It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

IMF finds the Eurozone has failed at the most elemental level

The IMF put out a new working Paper last week (January 23, 2018)) – Economic Convergence in the Euro Area: Coming Together or Drifting Apart? – which while they don’t admit it demonstrates that the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) has failed to achieve its most basic aims – economic convergence. The stated aim of European integration has always been to achieve a convergence in the living standards of those within the European Union. That goes back to the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which established the EEC (Common Market). It has been reiterated many times in official documents since. It was a centrepiece of the 1989 Delors Report, which was the final design document for the Treaty of Maastricht and the creation of the EMU. The success or otherwise of the system must therefore be judged in terms of its basic goals and one of them was to create this convergence. The IMF finds that the EMU has, in fact, created increased divergence across a number of indicators – GDP per capita, productivity growth, etc. It also finds that the basic architecture of the EMU, which has allowed nominal convergence to occur has been a destabilising force. It finds that the Stability and Growth Pact criteria has created an environment where fiscal policy has become pro-cyclical, which is the exemplar of irresponsible and damaging policy implementation. Overall, the conclusion has to be drawn that the EMU, at its most elemental level, has failed and defies effective reforms that would make it workable. It should be scrapped or nations should exercise their own volition and exit before it causes them further damage.

Before we consider the IMF Working Paper, there was an interesting news report in Politico (January 23, 2018) – Europe’s eastern tigers roar ahead – which documented how despite the ‘politics’, which have brought “Central and Eastern EU members … [into] … Brussels’ bad books”, these “economies have become some of the bloc’s star performers”.

They have grown dramatically in recent years “more quickly than major economies in Western Europe”.

We read that:

A visitor returning to these countries after a few years away will find new highways, modernized buildings, and a plethora of foreign investment. At the same time, low unemployment is boosting consumer confidence and domestic demand … Governments from Warsaw to Budapest and Bucharest are spending big on programs that are highly popular with their voters but that may ultimately put pressure on budgets.

What is going on in these nations is quite complex and deserves further analysis.

But the point is that these nations have not become blighted by the austerity bias that rules in the Eurozone Member States and has created such dysfunction and failure (elevated unemployment rates etc).

That insight conditions what we discuss next.

Go back to April 17, 1989 when Jacques Delors as the Chairman of the Committee for the Study of the Economic and Monetary Union, released their – Report on economic and monetary union in the European Community.

In Chapter 1, at the outset of the Report, we read that in 1974, the European Council had decided to adopt a principle:

… on the attainment of a high degree of convergence in the Community and the Directive on stability, growth and full employment.

After claiming that the European Monetary System (EMS), which governed exchange rates between 1979 and 1998, had laid “the foundations for both a downward convergence of inflation rates and the attainment of a high degree of exchange rate stability”, which was a rather breathaking revision of history (and ignored the role that capital controls played which were anathema to the growing consensus with Delors’ Presidency of the Commission), the Delors Report said:

Although substantial progress has been made, the process of integration has been uneven. Greater convergence of economic performance is needed. Despite a marked downward trend in the average rate of price and wage inflation, considerable national differences remain. There are also still notable divergences in budgetary positions and external imbalances have become markedly greater in the recent past. The existence of these disequilibria indicates that there are areas where economic performances will have to be made more convergent.

The Report went on to say that:

… monetary union without a sufficient degree of convergence of economic policies is unlikely to be durable and could be damaging to the Community

The EMU would thus:

… aim at a greater convergence of economic performance through the strengthening of economic and monetary policy coordination within the existing institutional framework

That was the aspirations for Stage 1 – the preliminary machinations before the euro was fully adopted.

The Delors Report told us that the:

The integration process thus requires more intensive and effective policy coordination framework of the present exchange rate arrangements, not only in the monetary field but also in areas of national economic management affecting aggregate demand, prices and costs of production (emphasis in original).

The whole European narrative in the early 1990s that bullied reluctant politicians into accepting the 1992 Maastricht Treaty was (in the IMFs words):

… that by giving up monetary autonomy, euro area countries would gain greater economic stability and higher growth, as the elimination of exchange rate uncertainty and lower borrowing and transactions costs would lead to more trade, labor, and capital flows.

The Delors Report didn’t just focus on so-called ‘nominal’ convergence (inflation, interest rates, deficits, debt) criteria. The clear intent of the Report was to hold itself out as a continuation of the process started with the Treaty of Rome (EEC) (Treaty establishing the European Economic Community).

The 1957 Treaty of Rome, the specific goals included laying “the foundations of an ‘ever closer union’ among the peoples of Europe” and to “reduce the economic and social differences between the EEC’s various regions”.

