Yesterday, the Bank of Japan increased its policy target rate for the first time in…

Lower bond yields do not save the Japanese Government money

I was going to write about the situation in Timor-Leste after its national elections were held on Saturday. But I will hold that over for another day as I get some more information. So today, I think we can learn a lot from an issue raised in the Bloomberg article (May 14, 2018) – Kuroda’s Stimulus Saves Japan $45 Billion, Easing Debt Pressures – which discusses the QE program in Japan and introduces several of the basic errors that mainstream financial commentators make when discussing these issues. The article traverses all the usual suspects including the misconception that numbers in official accounts are ‘costs’ to government and that smaller numbers in official accounts mean the government can put larger numbers in other accounts than it might have been able to. These articles are as pervasive as they are erroneous. Hopefully, as the precepts of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) spread and are understood more journalists will endure scrutiny of the rubbish they write and the public commentary and debate will progress towards a more reasonable – realistic – appraisal of what is going on in the world of finance and money. This article is one of the worst I have read this year so far. And there have been some real terrors!

The sub-titles to the articles were:

Driving down borrowing costs is saving the government money

But low rates hurt savers, pensioners and even the BOJ itself

In the first case, there is no sense that the government ‘saves’ its own currency.

In the second case, it is true that lower yields provide less income to holders of the bonds, which might include “pensioners” but to take it further and suggest that the BOJ is in the same boat is to invoke the ‘household budget’ metaphor, which is wrong at the most elemental level.

We will explain that presently.

The article’s main argument goes like this.

1. The Bank of Japan’s “massive monetary stimulus has saved Japan’s government about $45 billion in borrowing costs, helping the world’s most indebted developed nation pay for its debt pile”.

How so?

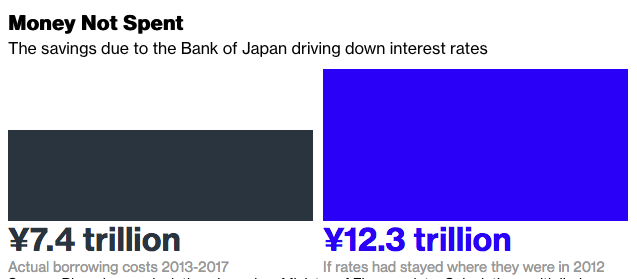

This graphic is provided.

So they worked out the outstanding debt liabilities by maturity and multiplied them by the average yield for each maturity in 2012 and compared them with the actual yield in 2018.

They think this allows them to say that the difference between the blue and black rectangles represents ‘saving’.

The heading is more accurate – the difference is ‘money not spent’.

But for a sovereign government the concept of saving is not applicable.

For an entity in the non-government sector, say a household, the act of saving is equivalent to foregone consumption. We save to expand our future consumption possibilities and are prepared to sacrifice current consumption to earn compound interest on the financial assets we accumulate via that foregone consumption.

That compound interest means – in a stable inflation environment – we can have more later through saving.

So you can easily see that when we talk about saving in this way that there are some underpinning notions.

Most importantly, we realise that for a given income flow for a non-government sector entity, expanding future consumption possibilities requires three elements to be present:

1. That there will be available real goods and services at some future time period to satisfy our future consumption expenditure.

2. That price rises do not outpace the growth in the nominal value of the financial assets we store our savings in.

3. That there is a financial constraint on the entity such that they must sacrifice now to gain more later.

The first element also applies to a currency issuing government. While it is not intrinsically financially constrained in its spending capacity it can only purchase what is for sale in its own currency.

For example, a national government can always provide first-class health care as long as there are sufficient doctors, nurses, medicines etc available to cater for that goal.

The second element affects governments too but not as a constraint in the same way it impacts on households. Ultimately, a non-government entity can only purchase the real equivalent of their nominal income.

So the real equivalent in average terms is the nominal income deflated (divided) by the price level. Simplifying, if a person has an income in dollar terms of $1,000 per week and there is only one commodity available for consumption and its price is $100 per unit, then the real equivalent of that income is 10.

