It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

British Tories reject the ‘free market’ neoliberal myth

The conservatives in the British Labour Party are obviously worried. The UK Guardian article (December 2, 2017) – Labour faces subversion by Momentum and far left, says Roy Hattersley – reports the claim by former Deputy leader, Roy Hattersley that British Labour is “facing the biggest crisis in its history” because left-wingers are engaged “in a systematic takeover of the party”. Gosh. Sounds shocking. A traditionally left-wing political party slowly wresting it back to mission after being hijacked by the right-wing, neoliberal Blairites. That sounds like Armageddon. The Blairites tried to kill off Jeremy Corbyn several times as they continued to undermine him in the public eye and bleated about how he was going to destroy the Labour Party. They then fell silent when he nearly delivered the Party government in the recent national election and saved many of their jobs. Now, with a by-election in Watford, the conservatives are back to it although it has to be said that Hattersley cannot be called a Blairite. He represents the pre-Blairite right-wingers who backed Dennis Healey as he imposed Monetarist ideology on the Party in the mid-1970s. And this article came out soon after the Tory government announced a major ‘socialist’-style industrial plan. In its press release (November 27, 2017) – Government unveils Industrial Strategy to boost productivity and earning power of people across the UK we learn that the Tories are finally understanding that it can actually improve the fortunes of British workers by abandoning the failed neoliberal, ‘free market’ narrative and recognising, instead, the central role to be played by the nation state in advancing well-being and economic fortune.

Hattersley shifted to the right in the 1970s and voted with the Tories to support Britain’s entry into the European Union. He was part of the James Callaghan Monetarist move in the mid-1970s and was vehemently opposed to the Bennites (Socialists) in the Parliamentary Party.

He used to rail against the Bennites accusing them of destroying Labour.

For example, in his 2017 autobiography – Who Goes Home?: Scenes from a Political Life – Hattersley wrote about his role in 1981 in helping Denis Healey see off a challenge from Tony Benn for Deputy Leader:

… I played my part in making the decision which turned the tide. If Denis had lost, thousands of moderates would have deserted Labour and the Bennite alliance – Trotskyites, one subject campaigners, Marxists who had never read Marx, Maoists, pathological dissidents, Utopians and, most dangerous of all, sentimentalists – would have turned the Party into an unhealthy hybrid of pressure group and protest movement. As it was, they merely played a major part in keeping the Conservatives in power for almost twenty years. It is difficult to say who helped Margaret Thatcher and the Tories the most – the Social Democrats who claimed that Labour was lost to extremism or the Bennite left who tried to prove them right.

Healey won in a two-round contest (given there were three initial candidates) by 50.4 per cent to 49.6 per cent.

Like many of these Labour Party types, allegedly serving to advance the interests of workers and who operated under a political manifesto to scrap the House of Lords, he accepted a peerage from none other than Tony Blair in 1997.

He also thought Tony Blair’s illegal move to invade Iraq was an example of Blair demonstrating “strong leadership” (Source)

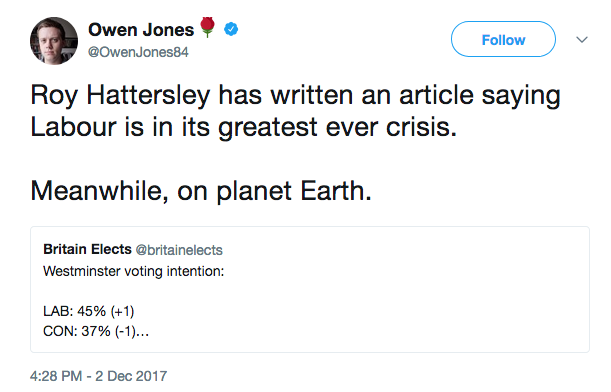

I thought Owen Jones tweet was an adequate summary of Hattersley’s intervention.

The UK Guardian seems to be running a concerted anti-Corbyn campaign at present – well it has renewed the attacks, which are getting increasingly personal.

Not content to publish Keegan’s on-going rants about Brexit, they published an article (December 9, 2017) by Nick Cohen – What would it take for Labour’s moderates to revolt? – which for pure vitriol ranks among the best.

Cohen, by the way, was a staunch supporter of the illegal invasion of Iraq and wants the West to launch a military invasion of Syria. He is that sort of guy.

