It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

The Australian Labor Party is still stuck in its neoliberal denial stage

Yesterday, the Federal government released their so-called – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) – which is their half-yearly review of the fiscal policy settings. Unsurprisingly, the Treasurer was crowing about the shift towards surplus with booming company tax revenue. With a federal election coming in the next 4-5 months, the Government will now offer tax cuts to entice people to vote for what has been one of the worst governments in our history. The fiscal contraction that is going on at present is totally unwarranted from an economic perspective. The problem for Australians is that the other side of politics – the Labor Party – is no better. It is a sad state of affairs when a political system is dominated by two neoliberal parties. One of them claims to be progressive but every day just reinforces the conservative myths about the fiscal capacities of government. Welcome to Australia.

I analysed the May Fiscal Statement in this blog post – Australian fiscal statement 2018-19 – an election stunt, limited economic coherence (May 10, 2018).

Not much has changed.

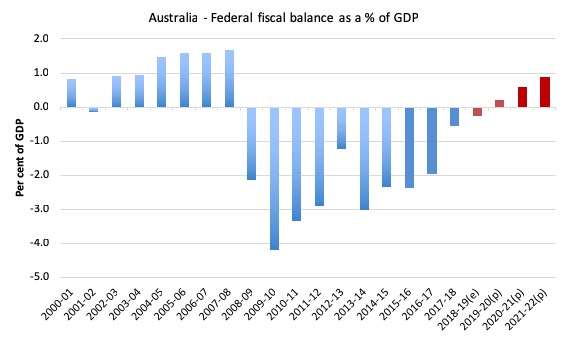

The following graph shows the Australian government’s fiscal balance from 2000-01 to 2021-22 as a per cent of GDP.

The red bars are the latest projections as outlined in the updated MYEFO.

The government is now forecasting a fiscal surplus in 2019-20 of $A4.1 billion (0.2 per cent of GDP) and increasing after that to 0.9 per cent of GDP in 2021-22.

The fiscal shift from one year to another is the change in the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP changes. It is the result of two factors – the fiscal balance itself (in $As) and the value of nominal GDP (in $As).

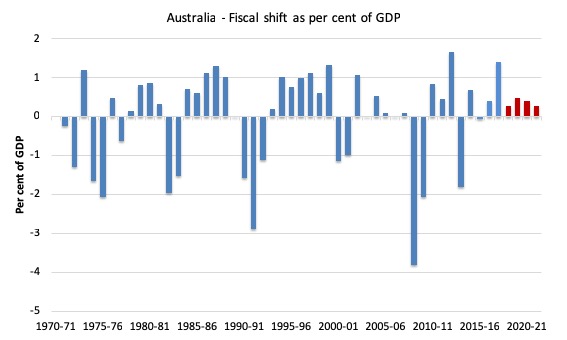

The following graph shows the recent history (from 1970-71) of such fiscal shifts.

The biggest fiscal swing in the previous conservative government’s tenure was in the financial year 1999-2000 (a shift of 1.34 per cent).

A sharp slowdown in the economy followed that contraction and the fiscal balance was in deficit the following year.

The Australian economy only returned to growth because the Communist Chinese government ran large fiscal deficits themselves as part of their urban and regional development strategy. That spurred demand in our mining sector.

The largest fiscal shift in the sample period shown was the second-last fiscal statement from the previous Labor government in 2012-13 which was equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP.

The Labor Treasurer (Wayne Swan) prematurely withdrew the fiscal stimulus bowing to the assault from the neo-liberal press and commentariat about the dangers of deficits. It was a moronic and damaging retreat.

A major slowdown followed and dented the recovery from the GFC that had been spawned by the fiscal stimulus in the previous two years.

That Labor government was obsessively trying to achieve a fiscal surplus in 2013-14 and was blind to the reality that the private domestic sector was not going to fill the spending gap left by the retrenchment in net government spending.

The result – which was totally predictable – the economy took a nosedive, tax revenue fell even further and the fiscal balance moved further into deficit with unemployment rising.

In the MYEFO estimates, the contractionary fiscal shift disclosed for 2017-18 (actual result) is now the second largest since 1970-71 – 1.4 per cent of GDP.

This represents a sharp tightening of fiscal policy which the government is projecting will continue out to the end of its forecast period.