If the price was to rise to $200 per unit, then the real income drops to 5.

Thus the purchasing power for an individual depends not only on the level of nominal income they enjoy but also on movements in the prices of goods and services they purchase.

One could envisage a situation where the inflation rate outstrips the gains in compound interest earned on a person’s saving, which reduces the future consumption possibilities.

For government, inflation does not constrain its real spending capacity as it can for a non-government entity.

It would simply mean that the nominal value of a government’s spending outlays for a given basket of goods and services would rise.

So if the government bought 20 items that currently sell for $10 now. Its outlays would be recorded in the public accounts as $400 if it maintained the same orders (quantities) but the product it was buying doubled in price.

A nominal adjustment but not a real constraint.

Finally, the third element is inapplicable to a sovereign government.

Such a government can, in each period, purchase whatever is for sale in its currency, including all idle labour, irrespective of what its fiscal balance was in past periods.

Which is not to say that the fiscal balance of previous periods doesn’t have implications for the desired fiscal balance in the current period.

I say that because if fiscal policy has been properly calibrated in the past then the spending space that the government has available will be less without any shifts in taxation policy because all available resources will be productively engaged.

To see what I mean by proper calibration, please read this blog post – The full employment fiscal deficit condition (April 13th, 2011).

Please also read the following introductory suite of blog posts – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – to learn how Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) constructs the concept of fiscal sustainability.

In other words, given saving is the act of expanding future consumption possibilities (spending), the concept has no meaning when applied to a currency-issuing government that faces no financial constraint on its spending.

All the Bloomberg article is really telling us, in relation to the Japanese government is that some officer(s) in the Ministry for Finance are typing smaller numbers into various accounts than they were in 2012.

In terms of its impact on the holders of the government bonds the shift in yields downwards reduces their nominal incomes and that is likely to have an impact on their spending patterns.

Which, in turn, is likely to mean the government deficit has to be larger to offset the decline in non-government spending, unless the external surplus increases to create that offset – or a combination of the two.

Because the Bloomberg journalists start from the wrong premise their deductions that follow the empirical world they are describing are also false.

So we read:

Those savings are about enough to pay for Japan’s defense spending for a year, and were possible because the Bank of Japan’s massive bond purchases have driven borrowing costs to around, or even below, zero. As finance ministry bureaucrats plan next month’s medium-term economic plan, how much the nation can borrow, and how sustainable the existing debt is, will be a key question.

Whether those questions are “key” in the next plan is unlikely. The Ministry of Finance officials know full well that Japan can continue to service any outstanding liabilities for time immemorial. They are not stupid.

They also know that should their operational matching of debt issuance to continuing flows of net public spending (deficits) read a point where the private bond markets are saturated with public debt then the Bank of Japan has all the capacity it needs to take up the slack.

The only consequence of a discrepancy between the targeted yields and the market expectations of future yields (that is, the bond traders considered rates would rise eventually) would be that the Bank of Japan would end up owning all or most of the targeted Japanese Government bonds.

In other words, no consequence.

The bond traders might boycott the debt issues and the central bank would then take up all the volume on offer. So what? This just means that the private buyers would be missing out on a risk-free asset and would have to put their funds elsewhere. Their loss!

Eventually, if the government bond was the preferred asset the bond traders would realise that if they didn’t take up the issue the bank would. End of story – the rats would come marching into town piped in by the central bank resolve.

Please read my blog post – The last eruption of Mount Fuji was 305 years ago – for more discussion on this point.

Moreover, trying to match the lower interest payments (lost non-government sector income) with items of government expenditure is fraudulent.

The inference that these lower payments made it “possible” for the Government to allocate the funds to the defense area is ludicrous.

Nothing of the sort was made possible.

The Japanese government could fund all the military needs it desired (given real resource availability) whether it was paying 10 per cent on its bonds or zero per cent.

There is no sense in the statement that by sending out less flows in the form of interest payments on outstanding debt that the Government has more ‘money’ to spend.

The article then traverses the usual scaremongering by telling its readers that Japanese:

… general government debt will be the highest in the developed world at about 2.4 times the size of gross domestic product

Sure enough that is a fact.

