It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

Must be Brexit – UK GDP growth now outstrips major EU economies

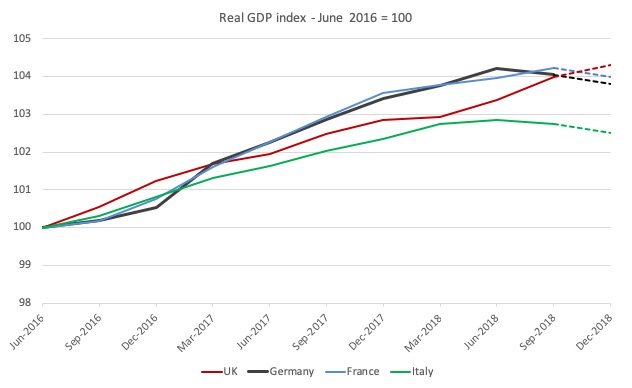

I suppose Brexit is to blame for the fact that Britain is now growing faster than the major European economies. The latest ‘monthly’ GDP figures show that the British economy grew by 0.3 per cent in the three months to November 2018 and will probably sustain that rate of growth for the entire final quarter of 2018. This is in contradistinction to major European economies such as Germany (which will probably record a technical recession – two consecutive quarters of negative growth) with France and Italy probably following in Germany’s wake. I have made the point before that the growth trajectory of the British economy (inasmuch as there is one) is very unbalanced and reliant on households and firms maintaining expenditure by running down savings and accessing credit – which means ever increasing private debt burdens. With private credit growth weakening as the debt levels become excessive and the rundown of saving balances being finite, Britain will face recession unless the fiscal austerity is reversed. Earlier in 2018, the Guardian Brexit Watch ‘experts’ were continually pointing out that Britain’s growth rate was at the bottom of the G7 as evidence that Brexit was causing so much damage. So now European G7 nations are starting to lag behind, these commentators will have to find another ruse to pin their anti-Brexit narrative on. We also consider in this blog post some more Brexit-related arguments – pro and con – which reinforce my conclusion that a No Deal Brexit will not cause the skies to fall in.

One of the sources of impatience if one likes to see data trends is that fact that quarterly national accounts data is three months old by the time it is made available by the central statistical agencies.

The British Office of National Statistics has alleviated some of that dissonance by introducing monthly estimates of GDP, which has been the result of a process “to improve the trade-off between the timeliness and accuracy of early estimates, resulting in fewer revisions.”

On April 28, 2018, the ONS published an article – Introducing a new publication model for GDP – which came into operation in July 2018.

They informed data users that:

In summary, this model will give two (rather than three) estimates of quarterly GDP, and speed up the Index of Services publication by two weeks, enabling the publication of monthly GDP estimates.

You can explore the above link if you are curious about the detail.

On January 11, 2019, the ONS published the – GDP monthly estimate, UK: November 2018 – which showed that:

1. “UK gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 0.3% in the three months to November 2018”.

2. The rolling three month growth rate has been in decline since the third-quarter 2018 result of 0.6 per cent was published.

3. “Manufacturing saw a steep decline, with car production and the often-erratic pharmaceutical industry both performing poorly.”

4. “The services sector was the largest contributor to growth, at 0.24 percentage points”.

5. “The construction sector also had a positive contribution, with rolling three-month growth of 2.1%. However, growth of negative 0.8% in the production sector acted as a drag on GDP growth”.

6. “Monthly gross domestic product (GDP) growth was 0.2% in November 2018, following flat growth in September 2018 and growth of 0.1% in October 2018.”

I have made the point before that the growth trajectory of the British economy (inasmuch as there is one) is very unbalanced.

Real household disposable income growth is flat and there has been a substantial and sustained fiscal contraction over the last several years while the nation has been running a continuous external deficit.

Under those circumstances, the only way any growth can occur is via increased private domestic sector deficits, which is what the data over a long period of time has been telling us is that has happened.

Growth is thus reliant on households and firms maintaining expenditure by running down savings and accessing credit – which means ever increasing private debt burdens.

We are seeing credit growth weaken as the debt levels become excessive. And the rundown of saving balances is finite.

Sustaining growth through ever-increasing private domestic debt is not a sustainable process and eventually the balance sheets of the private domestic sector borrowers become so precarious that they put the brakes on and that means spending growth slows.

At present, Britain is producing the pre-conditions for another balance sheet recession and that will occur if the British government continues to undermine growth with its contractionary fiscal policy.

My most recent analysis on this issue was in this blog post – The Brexit scapegoat (January 7, 2019).

The UK Guardian economics writer Larry Elliot makes the same point in his recent article (January 11, 2019) – Beneath the bonnet of the UK economy, there are plenty of faults.

Larry Elliot notes that:

Judged by what is happening in the rest of Europe, Britain’s economic performance in late 2018 was reasonably good … The UK is likely to have grown by 0.3% in the final three months of 2018, and by contrast with the other major European economies that’s not too shabby.

But:

The real problem is that growth is both modest and unbalanced. Manufacturing is struggling … The trade deficit is widening … Such growth as there is is heavily reliant on the willingness of consumers to spend.

Here is some context.

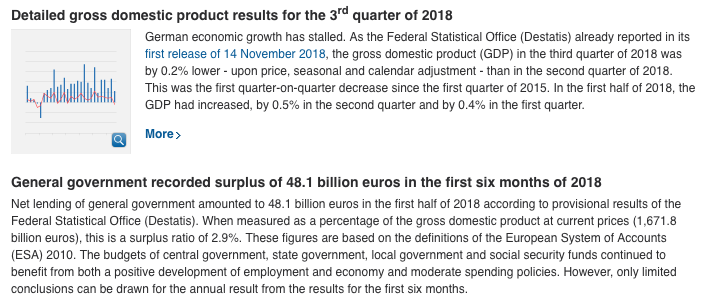

On November 11, 2018, Eurostat released its latest GDP figures for the Eurozone – GDP up by 0.2% in the euro area and by 0.3% the EU28, which showed that:

1. Eurozone GDP growth had fallen by half in the third-quarter from 0.4 per cent to 0.2 per cent, which a market downward trend emerging. This was the lowest growth in the Eurozone for four years.

