Yesterday (April 24, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest - Consumer…

Monetary policy has failed – we must reprioritise fiscal policy

Remember back in early 2009, when the then head of the European Central Bank Jean-Claude Trichet (boasted that the “euro … is a success … it helps to secure prosperity in participating states”. He was still making these claims in October 2018. At an event in honour of he and former German finance minister Theodor Waigel, organised by the Banque de France, Trichet said that “the euro is a historic success … in terms of credibility, resilience, adaptability, popular support and real growth during its first 20 years is impressive”. He particularly singled out the “delivery of price stability”. Well the latest data confirms beyond doubt that the ECB has failed to deliver on its price stability charter. Further, the descent back into recession in Italy and probably Germany in the December-quarter 2018 tells us that this reliance on monetary policy to stimulate growth while maintaining ridiculous levels of fiscal rectitude has undermined growth and unnecessarily condemned millions to unemployment and rising poverty.

The ECB describe that the objective of its monetary policy is “to maintain price stability”.

They define “price stability” as:

… a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2% … the ECB aims at maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

That would appear to be clear enough and one would certainly allow some latitude around the 2 per cent target in the short run. But that would exclude systematic departures from the target over an extended period.

I will come back to the claim about success in fostering real growth later.

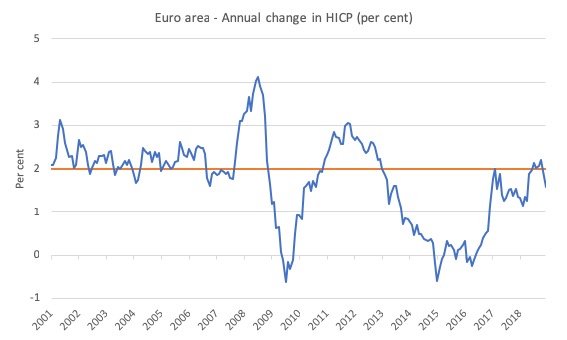

But consider the following graph, which shows the annual inflation rate (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices – HICP) from January 2001 to December 2018 – the span of the euro to date.

The data shows that the inflation rate has been anything but stable under the watch of the ECB.

And, the latest advice from Eurostat is that the annualised inflation rate is likely to drop to 1.4 per cent in January 2019, down from 1.6 per cent in December 2018 (Source):

How does one reasonably interpret this apparent failure?

Given the lack of concerning commentary from the ECB and the sort of boast epitomised by Jean-Claude Trichet’s ‘success’ claims, one interpretation is that the ECB is content with maintaining a deflationary bias in contradistinction to its stated monetary policy objective.

Its behaviour as part of the Troika would support that interpretation.

The other conclusion that could be drawn is that the ECB has just plain failed to fulfill its stated policy mandate.

In other words, the claims that the euro has been a success in terms of maintaining price stability are just nonsensical.

The behaviour of the data is not surprising to an analyst cognisant with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

In the absence of an institutional bias towards inflation (indexation schemes, etc) or a imported raw material (for example, energy) shock, inflation will be low if not negative if aggregate spending growth in the relevant ‘economy’ is weak (in relation to what is required to maintain high pressure and low unemployment).

So the specific lack of correspondence between the actual Euro area inflation rate and the ECB’s price stability target provide us with evidence that the Euro area has been wallowing in a low growth environment, contrary to Jean-Claude Trichet’s other claim in 2018 that the euro has been a “historic success” in terms of promoting strong real growth.

The other interesting conclusion that we can draw in terms of matching the data with the more recent statements from the ECBs President and members of the ECB Board is that monetary policy is largely incapable of generating accelerating inflation.

For example, on July 3, 2014, ECB President Mario Draghi’s – Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A) – announcing the “outcome of today’s meeting of the Governing Council” noted that:

As our measures work their way through to the economy, they will contribute to a return of inflation rates to levels closer to 2% … the key ECB interest rates will remain at present levels for an extended period of time in view of the current outlook for inflation …

… the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to also using unconventional instruments within its mandate, should it become necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation.

So it was clear then that the ECB was pursuing monetary policy – both interest rate setting and the other ‘non-standard’ interventions – with the intent of pushing the inflation rate back to 2 per cent on a stable basis.

