It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

Germany – a most dangerous and ridiculous nation

Germany’s domination of the EMU is clear both in political and economic terms. The current political impasse within Germany will not change that. Once resolved the on-going government will continue in the same vein – running excessive fiscal surpluses and huge external surpluses. It can sustain those positions because it dominates European policy and can force the adjustment to these overall ‘unsustainable’ positions onto both its own citizens (lowering their material living standards), and, more obviously, onto citizens of other EMU nations, most noticeably Spain and Greece. If it couldn’t bully nations like Greece, Italy, Spain and even France, Germany’s dangerous domestic strategy would be less effective. If all EMU nations followed Germany’s lead – then there would be mass Depression throughout Europe. This dangerous and ridiculous nation is a blight. Only by exiting the Eurozone and floating their currencies against the currency that Germany uses can these beleaguered EMU nations gain some respite. When the Europhile Left come to terms with that obvious conclusion things might change within Europe.

I have written about Germany several times and the following blogs are a selection as background to today’s blog:

1. Massive Eurozone infrastructure deficit requires urgent redress.

2. Wolfgang Schäuble is gone but his disastrous legacy will continue (October 16, 2017).

3. The chickens are coming home to roost for Europe’s so-called powerhouse (August 10, 2017).

4. More Germans are at risk of severe poverty than ever before (July 6, 2017).

5. German trade surpluses demonstrate the failure of the Eurozone (April 24, 2017).

6. The European Commission turns a blind eye to record German external surpluses (October 31, 2016).

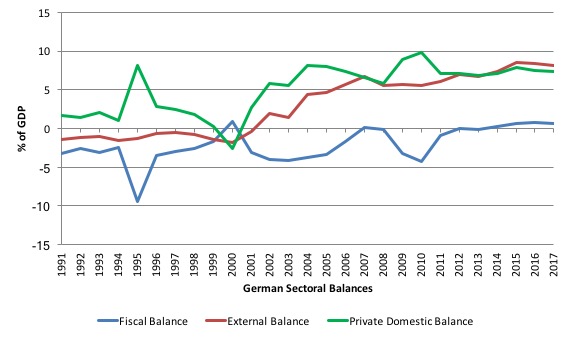

The following graph (using IMF WEO data) shows the sectoral balances for Germany from 1991 to 2017 (the last year is estimated).

It is an extraordinary graph really in the context of Germany’s integral role in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Germany is part of a currency union and its outcomes are much more closely tied to the fortunes of its EMU partners than say a nation, such as Australia, which has its own currency and floats it on international markets.

What you see are two distinct EMU periods, when Germany was in gross violation in one way or another of the Treaty rules (laws).

The first violation came soon after the EMU started.

Germany violated the Stability and Growth Pact fiscal rule (maximum deficit 3 per cent of GDP) along with France.

Germany was one of the first nations to transgress the rules along with France. By early 2002, German economic growth was fairly subdued with a further slowdown likely. It was also absorbing the fiscal consequences of German reunification.

On January 30, 2002, the European Commission, acting under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) rules, gave Germany an early excessive deficits warning and demanded a balanced budget position be met as soon as possible despite understanding that if the German economy slowed any further, the deficit would rise further.

A similar narrative was followed for France, which was also enduring recession.

Sure enough, the mindless fiscal austerity that Germany adopted within the recession-biases of the SGP caused its economy to slow further. Millions lost their jobs as a result, while others increasingly found their jobs becoming more precarious and their wage prospects suppressed.

If there was ever a time for reflection on how damaging the EMU structure could be, then this period should have been it.

I document in detail what happened as the European Commission and Council came into conflict over this issue in November 2003 in this blog – Options for Europe – Part 97.

I also covered the history of these violations in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale.

Essentially, Germany conspired with France (Schröder and Chirac) to set the Council (via Ecofin) against the Commission to force the latter change the rules relating to the SGP (forced through via the Treaty of Lisbon), which avoided Germany being punished for three consecutive years of Treaty violation.

