It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

German growth strategy falters – exposes deep flaws in the EU architecture

Last week (February 14, 2019), Eurostat released its latest national accounts estimates – GDP up by 0.2% and employment up by 0.3% in the euro area – which confirmed that EU growth rates have declined significantly over the course of 2018. Moreover, the December-quarter data confirmed Italy is in official recession and Germany recorded zero growth (thereby avoiding the ‘technical recession’ category after contracting by 0.2 per cent in the September-quarter). Export expenditure accounts for nearly 50 per cent of Germany’s GDP – a massive proportion. It has adopted a growth strategy based on impoverishing its own residents through flat wages growth and a sustained proportion of low-paid, precarious jobs and setting its sail on sucking out expenditure from other nations (in the form of their imports). This has been particularly damaging to the Eurozone partners but also exposes Germany to the fluctuations in world export markets. Those markets are softening for various reasons (economic and political) and, as a result, German growth has hit the wall. The solution is simple – stimulate domestic demand, push for higher wages for workers, outlaw Minijobs, and start fixing the massively degraded public infrastructure that the austerity bent has starved. Likelihood of the German government adopting that sort of responsible policy. Zero to very low. There is the problem of the Eurozone from another angle. The main economy cannot play the game properly.

I considered the first release of the European national accounts data (from December) in this blog post – Nations heading south as austerity continues (February 6, 2019).

I also considered aspects of Germany policy strategies in this blog post – Germany – a most dangerous and ridiculous nation (December 27, 2017) – which also provides several links to related analysis that I have presented over the years.

A study of the German National Accounts provides for an interesting story. The following sequence of graphs provides the imagery. They are indexes (March-quarter 2000=100), except for the last two graphs (which are expressed as proportions of GDP).

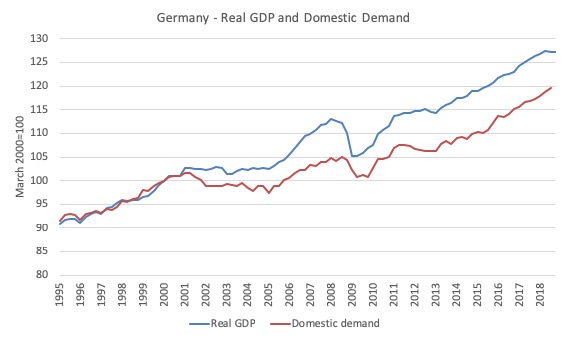

The first graph shows the evolution of Real GDP and domestic demand (consumption and investment) from the March-quarter 1995 to the December-quarter 2018 for GDP and September-quarter 2018 for Domestic demand (latest available data).

They are indexed to 100 at the March-quarter 2000.

Since that time, GDP in Germany has grown by 27.2 per cent, whereas domestic demand has grown by just 20.9 per cent (in real terms).

There are two very interesting things about the graph apart from the divergence between total spending (GDP) and domestic-based spending (domestic demand).

First, you can see the suppression of domestic demand began soon after the inception of the euro – the Hartz devastation (see below).

Second, look what happened after 2011, as the fiscal austerity moved into top gear. While real GDP grew on the back of the growing exports, domestic demand fell between June 2011 and June 2013, further exacerbating the Eurozone crisis.

That evolution was the result of deliberate policy positions taken by the German government.

By deliberately constraining the standard of living of its citizens and undermining its own public and private infrastructure, the German government also damaged its EMU partners.

Remember that an export-based growth strategy requires a nation to feed of the spending of other nations and pushes those nations into external deficits, which require, among other things, fiscal deficits to support growth and domestic savings desires.

Imposing fiscal austerity in that context on the importing nations only exacerbates an already imbalanced situation, which Germany’s single-minded policy strategy created.

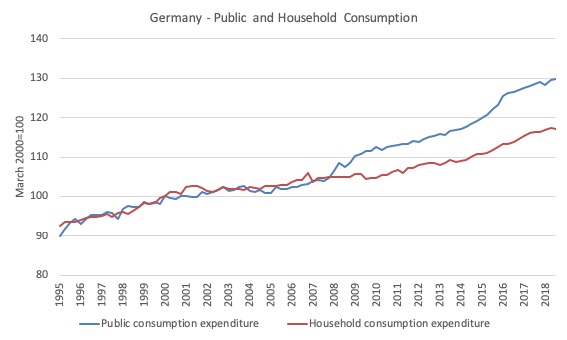

The next graph shows the evolution of consumption expenditure (public and household) over the same period.

Two things stand out:

1. The suppression of consumption expenditure both public and private in the first seven years after adopting the euro. This was tied in to the growing imbalance in the mix of expenditure driving growth in Germany (see below).