It is pretty clear they have not been able to have much influence on the evolution of the Euro area price level.

They certainly haven’t been able to achieve an acceleration in the inflation rate.

This has massive implications for how one assesses the validity of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) viz the dominant mainstream New Keynesian macroeconomics.

The latter has a preference for what they term monetary policy assignment over fiscal policy because they claim that monetary policy is an effective instrument for maintaining full employment and price stability.

The evidence certainly does not support that preference.

It is easy to dismiss this as an issue confined to the Eurozone, given how dysfunctional the architecture of the that monetary system has proven to be.

But the evidence of monetary policy ineffectiveness is also present in Australia (as an example).

Last Wednesday (January , 2019), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) press release – CPI rose 0.5 per cent in the December quarter 2018 – accompanied the latest inflation data for Australia, which showed that the:

CPI rose 1.8 per cent through the year to the December quarter 2018, after increasing 1.9 per cent through the year to the September quarter.

The ABS spokesperson said that:

Over the past four years, annual growth in the CPI has only risen above 2 per cent in two of the past 16 quarters.

The 2 per cent threshold is the lower limit of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s inflation targeting range of 2 to 3 per cent.

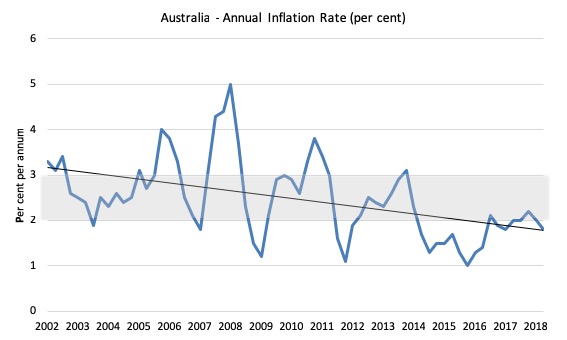

The following graph shows the annual headline inflation rate since the first-quarter 2002. The black line is a simple regression trend line depicting the general tendency. The shaded area is the RBA’s so-called targeting range (but read below for an interpretation).

The trend inflation rate is quite steeply downwards.

The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term. Their so-called ‘forward-looking’ agenda is not clear – what time period etc – so it is difficult to be precise in relating the ABS data to the RBA thinking.

What we do know is that they do not rely on the ‘headline’ inflation rate. Instead, they use two measures of underlying inflation which attempt to net out the most volatile price movements.

For a detailed discussion of these different inflation measures see this blog post – Australian inflation data defies mainstream macro predictions – again (November 1, 2018).

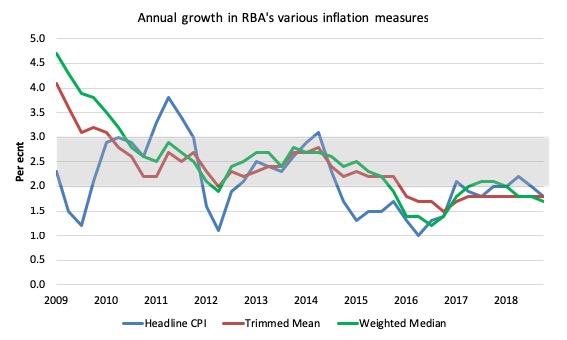

The following graph shows the three main inflation series published by the ABS since the March-quarter 2009 – the annual percentage change in the All items CPI (blue line); the annual changes in the weighted median (green line) and the trimmed mean (red line).

The RBAs inflation targeting band is 2 to 3 per cent (shaded area). The data is seasonally-adjusted.

The three measures are all currently well below the RBA’s targeting range:

1. CPI measure of inflation – 1.8 per cent.

2. The RBAs preferred measures – the Trimmed Mean (1.8 per cent and stable) and the Weighted Median (1.7 per cent and stable).

The evidence is that the RBA has not been very successful at stabilising the inflation rate (any measure) within its target range.

The current divergence away from the lower inflation targeting bound, coupled with a poor national accounts result for the September-quarter 2018 (see blog post – Australian national accounts – economy is slowing and looking shaky (December 5, 2018)), would suggest that the RBA should be cutting rates back down to record low levels.