I recall a column in the New Statesman (June 7, 2010) where Cohen was described as providing “weird and wonderful claims” about the Israel-Palestine conflict (Cohen being firmly pro-Israeli).

The journalist wrote:

His columns become more ridiculous (not to mention right-wing) by the week. On 8 May, for example, Cohen urged the Liberal Democrats to form a coalition with the Conservatives (and not Labour): “There is no point in being in politics if they do not.” The following week, however, on 16 May, he accused the Liberal Democrats of having “toffed up” the Cameron-led coalition and “sundered their links with the social democratic tradition”, and described Vince Cable as a “good social democrat who threw in his lot with the Tories . . . a man with a mortal sin on his conscience.”

Bizarre. Does the Observer not provide this man with an editor? A sub? A reviewer of copy?

It seems that the UK Guardian also doesn’t provide Cohen with any feedback.

His attack on Corbyn and John McDonnell is blitheringly ridiculous but part of a massive right-wing attack that is accelerating again. They, largely went quiet after the election because, after all, what could they say?

Now the likes of Cohen are suggesting the Labour supporters “don’t know who they are following” or “may be ignorant” and that Corbyn is a “dim man”.

Cohen qualifications to speak about matters macroeconomic are encapsulated in this statement:

The Labour leadership’s inability to understand that its government would be unable to afford its programmes if Britain left the single market means that its social reforms could unravel.

Blitheringly ridiculous – blithering idiot!

The British government will always be able to ‘afford’ its programs as long as there are the commensurate availability of real resources available to implement them.

The only constraint that a newly-elected Labour government would have in implementing its infrastructure plans would be if there was available capital and labour shortages.

In that case, should it wish to persist with these plans and there was already full employment of productive resources, then the government would have to divert resources from other uses to its intended uses.

That diversion would have nothing to do with Britain’s EU membership or its participation in the single market.

This mistake is also made by the UK Guardian economist Larry Elliot in his latest article (December 10, 2017) – Attacks on McDonnell a sign Tories know stance on borrowing is defunct.

Larry Elliot comments on recent fumbles by John McDonnell in interviews, which he assesses reflects a Shadow Chancellor who was “overconfident and underprepared”.

It seemed odd to me that John McDonnell was not, seemingly, on top of basic details about “Labour’s spending plans” and the interest income that British sovereign debt holders receive each year.

But Larry Elliot goes further and writes:

Extra borrowing certainly means an increase in the national debt and higher debt interest payments in the short term, but that is not the real issue.

Imagine the chief executive of a FTSE 100 company going on TV to announce that the company was planning to go to the City to finance a new plant. The interview would not centre on what the investment meant for the company’s debt interest payments. The chief executive would be asked about what it meant for jobs, earnings and profits.

In the event that the chief executive was asked about the cost of the investment, they would give the same answer as McDonnell did, that at current rates of interest the investment would more than pay for itself, because otherwise we would not be doing it. Our debt interest payments will depend on what happens to interest rates and inflation, but our best judgment is that the investment will wash itself.

Instead of obsessing about the red herring of debt interest payments, more attention should be paid to the things that do matter. Labour is planning to borrow to invest, not to cover day-to-day government spending, and that makes sense if the return on the investment is higher than the cost of financing the extra debt.

Governments do not go bust, which means that they can borrow more cheaply than companies.

Which perpetuates the neoliberal myth that currency-issuing governments have to borrow before they can spend. John McDonnell would be better serving the progressive movement if he made that point over and over again.

Instead of trying to fudge how much public debt will rise in the UK it would be more instructive to present the view that a shift to Overt Monetary Financing (OMF) should occur.

I have written about OMF in these blogs (among others):

1. OMF – paranoia for many but a solution for all.

2. Helicopter money is a fiscal operation and is not inherently inflationary.

3. Overt Monetary Financing would flush out the ideological disdain for fiscal policy.

4. The Bank of Japan needs to introduce Overt Monetary Financing next.

5. Overt Monetary Financing – again.

6. There is no need to issue public debt.

And Larry Elliot makes the classic mistake in invoking a version of the ‘household budget analogy’. In this variation, he uses the ‘if it is okay for Corporations to invest to create returns then it is okay for Governments to do the same’ myth.

The Left often fall for this furphy and then get bogged down trying to outline the returns from the investment in public infrastructure.