Part of this shift is being driven by the strong company tax payments which are the result of two factors: (a) the end of loss write-off periods for mining companies; and (b) the massive infrastructure spending boom at the State government level, which has boosted activity and employment.

The question is whether this degree of fiscal contraction is warranted.

The answer is a firm no!

How do I determine that:

1. Real GDP growth has slowed dramatically and the annualised September-quarter growth rate is just 1.2 per cent. That is not fast enough to maintain current levels of unemployment.

Please see – Australian national accounts – economy is slowing and looking shaky (December 5, 2018).

2. Wages growth in Australia has been very subdued over the last several years, with real wage gains difficult to achieve.

Wages growth is now at record low levels and real wages started falling in 2017, and in recent quarters have just kept pace with inflation.

There has been a massive redistribution of national income to profits and away from wage-earners as real wages growth continue to lag well behind the growth in labour productivity.

Please read my blog post – Australian workers losing out under neoliberalism (December 10, 2018) – for more discussion on this point.

3. State government infrastructure projects are finite.

4. Labour underutilisation remains high.

The monthly broad underutilisation estimates for October 2018 show that underemployment comprised 8.7 per cent (1,105.5 thousand). The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) was 13.3 per cent. There were a total of 1,777.5 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

The Australian economy is nowhere near full employment.

Please read my blog post – Australian labour market – treading water this month (November 15, 2018) – for more discussion on this point.

5. The ratio of household debt to annualised household disposable income is now at record levels and there are now signs that the demand for credit is in decline.

So household consumption expenditure, which has been propping up growth, will decline as the households exhaust their saving balances.

But the Government’s projections imply that it is intent on driving the private domestic sector into ever more increasing debt levels.

The economic predictions, which underpin the fiscal statement and are contained in Budget Paper No.1 – Economic Outlook, show that the Treasury is forecasting an increasing external deficit over the estimates.

The MYEFO estimates have increased the forecasts from the May statement.

The current account deficit is projected to be 2.75 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 rising to 3.75 per cent of GDP in 2019-20.

The average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2016-17 has been -4 per cent of GDP. So the projections for 2019-20 are approaching the that long-term performance.

So the sectoral balances can tell us what this implies.

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

The sectoral balances equation is:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus the current account balance (CAB) or net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

So (1) is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector to net save (S – I > 0).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to accumulate financial assets.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting.

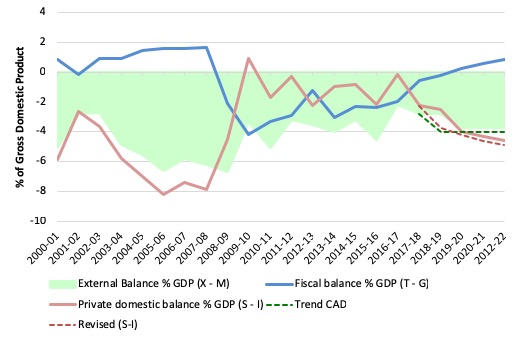

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2021-22, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in the financial outlook.

The vertical black line demarcates the actual from the projected data. The dotted lines just reflect different CAB assumptions (either the Government’s or the long-term trend).

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) more or less projected to be constant over the forward estimates period, the private domestic balance overall (solid red line) is the mirror image of the projected government balance (blue line).

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – that is, in deficit – given the external situation.

This not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to rebalance its precarious debt position somewhat.

You can see the red line moves into surplus or close to it. The long-run average private domestic deficit is 2.4 per cent of GDP and was achieved largely when the household saving ratio was between 10 and 16 per cent and private investment was strong.

The fiscal strategy reaffirmed in the MYEFO yesterday would require the private domestic sector to be accumulating more debt as it progressively spends more than its income to fund consumption growth.

That will probably not happen and the slowing economy will see to it that the fiscal contraction leads to grief.

Taken together, there is a need for a larger fiscal deficit right now and into the future.

But the Labor Party never learns either

The second graph above showed that the record contractionary federal fiscal shift was implemented by a Labor Treasurer (Wayne Swan) in 2012-13, which cut real spending growth by 3.2 per cent of GDP and saw overall spending drop from 24.7 per cent of GDP to 24 per cent in one year.

