. The system, by the way, had a scheme where the jobcentre would fund up to two interviews per job.

Little did I know that this only applied to jobs where the salary was lower than £25,000. If the salary for the job was higher, then no funding was available. The logic according to the jobcentre was that if you were applying for jobs with large salaries then you must have come from another job with a large salary and therefore would have saved money to pay for travel.

The jobcentre would then call the interviewer to confirm that I had, in fact, got an interview. They were not exactly discrete when they phoned. So, the end result was, the candidate was on the backfoot straight away. Not to mention that I had to apply for jobs below £25,000 or I wouldn’t be able to get to the interview. There’s more to say about this but I want to ponder point 2.

Point 2.

I agree that work and meaningful work is vital for mental well being but I think we need to be careful with what exactly that means. The devil is in the detail.

I started work in the 1970’s and remember working as a trainee telecom engineer for the Post Office as it was then. The big thing at the time was demarcation where jobs were protected.

As an example, I remember that a lightbulb had blown and needed replacing. It took two people to do the replacement, an electrician and a chippy. The reason light was in a wooden surround and needed a person whose job was to work with wood.

So, yes, let’s ensure everyone can work and take some meaning from their work but let’s give some thought to how work is defined and managed.

By the way, I was lucky when unemployed as the council had a scheme which gave unemployed people access to sports facilities at a large discount. I managed to stave off depression by playing Tennis. It got me mixing with people and helped me keep a reasonable equilibrium.

These facilities have all now been outsourced to the private sector so doubt they are available at discounts anymore.

Very sad.

Bill, You criticise UBI on the grounds that it increases unemployment. That, by definition, is not true. Unemployment consists of wanting work and not being able to find it. UBI in contrast, offers a life of leisure to those who want it, and there are plenty of people who do want a life of leisure, if only at a very modest standard of living, far as I can see.

Over the last few decades, there have been three people living within 100 meters of me who have, for decades on end, gone to extreme lengths to claim invalidity benefit for fraudulent reasons. I.e. they are professional social security fraudsters. I know them well, and can testify that they very much enjoy their leisure. They are all nice sociable people, which in a sense figures: that is, they much prefer socializing to working.

‘Related studies found that the “unemployed become so apathetic that they rarely read anything”. Other activities, such as attending movies etc were seen as being motivated by the need to “kill time” – “a minimal indication of the increased desire for such attendance”.

I think some of this could be alleviated by the availability of educational facilities, adult education, which was torn apart in the 80’s. I can remember, back in the 80’s, adult education facilities offered a forum for people to meet, take classes and socialise. This has largely gone in the UK.

As someone who is not working due to health problems I often tell people that the challenge to shape your own day is a lot greater than someone in work -but unfortunately, the perception is that that those not working are ‘leading the life of Riley’ still persists in the UK after years of the Tories plugging the ‘skiver/striver’ meme.

Ralph,

‘for decades on end, gone to extreme lengths to claim invalidity benefit for fraudulent reasons. I.e. they are professional social security fraudsters. ‘

how do you know they are ‘fraudsters’ -have you carried out your own medical assessment? In any case, even if they were ‘fraudsters’ ( DWP estimates ‘fraud’ at 0.7%) this would be in the context of a society that is built on ‘fraud’ and rentier activity.

It is true that some people prefer not to work but there are very few of them, maybe 100,000 or so. The JG wording always mentions ‘able and willing’ so the choice will be there to subsist on a low income.

The relationship between work and social value has become very fuzzy-so having a job is not automatically indicative of doing something that enhances well-being. So one could argue that many activities are better not done. In that respect a choice to not work could be defensible. Especially so in a rentier society where working can create treadmill debt slavery.

From a biological perspective “resource holding potential” is vital for most male animals to achieve reproductive success and fitness to bear and rear offspring is important for female reproductive success. In human society our market systems under fiscal austerity, place severe and largely artificial constraints on the ability of many “able and willing” males and females (of reproductive age) to find a way to acquire the resources needed to signal fitness as a mate. This has to have profound psychological and hence social effects; well beyond simple happiness.

That we have a system in place were the “happiness” of the 1%, who determine the “political will” is proportional to the degree of control they can exert over the way everyone else lives, is deeply disturbing and a signal that we are in big trouble as a species.

Income support for the unemployed is not like a UBI. People recieving a UBI can work and still recieve the UBI. They can start up an enterprise of their own to supplement the UBI. Unemployment creates apathy and misery precisely because the unemployed don’t have the resources to start up on their own and if they do, then anything they earn will be offset by reductions in income support (unless and untill their new enterprise were to do really well). A UBI is more akin to the capital income that wealthy people earn. Many wealthy people do manage to do valuable and rewarding work. In many cases their capital income provides them with the economic freedom to make the most productive use of their talents. A UBI would simply be distributing that to everyone. Afterall, about 40% of income accrues to capital rather than to labour and a UBI can simply be thought of as a way to ensure that such capital income gets universally distributed.

Great article.

When I first started with MMT, L. Randall Wray mentioned problems that spring out when people become unemployed, but I admit I didn’t read much more into that.

Didn’t know what the Cantril scale was, but now I do.