The point was that the violations were sensible – the deficits were above the 3 per cent threshold because of the impacts of Germany reunification and recession – and it was the application of the rules were irresponsible.

It was the rules that made no sense, and endure today even more perniciously – just look at Greece. But Germany’s position showed its own hypocrisy (being a major agent in establishing the harsh, unworkable rules in the first place) and the untenable nature of the core EMU policy infrastructure.

The second violation has emerged since the GFC in the form of the external surpluses combined with fiscal surpluses, which have created serious imbalances within the Eurozone.

It is not overstating the case to say that the increased poverty and hardship for citizens within Europe is directly related to the German government’s obsession with fiscal and external surpluses and its intransigence when confronted about this.

Germany has become a dangerous yet ridiculous nation.

While the Financial Times article (December 22, 2017) – The fiscal surplus that Germany should spend – referred to “Germany’s fiscal surplus” as an:

… a chronic embarrassment of riches …

I would prefer to refer to it as an embarrassing example of policy vandalism and an illegal assault on the rules that Germany has signed up to follow.

Why illegal? Because it is directly related to Germany’s violation of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure, which specifies under its so-called Scoreboard Indicators that the “major source of macroeconomic imblances” includes a:

3-year backward moving average of the current account balance as percent of GDP, with thresholds of +6% and -4%

So the upper warning threshold (for an external surplus) is 6 per cent of GDP.

Imbalances are meant to trigger “the alert mechanism report (AMR)” – the latest being issued on November 22, 2017 – 2018 European Semester: Alert Mechanism Report.

We read that “large current account surpluses persist … in Germany and … continue to exceed the threshold as they have done for several years … Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands are currently recording surpluses well above what can be explained by economic fundamentals”.

Relatedly, we read that “The growth in unit labour costs in a number of net-creditor countries … remained overall moderate in 2016, having cooled somewhat in Germany against the backdrop of subdued wage dynamics, despite the tightening labour market.”

Further, “The combined large surpluses of Germany and the Netherlands account for almost 90% of the current level of the aggregate euro-area surplus”.

And:

Some Member States are characterised by large and persistent current account surpluses that while reflecting their strong competitiveness reflect also, to a varying degree, subdued private consumption and investment … The large and persistent surpluses may imply forgone growth and domestic investment opportunities. In addition, the shortfalls in aggregate demand bear consequences for the rest of the euro area in a context of still slack in activity and below-target inflation.

And:

Germany was experiencing macroeconomic imbalances, in particular related to in its large current account surplus reflecting excess savings and subdued investment.

Sanctions?

None.

The facts from the graph above are obvious:

1. Germany has been running current account surpluses above the allowable threshold since 2011 – averaging 7.5 per cent of GDP since then and averaging 8.3 per cent of GDP over the last three years.

2. It has been running fiscal surpluses since 2014, 0.6 averaging per cent of GDP since then.

3. The two aggregates are intrinsically linked via national income changes (see below)

4. There are no policy shifts foreshadowed that would suggest anything is going to change much.

The causal links between the balances is clear.

By suppressing domestic demand – public and private consumption and capital formation investment – through its attacks on wages growth and fiscal austerity, Germany stifles imports.

For example, since the German mark disappeared (March 2002), exports have grown by 106.7 per cent while imports have grown by 101.4 per cent (noting that in the March-quarter 2002, there was already a substantial external surplus – 1.9 per cent of GDP).

What happens if a nation exports more than it imports (ignore, for simplicity, the income side of the current account)?

The net outflow of real goods and services would be accompanied by accumulating financial claims against the rest of the world.

This is because the demand for the nation’s currency to meet the payments necessary for the exports would exceed the supply of the currency to the foreign exchange market to facilitate the import expenditure.

How might this imbalance be resolved? There are a number of ways possible.

A most obvious solution would be for foreigners to borrow funds from the domestic residents. This would lead to a net accumulation of foreign claims (assets) held by residents in the surplus nation.

Another solution would be for non-residents to draw down local bank balances, which means that net liabilities to non-residents would decline.