2. EU28 growth had also fallen from 0.5 per cent to 0.3 per cent in the third-quarter.

3. Real GDP growth has been trending down since the third-quarter 2016.

4. Germany contracted by 0.2 per cent in the third quarter and the trend is downwards.

5. Italy recorded zero growth (trending downwards).

6. France recorded 0.4 per cent but will definitely slow in the fourth quarter after all the civil unrest that has now overtaken the nation.

7. The UK recorded a solid 0.6 per cent growth rate up from 0.4 per cent in the June-quarter.

So it was clear that despite all the headlines in British newspapers about the damage Brexit was causing, Britain was emerging as one of the better performers of the large European economies.

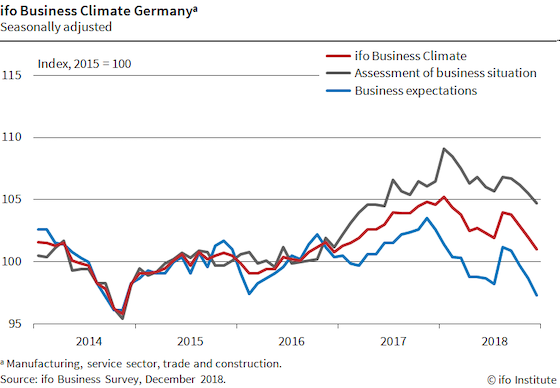

For Germany, the Ifo Business Climate Index, which is a highly credible indicator of the state of the German economy was last published data for December 2018.

We read in the – December edition – that:

1. “Concern is growing among German businesses”.

2. “Companies were less satisfied with their current business situation. Their business expectations also continued to deteriorate. The German economy faces a lean festive season.”

3. “In manufacturing the business climate index fell markedly … manufacturers scaled back their production plans.”

4. “In the service sector, the business climate deteriorated considerably.”

Here is a time-series chart showing the contraction in business climate in Germany.

A reasonable expectation is that the Eurozone will have a high chance of recording negative growth in the fourth-quarter 2018, with Germany recording its second consecutive negative GDP quarter – that is, going into official recession.

I took this snapshot from the National Accounts page of Statistiches Bundesamt (De Statis), the German national statistical agency, which announced the third-quarter 2018 results.

The juxtaposition is very telling.

Italy and France will probably be following, not far behind.

The French statistical agency, INSEE (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques) reported that for the third quarter (Source):

After weakening since the beginning of 2018, the French business climate has stopped declining …

However, that data was compiled before the chaos that has now descended on France. I would be highly surprised if the INSEE indicator does not turn down sharply in the fourth-quarter.

The following graph shows the evolution of real GDP in the UK, Germany, France, and Italy from June-quarter 2016 to the September-quarter 2018. The dotted lines are a reasonable projection for the fourth-quarter.

We already know that for the three months to November 2018, Britain grew by 0.3 per cent.

If the so-called ‘rising Brexit anxiety’ is so damaging why is Britain outstripping the other large EU economies?

Earlier in 2018, the Guardian Brexit Watch ‘experts’ were continually pointing out that Britain’s growth rate was at the bottom of the G7 as evidence that Brexit was causing so much damage.

It was at a time when the weather was playing havoc with British production.

The ONS acknowledges this impact:

Rolling three-month growth was 0.3% in November 2018, continuing the return to moderate growth rates after some volatility earlier in the year, in part related to the weather.

So now European G7 nations are starting to lag behind, these commentators will have to find another ruse to pin their anti-Brexit narrative on.

And this brings me to two points which have been illustrated in material published by those on the Remain side and those on the Leave side.

I read an interesting book recently – It’s Quite OK to Walk Away – which was written by Michael Burrage and published by Civitas in April 2017.

The author is “a director of Cimigo, which is based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and conducts market and corporate strategy research in China, India and 12 countries in the Asia Pacific region.”

So he is not part of what we might think of being the British ‘bubble’ although he has contributed some excellent, evidence-based inputs into the debate about the value of the EU.

One report from July 2015 – A club of high and severe unemployment: the single market over the 21 years 1993-2013 – is a good account of the poor performance of the Single Market, which is at the heart of EU neoliberalism and which many of the Europhile Left fawn over as being essential for the future of Britain.

He concluded in that report that:

In 18 of these 21 years, EU unemployment has been more than double that of these three countries, and in the other three years, 2004-6, it has been only fractionally less than double. This comparison does not therefore support the idea that there is a peculiarly European high unemployment profile. On the contrary, it suggests that high unemployment is a distinctive and enduring EU characteristic, not a European one.

He also shows that long-term unemployment has not just been a problem after the GFC. For example:

While recent rates of long-term youth unemployment are astonishingly high, they were almost as high in some countries over the first decade of the single market. Unnoticed by the UK media, well over half of young, Italian men and women were unemployed for more than a year over the 11 years from 1993-2003, as were over half of young Greeks over the five years from 1996-2000. More than a third of young people in several other EU countries, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, had a similar experience, and even, surprisingly, though for fewer years, Belgium and the Netherlands.

And his conclusion?:

The problem of unemployment is often mentioned in statements of presidents of the European Commission, and occasionally in the European Council and the European Parliament, but it is difficult to avoid the feeling that it has come over the past two decades to be accepted as a normal, non-political and therefore settled part of life within the EU. Its persistence is a rather good illustration of the limitations of the political process within the EU. It is difficult to think of a more serious social problem, blighting the lives of millions, and yet it has not generated any impassioned, partisan debates about the causes or solutions of it, or rival claims about which particular European leader or party best speaks on behalf of those who have suffered from it.