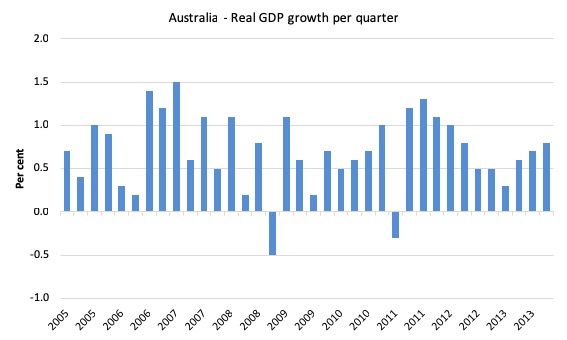

This graph tells you what happened.

Australia had been recovering from the GFC and the fiscal stimulus that Wayne Swan introduced in late 2008 and early 2009 saved the nation from recession.

Apart from a blip in the March-quarter 2011, growth was moving back towards trend and unemployment was falling.

But by 2012-13, the Labor government claimed that a fiscal surplus was of paramount importance despite unemployment and underemployment remaining at elevated levels and household debt remaining at record levels.

The facts are obvious.

They introduced a massive fiscal contraction (reduced the deficit) in one year which killed the movement back to trend growth rates and saw Australian economic growth slide from around 3.2 per cent per annum in the June-quarter 2012 to 1.2 per cent by the March-quarter 2013.

You can relate the real GDP performance to the first graph above, which shows the way the discretionary fiscal stimulus increased the deficit to support that growth.

You can also see the fiscal contraction in 2012-13 failed to sustain a lower fiscal deficit beyond that year.

By killing the growth impetus, the Treasurer stimulated the automatic stabilisers, which, of course, worked against the Treasurer’s intentions.

You would think a person would learn lessons from that.

Now, Wayne Swan is wandering around the nation lecturing us on inequality, the sins of trickle down economics and how his vision for Australia is for a fairer society.

I have seen Tweets lately where he is being used to advocate a “jobs guarantee” as if he some new progressive voice in Australian politics.

It is a pity he didn’t take the opportunity to pursue those sort of things when he was Treasurer.

When the Labor Government was elected in December 2007, the unemployment rate was 4.3 per cent and by the time he left his position as Treasurer it had risen to 5.7 per cent.

The Broad Labour Underutilisation rate in in December 2007, the unemployment rate was 10.4 per cent and by the time he left his position as Treasurer it had risen to 13.2 per cent.

Further, the Gini Coefficients measuring for wealth and income inequalities rose during his time as Treasurer.

And, as I show below, the gap between the unemployment benefit payment and the poverty line continued to climb during his period as Treasurer and his government refused to redress the issue by increasing the unemployment payment because it would damage their surplus ambitions.

So his tenure as Treasurer could only be considered a failure from a progressive perspective.

But, I agree that a person can find a path out of their ignorance to enlightenment through more education, thought and an admission of one’s own failings.

The question is whether Swan has reached that point and whether we should take his current ramblings about employment guarantees and more equitable economic policies seriously..

The evidence is that despite his claims to be concerned about equity etc there is no basic shift in his position. He would do it all again.

He gave a speech at the National Press Club in Canberra on August 21, 2018 – The Global Financial Crisis: 10 Years On – where he reflected on his time as Treasurer during the GFC.

He claimed in that speech that his views on economics had changed such that he now believes that reducing inequality “will give Australia a better economic result.”

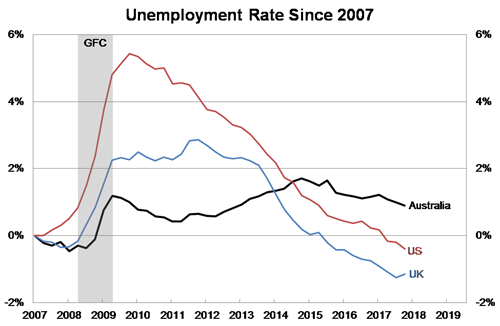

He then produced a graph which I reproduce here – comparing the unemployment shift since 2007 (in percentage points) in Australia, the US and the UK.

Of the graph, he said:

The capital and skills destruction that we avoided in Australia was crucial to locking in higher levels of growth in the years following the crisis, which meant that unemployment was lower, and deficit and debt were lower than if our Labor Government hadn’t acted.