The commentators are mostly programmed by the New Keynesian macroeconomic bias to call for interest rate cuts when inflation is decelerating.

They have become so dependent on seeing counter-stabilisation (influencing aggregate spending and eocnomic activity) as a responsibility of central banks that they always seek answers in manipulating monetary policy settings.

The problem is that central bank interventions are not very effective nor predictable in terms of counter-stabilisation, as the last decade has certainly taught us.

One commentator who understands this point is Australian Michael Pascoe, who in his recent article (January 31, 2019) – The ‘cut interest rates’ chorus is out of tune with reality.

He wrote that:

The “Reserve Bank must cut interest rates” chorus is growing louder. Too bad it’s barking up the wrong policy tree. Or maybe that should be, singing the wrong tune …

I haven’t met or heard of a single business person in the last couple of years who has said: “You know, I’d like to hire another employee or perhaps invest in a new piece of equipment, but I’m just waiting for the RBA to trim the cash rate another 25 points.”

It is obvious that at present we have:

1. Flat to falling real wages.

2. Sharp declines in housing prices creating a “negative wealth effect” on household consumption.

3. Dramatic slowdown in real GDP growth in the September-quarter 2018.

4. Other indicators such as the “business conditions survey” showing a “sharp downturn”.

5. Weak demand for credit at a time when household debt is at record levels. This is an important part of the story. Mainstream macro holds out that monetary policy can stabilise credit growth. The reality is that credit growth is much more dependent on economic activity and will be weak (strong) no matter what the interest rate is if aggregate spending is weak (strong).

In those circumstances, the RBA can cut interest rates to their heart’s content and there will no stimulatory effect.

Private borrowing will be unresponsive in these conditions.

Michael Pascoe draws the obvious conclusion, which is fully consistent with the basic insights that MMT provides:

Targeted fiscal stimulus could be more effective than rate cuts …

He uses the example of housing policy:

With housing construction slowing, there is an excellent opportunity for governments of all levels to face up to their failure to address social and affordable housing.

A new Productivity Commission report has shown our investment in social and affordable housing has not kept pace with our population.

State governments increasingly outsource government housing to community housing bodies that can’t keep up. Our reliance on individuals to provide rental accommodation also is a factor in our very high household debt levels …

… multiple benefits would flow from governments seriously increasing spending to build more affordable and social housing.

On August 20, 2014, the RBA’s Annual Report for 2013 was considered by the House of Representatives’ Standing Committee on Economics.

The – Hansard – records that the then Governor (Mr Stevens) told the Committee that:

Let me not give gratuitous advice on fiscal policy – and monetary policy is not the answer really for some of the most fundamental things …

He then invited his Deputy (Philip Lowe, now the Governor) to elaborate.

Philip Lowe told the Committee that:

At the end of the day, monetary policy cannot be the engine of growth in the economy. We can help smooth out the fluctuations, but we cannot in the end drive the overall growth in the economy …

I think if we need to invest more and more effectively in education, in human capital accumulation and in infrastructure. Risk taking, education and infrastructure are the things that are going to help us be a high-wage, high-productivity, high value-added economy. The details here are not things that the central bank is expert in, but it seems to me that they are the ingredients to be a successful economy in the next 20 years.

So fiscal policy must be prioritised as MMT economists promote.

The bias towards monetary policy that comes from the dominance of New Keynesian macroeconomics has starved nations of essential spending to maintain high levels of employment and low levels of labour wastage; has led to degraded public infrastructure and education systems; and left a generation of young people with poor prospects (often unemployed for all their youth).

The bias towards fiscal austerity that has accompanied this bias towards monetary policy is undermining the prosperity of the next generations.

And now we go to Italy …

And we don’t have to look very hard to see how that austerity bias is playing out in the Eurozone.