The tendency, then, is to agree to all sorts of ridiculous user pays schemes (for example, toll roads, increased public transport fares etc) to make the ‘returns’ more concrete. Everyone understands a $ value (or in context a £ value)!

In Australia at present, we have a massive clusterf*xk emerging in the form of the National Broadband Network because the Federal Government is insisting the infrastructure has to be fully paid for via user charges. The problem is that the charges are so high that few people want to pay the top price so degraded service is the result. Ridiculous.

Please read my blog – The neo-liberal infestation – Australia’s broadband fiasco gets worse – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that a corporation is financially constrained (like a household) whereas the British government is not if it doesn’t want to be.

The experience of a corporation (or a household) provides no guidance to how a currency-issuing government should behave.

That is not to say that ;oliticians should demonstrate that their spending is delivering social returns and the spending is not wasteful or unduly lining the pockets of developers, construction companies etc.

But they should also make the break with any notion that this spending is dependent on the preferences of the bond markets.

All of which allows us to link Roy Hattersley’s hatred of Bennites and the national infrastructure debate.

I considered Tony Benn’s role in advancing an alternative vision for the Labour Party in the mid-1970s, in my series of blogs under the category – Demise of the Left. His plans were rejected by Harold Wilson and Denis Healey, who preferred to advance the myth that Britain had run out of money and would need IMF support.

This was an early example of the anti-democratic, depoliticisation that has become a hallmark of the neoliberal era. Politicians appeal to external forces (such as the IMF) to push through policies that damage the well-being of citizens so that they can avoid taking the political flack.

Instead of following Healey and co down the Monetarist path and lying to the British people about the currency capacities of the British government (it could never run out of money), Benn advanced his Alternative Economic Strategy.

Tony Benn who was then Secretary of State for Industry prepared a discussion paper in January 1975.

In his 1989 memoirs – Against the Tide, Diaries 1973-76, he described the plan outlined in that paper in this way:

It described Strategy A which is the Government of national unity, the Tory strategy of a pay policy, higher taxes all round and deflation, with Britain staying in the Common Market. Then Strategy B which is the real Labour policy of saving jobs, a vigorous micro-investment programme, import control, control of the banks and insurance companies, control of export, of capital, higher taxation of the rich, and Britain leaving the Common Market.

At the peak of the crisis in 1976, after the September Labour Party Conference where James Callaghan announced that the Labour Party would follow a Monetarist line, Benn submitted the plan to the Cabinet (October 1976).

Back in July 1976, Tony Benn, as Secretary of State for Energy, challenged the basic notion that Britain would face a “crisis of confidence” unless harsh fiscal cuts were introduced (see CAB 128/59 Original Reference CC (76) Meetings 1-22, 1976 13 Apr-3 Aug ).

He hinted that the Chancellor Healey was just ramming through ideologically-motivated cuts given that the Cabinet:

… had seen no specific financial forecast of the likely size of the public sector borrowing requirement, and no quantitative forecast of the extent to which it would fall as economic recovery proceeded.

He believed that the Tories were fermenting discontent by “aligning themselves with the markets to shake confidence in the Government”.

Benn also noted that the narrative kept changing. First, the workers were told that wage restraint was necessary to control inflation. Then, with wage restraint evident, they were told that strikes were causing havoc among international investors. Then, with industrial action “now at a very low level” they now were told:

… that there would have to be further public expenditure cuts?

The danger was that the austerity would undermine the Social Contract and jettison all the good work the unions had done in moderating their behaviour.

Benn urged the Government to consider alternative approaches to the external deficit without cutting public expenditure in any significant way. Among the policies he floated were:

1. “expand industrial capacity by concentrating imports on industrial re-equipment and restraining imports for consumption” (that is, import controls).

2. Increase taxes on “goods with a high imported content”.

3. Ensure higher profits that arose “from the relaxation of the Price Code were in fact devoted to industrial investment”.

4. Divert public money into areas of high unemployment.

The Left ‘alternative’ proposed by Benn and others to the Monetarist orthodoxy emerging within the Callaghan-Healey Labour Party was a recognition of the intrinsic capacities that a currency-issuing government possessed..

As such, the British government could have advanced the well-being of its citizens and eschewed the prioritisation of the interests of international capital, and by 1976, in particular, the interests of the investment bankers and hedge funds.