Thus a nation running a current account surplus will be recording net private capital outflows and/or the central bank will be accumulating international reserves (foreign currency holdings) if it has been selling the nation’s currency to stabilise its exchange rate in the face of the surplus.

Current account deficit nations will record foreign capital inflows (for example, loans from surplus nations) and/or their central banks will be losing foreign reserves.

Large current account disparities emerged between nations in the 1980s as capital flows were deregulated and many currencies floated after the Bretton Woods system collapsed.

European nations such as Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland were typically recording large and persistent current account surpluses and with a significant proportion of their trade being with other European nations, the imbalances grew within Europe as well as between Europe and elsewhere.

Think about the sectoral balances arithmetic. If a Member State achieve a balanced fiscal outcome and is sitting on the current account surplus threshold (6 per cent), then its private domestic sector will be saving overall 6 per cent of GDP.

Where will those savings go?

I have discussed how Germany maintained its external competitiveness once it could no longer manipulate the exchange rate in previous blogs.

Please read my blogs – Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home and – Germany should look at itself in the mirror – for more discussion on this point.

The savings may go into the domestic economy if there are profitable opportunities to invest. But in Germany’s case, its whole strategy was based on suppressing domestic demand (Hartz reforms, wage suppression, mini-jobs etc), and so profitable investment opportunities were limited in the German economy.

As a result and capital sought profits elsewhere.

The persistently large external surpluses which began long before the crisis (and 6 per cent is large) were the reason that so much debt was incurred in Spain and elsewhere. German investors pushed capital externally.

Germany is clearly supplying large flows of capital to the rest of the world.

The combination of domestic demand suppression and huge external surpluses means that Germany’s outflow of capital is ridiculous.

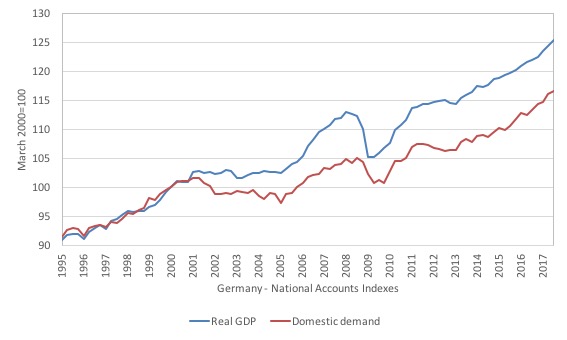

Have a look at the following graph, which show the evolution of Germany’s real GDP and domestic demand (consumption and investment) since the March-quarter 1995 to the September-quarter 2017 (Eurostat National Accounts data).

They are indexed to 100 at the March-quarter 2000.

Since that time, GDP in Germany has grown by 25.3 per cent, whereas domestic demand has grown by just 16.5 per cent (in real terms).

There are two very interesting things about the graph apart from the divergence between total spending (GDP) and domestic-based spending (domestic demand).

First, you can see the suppression of domestic demand began soon after the inception of the euro – the Hartz devastation.

Second, look what happened after 2011, as the fiscal austerity moved into top gear. While real GDP grew on the back of the growing exports, domestic demand fell between June 2011 and June 2013, further exacerbating the Eurozone crisis.

That evolution was the result of deliberate policy positions taken by the German government.

By deliberately constraining the standard of living of its citizens and undermining its own public and private infrastructure, the German government has also damaged its EMU partners.

To resolve this problem (which is a massive imbalance between domestic saving and investment), Germany requires higher domestic demand and faster wages growth both to boost the very modest consumption performance and to attract investment into the domestic market.

It also could stimulate public spending – say, to start the long process of restoring quality to its public infrastructure which has been seriously degraded by the austerity mentality of successive German governments.

But such a change would be at odds with the mercantile mindset that dominates the nation because it would reduce the competitive advantage that Germany enjoys over other nations that have treated their workers more equitably.

And, the European Commission has not acted to stop Germany gaming the system even further.