2. The on-going suppression of household consumption growth. While real GDP has grown by 27 per cent since the March-quarter 1995, household consumption expenditure has grown by just 17 per cent (very poor).

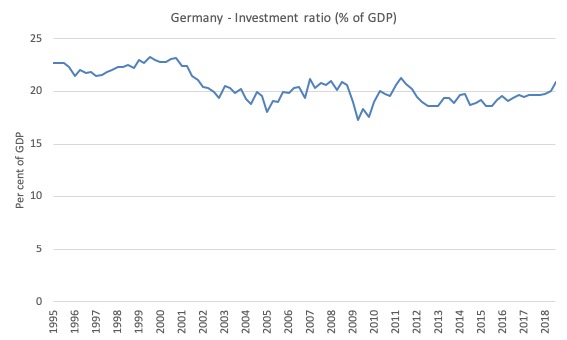

The next graph shows the German investment ratio (as a percent of GDP) over the same period.

It has declined from 23.3 per cent in the September-quarter 1999 (just before the euro adoption) to its current level of 20.9 per cent.

This decline has two implications:

1. Less expenditure is coming from capital formation, which affects the current growth rate.

2. The declining investment ratio impacts negatively on potential GDP, which means the productive capacity of the German economy is being undermined.

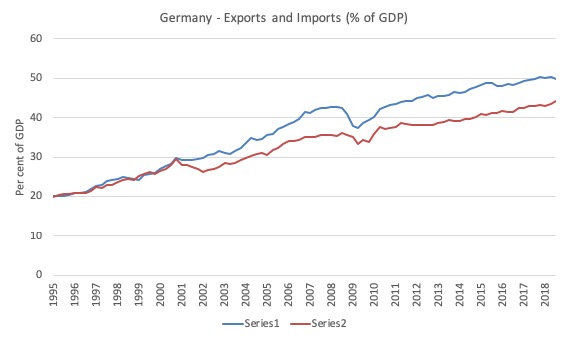

The next graph ties this altogether and shows the trade components of the Current Account balance as a share of GDP.

This is a very dramatic history.

Prior to the adoption of the euro, Germany was increasing its openness to world trade but more or less in proportion – exports and imports were rising as a share of total GDP.

But from the point Germany adopted the euro, it changed strategy entirely and began its export mania while suppressing import expenditure via suppression of domestic income growth. I will discuss the evolution of minijobs below.

German exports of goods and services has moved from being around 20 per cent of GDP in 1995 to 49.8 per cent of GDP in the third-quarter 2018.

That is a massive structural shift and comes at the expense of the material well-being of the German people who have endured an increase in precarious employment, flat wages growth, and largely flat consumption spending.

Throughout 2018, the export ‘miracle’ has faltered and that helps to explain the dramatic GDP slowdown. Clearly German exports are being negatively impacted by the US trade shenanigans and the slowdown of the Chinese and British economies.

Clearly, it looked beyond Europe for export growth, knowing that its enforcement of austerity within Europe, has seriously impaired its capacity to grow via intra-European exports.

All these trends can be tied together easily and related to the on-going malaise in Europe.

Germany’s ongoing violation of the EUs Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure – as a result of it consistently exceeding the external deficit threshold of 6 per cent of GDP, has had ramifications through the Eurozone.

By dramatically reorienting its economic growth strategy away from a balance between domestic and external expenditure, through a combination of wages growth suppression, fiscal surpluses etc, Germany has been accumulating financial claims against the rest of the world.

How might this imbalance be resolved? There are a number of ways possible.

A most obvious solution would be for foreigners to borrow funds from the domestic residents. This would lead to a net accumulation of foreign claims (assets) held by residents in the surplus nation.

Another solution would be for non-residents to draw down local bank balances, which means that net liabilities to non-residents would decline.

Thus a nation running a current account surplus will be recording net private capital outflows and/or the central bank will be accumulating international reserves (foreign currency holdings) if it has been selling the nation’s currency to stabilise its exchange rate in the face of the surplus.

Current account deficit nations will record foreign capital inflows (for example, loans from surplus nations) and/or their central banks will be losing foreign reserves.

Large current account disparities emerged between nations in the 1980s as capital flows were deregulated and many currencies floated after the Bretton Woods system collapsed.

European nations such as Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland were typically recording large and persistent current account surpluses and with a significant proportion of their trade being with other European nations, the imbalances grew within Europe as well as between Europe and elsewhere.

Think about the sectoral balances arithmetic. If a Member State achieve a balanced fiscal outcome and is sitting on the current account surplus threshold (6 per cent), then its private domestic sector will be saving overall 6 per cent of GDP.