Is it relevant. Not at all.

The bond markets consider JGB to be “the widow-maker” which refers to the fact that anyone who tries to bet against the bonds (short-selling etc) will lose big time.

As the Financial Times article (September 5, 2017) – The fears about Japan’s debt are overblown – noted:

… despite two decades of warnings about fiscal Armageddon, a debt crisis never arrived. It never even came close, despite shocks on the scale of Lehman Brothers and the Tohoku earthquake.

Further, why didn’t the Bloomberg article also tell the readers that once we take into account the foreign financial assets that the Japanese government owns the net public debt is around 113 per cent of GDP.

Neither figure is relevant to an assessment of the Japanese government to service the debt or maintain its continuous fiscal deficits.

The Bloomberg article also dives head first into the myths about the Bank of Japan balance sheet.

They say that the lower yields on Japanese government bonds engineered because “the BOJ has replaced the market in setting bond yields” is:

… also cutting into the net income of the BOJ itself, which in turn means it can’t pay as much money each year to the government as it once did. While the BOJ is meant to send most of its surplus to the government each year, it has been reducing that payment so it can increase the amount it has in reserve to cover any future losses on assets purchased as part of the stimulus program.

The accounting gymnastics involved here are basically irrelevant to any real capacity the central bank or the Ministry of Finance possess.

The fact is that the government may be transferring via accounts less from the right pocket to its left pocket.

They may have rules that say that if financial assets the central bank holds lose value then they have to transfer some numbers from one account to another.

And any number of voluntary and largely meaningless accounting conventions.

The facts are:

1. The left pocket’s ‘loss’ of income from the right pocket doesn’t constrain the expenditure capacity of the Japanese government one yen!

2. There is no sense that the central bank can run out of money, which means a financial loss (marking down numbers in its balance sheet) has no fundamental meaning. A central bank can trade with negative capital forever should it wish to.

3. Intergovernmental transfers (between central banks and treasuries) are accounting structures. They do not give or take spending capacity from the government.

Please read my blog posts:

1. The consolidated government – treasury and central bank (August 20, 2010).

2. The US Federal Reserve is on the brink of insolvency (not!) (November 18, 2010).

3. Better off studying the mating habits of frogs (September 14, 2011).

4. The ECB cannot go broke – get over it (May 11, 2012).

Conclusion

These articles are as pervasive as they are erroneous.

Hopefully, as the precepts of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) spread and are understood more journalists will endure scrutiny of the rubbish they write and the public commentary and debate will progress towards a more reasonable – realistic – appraisal of what is going on in the world of finance and money.

Real Progressives Interview today

Earlier today I had a talk to Steve Grumbine from Real Progressives in the US. We covered a lot of issues in the 80 minutes and you may find it interesting.

Thanks to Steve for inviting me on his show and all the listeners who were active in the discussion.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The neoliberal emotive language: ‘driving’, ‘driven’ interest rates down implying work. More accurately they should be saying BOJ ‘set’ the interest rate.

Aside from the usual errors. Its almost as if they finally acknowledge bonds market don’t dictate interest rates but then the author always wants to reframe back into the neoliberal narrative… introduce the double think by saying: “That means it will pay more when rates do start rising.”

Training wheels back on for bloomberg.

I always have fun telling bond vigilante aficionados that should put their money where their mouth is and short JGBs.

Silence.

“Japan is culturally different” they say.

A bilbo blog fan here. After Samuelson in the 60s, then trying to get an alternative in the 70s/80s via Marxist ecs., ..some reading of Mandel, and others; MMT is quite an insight.

As a contact point, I thought I may have been pounced on here by likes of Michael Potter, Steven Hamilton, as I’d stuck my newbie neck out a bit.

https://twitter.com/PaulHenry524/status/996171022918299648

Ex post facto I ran it past Stephen Hail, who waved it through. I’ll probably increase my risk next time, and fall flat on my face. ((-: (I try not to bother him, but made an exception here…)

Who said economics couldn’t be exciting.

Paul