The European Commission’s – Macroeconomic imbalance procedure – is an integral part of its economic and fiscal policy coordination governance and:

… aims to identify, prevent and address the emergence of potentially harmful macroeconomic imbalances that could adversely affect economic stability in a particular Member State, the euro area, or the EU as a whole.

But, as we have learned, the European Commission is good at bullying the weaker nations, who feel inferior members of the

‘European Project’, but won’t lay a glove on Germany.

That is why realistic progressive reform in the Eurozone will not be possible.

On May 10, 2017, the German Finance Ministry took the (extraordinary) step of publishing an English-language article on their WWW site (under Financial Markets) – The German current account in the context of US-German trade.

The article was an attempt to deflect criticism of its export-led obsession and was published in tandem with the German Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The Finance Ministry wrote:

Germany’s current account surplus has been garnering criticism for years … [this] … joint position paper … explains the reasons behind Germany’s current account surplus and outlines the fiscal and economic policy options.

It states that:

As a member of the European Union, Germany does not pursue independent trade policy: Trade policy falls within the competency of the EU. The German government’s policy is in line with all international trade agreements and treaties; in particular Germany policy complies with WTO requirements.

Which gives the impression that they are passive adherents to externally set rules – depoliticisation in action here.

No mention of the aggressive internal devaluation policy (so-called Agenda 2010) that Gerhard Schröder followed in the early days of the Eurozone (Hartz attacks on social welfare and the creation of Minijobs).

We read that “Fiscal and economic policy in Germany aims at strengthening domestic growth and creating favourable conditions for a competitive economy.”

Clearly, if that was true then the external surplus would decline as imports rose and rising wage levels altered real exchange rates (measures of international competitiveness).

But the German government is always keen to massage facts.

For example, it claims that:

… domestic demand has been the main driver of German growth for several years now.

Which belies reality.

Since Germany resumed growth in the June-quarter 2009, real GDP has grown by 19.1 per cent up to the September-quarter 2017. The contribution of domestic demand to that growth has been just 5 percentage points.

Further, household consumption spending, which in many nations is above 65 per cent of total spending (GDP), in Germany it is now down to 52.8 per cent in real terms.

Since 1995, it has dropped by more than 5 percentage points.

Capital formation (investment in productive capacity) has also fallen significantly over recent years as a share of total spending.

The huge external surpluses are then not reinvested domestically because home sales growth is suppressed.

The impact on other nations is clear.

The huge German external surpluses are mirrored in other nations as external deficits, which drain spending and growth. To ensure employment and output growth is maintained, the non-government sectors in these nations then have to increase their external debt levels and run fiscal deficits.

While that is not necessarily an issue for currency-issuing nations (depending on private debt levels), it is a really huge issue for Germany’s EMU partners, such as Spain, Italy, Greece, Portugal etc.

The external and fiscal deficits for those nations are unsustainable within the shared currency zone. We have all seen the consequences of that as the GFC unfolded.

It is true that the “the German current account surplus is mainly the result of market-based supply and demand decisions by companies and private consumers on global markets.”

But it is equally true that government policy that deliberately suppresses wages growth and creates precarious employment, while at the same time, cutting expenditure growth in areas of public infrastructure development, also reduce imports and create few local private investment incentives.

While the German Finance Ministry claims that “German fiscal and economic policy have no direct influence on, such as temporary factors including the euro exchange rate or global commodity and energy prices” it ignores the fact that Germany’s trade is so dominant in overall Eurozone relations with the rest of the world that it influences on the trajectory of the euro is clear.

If the German government embarked on a large infrastructure project and significantly pushed up wages growth, then imports would rise, the current account would fall and the euro would fall somewhat.

Even the majority of German people think that would be desirable.

In a Deutsche Welle report (November 11, 2016) – Merkel pledges budget increases for infrastructure in election year – we learn that:

In a poll carried out by public broadcaster ARD in September, 58 percent of the electorate supported spending additional tax revenue on infrastructure, while only 22 percent favored debt reduction and 16 percent called for tax cuts.