By contrast, the early withdrawal of stimulus in Britain and the inadequacy of stimulus in the United States condemned these countries to a slower recovery and to high levels of capital and skills destruction, which continue to this day.

There is denial writ large here:

1. It is clear that as a result of the fiscal stimulus he introduced as Treasurer, the unemployment rate was moving downward from 2000 to 2011.

2. Then his obsession with achieving a fiscal surplus led to the massive fiscal shift I document above and look what happened.

At the same time as the unemployment rates were falling in the US and the UK, the Australian unemployment rate started to rise again – under his watch.

3. It was all down to his poorly conceived rush to achieve an fiscal surplus, unachievable at the time, given the external situation and the spending plans of the private domestic sector.

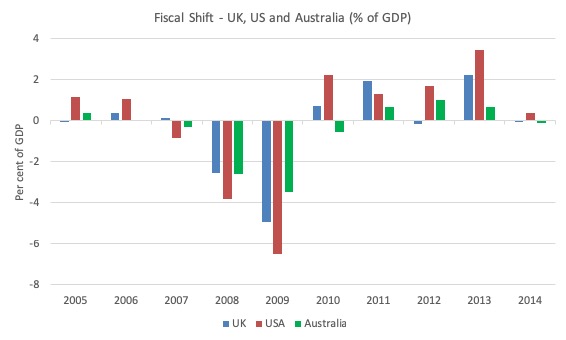

4. The following graph shows the fiscal shifts (explained above) for the UK, US, and Australia from 2000 to 2014. Swan was Treasurer between 2007 and 2013.

The fiscal expansion (sum of discretionary and automatic stabilisers) was higher in the UK and the US in 2008 and 2009.

It is also true that the US and UK shifted to a contractionary stance earlier than Australia.

But by 2011, all governments were contracting their fiscal positions, well before the economies had even remotely recovered from the the GFC downturn.

And by 2014, that strategy had backfired.

And while the growth rate was stronger in the US and the UK and the unemployment rate continued to decline, under Swan’s stewardship, the unemployment rose again and the gains made by the fiscal stimulus were lost.

On March 15, 2017, Swan gave a speech in Adelaide where he discussed the concept of full employment.

He talked about why a future Labour government should adopt the so-called “Buffett rule”, which says that “everyone making over $1m a year pays a minimum effective tax rate of at least 30%”.

Different thresholds have been discussed but this is the ‘tax the rich to pay for services’ trap that many misguided progressives have fallen into.

Wayne Swan claimed that by adopting the rule plus other tax measures, Labour would be able to ‘fund’ more future infrastructure investments.

He told the audience that (Source):

Both sets of measures would go a long way towards repairing our budget bottom line.

And once a person starts talking about ‘budget repair’ and taxing the rich to pay for services you know they have learned nothing from their period as Treasurer.

Same old neoliberal garbage.

So I would not be holding out any faith in Wayne Swan leading the Labour movement (either the unionised or political arm) to any new progressive nirvana.

What you get from him is bluster about equity and job creation couched in all the voodoo stuff about running surpluses and repairing fiscal positions.

Same old.

And don’t expect anything from the current Shadow Treasurer in the Labor opposition – Chris Bowen.

He cannot stop telling everyone that under his Treasurership, a Labor government elected next year will run larger fiscal surpluses.

Idiocy has no bounds on that side of politics.

Refusal to lift the unemployment benefit out of poverty

At the Labor Party Annual Conference in Adelaide this week, a ‘Left-faction’ delegate proposed from the floor of the convention that the unemployment benefit should be increased.

None of the current leadership was willing to go along with such a motion.

The reality is that the Labor Party leadership will only permit another ‘enquiry’ (aka delay the decision hoping the issue will go away) to consider the issue.

The facts are astounding.

I have commented several times on the parlous income support schemes in Australia that have rendered recipients in an increasing state of poverty as a deliberate ploy by government to create a desperate underclass.

We should also never forget that the unemployed (apart from those moving between jobs) are without jobs because the government has chosen not to use its fiscal capacity to cover the spending gap left by non-government spending and saving decisions.

Mass unemployment is always a policy choice by government. It can always ensure there is full employment by offering an unconditional job opportunity to anyone who desires to work but is currently unable to find a job elsewhere.