As a result of reading that analysis some years ago I was thus interested to see what Michael Burrage would write about a No Deal Brexit.

There is a lot to commend in his It’s Quite OK to Walk Away book.

However, one has to be careful not to fall into the ‘growth rate’ trap and ignore levels.

In one exercise, Michael Burrage ranks “the top 40 fastest growing significant exporters of goods to the EU founder members of the Single Market and found that, if placed amongst them, the UK would have finished in 36th position”.

Note this is not the top exporters but the nations which have recorded the fastest growth in their exports to the EU.

The table he presents shows that:

1. “non-members have access to the Single Market”.

2. “membership does not ensure a higher rate of growth of exports to the Single Market than non-members”.

3. “The UK’s exports are the third largest in value, but in terms of growth it has not done well over the past 23 years, as the earlier extrapolation suggested, and lies in 36th position.”

He acknowledges that one might conclude that the UKs growth is “low because the value of its exports is so large” and that some “countries are bound to have high rates of growth because they start from next to nothing”.

But in the period prior to the Single Market (the “Common Market decades”), he shows that “the UK was not only the largest exporter to the EU, but also grew faster than many of the other large exporters of the era”.

4. “Export growth, we may safely conclude, has not been one of the benefits of the Single Market for the UK. Countries exporting under WTO rules, like the US, do not appear to be at any great disadvantage.”

Interestingly, Australia achieves higher export growth rates into the EU than the UK, which suggests that there is more to export access than the ‘gravity models’ (near is good) so loved by the Remainers would like one to believe

In Chapter 13, he similarly ranks the nations “with regard to services exports”.

He concluded that:

The UK has therefore enjoyed rather more success, in terms of the growth of its services exports to other members than of its goods, finishing in 25th place, and the EU 28 finished just above it in 24th.

So what can this sort of analysis tell us?

First, Michael Burrage concludes that:

… it casts serious doubt on the notion that the single market in services has promoted rapid growth of services exports amongst its members while putting non-members at a disadvantage …

… the single market in services has not promoted more rapid growth of services exports amongst its members, nor put non- members at any noticeable disadvantage, it is difficult to see what the UK will lose by withdrawing from it, or why anyone should be in the least distressed that it has decided to do so.

Overall, it is clear that nations trading under WTO rules have experienced significant growth in exports to the EU since the Single Market was launched although the domination of China skews these figures upwards.

This is not to say that the EU has become a more important trade market for these non-EU Member States. In fact, exports to the EU as a proportion of total exports among the nations trading with the EU under WTO-rules has fallen slightly since the inception of the Single Market.

But that is because other trade destinations have grown more quickly than the EU markets and doesn’t alter the fact that nations trading under WTO-rules have increased their access to the EU markets since the Single Market was formed.

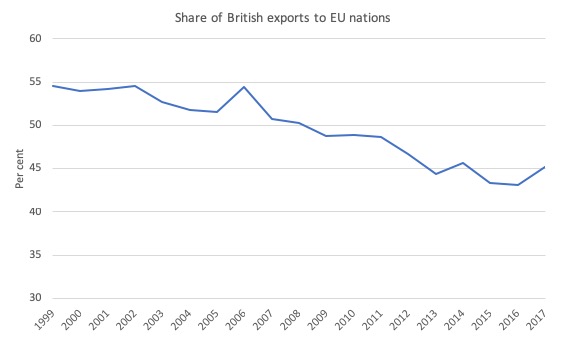

Further, while some might argue that it is not the growth rate that matters but the share, the fact is that the UK has been diversifying its exports away from the EU.

This graph shows the share of UK exports that go to other EU countries from 1999 to 2017.

In 1999, the EU share of British exports was 54.6 per cent.

By 2017, the proportion was just 45.2 per cent.

While the value of exports to other EU nations has risen from £133,342 million in 1999 to £278,944 million (109 per cent), total exports have risen by 152.8 per cent over the period.

Thus the share has fallen because Britain has increased its total exports to other non-EU nations.

The point is that the EU markets have been a declining relative factor for British exporters long before the notion of Brexit emerged.

On the other side of the debate was a truly poor article by one Tom Kibasi (December 5, 2018) – Embracing Brexit would be a historic mistake for the left – who appears to have zero faith in the capacity of the Left to organise political action.

He wants a second referendum on Brexit and then he would want a third referendum when the second delivers the same outcome as the first and so on.

He thinks the EU is the best thing going despite listing a litany of atrocities that have occurred within the EU because of the way the EU operates.

He falls into the standard traps:

1. He claims that the EU is not neoliberal because the state still spends lots – I will come back to that.

2. He claims that it takes time to make meaningful reforms – this is the usual Europhile Left claim – meanwhile a generation of young Europeans are being alienated and excluded while the ‘tinkering’ goes on without any meaningful progressive reform.

3. He claims that prohibiting state aid is desirable if you want free trade which he thinks is good for businesses.

He thus eschews the state being able to have a sensible regional development framework based on state support.