Unfortunately, it chose the latter path and paved the way for Margaret Thatcher’s damaging regime that would follow a few years later.

I also document how Harold Wilson had white-anted Tony Benn’s earlier attempt at an alternative path in this blog – The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality,

When Benn’s proposal outlining the alternative path, which was based on such policy changes as import controls (particularly on luxury items), and a national plan to invest in and revitalise British industry, was sent to the Prime Minister on March 24, 1975, Wilson annotated the document in this way:

I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it.

Amazing really.

Fast track to November 27, 2017 and the release by the Tory Business Secretary Greg Clark of – The UK’s Industrial Strategy.

The accompanying Press Release – Government unveils Industrial Strategy to boost productivity and earning power of people across the UK – noted that the “Industrial Strategy” sets:

… out a long-term vision for how Britain can build on its economic strengths, address its productivity performance, embrace technological change and boost the earning power of people across the UK.

Described as a “flagship” strategy the announcement, while not getting much media attention, represents a major ideological shift in Tory politics.

Why?

Because it is an explicit statement that the British state has to be a central player with a major role in planning, managing and stimulating economic activity.

The ‘free market’ will solve allocation problems has been rejected – front and centre – by the release of this strategy.

The Tory British government has now rejected the idea that government should step aside and allow private profit-seeking to drive the future path of the economy.

It has now agreed that the State is central and has to steer investment and build infrastructure to ensure that investment is made in key areas.

The private sector, left to its own devices by New Labour and then the Cameron-Osborne Tory Government has clearly failed to put investment funds into areas that boost productivity.

These governments allowed the financial sector to grow at the expense of productive sectors. As a result, the UK is now a low productivity growth economy with severe compositional imbalances.

Skilled labour and investment is attracted into essentially unproductive, wealth-shuffling activities concentrated in London (finance), while regional and industrial decay is evident elsewhere.

The Industrial Strategy recognises that that more state intervention is required.

It defines “5 foundations” which will be the targets for significant state spending initiatives:

– ideas: the world’s most innovative economy

– people: good jobs and greater earning power for all

– infrastructure: a major upgrade to the UK’s infrastructure

– business environment: the best place to start and grow a business

– places: prosperous communities across the UK

If you mapped these foundations back into Tony Benn’s Alternative Economic Strategy you will see a strong correspondence.

Ideas – mean research and development, and, hopefully, more higher education funding, where innovations and knowledge are mostly born.

People – requires investment in better education (wider participation, inclusion for disadvantaged groups etc) and skill development.

Infrastructure – a recognition that public infrastructure allows private firms to leverage off – crowding-in private investment.

Business environment – encouraging investment.

Places – bringing the social settlement (where people live) into better alignment with the economic settlement (where jobs are). This is an explicit rejection of the New Regionalism that developed under the Blair regime and claimed that there was no need for state regional development strategies because the market would take care off it.

The Industrial Strategy also identifies “4 ‘Grand Challenges'”:

– artificial intelligence – we will put the UK at the forefront of the artificial intelligence and data revolution

– clean growth – we will maximise the advantages for UK industry from the global shift to clean growth

– ageing society – we will harness the power of innovation to help meet the needs of an ageing society

– future of mobility – we will become a world leader in the way people, goods and services move

Again, a sort of ‘picking winners’ approach to industrial development and an explicit rejection that the market knows best where to put investment funding.

I mostly agree with the UK Guardian article (November 27, 2017) – Why this white paper on industrial strategy is good news (mostly) – assessment of the Industrial Strategy.

It points to several weaknesses, which I will leave to you to read about.

The overall point though that:

The key is the welcome recognition that our economy will not succeed unless we are willing to abandon the economic orthodoxy of the past 30 years and give government its proper role. If that can now be accepted, we should all be grateful.

I thought the announcement was interesting in the light of the Brexit debate.

The day after the Industrial Strategy was announced, the CEO of the peak body representing British Universities released a statement (November 28, 2017) – Downturn in UK participation in latest EU research programme statistics – which tried to advance the Remain stance.

I doubt that the CEO had fully absorbed the intent of the Industrial Strategy when this press release was put out.

It echoed the standard anti-Brexit line that EU funding for UK higher education would dry up. As it probably will.

It noted that funding under “Horizon 2020, the current EU framework programme for research and innovation” had fallen for UK institutions.