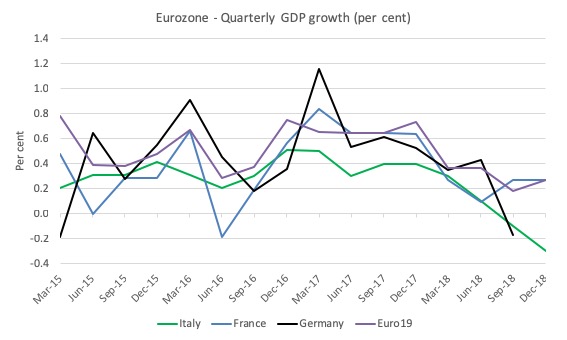

Eurostat latest national accounts data released last week (January 31, 2019) – GDP up by 0.2% in the euro area and by 0.3% the EU28 – shows the Euro area growth rate was 0.2 per cent in the December-quarter 2018.

It was 0.2 per cent in the third-quarter and half the growth rate in the first two quarters of 2018.

The annual growth rate has fallen from 2.4 per cent (March-quarter 2018) to 1.2 per cent (December-quarter) and will fall further in the March-quarter 2019, when the data is available.

Close to stagnation.

The data for the individual Member States shows that:

1. Italy contracted by 0.3 per cent in the December-quarter and is now back in official (technical) recession. The third recession in a decade – a disastrous outcome and unambiguous testament of the way the common currency has failed that nation.

2. It is likely that Germany will also record a second consecutive quarter of negative growth

The German statistical agency – Destatis – informs us that (Source):

General government achieved a record surplus of 59.2 billion euros in 2018 (2017: 34.0 billion euros). At the end of the year, central, state and local government and social security funds recorded a surplus for the fifth time in a row, according to provisional calculations. Measured as a percentage of the gross domestic product at current prices, this was a 1.7% surplus ratio of general government for 2018.

This is a huge drag on the economy and it is no wonder it is heading back into recession.

The following graph shows the quarterly real GDP growth in the three large Eurozone economies over the last three years. It has been all downhill for the last two years.

When the new Italian government outlined plans to expand the fiscal deficit (for one year only, ffs) the technocrats in Brussels moved in quickly to choke any hope of expansion off.

The ECB allowed that bullying to be realised by letting the spreads on Italian government bonds against the bund to rise quickly, creating a sense of impending financial crisis.

On January 14, 2019, the Banca d’Italia released its latest results for its – Survey on Inflation and Growth Expectations – 2018 Q4.

This is a survey of “industrial and service firms” which examines “the firms’ expectations for consumer price inflation, developments in their own selling prices, and their views on the macroeconomic outlook.”

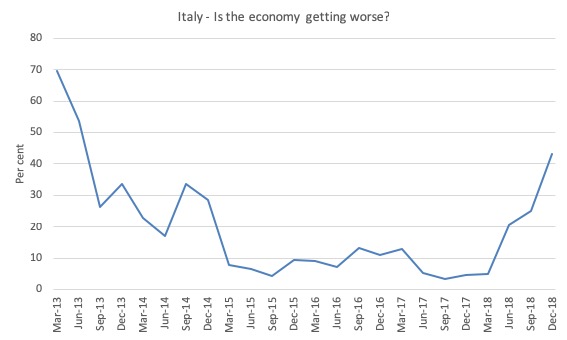

The following graph shows the proportion of worse responses to the question “Assessment of the general state of the economy with respect to previous quarter”.

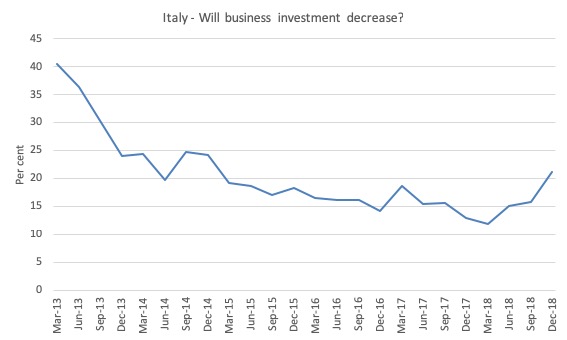

That pessimism then drives business firms in Italy to reduce their planned investment as the following graph shows.

So the proportion of business firms in Italy that expect to decrease investment has risen sharply in the last 6 months.

This will not only affect economic growth over the next few quarters (via the direct expenditure effect) but also reduce potential growth (via the supply-side effect).

Three recessions in a decade is a sign of major policy failure.

It is hard to see it in any other terms given that appropriate use of fiscal policy can always prevent a recession from occurring.