I have previously considered the state of poverty among the unemployed in these blog posts among others:

1. Why are we so mean to the unemployed? (September 23, 2009).

2. The plight of the unemployed – under growth and decay (November 16, 2010).

3. Our pathological meanness to the unemployed is just bad economics (February 15, 2012).

4. Fat cat bankster wants to make the unemployed even more desperate (August 23, 2012).

5. The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals (April 30, 2013).

6. Framing matters – the unemployed and the farmers (August 7, 2018).

7. ‘Progressive’ groups in Australia captured by neoliberal ideology (September 18, 2018).

The summary of the current state is as follows.

The Newstart Allowance (unemployment benefit) is adjusted every March and September.

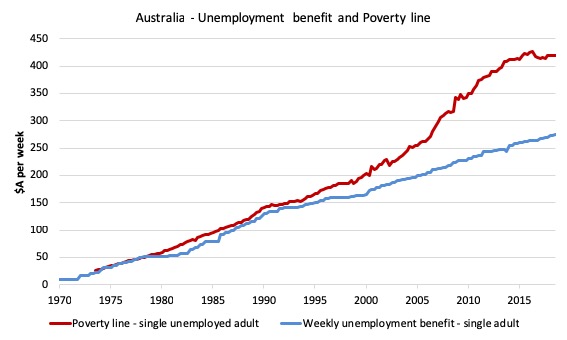

The following graph shows the evolution of the Single Unemployment Benefit and the Single Unemployed Poverty Line since 1973 until September-quarter 2018.

The single unemployment benefit stands at $39.30 per day which is well below any reasonable estimate of the poverty line in Australia (for singles at $A59.89 per day).

For married couples the unemployment benefit is currently at $70.96 per day, while the corresponding poverty line is set at $84.83 per day.

Whether one is single or in a couple, once accommodation is paid for, there is not very much left of the unemployment benefit income.

You can date the widening gap between the unemployment benefit and the poverty line to the early 1980s, when the neoliberal mantra about fiscal surpluses really took hold in Australia.

It was a Labor Party in the 1980s that really cemented the erosion as it started to obsessively pursue fiscal surpluses.

As that narrative gained dominance the gap has widened – both sides of politics have embraced it. The Left sold out in other words.

And now, as they claim to represent the progressive side of politics, they are still arguing that increasing the benefit payment would “cost billions” and jeopardise their fiscal surplus target.

How is that for a party that is meant to represent the workers, the downtrodden and the fragile.

They are an utter disgrace.

The previous Labor government (with Swan as Treasurer) refused to countenance a rise in the benefit payment while they deliberately forced hundreds of thousands to endure prolonged unemployment.

Nothing much has changed.

Conclusion

As I noted in the Introduction, it is a sad state of affairs when a political system is dominated by two neoliberal parties.

And in Australia that is certainly the case, despite the Labor Party stalwarts trying to revise history and claim to be progressives.

Not a lot to look forward to really on that front.

And I hope no-one is beguiled into thinking that the Labor Party, if it gains office next May, will remotely support a Job Guarantee.

Anyone who thinks that they will has no clue about Australian politics and how far the Labor Party has gone down the neoliberal road.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thx Bill

I was only just tweeting to you about the govt surplus craze – thx for this blog.

Keep up the goody fight, I’ll be tweeting and FBing like mad.

Cheers !

Good blog.

‘I’ll be tweeting and FBing like mad.’

What’s FBing? Australian acronym? Sounds a bit rude!

The ALP is a joke.

I’ve taken the liberty of writing them a campaign slogan free of charge.

#f!@kthepoor

Hi Bill, nice article and agree with your sentiments. I too was disappointed with Labor’s announcement (and non-announcements) at their recent Conference re: the unemployed.

One thing, I think we should move away from using terms such as ‘unable to find work’ when speaking of the unemployed as it implies the ‘fault’ of being unemployed lies with the unemployed. It suggests jobs are plentiful and it’s like picking fruit at harvest time. You only need get out of bed, go look for a job and you will find.

It also ignores the two-way nature of the ‘job transaction’, (1) the unemployed applying for a job and (2) the employer offering a job. Most unemployed regularly ‘find’ work they can do, or at least advertisements of jobs they can do, but upon applying are simply not offered the job. There are many reasons for this, not the least there are more people who want to work than jobs available. Clearly this equation is not the fault of the unemployed, and many unemployed are very active at the ‘looking’ and ‘finding’ parts, they are just not receiving offers.