Apparently this decline in funding participation will stop UK researchers from collaborating with “world-leading experts on life-changing research, with knock-on benefits for the economy, society and individuals in the UK”.

Well, that is simply untrue.

The UK Guardian – so anti-Brexit it doesn’t matter – bought into this myth in their article (December 3, 2017) – Fears grow over EU university funding as grants decline even before Brexit.

We read quotes such as:

– “It is so frustrating watching the country head towards a potential barren land for research”.

– “Ministers need to recognise the damage that their flawed approach to the Brexit negotiations is doing and act quickly to secure our future in European research programmes.”

Universities UK had acknowledged in their press release (November 27, 2017) – Industrial strategy white paper – that the

Industrial Strategy – would provide “increased support for quality-related research”.

Which makes you wonder why the next day they pushed the line that Brexit would kill research funding in the UK and then the UK Guardian elaborated on that lie.

The point is – and I will elaborate further on this in subsequent blogs – the UK government can fund as much research as it likes without any EU contribution.

And as an Australian researcher (who has secured many millions in competitive funding over my career), I have had no trouble collaborating with EU-based researchers, despite not having access to EU-based research funding.

Conclusion

While the language and terms used (emphasis on environmental sustainability, etc) are somewhat different to the Benn vision – reflecting history mostly, the Tory Industrial Strategy is a statement that Benn would not have opposed.

It marks a shift in the mindless, ‘free market’ narratives that governments have become obsessed with in this neoliberal era.

The next challenge is to reeducate these politicians on what currency sovereignty means.

I continue in that role.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Boy, wish Tony Benn was still around. He could sort out the the Blair rabble..

Notable in the Guardian’s Hattersley article was the disingenuous absence of any reference to the fact that he was in fact a Lord.

Nope, it was just plain old ermine-less Roy, temporarily disrobed to avoid the impression of yet another top-down establishment hatchet job on Corbyn.

The Graun is a neo-liberal rag.

I was born in 1973 and grew up in a very political household, with father being a union delegate his entire working life.

Since I was very young, I watched the scourge of neo-liberalism grow bigger and more powerful, then become the dominant force and then virtually crush all other ways of thinking to dust. My entire life has been spent watching all the things I was brought up to believe in continually swept away.

Now middle-aged – could I finally be witnessing the beginning of the turning of the tide? I thought so in 2008 but a savvy social scientist at the time declared “this is not the end of neo-liberalism. No matter how badly it fails it will stagger on and on because there is currently no broadly-accepted alternative socio-economic narrative for the people to embrace”. He turned out to be correct.

But all ideologies run their course. Neo-liberalism has simply failed to deliver for the average person (not that it was ever intended to!) and everybody knows it. The greatest vampire squid in living memory (and beyond) is dying with increasing numbers of it’s former supporters turning away.

I hope I live long enough to see it buried.

One could take the view that the Tories have gone, in the terminology of Stephanie Kelton, from being Deficit Hawks to being Deficit Doves, hence one would have to worry about what their stance would be when circumstances improve, however long that would take. Labour have the potential, though they haven’t yet clearly indicated that this is a line they would take, of being Deficit Owls. In a nutshell, a Deficit Hawk thinks deficits are bad all the time; a Deficit Dove thinks deficits are ok when times are bad and bad when times are good; Deficit Owls thinks deficits in general are irrelevant, that is, that there is no reason to incorporate them into policy objectives. In other words, while the Tories seem to walk the walk, will they ever talk the talk? They seem to utter one view before breakfast and another after lunch.

While anyone with half a brain would agree with you, Bill, that the UK government could fund whatever they chose to fund, the big question is this: irrespective of the recent industrial strategy white paper, would they follow up on their rhetoric? I will wait and see, but I will not hold my breath. I wouldn’t trust this group of Tories to clean my car.

I gave up on Cohen a while ago, while Elliott is frustrating — I keep hoping he will finally get his macroecon right, only to be generally disappointed, though sometimes he is ok.

Healey was a Marxist while at Oxford and used to stand on tables in pubs proclaiming the death of the capitalist class. Judging by his large house on the Sussex Downs with its swimming pool he must have been doing a fair bit of ‘capitalising’ in his day! I can remember an interview with Healey (1980’s?) where he proclaimed that Governments could no longer control markets and that the financial centres were in control.