In his 2007 book – The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (London, Bloomsbury Press), Ha-Joon Chang wrote that:

This neo-liberal establishment would have us believe that, during its miracle years between the 1960s and the 1980s, Korea pursued a neo-liberal economic development strategy …

The reality, however, was very different indeed. What Korea actually did during these decades was to nurture certain new industries, selected by the government in consultation with the private sector, through tariff protection, subsidies and other forms of government support (e.g., overseas marketing information services provided by the state export agency) until they ‘grew up’ enough to withstand international competition. The government owned all the banks, so it could direct the life blood of business-credit …

The Korean government also had absolute control over scarce foreign ex- change (violation of foreign exchange controls could be punished with the death penalty). When combined with a carefully designed list of priorities in the use of foreign exchange, it ensured that hard-earned foreign currencies were used for importing vital machinery and industrial inputs. The Korean government heavily controlled foreign investment as well, welcoming it with open arms in certain sectors while shutting it out completely in others, according to the evolving national development plan …

The popular impression of Korea as a free-trade economy was created by its export success. But export success does not require free trade, as Japan and China have also shown. Korean exports in the earlier period – things like simple garments and cheap electronics – were all means to earn the hard currencies needed to pay for the advanced technologies and expensive machines that were necessary for the new, more difficult industries, which were protected through tariffs and subsidies. At the same time, tariff protection and subsidies were not there to shield industries from international competition forever, but to give them the time to absorb new technologies and establish new organizational capabilities until they could compete in the world market.

The Korean economic miracle was the result of a clever and pragmatic mixture of market incentives and state direction.

Indeed, the normal model of economic development, which has enriched the advanced nations such as Britain and the US, was not built on a ‘free trade’ platform – the IMF/World Bank ideology.

Rather, they developed into rich nations through the use of industrial protection and government controls and supports.

None of the advanced nations would have achieved that status if they followed the IMF/World Bank approach.

So it is hard to justify the ‘race-to-the-bottom’ model, where workers in poor nations are paid poverty-level wages and work in appaling and dangerous conditions (including a return to C18th child labour), while regions in developed nations are hollowed out with entrenched unemployment and increasing poverty and social alienation.

I covered these issues in this suite of blog posts:

1. The case against free trade – Part 1 (October 27, 2016).

2. The case against free trade – Part 2 (November 8, 2016).

3. The case against free trade – Part 2 (November 22, 2016).

State aid is an essential part of this development strategy.

4. He claims that nationalisation is possible under EU rules because the Treaties “no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership”.

It is true that public ownership is possible within the EU although the ‘direction’ of intent is to dilute it as far as possible.

This recent article (January 10, 2019) in the Railway Gazette – France to tender operation of two inter-city routes – indicates what pressures the EU is putting France under to open up its publicly-owned railway system to private competition.

What will amount to a privatisation of railway services in France is:

… intended to ensure that France complies with the provisions of the EU’s Fourth Railway Package.

Moreover, the tendering process follows the renewal of the state of “the rolling stock”.

And “Future tendering of other state-managed TET services would only take place once fleet and infrastructure enhancements have been completed ‘over the coming years’.”

So state subsidies for private profit. That is the EU version of a ‘free market’.

Moreover, what is not possible under EU law is for a Member State to renationalise an already privatised activity (say, the rail system) and create a publicly-owned monopoly, which is exactly what British Labour are proposing in their Manifesto.

But the point of this blog post is not to critique those arguments. They have been done to death and found wanting.

The point is that Tom Kibasi uses data to make the claim that “anyone who thinks the EU prevents the state from having a role in the economy ought to meet Denmark, Finland and France.”

This is a classic Europhile Left argument but just creates a straw person.

The informed Left who favour the demolition of the EU (I belong in this group!) have never said the EU “prevents the state from having a role in the economy”.

Indeed, the thesis in our book Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017) – is predicated on the state being the vehicle through which neoliberal policies are organised and imposed.

Think about Greece. The Socialist party in government is the facilitator of the worst excesses of neoliberalism.

To support his case, Tom Kibasi writes:

In each of these countries …[France, Finland, Denmark] … according to OECD data, government spending was 55 per cent or more of national income. That means more of the economy was in the government sector than the state sector. This Conservative government’s plans are for government spending to be 38 per cent of national income in the 2020s.

In other words, he is trying to say that because government spending is still significant there has been no retrenchment of state activity.

Think about Greece again – the general government sector spending in 2015 (according to latest OECD data) was 53.5 per cent of GDP. Hardly a verification of a neoliberal free-zone.

But a meagre statement of levels doesn’t tell us anything about dynamics. The accusation is not that the EU has always been neoliberal in its intent.

The accusation is that the EU embraced the burgeoning neoliberal ideology and entrenched it within its structure – the Treaties, the Single Market framework etc.

So we are looking at the change in data not the level.

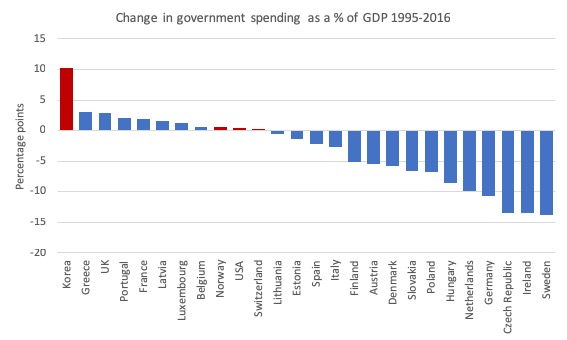

Consider the following graph compiled from the OECD data that Tom Kibasi cites – General Government Spending – and which shows the percentage point change in the proportion of government spending in the economy (GDP) from 1995 to 2016 (latest data).

The red colums are non-EU nations (within the OECD). Some nations (mostly non-EU are excluded because the data was not complete). These exclusions further strengthen the conclusion.

This graph gives us some idea of the changing landscape in the EU after the Maastricht process was agreed.

The bias is clearly neoliberal – to reduce the relative proportion of government spending – despite the period being marked by a massive intervening crisis.

So just quoting levels ignores the direction of change.

The last issue I have been exploring is the concept of the Single Market in services, which has received a lot of attention in the British debate, given the position of the financial sector.

For example, on March 8, 2018, the Conversation article – Brexit: why Britain’s hopes for a special financial services deal are set to be dashed – said:

The City is the home of the financial services industry which makes up 10% of the UK economy and is one of the few areas that the UK has a trade surplus with the EU. Hammond wants to ensure both the continuation of business with Europe and preserve those attributes that made the City a global centre for finance …

By losing its place in the single market, London can no longer guarantee access to the world’s biggest consumer market of nearly 500m people.