Where will those savings go?

I have discussed how Germany maintained its external competitiveness once it could no longer manipulate the exchange rate in previous blogs.

Please read my blog posts:

1. Germany is not a model for Europe (March 2, 2015).

2. Germany should look at itself in the mirror (June 17, 2015).

The savings may go into the domestic economy if there are profitable opportunities to invest. But in Germany’s case, its whole strategy was based on suppressing domestic demand (Hartz reforms, wage suppression, mini-jobs etc), and so profitable investment opportunities were limited in the German economy.

As a result, German capital sought profits elsewhere.

The persistently large external surpluses which began long before the crisis (and 6 per cent is large) were the reason that so much debt was incurred in Spain and elsewhere. German investors pushed capital externally.

The combination of domestic demand suppression and huge external surpluses means that Germany’s outflow of capital is ridiculous.

The imblance in Germany then becomes an imbalance elsewhere and given the dominance of intra-European trade, those resulting imbalances make life precarious for the weaker European nations.

To resolve this problem (which is a massive imbalance between domestic saving and investment), Germany requires higher domestic demand and faster wages growth, both to boost the very modest consumption performance and to attract investment into the domestic market.

It also could stimulate public spending – say, to start the long process of restoring quality to its public infrastructure which has been seriously degraded by the austerity mentality of successive German governments.

But such a change would be at odds with the mercantile mindset that dominates the nation because it would reduce the competitive advantage that Germany enjoys over other nations that have treated their workers more equitably.

The Minijobs are now a permament feature of Germany

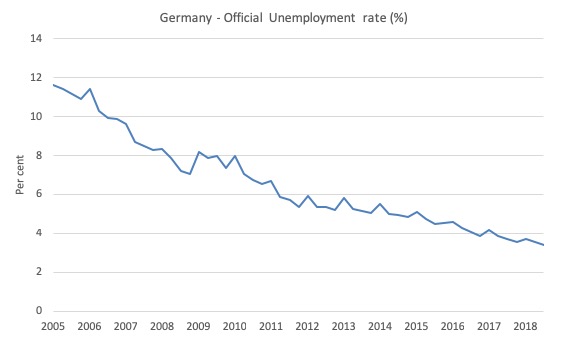

The official unemployment rate in Germany is low by any standards (other than full employment). In the September-quarter 2018, it was recorded at 3.8 per cent.

The following graph shows the evolution since the March-quarter 2005.

However, the reduction in official unemployment has really only been achieved by shifting the weak demand into precarious, low-paid positions.

Once the common currency emerged and Germany lost the ability to manipulate its exchange rate to its advantage (forget the rest), the next strategy it employed was to attack its own workers.

A reasonable argument can be made that Gerhard Schröder helped cause the Eurozone crisis. His government’s response to the restrictions that Germany encountered on entering the EMU are certainly part of the story and one of the least focused upon aspects.

Upon entering the EMU, Schröder was under immense political pressure to do something about the high unemployment in the East after reunification.

Without the capacity to manipulate the exchange rate, the Germans understood that they had to reduce domestic production costs and inflation rates relative to other nations, in order to retain competitiveness.

The Germans thus took the so-called ‘internal devaluation’ route well before the crisis; a move, which ultimately made the crisis worse for other Eurozone nations.

When Schröder unveiled his Government’s ‘Agenda 2010’ in 2003, it was clear that they were going to hack into income support systems and ensure that Germany’s export competitiveness endured despite abandoning its exchange rate flexibility.

It was dressed up in the language of flexibility and incentive, but was based on the mainstream view that mass unemployment was the result of a workforce rendered lazy by the welfare system, rather than the more obvious alternative, that it arose due to a shortage of jobs.

The so-called ‘Hartz reforms’ were a major plank of the strategy and resulted from a 2002 commission of enquiry, presided over by and named after Peter Hartz, a key Volkswagen executive.

The aim was clear, unemployment benefits had to be cut and job protections had to go. The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schröder government and introduced in four tranches: Hartz I to IV, starting in January 2003.

The changes associated with Hartz I to Hartz III, took place over 2003 and 2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005.

The changes were far reaching in terms of the existing labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The so-called supply-side focus saw unemployment as an individual problem and advocated that continued income support should be conditional on a raft of increasingly onerous activity tests and training schemes.

Further, governments abandoned their responsibility to reduce unemployment with properly targeted job creation schemes.

Public employment agencies were privatised spawning a new private sector ‘industry’ – the management of the unemployed!