I have previously written about the infrastructure crisis in Germany – Massive Eurozone infrastructure deficit requires urgent redress.

As the Financial Times article (cited above) notes:

Within a single currency area, where the peripheral economies have had to undertake a real depreciation to restore competitiveness, a relative rise in German prices means the adjustment can be achieved without painful reductions in prices and nominal wages elsewhere.

Which negates the arguments of the likes of Wolfgang Schäuble and the vast majority of German economists that inflation would accelerate if the fiscal surplus was lower or wages restraint was relaxed.

And, the FT concluded:

But in a country desperate for investment it would be better all round for Germany to ease back on public finance surplus fetishism and make more creative use of its bounty.

Conclusion

Germany’s domination of the EMU is clear both in political and economic terms.

The current political impasse within Germany will not change that. Once resolved the on-going government will continue in the same vein – running excessive fiscal surpluses and huge external surpluses.

It can sustain those positions because it dominates European policy and can force the adjustment to these overall ‘unsustainable’ positions onto both its own citizens (lowering their material living standards), and, more obviously, onto citizens of other EMU nations, most noticeably Spain and Greece.

If it couldn’t bully nations like Greece, Italy, Spain and even France, Germany’s dangerous domestic strategy would be less effective.

If all EMU nations followed Germany’s lead – then there would be mass Depression throughout Europe.

This dangerous and ridiculous nation is a blight.

Only by exiting the Eurozone and floating their currencies against the currency that Germany uses can these beleaguered EMU nations gain some respite.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Just came across this book, which is of some interest to the topic here, some historical background-

Tobias Straumann, Fixed Ideas of Money: Small States & Exchange Rate Regimes in 20th-Century Europe, Cambridge (2010)

In particular, it is about small open economies: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. Many critics of MMT or FF (wrongly) assert that it only works for big economies, or just the US. While the author hardly seems to be an MMTer, or a complete fan of floating this is interesting:

“The comparative analysis shows that, for most of the twentieth century, the options of policy makers were seriously constrained by a distinct fear of floating exchange rates. Only with the crisis of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1992-1993 did the idea that a flexible exchange rate regime was suited for a small open economy gain currency….”

Germany couldnt control Europe through 2 world wars so it turned to trade and economic domination.

Under the EU-regime Germany has finally managed to achieve what Hitler tried so hard, but failed at. The complete subjugation of Europe under German interests. Why are the affected nations allowing this to happen?

Hello,

Great blog, thanks.

I have a bit to do with Germany and so find articles on it interesting.

I often ask myself what is the point of a large current account surplus if the surplus is going to be vented away in tax? The German workers make wonderful products that other nations want to buy, the products are exchanged for electronic money credits that are then deleted in taxation instead of enjoyed as income by the worker who made the product.

To exacerbate this process with internal austerity so that your average German citizen goes without in order to keep imports down and wages low is even worse.

Who benefits? Other countries that receive top notch manufactured products sans the pollution that goes into making them? German export business owner elites receiving super profits while the balance of the population receive austerity?

Alan,

you say:’electronic money credits that are then deleted in taxation’ which makes it sound like a 1 to 1 relationship-but surely those extra credits function differently in relation to whether it is a Euro credit or a foreign currency ($,£)?

Ans surely a significant part goes to those (the rich) with a lower propensity to consume -so some must stay as foreign treasuries or stashed away in a ‘paradise island.’?

I’m not very knowledgeable re. external sector monetary systems -so if you could expand on that it would be helpful.

Regards,

Simon

Dear Bill

Germany can’t dominate the EU or the Eurozone. The reason why Germany can get its way is that most Europeans outside Germany see Germany as an example to be emulated rather than as an culprit to be denounced. Remember, most people are mercantilistic in their thinking. They assume that exports are intrinsically good and that trade surpluses are a sign of economic health.