The question Michael Burrage poses is:

Is it possible that all these well-informed and powerful persons have been talking about something that does not exist? Impolite or not, one must persist with the question, because by some measures its existence is in doubt, and one would not want those distressed by Mrs May’s decision to withdraw from the Single Market to waste their grief on something that does not exist.

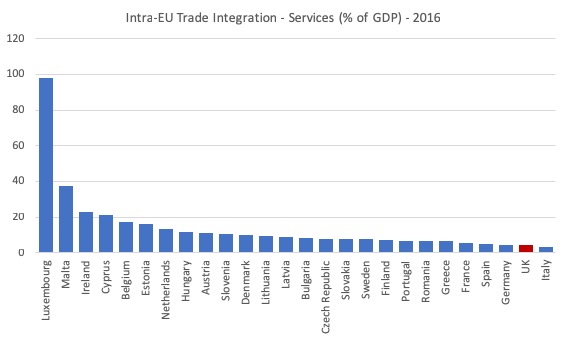

The EU publishes on its Single Market Scoreboard – page measures of the overall importance of trade in goods and services for EU members.

One measure of the extent to which each Member State is involved in the EU is the Intra-EU Trade Integration as a per cent of each Member State’s GDP.

The last data was published for 2016. I excluded Poland because the data for services is missing.

The following graphs rank the data by Member State from highest to lowest for goods and services individually.

Two conclusions:

1. The UK is not very ‘European’ by these measures. Intra-EU trade in goods accounted for 9.7 per cent of GDP in 2016 and 4.2 per cent for services.

2. The claim that there is, indeed, a ‘single market’ for services is not established in the data. Services are still largely provided on a national basis even though the narrative from the Remain camp would have one believe there is a massive single market out there.

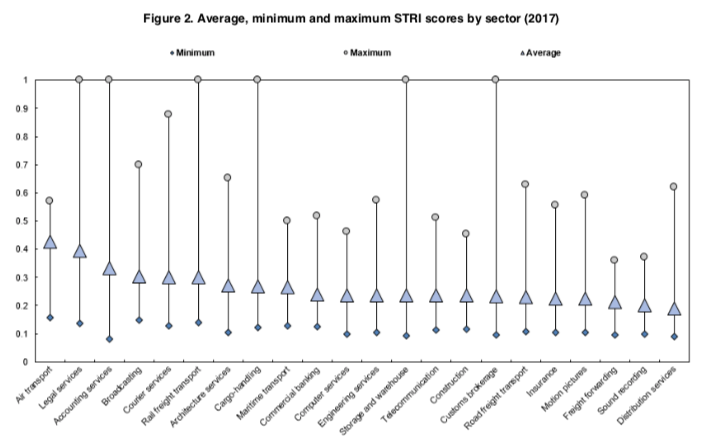

Further, the Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) published by the OECD “provides an up-to-date snapshot of services trade barriers in 22 sectors across 44 countries, representing over 80% of global services trade.”

The following graphic is taken from the latest – STRI policy note updated with 2017 data (March 2018) and shows the disparity between the OECD Member States.

By way of interpretation, a value of zero indicates “complete openness to trade and investment” and a value of one indicates “total market closure to foreign services providers”.

The graph shows average levels and extremes values for each of the services sectors in the STRI.

The large divergences in export access to service sectors between the Member States tells us that there is not an effective ‘single market’ in services.

Conclusion

None of this discussion should be taken to say that the period following Brexit will not be disruptive and in some cases (sectors) majorly so as adjustments to the new environment ensue.

But what it suggests is that major arguments put forward by the Remain camp are not evidence-based.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

In Germany, the populist rightists of the AfD have inserted “Dexit” (Germany leaving the EU) into the political debate. If the idea was unsavory to most Germans already, having it associated with this party will, in my opinion, must surely bury it. Ironically, the reason they want to leave the Union is because they (correctly) identify Brussels as a tyrannical master undermining the european national governments sovereignity, but either fail to see or choose to ignore the fact that Brussels acts mostly at the behest of the German delegation and don’t seem to have a problem with the austerity imposed on the other nations. That is without going into their economic platform that makes the (neo-)liberals at the FDP look like Marx on steroids.

However, were they to succeed in their effort and banking on the dutch lacking the necessary political power to stay the course of the Eurogroup, wouldn’t Germany leaving the Union (and most importantly the currency union) actually be positive for most of the other members? I would expect a new German currency to soar in value thus making German imports more expensive and maybe free some room for local industries and commerce to regain traction across Europe. However, the heavily export oriented German economy could take a nosedive and pour gasoline in an already hostile political environment.

I know Krugman posted a thought experiment on Germany leaving the currency union, but I’d be interested to hear Bill’s or some other MMT’s opinion on this matter. I have browsed Bill’s blog but haven’t found anything on it (probably becasue it’s more than unlikely). Any links would be welcome.

Cheers!

Hermann, do you mind my asking which country you are living in now? Apologies if you consider this too personal, but you have alluded to this in the past. We have to distinguish leaving the Eurozone and leaving the EU. I am not saying you fail to make this distinction, but so many do. From what I can discern, Germany is unlikely to leave the Euro because, so far, it is benefitting Germany. This situation can’t last forever, as it is unsustainable, but I would not be surprised if they push their position as much as then can as long as they can. i don’t know whether you agree.

Bill:- “Indeed, the normal model of economic development, which has enriched the advanced nations such as Britain and the US, was not built on a ‘free trade’ platform – the IMF/World Bank ideology. Rather, they developed into rich nations through the use of industrial protection and government controls and supports”.

I don’t think it’s historically accurate to yoke Britain together with the US (or France, Germany, et al) in the particular respect being cited.