Conclusion

So two things arise.

First, central banks around the world have been using ‘loose’ monetary policy as a tool for accelerating inflation and have failed.

They believed in the New Keynesian (mainstream macro) model and it has shown itself to be a failure.

Second, this bias towards monetary policy overlaid with the rampant neoliberalism of the European Union’s pet baby, the common currency, has derailed reasonable fiscal policy interventions and its largest economies are heading ‘south’ again.

And then they wonder why people want to leave the EU, or march in the streets in yellow vests, or elect far right politicians who give voice in the absence of any effective Left engagement to the peoples’ angst.

Call for financial assistance to make the MMT University project a reality

I am in the process of setting up a 501(c)(3) organisation under US law, which will serve as a funding vehicle for the MMT Education project – MMT University – that I hope to launch early-to-mid 2019.

For equity reasons, I plan to offer all the tuition and material (bar the texts) for free to ensure everyone can participate irrespective of personal financial circumstance.

Even if I was to charge some fees the project would need additional financial support to ensure it will be sustainable.

So to make it work I am currently seeking sponsors for this venture.

The 501(c)(3) funding structure means you can contribute to the not-for-profit organisation (which will be at arm’s length to the not-for-profit educational venture) in the knowledge that your support will not be publicly known.

Alternatively, if you wish to have your support for the venture publicly acknowledged there will information presented on the Home Page of the MMT University to acknowledge that funding.

To ensure the project has longevity I am hoping to obtain some long-term support proposals.

At present, I estimate I will need about AUD 150k per year.

Note that most of these funds will support an administrative support staff (1 person fractional), data charges, and video editing and design staff (as needed).

I will personally take no payment for the work I am putting into the project nor will other core Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) academics, who have agreed to help in the educational program.

So I cannot do this without sufficient support. My research group does not have the financial capacity to support this venture.

I also do not wish to place advertisements on my blog posts.

You will be contributing to a progressive venture.

Please E-mail me if you can help.

I have some funding pledges already but I am not near the target yet.

It will not happen if I cannot get the support.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

So neoliberal austerity policies really do work? Will the slide into authoritarianism be repaired by exiting the euro?

https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/02/01/trumps-brilliant-strategy-to-dismember-u-s-dollar-hegemony/

This article, if it survives the spam action, illustrates Michael Hudson’s remark that the PTB deliberately targetted the Left to get their neo liberal Austerity agenda across. They took the right for granted so now we see what Michael describes here

Heim, I’m afriad I don’t understand the basis of your questions. Neoliberal austerity policies never work. And exiting the Euro may or may not stop any slide into autoritarianism, depending on what else is going on.

The Euro, as an actual currency, is a success for rich capitalists. It has achieved exactly what they wanted: relative price stability for their preferred consumption items and asset valuation rises for their asset portfolios. The damage done to the lives of poor people, the precariat and base wage workers, is of no consequence to the rich capitalists, their functionaries and political enablers. These classes care nothing for ordinary people.

I have long been of the opinion that neoliberals know exactly what they are doing and practice economics entirely in bad faith. It was always their intention to drive wages down to a bare minimum, to keep a reserve army of unemployed and to concentrate almost all wealth in the hands of a very small number of billionaires and multinational corporations. This was the plan all along no matter what their protestations about caring for all of the economy or all of the people.

They (neoliberals) have managed expectations marvelously. People now expect unemployment to be 5% and underemployment 15% (if they even know what underemployment is). People now expect politicians to lie all the time, government to be ineffective and rich people and corporations to simply do whatever they like.

People now expect and conceive of all neoliberal developments as being inevitable and irreversible. The supposed “inevitable and irreversible” nature of neoliberal economics has been deeply ingrained into people’s thinking by the propaganda of the entire neoliberal system and its instrumental effectiveness in getting its own way. In addition, many steps have been taken to radically change the institutional nature of society as a whole in order to embed, so far as possible, the irreversibility of neoliberal change as a structural feature. Institutions which could have provided avenues for reversing changes were systematically dismantled.