The Hartz reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market and the precariousness of work increased. Hartz II introduced new types of employment, the ‘mini-job’ and the ‘midi-job’ and there was a sharp fall in regular employment as a consequence.

Mini-jobs provide marginal employment with no security or entitlements and allow workers to earn up to 450 euros per month without paying taxes, while the on-costs for employers are significantly lower. The no tax obligations also mean that the worker receives no social security protection or pension entitlements.

The neo-liberal interpretation of these changes is that Germany underwent a ‘jobwunder’, or jobs miracle.

However the speedy increase in employment that followed (and the decline in official unemployment) can also be viewed less optimistically.

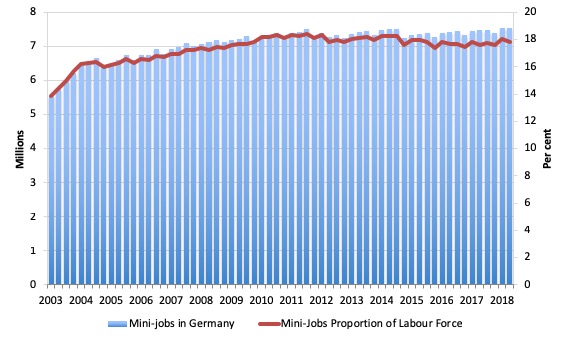

The following graph charts the history of the mini-jobs since 2003.

In September 2018, there were 7.56 million ‘mini-jobs’, which represented 17.9 per cent of the labour force between 15 and 64 years of age.

The proportion has been fairly steady since late 2007 after a rapid increase in the earlier years of the scheme. However, it is starting to rise again, albeit slowly.

The rapid increase in mini-jobs meant an increasing (and sizeable) proportion of the German workforce were forced to work in precarious jobs with extremely low pay and were excluded from enjoying the benefits of national income growth and the chance to accumulate pension entitlements.

Profits win out over wages

The Government in cahoots with industry also engineered a massive redistribution of national income to profits and away from wages.

In general, German real wages (the purchasing power equivalent of the wages received by workers each week) failed to keep pace with growth in productivity (how much workers were producing each hour) and as a result there was a massive redistribution of national income to profits.

The following graph shows the – AMECO – (Annual Macroeconomic) database measure of Real Unit Labour Costs, provided by the European Commission.

RULC are the ratio of real wages to labour productivity and if they are falling it means that productivity growth is rising faster than real wages and redistributing national income towards profits.

So the RULC measure is equivalent to the share of wages in national income. If it falls, workers have a lower share in real GDP.

After Germany adopted the euro, there has been a 3.53 per cent swing to the profit share at the expense of workers.

The rise in the shares during the crisis signifies the fact that national GDP (output) was falling while total wages were not falling as fast or were relatively constant. As a consequence the ratio of the two rose.

Why does this matter? Until the early 2000s, real wages and labour productivity had typically moved together in Germany as they did in most advanced nations.

If real wages and labour productivity grow proportionately over time, the share of total national income that workers (wage earners) receive remains constant.

However, once the neo-liberal attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified in the 1980s in many nations and, later in Germany, a gap between the growth in real wages and productivity growth opened and widened.

This led to a major shift in national income shares away from workers towards profits.

The capitalist dilemma was that real wages typically had to grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold. If workers were producing more per hour over time, they had to be paid more per hour in real terms to ensure their purchasing power growth was sufficient to consume the extra production being pushed out into the markets.

How does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in the real wage, especially as governments were trying to reduce their deficits and thus their contribution to total spending in their economies? How does the economy recycle the rising profit share to overcome the declining capacity of workers to consume?

The neo-liberals found a new way to solve the dilemma. The ‘solution’ was so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever-increasing debt onto households and firms in many nations.

The credit expansion sustained the workers’ purchasing power, but also delivered an interest bonus to capital, while real wages growth continued to be suppressed.

Households in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed too good to be true and it was.

Germany adopted a particular version of this ‘solution’.

The funds to underwrite this credit explosion came from the increased profits that arose from the redistributed national income.

For some nations, such as Germany, the large export surpluses also provided the funds to loan out to other nations.

Germany didn’t experience the same credit explosion as other nations. The suppression of real wages growth in Germany and the growth in the (very) low-wage ‘mini-jobs’ meant that Germany severely stifled domestic spending.

Schröder’s austerity policies forced harsh domestic restraint onto German workers, which meant that Germany could only grow through widening external surpluses.

So the external strategy, which has caused irreparable harm to its Eurozone partners, has also impoverished its own population. The German approach, which is echoed in the basic design of the common currency and the fiscal and monetary rules that reinforce it, could never be a viable model for prosperity throughout Europe.