The key distinguishing feature of Britain’s 19th-century trade policy after the repeal of the Corn Laws (ie the repudiation of protectionism, which had served the landed interests) was in fact its focus – obsessive at times – upon free trade. Bright and Cobden were its principle ideological apostles and they attracted overwhelming support. Britain’s policy (especially in regard to agriculture) contrasted starkly with that of its major western trading rivals of the time (continental European, Germany in particular after 1871, and the US), which was – as Bill says – closely analogous to that pursued in our own day by South Korea, for somewhat analogous geopolitical reasons.

However I’d readily concede that that’s largely peripheral to the main thrust of Bill’s argument pertaining to today’s world in general, and Brexit in particular, and therefore doesn’t detract in the least from its (even by his own high standards, formidable) cogency.

Awaiting (as I write) with trepidation the outcome (or absence of any) of tomorrow’s fateful Commons vote on Teresa May’s “deal”, I for one am filled with foreboding.

The events of the past 31 months-long shenanigans do not augur well for coherence either in the debate or in the voting. If it runs true to form it will be chaotic, while the likelihood of that vanishingly rare commodity common sense playing any part (let alone a decisive one) is nil.

By “common sense” what I mean is the position taken by (among others) Michael Burrage – as quoted – and by Bill himself. Shining examples both.

But note that both write from a perspective external (physically as well as emotionally) removed from the intellectual cockpit which is British politics. To hope let alone expect that common sense can emerge out of that would be sheer blue-eyed naiveté. It won’t – except perhaps by accident.

I also though British live in another (EU as it happens) country. Is it perhaps an indispensable requirement for maintaining any vestige of sane, sober, rationality about Brexit that one not actually *reside* in Britain?

And (equally) that to acquire any realistic appreciation of the true nature of what the EU has turned-into while actually living in it necessitates that one not be a citizen of any member-state?

What a sad state we are all in, if so.

Apropos of Kibasi’s preposterous claim that “anyone who thinks the EU prevents the state from having a role in the economy ought to meet Denmark, Finland and France” here are some recent snippets from the Finnish media:-

(quote) The examination of judgments on demand for payment given by district courts provides an idea of Finns’ debt problem. According to Jouni Muhonen, the fact that the number of judgments has increased by almost a fifth (18%) is very alarming. “Consumers applying for new credit have more debts than before. The consumers who applied for new credit from companies exchanging positive data in 2018 typically had other consumer credits in the amount of 6 500 euros. The sum has increased by a third in a year”, says Jouni Muhonen.

In practice, this statistical information confirms the general observation that consumers delay the collapse of their house of cards of debts by paying off old credits with new ones. Examined by age groups, there are two trends in the payment defaults: the situation is improving in the youngest adult age groups, but the trend is the opposite among the seniors. There are now 9 per cent fewer people under 20 years old with payment defaults than a year ago, and among the 20 – 24 year olds, the number has also decreased slightly…

…On the other hand, the number of persons with payment defaults is growing fast in the group of senior citizens. As many as nearly 34 500 over 65 year olds have a payment default entry, and the number has increased by nine per cent in a year. (end of quote)

(keep in mind that the entire population of Finland is barely 5.5 million)

A classic instance of neoliberalism-mandated, state-shrinking, deficit-reduction directly causing mushrooming private indebtedness.

(quote) DRAMATIC CUTS in innovation and technology funding have severely eroded the international competitiveness of Finland, concludes a report drafted by Erkki Ormala, a professor of practice in innovation management at Aalto University. Ormala presented his report on the adequacy of the measures taken by the government to promote applied research to Minister of Economic Affairs Mika Lintilä in Helsinki on Wednesday.

“It’s unfortunately a scientific fact that sustainable economic growth, productivity development and employment are dependent on successful innovation activity,” he stated in a press conference. “The question at hand today is do we want to accelerate economic growth and consequently save the welfare state in Finland? Or do we want to continue on the current track, which will lead to a situation where it’ll no longer be possible for us to maintain the welfare state we’re accustomed to today?” (end of quote)

(Note especially: “the current track”).

Another classic instance of the shrinking of EU member-states’ public sectors (more correctly, of their being systematically shrunk, over decade(s), in obedience to neoliberalism’s dictates).

I hope Bill lets us discuss this. I can’t get replies on other sites.

The question I want to ask is —

How much difference does it make if the US Gov. sells bonds after the fact to pay for deficit spending compared to just creating dollars and spending them? I’m assuming here that there is no crisis, just the normal every day situation.

I will use a game of Monopoly(c) to illustrate my argument. I will make a few rule changes though.

1] At the start each player gets $1000 in cash and five $100 bonds.

2] Each time you go past GO you get $2 in interest for each bond you hold.

3] The Bank or a separate bank will buy your bonds [u]during your turn[/u] for a discount of $1, so you get $99. During your turn it will sell you a bond for $99.

These rules are intended to replace the *fact* that you can sell a US Bond at most any time and there is always going to be a willing buyer for it if there is a small discount. That is, US Gov. Bonds are very liquid. If this is not the case please tell me I’m wrong about this.

Now, I ask you, are these rules going to make any difference in how the game is played?

I assert that they change things very, very little.

Steve American- MMT says that deficit spending with bond issuance has very little real difference from the government just creating and spending the money. You can read the answer to question 2 on this August weekend quiz for a better explanation. https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=40049

HermannTheGerman: Yes, you have it right on Dexit. The MMTer that has written the most on this is Marshall Auerback, but some time ago – some in blogs at places like the old New Deal 2.0 which have become hard to find even using the wayback machine.