To be fair, it should be pointed out that Germany has 3 partners in crime in Europe: the Netherlands, Denmark and Switzerland. Here are their current-account surpluses as a percentage of GDP:

Netherlands Denmark Switzerland

2102 10.2 6.3 10.5

2013 10.2 7.8 11.6

2014 8.9 8.9 8.7

2015 8.3 9.2 11.2

2016 8.7 7.9 9.4

Granted, Denmark and Switzerland aren’t members of the Eurozone, but they do most of their trading with other EU countries. Norway also runs huge current-account surpluses, but they have all that oil. They are the Saudi Arabia of Europe.

The price of Bitcoins is going through the roof. It would be interesting to read your views about that. My view is that Bitcoin is a libertarian folly and that the skyrocketing price of Bitcoins is a speculative bubble.

Regards. James

Excellent article, thank you Bill

Within the neo liberal paradigm Germany is a success and to be emulated.

Just doing what all the other nations are trying to do.

When macro economics is just scaled up micro economics then sectorial balances

are irrelevant .

Germanys’goals are no different to most nations within the paradigm.

It may be impossible that all nations run surpluses but that is the madness of

neo liberalism not some inherent German colonial dominating mindset which is

simply prejudice.

Been reading ‘Hierarchy Theory: A Vision, Vocabulary, and Epistemology’ by Hal and Allen. In this book a natural complex systems, for a system to be stable it must not only be efficient short to medium term it must be able to with stand disruption events. That is often happens in mass extension events, e.g. the dinosaurs not being able to with stand a disruption event, such as a meteorite hitting the earth, while the mammals could with stand the disruption. The question seems to be, in the long term could social unrest such as, mass youth unemployment and wealth inequality create a disruption event that would make the system topple.

Maybe the American voting in Trump as president could be seen as a disruption event?

Hello Simon,

The role of taxation is to vent off excess aggregate demand. A current account surplus is an income flow for the exchange of real resources. If the income flow is excessive, or in Germany’s case there is an internal austerity drive on to keep imports down thru low incomes, or both, the income flow is vented off in taxation like a gas flare on an oil rig. Real resources effectively exchanged for nothing at the macro level.

Alan Longbon “I often ask myself what is the point of a large current account surplus if the surplus is going to be vented away in tax? ”

It’s important to remember that Germany is a currency user. Taxation is not cancelled currency units as it would be in a monetarily sovereign nation. The government actually does need, spend and save revenue.

Right. It’s a little unfair to criticise Germany in these terms, and rather dangerous to talk about the EU/Eurozone succeeding where Hitler failed, or similar comments. In fact, in the post-war period, before neoliberalism took hold, Germany had a pretty good record in social democratic terms. True, with its history of hyperinflation, it was always going to be financially conservative, but became pretty liberal socially and (for a former dictatorship) quite a model of democracy.

Industrious both literally and metaphorically, hard-work, efficiency and thrift are seen as social and national virtues. And far from world domination, Germany originally was opposed to a widening of what became the EU. (It wasn’t even all that keen on EMU originally).

I’m not saying that modern, neoliberal Germany hasn’t bullied Greece (and probably behind the scenes Spain, Italy and maybe even France). Well for better or worse, those countries are in the same “club” and have to obey the rules as Germany sees them, I guess. Obviously it would be better if Germany relaxed, or better still got rid of its neoliberal outlook, and it would be better for Greece if it left the “club” (and probably also better for Spain and Italy). As for France, I think France and Germany are probably stuck with each other for the foreseeable future. A Franco-German Eurozone would probably work pretty well I reckon. Throw in the Benelux countries, and you’ve almost got the original “Common Market” which is probably how it should have remained.

“Under the EU-regime Germany has finally managed to achieve what Hitler tried so hard, but failed at. The complete subjugation of Europe under German interests. Why are the affected nations allowing this to happen?”

For a more nuanced view? See:

“Conjuring Hitler: How Britain and America Made the Third Reich”, and/or

“A Century of War: : Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order”

As a german, i am afraid i have to say, that i can’t see any sign of change coming from within my country.