I realise that work is a key part of happiness. As a woman and mother I have to say though that combining full-time work with domestic responsibilities is “too much work”. I hope that the job guarantee can be designed so that it recognises the work women do in the home and community and offers job opportunities that allow women to work flexibly and utilise their skills to the benefit of the community (those skills that the private sector only wants if it’s full-time 9-5). So many women are stifled as workers by a lack of work that fits in with the domestic load and childcare costs that make working hardly worth it. Wages for housewives? MMT and feminism – how can they work together?

Hi Bill,

What does the literature say on how damaging a bad job is, as compared to being unemployed? Is it possible for a job to be so bad, that one is better off being unemployed?

“A UBI is more akin to the capital income that wealthy people earn.”

Correct. Also known as ‘stealing from the actual workers who produce stuff’.

The rich are resented for it because they haven’t earned it. And that resentment would transfer, correctly, to anybody receiving income that they haven’t earned.

The Job Guarantee sorts the Workers from the Shirkers, and the only people who object to the JG are those who really want to be shirkers. Generally middle class. Generally metro-liberal. Generally shouting about how good the UBI would be for the poor (kof, kof).

“I hope that the job guarantee can be designed so that it recognises the work women do in the home and community”

When a child is born, or somebody becomes disabled, a job of work is created. Somebody has to do it. And since it is work, then surely it should be paid at the living wage?

We can debate how that work is to be done – individual care or collective care – but it still has to be done.

Simon, You ask how do I know that relevant individuals are fraudsters. Here’s an illustration. I dropped in to have a cup of tea and chat with one bloke twice a week who claimed (when in front of social security investigators) that he had arthritis in his fingers. But over the 20 years I knew him, he managed to do the house work, and gardening, and played the accordian, and did his shopping all without ever once complaining about arthritis in his fingers.

Re your point that “a choice to not work could be defensible” I fully agree. That’s why I support UBI. Indeed, the reality is that UBI is already with us, in that (at least in the UK) anyone who is determined to, can spend most of their lives living on benefits.

Are there studies which examine the hours worked and corresponding levels of happiness?

Bill I think you are ignoring the nuance of happiness science,

Of the primary categories listed in the UN WHR that contribute to happiness, I don’t believe “work” is an explicit category, from memory there is social connections, health, community trust, faith in leaders .etc, but not “work”.

How do you marry the disparate facts that work is correlated with well-being and yet a near majority of people self report that they hate their jobs. Many commentators have suggested one solution which seems satisfactory – people form strong social connections at work (which is an explicit WHR category) which often dissolve when employment is terminated.

I have been unemployed for a 8 month period and I was much happier than I was at work, for the first 4 months, what reduced my happiness was when I had to start looking for work again. My dwindling finances and legion rejections from employers start to stress you out and chip away your self confidence.

So I would assert that the unhappiness correlated with unemployment is due to: loss of some/all social networks, insufficient finance, social norms which denigrate the unemployed, constant rejections from employers and YES… loss of a (singular) goal/sense of purpose.

So unemployment for a person who maintains a social network, has a goal/purpose (a hobby, project), who has sufficient finance so as to not constantly count their gold coins and is not called a ‘bludger’ ….will be a very happy unemployed person indeed. I was

“The unemployed are miserable and remain so even as they become entrenched in long-term unemployment. They do not seem to sense (or exploit) a freedom to release some inner sense of creativity and purpose”

Funny, because I’ve been unemployed for the last couple of months and I don’t recognise this at all. Being free from ‘real’ work has meant I now have time to focus on what I really want to do. A UBI would be great for me because it would give me a stipend to cover the essentials and allow me to concentrate on my desired career without having to waste my time in a ‘real’ job and put up with idiotic, incompetent managers and people blinded by non-ambition and groupthink who don’t really have any interest in me outside of what I do in said job. Unless a job guarantee means I can work from home, for me it would just mean having to start driving 20 miles to the nearest town again and work under somebody else’s direction again instead of on what I want to do. No thanks, I’ve already wasted enough years doing that.

You may object to being treated as a consumption unit, but I don’t. That’s how the government sees all of its citizens anyway – problem factories who can be made to go away if they throw enough cash at them. I doubt an MMT government would have a different attitude. And some of us don’t have much in the way of a social life or friends nearby and that’s fine for us. It’s how we’re wired.

It’s time we stop trying to find ways to keep people working 40 hours a week just because that’s the way it’s always been when we could clearly start reducing that with a bit of effort. If you really believe work makes you happy or free (I’m pretty sure that was a slogan at one point) then fine, but I would happily wager that they would also be just as happy working 20 hours a week if that was the norm for everyone. The employed are only happier because they know they can probably pay their bills that month by staying. Take that factor out and 95% of them would choose not to be there.

To all commentators

Please note that in relation to comments proposing a UBI that I will delete them unless you engage with the issues that MMT authors have written about extensively.

Merely saying that you think a UBI is great and then provide further references to authors who similarly do not understand the macroeconomic implications of the introduction of a UBI will not justify publication on this blog.

We have documented for many years – well before the UBI idea became the darling of the ‘Left’ – why a UBI will fail in macroeconomic terms. Those issues are almost always avoided by proponents of the UBI who choose, instead, to talk about freedom and individual creativity and stuff like that.

The comments section of my blog will not become a forum for these sorts of pro-UBI advocacy. There are many other places you can go to make those points.

Engage with the macroeconomics and we can have a debate. For a starting point go to – Job Guarantee – and work your way through all the entries.

Sorry to disappoint.

best wishes

bill