Governments are deliberately starved of funds. Tax cuts for the rich are preferred, not only for their direct effect of enabling the rich to get richer, but for their indirect effect of starving the government of funds. Then governments are more or less barred from running deficits. Combine these factors and you get a government seriously starved of funds. Artificially create security, terror and war “threats” to ensure what spare money the government has is shoveled straight back to the military-industrial-financial complex. A government starved of funds is weaker, less effective, less able to regulate and control big business. At the same time big corporate business is rolling in funds, paying almost no taxes, hiding funds in tax havens and getting massive extra kick-backs from the frauds of Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) and international “free trade” agreements which favour corporations over consumers and governments.

This was all intended from the first. The way was paved by thinkers like Hayek, Mises, Friedman and the Chicago School. It was laid out in broad programmatic form in the “Omega Project” developed by The Adam Smith Institute under the leadership of and implemented, in its first stages, by Margaret Thatcher. The first (I think) Omega Project plan dealt with “Local Government, Planning and Housing” in 1983. Read that plan and you can see the nascent recommendations for privatizing government services. (Go to page 60 of the document and peruse the “The Main Proposals”.)

There are a host of other Omega reports from that era. They lay out almost the entire neoliberal manifesto and strategic plan for radically re-shaping our economy as neoliberal, that is to say as market fundamentalist with a large bias to oligopoly and corporatism. This project is a matter of public record. You can find it on the Omega Project page of the Adam Smith Institute. So, it’s not conspiracy theory, it’s conspiracy fact. Whilst not legally a conspiracy it is morally and ideologically a conspiracy.

The neoliberals (forget when they actually took or were given that precise name) had a plan; an extensive strategic plan. This is as opposed to the left in the West who were plan-less and clueless and still remain so. The collapse of Communism and Marxism left the left without an intellectual foundation. (There’s a broad discussion around this point which would make this post too long.) Keynesian economics and welfarism still essentially belonged to the paradigm of capitalism and “fought” or advocated from a still capitalist (albeit mixed economy) position. When you fight in the paradigm of the enemy’s system on the enemy’s chosen intellectual ground with the enemy’s chosen mobilization methods and the enemy has far more resources than you then you will lose. This is the lesson history has taught us since 1973.

Of course, this post would get too long if I continued here with this analysis. Suffice it to say that some Marxians (two notables working independently, so far as I know, are John Bellamy Foster and Richard D. Wolff) are laboring on producing the analysis and the blueprints for practical actions to overcome the intractable impasse into which late stage capitalism has led us and which will remain intractable (and indeed biospehere destroying) unless make a complete and radical change to a new system.

Worth reading is “Capitalism Has Failed-What Next?” by John Bellamy Foster.

Worth watching is “Democracy in the Workplace” by Richard D. Wolff.

Bill, why spend so much time explaining why monetarism doesn’t work; we all know it doesn’t work. Warren Mosler’s description of the Fed being like a person trying to steer a car down a curvy road by sitting in the back seat and leaning side to side is an apt description. Yet the Fed does serve that one important purpose: a safety net under the economy that exists only because of a fiat currency. This function saved us in October of 1987, the Long Term Capital Management failure in 1998 and the Mortgage Crisis of 2008 and 2009. In essence the one critical MMT characteristic was reflected in the Fed “writing the check.”

@Ikonoclast says:

15:24

Absolutely agree on that conclusion, neo-liberalism hasn’t failed, a tremendous success. If one measure if it has achieved its primary goal.

Only a child could believe that a minority of the ruling establishment that owns the economic resources have identical interests in national economy with the many and not least the precariat.

So, it had to be sold with pipe dreams of “potential” side effects.

Social democracy and a lost clueless left, infiltrated with economists educated in neoliberalism, swallowed it willingly. Easier to go with the common narrative than to take the fight, and definitely more profitable for their elite.

”

And the clueless left bought it, that it was a real crisis of capitalism, they could just bench on the spectator bleachers and see capitalism self-destruct as Marx or whoever it was had predicted.

Now when the economic part are fulfilled they start to hack in on democracy, with right wing nationalists as a excuse.

Their grip on economic power and not least media and its “reality” description are probably on another magnitude today than it was 100 years ago. They will do what ever it takes to protect their gains. Not even the crash of 1929 and great depression rocked the boat that much, it did take a world war to do that.