I suspect the Tories will do as little as possible and offer crumbs from the neo-Liberal table-just enough to make it look like they are doing something -the main problem in the UK is that the voting public are very divided around the two main parties. Polls consistently show a 40% support for the Tories which never shifts with Labour only one or two percent above. So even if Labour get in it will be a slow process shifiting things significantly.

I suspect a lot of stagnation ahead with ossified levels of inequality and food-bank use.

Apologies: I got it backwards. While Tories seem to talk the talk, will they ever walk the walk? Oh, dear.

Mr S, the Grauniad’s recent steeper descent into neoliberal-land, though there are exceptions, seemed to begin after the appointment of the new editor. Though I wouldn’t call it a neoliberal rag, yet. Ms Viner seems to have little macroeconomic nous. On the other hand, maybe she thinks she is acting impartially and providing ‘balance’, along the lines of the Beeb. If she is, she is violating the paper’s own motto, Facts are sacred.

The Guardian is being told what to write and publish in my opinion as evidenced by the Anti Brexit conveyor belt and the recent return to Corbyn bashing despite the conversion of Polly T.

@larry

The Graun seems to mainly concern itself with endless articles on identity politics, plus, lately, overt pro-EU propagandising.

Mostly opinion pieces, very little hard news, especially anything beyond its very narrow fields of interest, and as you imply, macro economically illiterate.

The Scott Trust is now the Scott Trust Ltd, with a board of directors drawn almost exclusively from the world of banking and commerce, so in that sense I regard it as being directed within a neo-liberal framework.

I skim it each day in the same way I used to visit the BBC website: to see if there have been any earthquakes or other natural disasters, or to see whether anyone of significance might have died overnight. For anything else, it’s useless.

@Simon,

You may be heartened by the recent Survation poll showing Labour at 45%, Tories on 37%.

Regarding Healey; I would be deeply suspicious of any conspicuous Communist who was educated and active at Oxbridge. Chances are high that they were co-opted by, and reporting to, one or other of the intelligence services, domestic and/or transatlantic, whilst they were there, and after.

Healey couldn’t have represented US capitalist interests better had he been an employee of the US Government. 1976 IMF loan and biggest ever annual reduction in public spending indeed!

Some Communist!

AndyB, you neglect Owen Jones, who is a Corbyn supporter.

Mr S, I did note the change in the Scott Trust and thought at the time that it probably wouldn’t make much difference. Well … . I agree to a significant extent with your assessment of the lack of data in the paper. Especially since the appointment of Viner, though it was true previously, too.

I didn’t like Healey then and I certainly wouldn’t like him now. I thought his argument supporting the loan was complete bollocks. But I could hardly get anyone to agree with me. I gave up in the end. His reversion, as I would conceive it, reminds me of an inverse of Lewontin’s late conversion to Marxism. He became an intolerant and inflexible bigot. It was a quasi-religious conversion, not unlike the devotion to neoliberal principles, where a small group wins at the expense of others. Of course, the gloss is something else entirely. And, no doubt, some perpetrators actually believe this rubbish.

Corbyn, and most importantly his overall economic objectives will never be accepted by the blairite wing of the party. They would rather lose to the Tories than see him win on a genuinely social democratic platform. I actually think June hurt the Blairites more than the Tories, they were genuinely gutted Labour weren’t destroyed.

The chipping away however started again almost immediately after the election, there was no hiatus. And when Blair says Brexit can be reversed and he will work tirelessly to achieve that, that has two meanings (attempt to reverse Brexit, bury Corbyn).

Its astonishing in some senses that Labour polled over 40% – Corbyn et al were attacked from the extreme right, one nation Tories, ‘wet’ Tories, the centre (what was left of it), the centre left and right across the media spectrum, almost all newspapers, most television and radio – and most importantly, nearly 80% of the members of parliament of his own party !

I should say i’m not Corbyn’s biggest fan either, but he’s absolutely the best hope right now the party has got in terms of taking it in the direction it was originally created for. Look at all the other social democratic parties in Europe and worldwide who have supped from the neoliberal kool-aid in the last 30 years. They’re all dead, dying or are in a hopeless position.

Hardly ever get any analysis from US media on the UK.

thanks for the article.

Larry. I’m afraid I regard Jones as a lightweight celebrity lefty. Mostly harmless.