The IMF Report (cited above) interpreted this as saying that:

… the Delors Report laid out income convergence – a gradual and sustained decline in differences in per capita income levels across countries – as an explicit objective of the monetary union.

The original Delors Committee might object to that given that there is no mention of ‘per capita incomes’ in their Report.

But the Report did hold out that the proposed EMU would support policies which were not only “geared to price stability” but also to “balanced growth, converging living standards, high employment and external equilibrium” – the latter set being ‘real’ criteria and consistent with the IMF interpretation.

The neoliberal mantras that drove the Delors Committee claimed that by introducing a common currency, there would be ‘market processes’ that would ensure these real convergences would occur.

We were told that (in the IMFs words):

… labor could flow from lower wage countries to higher wage ones, producing convergence in the marginal product of labor.

The Delors Report asserted, in this regard, that:

… measures designed to strengthen the mobility of factors of production and the flexibility of prices would help to deal with such imbalances.

The neoliberals believed that the ‘single market’ would help Europe spread the benefits of the union to:

… help ensure that the gains from the monetary union are shared and thereby foster social cohesion. Furthermore, income convergence can help garner support for common insurance mechanisms to address shocks, by reducing concerns that transfers between countries could be permanent.

Of course, the reality was different to all this ‘free market’ rhetoric and the EMU created conditions for divergence rather than the stated goal of convergence.

But it is no surprise that (as we will see) the IMF have found limited convergence across the 19 Member States.

At the outset, it was a pretense. These nations were never going to converge, which was the point made by those invoking the Optimal Currency Area criteria, that some believe have to be present to provide a sound basis for an effective federation.

The pre-euro convergence farce

In my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – I detailed the farcicial nature of the pre-euro convergence process (Chapter 12) where smokescreens and denial were the preferred tools to convince the neoliberal, Europhile Groupthinkers that things were on track and Stage 3 (adoption of euro) was justified.

For example, in 1997, France, Germany and Spain had deficits above 3 per cent and could not really appeal to the special circumstances clauses as a way out.

Further, the public debt ratios in Germany and Spain were above the 60 per cent threshold and had been increasing since 1995. By contrast, although Italy’s public debt ratio was well in excess of the criteria, it had been falling. Further, Belgium was in a similar situation to Italy.

Tactically, Germany could not isolate Italy without pleading some special case for Belgium, which of-course, it attempted without success.

The Germans at the time believed that “Italy should never have been accepted into the common currency zone” (I document all sources in the book). The Italian government was engaging in accounting gymnastics (with the Banco d’Italia) to produce falsified data, which suggested they were meeting the deficit criteria (3 per cent of GDP).

Everyone knew it was false.

Germany too, was lying. In late 1996, Finance Minister Waigal was accused by the Opposition SPD of “lying and deceiving the public” over the state of the nation’s finances.

SDP leader Gerhard Schröder argued that Stage III should be delayed while Germany sorted out its own economic challenges, which included rising unemployment.

In early 1997, we saw the extent to which Germany would go to manipulate the debate. Finance Minister Waigel astounded even his fellow Finance Ministers at a meeting in the Netherlands by saying that “I have never nailed myself on the cross of 3 percent. When I said in the past ‘3 percent means 3 percent’ I did not necessarily mean 3.0 percent”.

The hypocrisy was amazing for those, like me, who were anti-EMU and followed the debate closely at the time.

While Germany tried to make out that the ‘accounting tricks’ were a problem of other nations (France, Italy, Spain, later Greece), they were up to their necks in manipulating their public accounts.

Waigel privately crafted his own plan to ‘cook Germany’s books’, which looked very similar to those same creative accounting plans deployed by France and Italy.

Only a refusal by the Bundesbank to artificially inflate its contribution to the Finance Ministry (via revaluation of gold reserves) brought his deception unstuck.

But all the jockeying on data to meet the convergence criteria (inflation, interest rates, deficits and debt) gave way to reality.

The final decision on who would enter the EMU was always going to be political and the convergence criteria were really a smokescreen, a sort of delusional security blanket designed to placate the German public and the conservatives elsewhere that the process was disciplined and sustainable.

There was no economic logic, just a set of arbitrary numbers grabbed out of the air, which were then backfilled with a series of spurious ‘economic’ reports that claimed to represent these numbers as ‘economic knowledge’. They were never that. They were always just ideological statements about the Monetarist disdain for government activity.

All this meant that the convergence criteria had to be watered down.