The german media is telling everybody almost uniformly that, economically speaking, we almost reached heaven. Germany is experiencing a sustainable economic upswing and thanks to structural adjustment, the rest of the EMU is slowly but steadily recovering. The biggest dangers are seen in an overheating of the economy, protectionist tendencies in world trade and EMU-countries slowing down their reforms.

Every now and then, there is a critical report on stagnating wages, missing investment in infrastructur, low investment generally, growing poverty, international imbalances, youth unemployment in greece etc., but rarely do you see anybody connecting the dots.

Misleaded media coverage of economics is fuelled by corporate control over the media on the one side and neoclassical economists serving as experts on the other side.

From 2002-2007 i have experienced what they teach in economics departments of a german university first hand (university of Bonn): Money multiplier, crowding out, IS-LM, intertemporal optimisation etc. with a strong focus on calculus vs “thinking”.

The miss leaded perception of the majority of Germans about the state of “the economy” is of course also the main reason, why it’s hard for me to imagine a policy change. The social democrats themselfes are mostly neolibeal and no different from the conservatives. In the end, they executed the hartz reforms. But while they are struggling to claim their part in the “success” of the reforms, they are still beeing made responsible for their social costs: precarious work, poverty, infrastructure degradation etc. There is also no sign of change from within the party. They are still trying to square the circle and make neoliberal politics work for their clientel. But unlike other countries its unlikely, that a progressive alternative majority will emerge out of that dilemma.

The former socialist party “Die Linke” still struggles with its role in communist east germany. There was no real cut with its past and a political party that was responsible for repression and societal stalemate is not considerd an alternative by most. Part of the party is also overly utopist. Rigorously critizising capitalism might not be a good choice, if you have no realistic alternative at hand and people get the idea, that your utopism in the end might bring you dystopia (DDR 2.0) instead. Together with their strong focus on the refugees-“crisis” – the topic that still dominates german political discourse – die linke has little chance of winning majoritys. And even if they succeded, the economic problems of germany and the EMU are only understood by a fraction of its leading figures. The stance that we only need to redistribute wealth, we have to be “good europeans”, or that capitalism is the root evil for everything is still very strong.

So in the end its deadlock everywhere and some reason to be pessimistic and expect change to come only from a major crisis.

Great blog

But why does Germany and Netherlands and Switzerland have such a productive lead on the other european countries?Why do the German working classes experiencing demand repression not resent this so much.

Germany,since 2007,has had a 40% increase in real estate values.Clearly a lot of these financial surpluses held by equity owners of those profitable industrial german firms are being recycled into domestic mortages as well.

@Basta FarI:

Hi,

As you are a German, perhaps you can offer an opinion on the following:

I gather that Chancellor Merkel has not been able to form a workable coalition so far, following the recent election.

So far as I could see, from the election numbers, a left-wing coalition could have (theoretically) been formed from the SPD, Die Linke, and The Greens.

ISTR that the SPD and the Greens were in coalition once before.

Is an SPD, Die Linke, Green coalition absolutely out of the question?

Are Die Linke just beyond the pale, as far as the SPD are concerned?

Thank you for your thoughts on this.

@ Mike Ellwood

Following the last elections, social democrats (SPD), socialists (die Linke) and the greens combined do not have a parliamentary majority anymore and since the “liberals” (FDP) will never form a government together with the socialist, there is no realistic chance of a government without the Cristian Democrats being by far the biggest player.

And if we can trust the polls, new elections would only make things worse for the partys on the left.

But even if there was a left majority in parliament – like in the previous term -, especially the SPD seems not ready to coalise on the federal level with die Linke.

Die Linke is still stigmatised for its past in the DDR. The aim to leave the NATO and the “appeasement” against Putin are seen as irresponsible and certainly do not help to show that die Linke is not the SED anymore. The SPD also considers (the economic program of) die Linke as populist. Not surprising, since the SPD still claims to be especially responsible. In the end, it was the SPD who executed the Hartz reforms under great cost for it self and thereby layed the foundation for germanys economic “succes”.