Thanks for this really helpful analysis of the UK 1970s. So often in the UK, people bring up the 1970s as an example of “how it will all go wrong” and why supposedly we can’t have anything other than a Thatcherite/Blairite government. I was also interested by something SWL wrote about that period https://mainlymacro.blogspot.co.uk/2017/01/the-uks-1976-imf-crisis-in-light-of.html . He agrees with MMT analysis about foreign currency denominated government debt and floating exchange rates. There seems to be divergence though where he discusses interest rates, inflation and the output gap. Am I right in understanding that the MMT position is that interest rates should have been zero throughout that period? Should tight fiscal policy (eg higher taxes) have been used to curb inflation? To what extent should high inflation have been tolerated? Should it just have been viewed as an inevitable readjustment to the oil shock or whatever and been allowed to go to >25% (and that with zero interest rates???). JWMason often makes the point that labour shortages force innovation and investment that deals solves output gaps and a healthy economy comes from having an output gap. That makes sense to me but I’m unsure as to how far that can be pushed.

“To what extent should high inflation have been tolerated? ”

High inflation is an indication that you have insufficient competition in the market segment. Firms that are in competition struggle to put their prices up because a quantity adjuster will always outcompete a price adjuster. That’s the sweet spot you’re trying to hit.

The UK in the 1970s, and unfortunately Corbyn’s position now, is that ‘jobs must be protected’. That’s entirely the wrong approach. The correct approach is that there must always be another job available.

If you ‘protect jobs’ you are by definition protecting firms from competition and failure. When you do that the whole market process stops working as it should. Labour has yet to ditch the ‘job for life’ concept and the idea that firms will somehow act in the ‘correct’ way if you plead with them enough. Both those concepts do not work in a market economy.

If we’re going to use capitalism we want it raw in tooth and claw. Capitalists should be slugging it out like prize fighters. The job of the containment system around the nuclear power of capitalism is to harness that power and protect ordinary people from damage. Once you have more job offers than people the gig economy becomes the talent economy and it starts to work properly.

Andy, you are right, but that doesn’t make him a bad guy necessarily.

Andy and Mr S, Chakrabortty is on good form today. He is writing about something he knows well, and he lambastes the ‘zombie Blairites’ with a scathing account of what they are doing in Haringey. Today’s article carries further two others updated on 27 November.

Neil, I would qualify your use of high inflation as an indicator. Lack of sufficient competition is only one way high inflation could take place. But I know you know this. I agree that an available job is a better hedge against high inflation than job protection, in most circumstances anyway.

“Lack of sufficient competition is only one way high inflation could take place.”

I’m not so sure. For inflation to occur there has to be a price rise, and somebody has to be prepared to pay it. Price rises don’t happen by magic.

The trick, I think, is to make sure the only sellers market is in labour and then only at a clearance price. If your region’s buyers, particularly government buyers, then treat parsimony as a religion you’ll find the sweet spot. Although I’ll admit that’s somewhat like trying to sustain a fusion reaction – easy to describe in theory but rather challenging to achieve in practice.

Great blog post

Its maddening that a bennite industrial policy is being introduced by tories after 30 year of him being derided.

@stone

oil shock led inflation

Could of been dealt with via investment in research

In developing tech which reduces reliance on oil for industrial and consumer purposes.

@Neil Wilson, that’s an interesting point you make about it being important to ensure plenty of jobs rather than protecting existing jobs. Are there specific policy changes that Labour could make that would redress that? My understanding is that Labour are wanting grass roots policy suggestions and would listen to your ideas.

In the specific 1970s case, I’m not so certain that 1970s inflation could have been entirely delt with by better competition within the UK. The oil price was being set outside the UK and much of the inflation in the UK came from that. Eventually we got North Sea oil but it took a few years to get going.

“Are there specific policy changes that Labour could make that would redress that? ”

That’s what the Job Guarantee does. It creates an elastic supply of jobs in all local areas and thereby directs government spending automatically to areas with greatest need.

“The oil price was being set outside the UK”

That’s precisely what I mean about making sure there isn’t a sellers market. With overseas resources you need multiple competing supplies from nations that will not act in unison. The Opec Cartel created a sellers market – at which point you have to start using tools like rationing until you can break that cartel with substitution or new supply sources.

You certainly can’t deal with it by putting interest rates up.