In effect, they all agreed to fudge the books and bend the rules they had set for themselves, because the rules themselves were impossible to meet while still maintaining anything like politically acceptable unemployment rates.

The upshot was that eleven nations were deemed to have met the convergence criteria and would enter the EMU.

The politicians had demonstrated a spectacular capacity to bend their own rules but there were limits if they wanted to retain any semblance of credibility. Greece was at that stage beyond these limits.

But not for long!

Some statistical cheating with the aid of Goldman Sachs saw Greece come into the fold a few years later.

Following this saga at the time gave me a sense of how dislocated from the underlying reality the Eurozone movement had become.

The most distressing aspect though was the way the European Left bought the con hook-line-and-sinker. Delors, after all was a ‘socialist’ – an indication of when a word loses all meaning.

The Europhile Left fell into this sort of mindless spell that progress was being made and the introduction of the euro was a symbol of that progress.

They were told by outsiders (like me) that this was folly and would end badly. But their capacity to reason was way below the blindness from their rose-coloured-Europhile glasses.

And they hurried to beat the conservatives to the front of the queue – to ‘walk the plank’ and fall into the abyss of austerity and dysfunction.

And still, they defend the system. You still see stupid tweets from so-called Europhile Leftists who think there is no democratic deficit in the Eurozone, who hold hopes for progressive reforms, who think Europe is still on the right path.

They fail to see the reality.

IMF report on post-euro convergence.

The pre-EMU convergence criteria were all ‘nominal’ in nature.

The IMF note they were:

… focusing on nominal and fiscal indicators of harmonization, including: i) inflation; ii) long-term interest rates; iii) exchange rate stability; iv) the fiscal deficit; and v) the government debt-to-GDP ratio. The criteria were aimed at achieving price stability and lowering the dispersion of inflation rates while reducing excessive deficits before locking the exchange rates.

Remember, the designers of the EMU had become infested with the false ideas of Monetarism, which claimed that if a nation attained price stability that it would automatically achieve optimal growth rates and full employment (real criteria).

The obsession was then with nominal criteria as a path to achieving real concerns.

They wanted to discipline fiscal policy “to reconcile a common monetary policy with decentralized fiscal policies, preventing spillovers from national policies”.

The austerity bias was built-in to the whole Maastricht architecture – to satisfy the neoliberal (Monetarist) preference for reduced government activity and influence.

At the time, critics argued that the link between the nominal criteria and actual economic outcomes was flawed.

It was also pointed out that:

1. If everyone had the same inflation rates (a key convergence requirement) then all the adjustments for the lack of exchange rate adjustment would have to be borne by domestic wages and employment if there were productivity differentials. That would be a very damaging process for nations with lower productivity growth.

History has borne those concerns out.

2. A common interest rate was hailed “as a dividend from monetary union” but as history has shown us, was a dangerous source of instability – viz Spanish real estate boom on the back of low interest rates as a result of German dominance in the monetary policy setting.

Germany required low interest rates to address recession early in the EMU period.

3. The Stability and Growth Pact criteria has created an environment where fiscal policy has become pro-cyclical (contracting when the non-government sector was also contracting its spending).

The SGP requirements do not give government sufficient flexibility to meet large negative cyclical events.

Further, given the conduct of the ECB since the crisis (in effectively funding government deficits to keep the Eurozone from collapsing), the IMF are correct in concluding that the “no-bailout clause, which was to ensure that governments did not engage in fiscally irresponsible policies … lacked credibility”.

The architecture of the Eurozone was thus deeply flawed – at the most elemental level.

First, the economic cycles were not symmetrical across the Member States, which meant that the EMU was “making countries worse off with a common monetary policy than outside the monetary union”

Second, “idiosyncratic business cycles leave a tough burden for national fiscal policy to offset asymmetric shocks” and the common SGP rules made it impossible for individual states to achieve that offset.

Further, there has been little evidence of sufficient labour mobility to transfer workers from high unemployment areas to those nations where the negative shock of the crisis had less impact.

The IMF Report concludes (among other things):

1. “Inflation rates converged substantially before euro adoption, but did not align further thereafter” – since 1998, there has been very little additional convergence in inflation rates.

The “persistent inflation differentials contributed to competitiveness gaps” (via differential real exchange rates)

2. “Nominal interest rates also converged, but the convergence was undone during the crisis” – the IMF agree that with persistent inflation differentials, the common interest rates meant that “real interest rates fell sharply in some countries and overshot convergence”, which “fueled credit booms and domestic demand, re-enforcing inflationary pressures”.

These differences worked against ‘real’ convergence.