To me ‘finding work’ is an antiquated term, a hangover from a bygone time when jobs where ‘plentiful’ and pretty much the only ‘qualification’ needed was to be a ‘good bloke’ (or person) who needs work.

Regards

Bill! Great work as always. But I’m still waiting for your more detailed Brexit follow-up. Particularly in relation to no deal. It seems today the EU have become worried that preparations have stepped up. Should Britons be worried?

I read an analysis from a conservative economist a few days ago expressing amazement about how our Labour Green government in NZ is currently forecast to spend a lower % of gdp on average than any of the previous 4 governments – National governments included. The economist concluded that retiring debt and being seen to be fiscally austere is more important to this “progressive” government than improving public services or making in roads on improving our welfare system. He found that very odd, whilst supporting the idea of less state involvement in the economy.

I find this very distressing when I see the suffering around me in the poor end of my town.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Looks from your description of the Australian political choices on offer, Bill, that they represent a classic case of the “cartelized party system” described in Blyth and Hopkin here:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/government-and-opposition/article/global-economics-of-european-populism-growth-regimes-and-party-system-change-in-europe-the-government-and-oppositionleonard-schapiro-lecture-2017/32CECBB2EB9F6D707564D5A7944FAB04/core-reader

If their thesis is correct, some form of populism (either of the right or left — I don’t know enough about the prevailing Australian political winds to hazard a guess) may soon emerge.

From the first graph unemployment started to go up when we started running deficit budgets. Unemployment went from 8% to 4% when we were running surplus budgets

Dear Neil (at 2018/12/19 at 3:07 pm)

Yes, there are two ways that fiscal balances and unemployment interact and you need to separate them to understand the causality involved.

1. When aggregate spending is declining and policy settings are unchanged, the drop in economic activity will see tax revenue fall (less employment, sales etc) and welfare payments rise – and the fiscal deficit will rise (or a surplus will fall).

This is why fiscal deficits rise during recessions even if the government does nothing.

And the rogues who try to vilify the use of discretionary fiscal policy shout out – see, the government has increased the deficit and look what has happened – unemployment has risen.

Of course the causality is running from rising unemployment to rising deficit, not the other way around.

2. If the government decides to take discretionary action to stimulate the economy by deliberately increasing spending and/or cutting taxes, you will see economic activity rise, unemployment fall and the fiscal deficit increase.

The causality is running from rising deficit to falling unemployment.

In a typical cycle, the two may interact. So early in a downturn, causality (1) is operating and the government may introduce a stimulus which takes a little time to impact and generate causality (2).

For those unversed in separating the two impacts, the causality can easily become blurred and poor interpretations made.

We must always be sure to understand what is actually happening.

I hope that helps.

best wishes

bill

Hi Mark and others

GetUp! recently posted this article in The Conversation and criticized the pursuit of fiscal surpluses:

MYEFO rips A$130 million per year from research funding despite budget surplus

With a budget surplus in sight, it makes no sense to cut funding from Australia’s research capacity.

I wrote the following comment:

Dear Chris Bowen (you should be reading these GetUp! comments threads assiduously),

I am concerned that you and Bill Shorten have hemmed yourselves in with meaningless and inappropriate commitments to “get back to surplus.” The consequence will be that you will inflict on Australia increased private sector indebtedness with all the attendant financial fragility and negative impacts for living standards. You will disappoint the voters almost from the very beginning and you will limp your way to two terms at the very most.

It is extremely silly for the government to set a fiscal surplus as a target under current economic conditions.

A fiscal surplus just means that in a given financial year the government deleted more dollars of private sector financial wealth than it added.

That is all it means.

The government cannot stockpile, hoard, or accumulate its own currency that it spends into existence thousands of times daily by keystroking numbers into Exchange Settlement Accounts at the Reserve Bank of Australia.

It would only be appropriate for the federal government to run a fiscal surplus if the domestic private sector and the external sector were spending like crazy. Then the government would need to net delete enough non-government sector Australian dollar financial wealth to contain inflation.