@Neil Wilson, I’m not so sure whether the OPEC set oil price was “too high” with the pre-OPEC price being “fair”. At some level, it seems dumb to have had a 1960s oil price level so low that oil was burnt in power stations. How can you determine a “fair” price for a finite natural resource? To me it just seems to be a question of organisational power. If Saudi Arabia etc have no power, then the oil price could drop to the cost of extraction for the easiest oil field (ie the Saudi’s). If they can organise, then they can dictate the price until production outside the cartel sets the price.

What seems clearer is that the UK was faced with a transition from a low oil price to a higher oil price and that increased cost had to somehow be born by firms and employees and consumers and creditors. I guess the inflation and high interest rates stemmed from a conflict over who would bear the brunt of that pain. The 1970s get talked about as calamatous but to some extent things looked to have worked out fairly well. I guess the Thatcherite backlash suggests plenty of people didn’t think so though. I’m still unclear what your prescription for the 1970s would have been. If we take it that you wouldn’t have got North Sea (and USA) oil production ramp up any quicker, then is the only key difference that you would have had zero interest rates? Then creditors would have born more of the burden then they did at the time. Looking back at the 1970s, creditors don’t look to have done so well. Interest rates were high but didn’t match inflation. It’s not so clear to me that their fate at that time wasn’t “fair”. I’d be very interested if somehow having a zero interest rate policy could have led to lower inflation and less conflict. Is that claimed?

You mention rationing as the way to deal with intractable supply shortages. I totally agree with that in extreme situations such as war or famine. I’m not so sure how that could have been applied to the 1970s oil shock. Perhaps petrol and diesel rationing might have caused more use of trains etc and shorter supply networks. But the oil would still have been just as expensive, rationing or no rationing, since the UK market was not setting the price. It is quite a different situation to the WWII situation where a hard supply constraint was set by U-boat blockades etc.

I stopped reading Cohen years ago. In fact there are very few Guardian/Observer columnists I can bear to read these days. I keep an eye on Larry Elliot’s column, but clearly he doesn’t totally get it.

And Owen Jones also made the “borrowing” mistake in a piece recently. (and he wasn’t originally an unreserved Corbyn fan).

.

…

.

I’m not a fan of Roy Hattersley, but to be slightly fair to him, I don’t think he particularly liked what Blair did to the Labour party. I remember clearly his writing around that time that his views hadn’t changed – he was always more or less on the right of the party, but that Blair had moved the party so far to the right, that, somewhat to his own dismay, he now found himself (at least somewhat) on the left of the party. (Obviously not as far left as Benn & Corbyn, of course). In one respect he differed markedly from Blair in that he was still proud to call himself a (democratic) socialist.

.

…

.

@Bill, I posted the following question in a comment to your blog article about your presentation to the Labour Party which you wrote back in September, although I only posted my comment in the last few days, so perhaps you didn’t get to see it. Since you are writing about the Labour Party here, I will take the liberty of repeating it here in shorter form:

Did you manage to get to speak to any of the Labour Party leadership while at the conference? If so, did you manage to give them (or sell them!) a copy of your latest book?

A large part of Labour’s problems in the 1970s had their origins in the 1960s. Labour came to power in 1964 (I think) committed to Dirigisme, state interventionism and economic planning. The effort came to nothing due to opposition from the BofE, Treasury and within British industry itself. The economic reformers who had promised to transform Britain in the “white heat of technology” during the 1960s” included Harold Wilson but by 1976 many of them had bought into the myth that Britain was in terminal relative economic decline. Denis Healy once joked that if Britain was destined to become a member of the third world, at least it would do so as a member of OPEC due to the discovery of North Sea oil. Tony Benn really was a lone voice in the wilderness.

The turn to neoliberalism in the mid-1970s was an attempt to take the wind out of the Thatcher opposition’s sails. An early example of the Third Way’s much vaunted triangulation strategy if you like.

Inflation is more broadly a sign of competition within the economy.

the oil cartel won for a period everyone else attempted to protect their end ,oil is

used througout the economy inflation was inevitable.Other providors of raw materials (steel for one)

had similar ‘wins’ at the time.

Raising interest rates is an attempt to reduce spending from loans into the economy an

attempt at reducing the intangible demand pull inflation but this too is in the context of conflict

in the economy.

A cartel is a weapon to win the conflict but the conflict was is and shall always be there.

The search for a sweet spot, an equilibrium is the economists ‘ stone