3. “contrary to expectations, income convergence among EA-12 countries slowed after Maastricht and subsequently came to a halt” – this was only contrary to the neoliberal claims.

Critics of the EMU proposals were always saying that there would not be further income convergence once the common currency was introduced.

The IMF say that there has been further “divergence since the crisis, reversing the initial narrowing in income dispersion”.

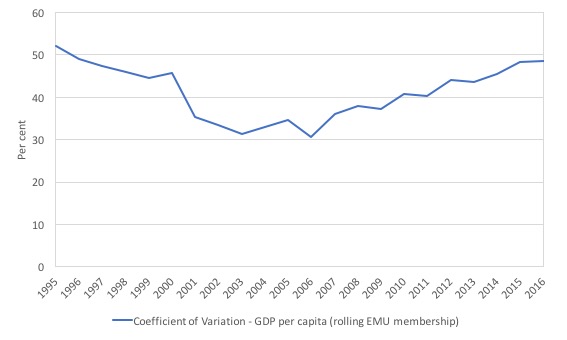

The following graph shows the Coefficient of Variation (standard deviation adjusted for different means) for GDP per capita (a measure of living standards) for the Eurozone Member States from 1995 to 2016 (most up to date data).

The sample is rolling in the sense that it expands as each new accession to the common currency becomes operational.

On this simple measure alone, the Eurozone has not delivered any sense of convergence. The inequalities in GDP per capita have increases since 2002 and are now at pre-Eurozone levels.

The IMF present other empirical evidence that supports the divergence rather than convergence conclusion.

4. “Contrary to expectations, there was no productivity catch-up following the introduction of the euro … countries with low initial productivity have had consistently lower TFP growth and experienced a sharper slowdown over recent years” – again the expectations were generated by delusional Europhiles not those who were grounded in their understanding of what the EMU would achieve.

5. “A larger fall in investment and employment since 2008 further added to the post-crisis divergence in economic growth” – all courtesy of the application of the key EMU rules (SGP, Fiscal Compact etc).

6. “While business cycles have become more synchronized during EMU, the size of these fluctuations has diverged … the divergence in amplitude means that the optimal degree of tightening or loosening of macroeconomic policies would differ for different countries”.

So trying to impose common fiscal rules on nations experiencing vastly different amplitudes in spending variations in their economies will lead to worse outcomes than if the nations were free to pursue their own responses to cyclical variations.

But with a common currency, unless the ECB is empowered to fund any fiscal deficits that the nation states feel are essential to counter asymmetric negative spending shocks in the non-government sector, a Member State might violate the fiscal rules but then find that the bond markets will not provide them with the ‘foreign’ currency (the euro) that they need to remain solvent.

It is a circular dysfunction.

7. “Germany’s financial cycle has become increasingly disconnected from the others … a large and growing variation in amplitudes across national financial cycles. In particular, financial cycles were strongly amplified in Spain, Ireland, and Greece, with standard deviations close to five times the euro area average.”

What does that mean? A financial cycle is proxied by movements in the cost of credit and residential property prices.

There were massive capital flows flowing from “core country banks to … Spain, Ireland … and … Greece” which then set up the bank crises.

In turn, the harsh bailout provisions imposed on Greece, were designed to ensure that the exposure of the Northern (French, German) banks to the Greek crisis was reduced and the Greek people paid the price. A substantial proportion of the bailout payments that the Greek government has been forced to make were to protect these banks not help the Greek economy.

On adjustment mechanisms that the neoliberals claimed would “help income convergence and countries’ capacity to adjust to shocks within the single currency”, the IMF found that:

1. “the envisaged adjustment mechanisms under monetary union have been insufficient to support convergence, and have in some cases contributed to divergence.”

2. “Intra-euro area trade is substantial, but has not increased as much as predicted … the effect of EMU on trade has likely been small” – there have been little ‘competitive’ gains from the internal devaluation forced on to nations – a point I have made regularly since the crisis began.

Further, the Europhile Left continually talk about the benefits of the common currency in reducing frictions at the border (currency changes) as if the macroeconomic gains of this are large.

The IMF finds that trade gains have been virtually non-existent.

3. “The adjustment impact from intra-EU labor mobility has also been modest” – “language, cultural and administrative barriers” remain and will always remain.

This is one of the major reasons, the EMU can never really work. Germans do not think of themselves as ‘Europeans’ united with Greeks, for example.

A cultural sharing has to be present in effective federations.

4. “Capital flows, meanwhile, increased substantially, but financed investments in low- productivity sectors and drove unsustainable booms” – we have discussed these above.