Anyways, the Cristian Democrats will determine german economic policy probably for quite some time and they have made clear what they consider to be “sound” economic policy again and again.

I hope i will be proven wrong, but i think german EMU “partners” should seriously reconsider leaving the EMU.

@Mike Ellwood

there is no left majority in Germany. What one should understand as for the German political system is that all relevant institutions, not only political partys, but all of the relevant unions, all mainstream medias, private as formally public ones, most of the scientific elite, support the German economic model aka the German form of neoliberalism. This general support is enhanced and confirmed by the de facto hegemony Germany has obtained in the EU- and Eurozone. As far as that model is concerned all those relevant institutions act as ‘Staatsparteien’, whose main responsibility is to create the conditions to preserve that very model. As I wrote, this is true of all relevant partys except for Die Linke. Essentially , there is in Germany a Neoliberal Block including CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP, Grüne and AFD. The only weak oppositon being Die Linke. The Greens have become kind of a green FDP, the have steadily moved to the right. So no, there is really no hope for a change in Germany, at least as long as it succeeds in imposing its model and in presenting it to its own people as a success.

@Basta FarI and @salvo,

.

Thank you both very much for your comments.

I think I must have mis-read the numbers in the German elections, or miscalculated.

.

Germany’s de-facto hegemony: One might think that the less successful countries in the EZ (which is most of them) might realise that German neoliberalism is the problem (and not the solution). Especially after Cyprus and Greece were hung out to dry. But apparently not.

A German comedian used to put it like this: “In Germany, you just can’t convince a majority of the people to vote for you when you offer a policy strategy that benefits more than 80% of them”.

In my opinion, the most frustrating thing is to confront the average german with macroeconomic reality. He then will not only insist that export surpluses are indicator of economical strength, but solely due to the superior quality of german products and that nobody is forcing anybody to buy them. Furthermore, he tends to consider people/governments in the deficit countries lazy, unefficient and unwilling to work as hard as himself. He will probably even complain that all of Europe is living on Germany’s expense and that the worst thing would be if his government continues collecting refugees and wasting money on social boons. He eventually takes a rampage on the ECB taking on his savings by low interest policy and feels insulted by how all the world always blames the german.

In the end, this is just what media, politicians, think tanks and economists are telling him all day.

There is no way in hades that leading German politicians can actually believe the phoney economic cover stories that are disemminated by major institutions in Germany. The policies that the German government follows are clearly not in the best interests of Germany or Europe. The obvious question is why are these policies followed then. To possible answers spring to my mind. One is that German leaders are hostages to hidden forces that are beyond their control. Think about this. When a distant star is circled by a planet that planet is to small for us to see. But the gravatational pull that planet exerts on the star can be detected. We can not directly see the star but we can deduce that it is their based on indirect observations. A second possible answer that springs to mind is that German leaders are partners in crime with leaders from the US, UK, Japan, France and possibly other countries adopting policies that are a form of class warfare against the non wealthy.

In a comment that I made yesterday I pointed out that German pensions are enimic compared to pensions in the USA and possibly if not probably compared to other countries as well. The German answer to this imbalance is not to fund better pensions through deficit spending. It is to encourage Geman workers to fund their own retirement through private retirement plans. For Americans something like 401k plans. This strategy is enhenced by frequently touting the unsunstainability of the government retirement system due to Germany’s aging population. That scares the population in to investing. This strategy forces the worker to to bear the risks of the market. More importantly in locks the worker in to the capalist system. That is ultimately no doubt why the system has been promoted.

The workers feel compeled to take part because the state system might not be there when they retire or be there only to a very miminal extent. But once they start putting their own hard earned money in to a private system they would not want that system to fail or even be devalued because then their money fails or gets devalued with it.

Lets see a show of hands, who thinks that this “investment” retirement system was created with benign intent? Who thinks that it was a deliberately designed policy to blackmail workers in to supporting an unsustainable system to the very end? Look behind you. See the smoke? As we get lead further and further in to the desert the bridges over the canyons behind us are being burnt to make it harder and harder to go back to civilization.