For instance: To Save the Euro, Germany Has To Quit the Eurozone

Short-term, one-time adjustments aside, Germany, meaning the people of Germany, isn’t really benefiting from the Euro. They are living quite a bit below their means. What they could do to benefit themselves and the rest of Europe is split the Eurozone and recover the Deutschmark, which would quickly appreciate. They would have to do a lot of fiscal spending to prevent a major recession/depression coming from the export industries. But Germans would have a significantly higher standard of living soon, and there is the example of reunification doing something similar.

This is worrying: https://www.thecanary.co/uk/analysis/2019/01/14/mays-deal-handcuffs-a-future-corbyn-government-deselect-the-labour-mps-planning-to-vote-it-through/

This article states that recent growth in the UK is shown to be more than the rest of the EU but has been due to increasing personal debt which is unsustainable. So isn’t the real conclusion that the Brexit process has had a negligible effect on UK economic growth so far? The Brexit process has resulted in a substantial decline in the value of the pound which although good for most UK businesses does represent a loss in purchasing power for most consumers. The real trade, customs processing and freedom of movement disruptions will occur once Brexit occurs which must harm economic growth at least in the short term post Brexit.

Isn’t the best available policy option for the UK now to adopt the imperfect deal that has just been drafted by Theresa May’s government and the EU apparatchiks given that little time remains, the EU don’t want to make any more concessions and the likelihood that a hard Brexit will be more disruptive in the short term and may not deliver any more in the long term than the current Brexit deal?

I agree Germany, and the rest of Europe, could benefit if Germany left the eurozone but that expansionary fiscal policy is an essential component of such a move. How likely is that? The disruption of manufacturing within Germany would be substantial and Germany would be wise to begin a process of ‘off-shoring’ manufacturing operations to economically weaker European nations many years prior to a eurozone exit.

@robertH

It is my understanding that the UK’s embrace of “free trade” (always a slogan rather than an actual arrangement — all trade is managed trade) suited it as the leading industrial nation at the time and was an expression of the hegemony associated with their mastery of the seas. I believe that this is explained in Ha-Joon Chang’s “Bad Samaritans”

I am prepared to have this thesis falsified and welcome other interpretations with suitable supporting documentation

Yeah I agree with ‘eg’ @14:02. The economic history that I have learned pretty much says England was quite happy to use its colonies as sources of raw materials and not at all willing to allow them to produce and sell manufactured goods that would compete with their own. As the most powerful empire through the 18th and 19th centuries, they were ok with pretending they supported ‘free trade’, but that was mostly because they could prevent most of what they didn’t like when it suited them.

@eg/Jerry Brown

Don’t disagree in essence with either of you, but in detail I do – firstly in emphasis (which is a matter of choice), more importantly in the incorrect (IMO) use of the derogatory phrase “pretending” to support free trade. That’s ahistorical (meaning, viewed through hindsight).

As a matter of historical fact that there was no “pretending” to believe in free trade on the part of people like Cobden and Bright, or their numerous disciples. To them it was a moral imperative.

The fact that it happened to dovetail for a while with Britain’s own interests is an ex post facto construction.

It looks like I wrote too soon regarding the second paragraph in my previous comment and it looks like Theresa May and the EU’s Brexit plan has some nasty aspects. Apparently the so called ‘Backstop’ agreement that would allow Northern Ireland to remain in the EU Customs Union so as to avoid customs formalities for trade between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, includes an agreement that all of the UK would remain in the EU Customs Union as well, to avoid similar ‘mid Irish Sea’ customs formalities between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. This would apply until both the EU and UK agree that it is no longer necessary. The EU Customs Union includes three interrelated areas of EU rules that would place severe restrictions on a future Corbyn Labour government: State Aid, public procurement and nationalization. So presumably one of the first things a Corbyn government would need to do is exit the EU Customs Union which would be politically charged and could take a long time, in which case Corbyn would be wise to attempt to delete this major component of the Brexit deal or reject May’s deal in total and go for hard Brexit.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/05/corbyn-labour-eu-single-market-economic-policy

@ larry:

Not too personal. I trust you more than most random posters on the internet 😉

I’m living in Germany now. In fact, I have a pleasant view of the tower of Mordor, sorry, the EZB building from my flats window.

I’m aware of the need to differentiate between EU vs CU, it was an implicit point of mine (apparently not well made), that the rightist populists in Germany conflate them to either bamboozle their supporters or to avoid talking about the way Germany actually profits from the common currency. Well, as “Some Guy” correctly pointed, it’s not the people but banks and corporations that profit, while the German worker sees his wages stagnate.

@ Some Guy

Thank you very much for the link and your input.

“They would have to do a lot of fiscal spending to prevent a major recession/depression coming from the export industries.”

In my opinion, not many things exceed the German angst of the unemployment & inflation. Maybe their love for 80’s music but not much else. This is rather tragic, because any progressive policy proposal here is shouted down as either a job killer or a threat to cause Weimar-style inflation. Thus, I agree that proper fiscal stimulus should be considered unlikely.

“Germany would be wise to begin a process of ‘off-shoring’ manufacturing operations to economically weaker European nations many years prior to a eurozone exit.”

Which would lead to the dreaded job losses and an even more urgent need for the deficit spending that won’t come to provide for new, more gainful employment opportunities. I confess I have no confidence in any of the currently relevant political players to adress this properly.

@ Hermann

More links:-

google “The Tragedy of the European Union” (George Soros, September 2012)

“Why Only Germany Can Fix the Euro” (Matthias Matthijs and Mark Blyth, Nov 2011)

Tower of Mordor. Wonderful. Love your humor, Hermann.

Hermann, are you familiar with Etienne Mantoux’s The Carthaginian Peace? In it, he argues that the hyperiinflation of the Weimar Republic was engineered in order not to pay the French. While Mantoux is obviously French, Albrecht Ritschl of the LSE agrees with the thesis although he expresses the point somewhat differently, and he is German. I mention this in case someone might think Mantoux was thereby biased. He may have been, but it doesn’t matter. Mantoux’s book was published after the war, altough he wrote it just before. He died in the war.