5. “At the same time, foreign direct investment (FDI) flowed disproportionately to Central European countries, rather than other euro area countries” – Germany’s suppression of its own domestic demand, which created reduced opportunities for profitable domestic investment, not only saw capital flows to the ‘south’ within the EMU.

But German industry has been busily creating a low-wage supply chain for its manufacturers in the weaker Eastern European nations.

Refer back to the introduction – where non-Eurozone European nations to the east have been booming in recent years.

Conclusion

The IMF think the answer is to fast track structural policy initiatives (cutting pensions, further deregulation, etc) and “Recalibrated euro area fiscal rules to allow for greater countercyclical policies, together with a common fiscal capacity”.

I agree with the second not the first of these solutions.

The main problem is not a lack of productivity among some member states. The sort of problems we have seen post Euro were not there before.

The main problem is that the Member States ceded their currency sovereignty and then were put in a straitjacket by the Treaty so that fiscal policy became pro-cyclical – and thus has worsened any non-government sector spending decline.

Of course, the Europhile Left think that can be corrected (with unemployment insurance schemes etc). Little do they know.

What score out of 10 would we now give the Eurozone on those grounds some 18 years after the inception of the common currency?

I would give it 1/10 and only because there is more exchange rate stability because they wiped out the Member State currencies.

But the instability that dogged European currencies since the inception of the Common Market has now been shifted (via internal devaluation) into massive divergences in standards of living across the Eurozone.

In that sense, I would give the Eurozone a negative (less than 0/10) rating.

MMT University Logo competition

I am launching a competition among budding graphical designers out there to design a logo and branding for the MMT University, which we hope will start offering courses in October 2018.

The prize for the best logo will be personal status only and the knowledge that you are helping a worthwhile (not-for-profit) endeavour.

The conditions are simple.

Submit your design to me via E-mail.

A small group of unnamed panelists will select the preferred logo. We might not select any of those submitted.

It should be predominantly blue in colour scheme. It should include a stand-alone logo and a banner to head the WWW presence.

By submitting it you forgo any commercial rights to the logo and branding. In turn, we will only use the work for the MMT University initiative. It will be a truly open source contribution.

The contest closes at the end of March 2018.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved

How long do you give the EU to survive, Bill?

There’s obviously no intention to drop neoliberalism, although it might be watered down a bit.

I see no recognition of the role MMT could play in getting the house in order.

So I think we can drop any pretence of gain there. Probably it can’t come soon enough!

Dear Bill

Your writings have been a valuable primary source for my first faltering steps in understanding macroeconomics.

There is no shortage of economic experts out there with forthright views along neoliberal, monetarist, Thatcher-style ‘There Is No Alternative’ lines. As you know, the public discourse tends to be dominated by these views, with right wing thinktanks getting on to many radio and TV debates on economic topics, constantly pushing their agenda in what seems a concerted propaganda machine.

For myself, trying to educate myself on economic matters, it is difficult to get a realistic, unbiased picture of how a modern industrial economy works. I don’t have time to investigate source data and there are obvious flaws in the field of classical macroeconomics that make me reluctant to get a standard textbook on the topic.

I now have to see if I can justify the cost of your own MMT textbook!

In the meantime, I continue to work through the logic of the concepts and explanations in your blogs, and from other sources. This radio program from the BBC was broadcast today, “Shaking the Magic Money Trees” http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09pl66b (possibly only available in the UK). This program discussed some key concepts made familiar to me through the MMT approach: the power of the sovereign currency issuer, the ineffectivesness of QE as a rescue from the GFC.

I hope these mainstream media programs will help prise open the stranglehold that the neoliberals have on public conceptions of economics. It helps when someone like myself (a non-expert) can point to “acceptable mainstream” back-up when I introduce MMT concepts to friends, colleagues and relatives.

Looking forward to the development of the MMT University courses!

Steffen,

I spent a Summer reading Mankiw’s Principles of Macroeconomics cover to cover in the spirit of “know your enemy” (for economists are often the enemies of genuine progressives saying “it can’t be done”). Full of MV=PQ with assumed full employment and loanable funds, IS/LM, money multipliers, crowding out, uselessness of fiscal policy in small open economy, barely a mention of Keynes and the paradox of thrift/fallacy of composition etc.

I almost enrolled in a university macro paper.

Then I decided not to. Reason – coming across MMT, Wray, Kelton, Mosler and Mitchell. Waste of money on non-knowledge to study mainstream macro in a mainstream university.

Better to be self-taught.

Hard to argue against a negative score if the result is worse than before.

Excellent thorough blog post