We do not face that situation today. We have a small trade account surplus and we have an income account deficit that outweighs our trade account surplus. This means that overall we have a current account deficit. The external sector is a spending or demand leakage for the Australian economy.

In addition to that, the domestic private sector wants to net save. It wants to spend less than it earns. This is another spending or demand leakage from the Australian economy.

In order to offset those demand leakages, and provide enough income for the non government sector to meet its tax obligations and achieve its desires to spend, save, and do paid work, the federal government should really be running a larger deficit than it is today.

700,000 unemployed.

1.1 million under-employed.

200,000 discouraged job-seekers (at least).

On top of that, there are buildings, factories, and equipment that are not being used to their full potential.

There is a vast amount of unused productive capacity in the Australian economy.

The correct fiscal stance for the government under these circumstances is expansion, not contraction.

The extra spending needs to be targeted wisely on activities that are socially useful and environmentally healthy.

Ensuring that everyone who wants interesting and meaningful and decently paid work has their wishes met should be a high priority.

Making our public infrastructure and public services first class should be a major goal.

We must decarbonize our economy completely and enact comprehensive, generous measures of support and transition for the people whose livelihoods and communities are affected by this change.

Targeting a particular fiscal outcome is the wrong way to go about designing economic policy.

The government must pursue real world outcomes that meet the needs of our people and enhance the natural ecosystems to which we belong.

The fiscal balance is largely a non-discretionary variable anyway. The government does not control the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector. It makes no sense to target a particular fiscal balance. It’s an ex post variable whose number we know after the event.

Economically illiterate people use terms like budget repair, the national credit card, running out of money etc. when discussing the federal government.

It is important that people understand that the federal government’s financial position is nothing like that of a household or a business or a state or local government.

Please consider talking honestly and accurately with the voters about the financial capacity of the Commonwealth Government. The government is constrained by the availability of real goods and services that are for sale in the government’s currency. There is no financial constraint on the federal government’s capacity to make payments in its own currency.

It will be far better for a Shorten-Bowen Government and far better for the Australian people if you win a mandate for economically literate policies.

Please don’t disappoint us again. We need you to succeed. Success in government depends on accurate communication with the public while you are still in Opposition. Don’t wait until you are in government before you embark on the educative task of explaining what money is and how government spending works.

Best wishes

Nicholas

——–

Then a Labor support posted this reply to my comment:

I for one don’t think Labor disappointed last time in.

I also think they spent the money they had wisely.

Here is a small list of what Labor achieved last time around, and a few things that didn’t quite get done, but showed through those policies Labors ideology, to create legislation policies for a better Australia.

I was impressed with your thought provoking post Nicholas, and will take it to the Labor executive, I hope if you were disappointed by Labor last time around for any reason, 2019 onwards makes up for it.

——

Perhaps it would be helpful if you respond warmly to this man’s constructive offer to take our concerns to the ALP national executive. I am under no illusions about the likelihood of anything concrete emerging from this but I find it helpful to engage with anyone who is open to thinking differently about the nature of federal government finance.

I should clarify that GetUp! posted the link on Facebook and my comment and the Labor fellow’s comment are in that Facebook thread. I can’t post the link but if you search GetUp’s Facebook page you’ll find that they posted it on Tuesday 18th December 2018.

From an economic policy perspective the ALP is still wedded to a flawed quasi Paul Krugman/Richard Holden approach to Macroeconomics, which is still strongly based within neoclassical economics. I believe there are a small number within the ALP who have a basic understanding of MMT, but are frightened to look at macroeconomic reality because the economic commentariat, the financial sector gurus and the treasury/reserve bank boffins continue to propagate the neoclassical narrative ad nauseam. They want to be seen as conforming to the mistaken but “conventional economic view” for electoral success. Their reasoning and those of their leaders is lets not frighten the horses in any way, shape or form, i.e. meaning basically lets not upset some of our political donors before a major election. They also see the media backlash against constructing any new economic policies that contradict the “conventional view” as politically dangerous and therefore not realpolitik.

Until we get a critical mass of people educated in new macroeconomics/microeconomics in the unis, unions and the community at large, political parties like the ALP will continue to spew out neo-liberal light economic policies that will be devastating for Australia. We need a revolution in the teaching of Economics, so lets work together to establish new economic education across the community. A MMT university would be a good start!