Ritschl discusses this issue in “The German Transfer Problem, 1920-1933: A Sovereign Debt Perspective”. Another one of his I like is “Deficit Spending in the Nazi Recovery: A Critical Reassessment”. He isn’t an MMTer but I find his perspective and historical comments of interest.

Hermann:- “In my opinion, not many things exceed the German angst of the unemployment & inflation. Maybe their love for 80’s music but not much else”.

Perhaps some might place “Der 90. Geburtstag” oder “Dinner for One” even higher? (being of a yet more venerable vintage).

Whilst Corbyn might be happy with the UK falling out of the EU without a deal so

freeing future governments from some rules it is not a political possibility.

It is not just about all the rest of the parliamentary party that oppose that

but the vast majority of the membership. All those tens of thousands of new members

who joined because of the direction he wishes to lead in. Corbyn has always campaigned

for more membership direction of policy.

It is hard to say why Lexit arguments have had so little traction with labour members.

They are tribal ,passionate, hysterical(I am sure Bill has those emails).

It is simply for them to oppose the bigoted ,far right, nationalist side of Politics.

Robert H, I’ve been called a lot of things but I think this is the first time for ‘ahistorical’. Doesn’t actually seem so bad especially considering that you define it as ‘viewed through hindsight’ :).

Nevertheless, I retract my statement that England ‘pretended’ to support free trade and replace it with England supported a trade policy at that time which they believed to be beneficial to their interests at that time. While this policy shared some similarities with what is called ‘free trade’, those similarities were in fact superficial, and their trade policies for most of the 18th and 19th centuries were more similar to colonial mercantilist policy than ‘free trade’. However, this is in no way meant to question the moral imperatives, or ethical integrity, of the policy makers? Perhaps this would be a less distressing phraseology?

However, this economist seems to have some questions about the moral imperatives involved with British colonial policy. “Britain Robbed India Of $45 Trillion & Thence 1.8 Billion Indians Died From Deprivation” . Just going by the title of the article. Mentions British trade policy from the 17th thru the 20th centuries in a decidedly negative way. Not much ‘free’ about it in her view.

https://countercurrents.org/2018/12/18/britain-robbed-india-of-45-trillion-thence-1-8-billion-indians-died-from-deprivation/

@Jerry Brown

“However, this economist seems to have some questions about the moral imperatives involved with British colonial policy”.

We weren’t debating colonial policy or its moral imperatives (if there were any, which I doubt).

You’re entirely at liberty to be as sceptical as you please of my assertions about the visceral nature of the emotional attachment to free trade displayed throughout much of the C19th by much of the British populace (not just by leading politicians, like Peel and Gladstone) – wrongheaded though it may have been. And by “free trade” they understood – guess what? *tariff* free trade, no more no less. Why impute hidden meanings and sinister motives, on the part of a mass of ordinary people?

Equally I’m at liberty to doubt the sincerity of your so-called retraction in light of the fact that despite it you still seem to me to be importing contemporary political polemics into your reading of history which IMO is A) pointless and B) needlessly distorting of historical truth (or anyway a distraction from a genuine search for it).

Hobsbawm – a lifelong and unregenerate communist hard-liner – seldom or never fell into that trap and in consequence enjoyed an unsurpassed reputation as an historian (amongst appreciative fellow-historians among others).

Yes Robert you are correct to doubt the sincerity of my retraction :). And you are undoubtedly right that it would be wrong to impute sinister motives to a mass of ordinary people who I certainly never met, if only because they lived and died long before I was ever born. And because ordinary people rarely make government policy decisions in any event.

But I don’t really understand your objection to my looking at historical policy and drawing some sorts of conclusions based on reasoned guesses about who benefited and who was in a position most able to affect policy and who didn’t and wasn’t in that position and why. Generally, the motivations for economic gain and political power translate across human history fairly well I would think. Perhaps that method is ‘ahistorical’- but I don’t see why it would be wrong.

@ robertH

Thanks for the links. Fifteen years into my life in Germany and I am still baffled about the whole “Dinner for one” ritual at new years eve. I’ll concede this point to you 🙂

@ larry

I’m not aquainted with Mantoux work, but am intrigued about the proposition. My understanding has always been that the hyperinflation was a result or consecuence of and not a concerted effort against the treaty of Versailles. I understand it as a case of a non-floating currency issuer under a financial constraint because of the repayments (not denominated in the issued currency) it had to make to the victors of the war.

@ Jerry Brown

I think we’ve arrived at a mutually respectful hand-shake, and on this point:-

“But I don’t really understand your objection to my looking at historical policy and drawing some sorts of conclusions based on reasoned guesses about who benefited and who was in a position most able to affect policy and who didn’t and wasn’t in that position and why”

– a polite agreement to differ.

Perhaps we just have unresolved clashing opinions about the “best” approach to history, to try to resolve which would require much more space (and a different forum!).

All the best!

Robert

HermannTheGerman says:

“Fifteen years into my life in Germany and I am still baffled about the whole “Dinner for one” ritual at new years eve. I’ll concede this point to you :)”

Thanks!

You might be even more baffled to learn that the ritual is shared across Scandinavia – and indeed even more widely I understand. As a Brit I look upon it as one of the local natives’ endearing little eccentricities and so join-in indulgently. I find that approach the least stressful and commend it to you too, accordingly.

The EU makes up seven percent of the world, 93 percent of the world is outside of it. We must not neglect wider globalisation of our economy, taking down trade barriers, considering the wider changes happening within the global economy. Building closer trade links with China and America are a must and noting we already export to 160 nations so why the EU being only 27, is a issue. We have received more investment then ever before in our history. Our economy is outpacing the Eurozone and we need to keep on going, household incomes need to rise and we need to get Brexit done before we can make meaningful progress taking any long term approach.