Conclusion

And now with the world export demand declining for various reasons, the vastly unbalanced German economy is faltering.

Germany has adopted the strategy that it can permanently game its Eurozone partners through its mercantilist approach.

The massive external trade surpluses, which then manifest as capital exports to its Eurozone partners, not only generate low returns for the investors but further complicate the debt dynamics within the union.

The German population do not win, nor do Germany’s partners.

And when the world export demand softens, the whole show becomes shaky again.

Another demonstration of the unviable nature of the common currency.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A timely and masterful exposé.

It begs the question:- is Germany’s “beggar-my-neighbour” (aka mercantilist) policy consciously and deliberately malign in intent? Some have suggested the answer is “yes”.

For my own part, I strongly doubt that. It seems to me more like a classic demonstration of the law of unintended consequences in full-blown operation. Misguided? Definitely – crassly so. Malign? No (where’s the evidence?). I don’t detect any implication in Bill’s studiously factual account that Germany’s elite has been pursuing any deeply-sinister plan aimed at European – if not world – domination.

For that (the latter) you need to look across to the other side of the Atlantic.

Dear RobertH (at 2019/02/19 at 6:20 pm)

Evidence? The Hartz Changes – deliberate strategy to suppress the ability of German workers to be able spend.

That is the start of it.

Why? To ensure that Germany could maintain competitiveness in the Eurozone and knowing that the other lower productivity nations would have to cut wages severely to stay competitive.

And on it went.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

With the greatest respect (and I mean that sincerely) I think that here you are departing from a strictly factual narrative and introducing polemics. (Nothing wrong with polemics BTW – so long as they’re acknowledged as such).

I guess it depends on the meaning given – in this context – to the word “malign”. As we all know it can have various meanings (a “malign” or “malignant” cancer for one) but i think they all share a common characteristic – namely that at least when carried out by a sentient being the intent is evil (to do harm to another) and that that is its deliberate purpose. That was what I asked for evidence of, and I’d be very surprised if you seriously intended to ascribe so great a degree of conscious malevolence to Germany’s policy-makers (even Schroeder, for whom I personally have no time at all). That’s certainly not how I read your account.

Best regards

Robert

“Germany – a most dangerous and ridiculous nation”

Seldom have I read a sentence as poignantly true, funny and sad.

Is it a sign of madness that I find myself understanding those bunker survivalists in the US a bit better everyday and that I begin to trust their instinct more than our “very serious” European leaders?

On a different topic, someone needs to adress Krugman’s OP in the NYT ASAP:

“Now, I am not a fan of MMT, which is basically Abba Lerner’s “functional finance,” which while clever missed some possibly important things. I explained all of that in a previous post. But the truth is that none of this matters much for the issue at hand. Even if you’re a committed Lernerite, even if you think that debt never matters, the sheer scale of what progressives would like to accomplish means that there will have to be tax hikes to pay for most of it”

Even for a laymen like myself, this level of reductionism and the non-sequitur that follows is way over the top: Firstly, MMT =! functional finance or it would be called just that, functional finance. Secondly, how does it follow that tax hikes are inevitable if debt doesn’t matter?

Maybe Krugman intends to say that the debt shouldn’t be the issue right now and if tax are what is (politically) needed to pass the necessary infrastructure and public spending bills, then so be it. I could live with that. But then:

“But if the economy can’t expand as much as a multiplier says it “should” after an unfunded introduction of Medicare for All, what would happen? Inflation. Big time. Either that or the Fed would have to raise interest rates by a lot, crowding out a lot of private investment.”

Inflation and “crowding out”. That from the guy that professes to live fighting “zombie-ideas”. He does argue using Okun’s Law, but he estimates the employment %-delta per GDP %-delta at about half the value Bill gave in his post on Okun’s Law dated Jan 22, 2013 (and Bill presents his data whereas PK simply says he “ran regressions”).

“[…] the issue right now and if tax HIKES are what is (politically) needed […]”

Never type when excessively angry…

@robertH and @bill

Robert, Bill,

you engage in a new itereation of the discussion we’ve been having for the last couple of days: bad intent or incompetence/short sightedness.

I tend to agree with robertH when I think of a Merkel/Schäuble- or even Schröder-like politician who is not so versed in economics but either a technocrat who’ll listen to his/her “smart men” or an ideologue who’ll listen to those “smart men” who provide economic cover for his agenda. Some would say Schröder is in a category for himself: an unrepentently selfish, unabashedly corrupt but charismatic cynic. I would agree with them.

After the discussions we’ve had here I think that you are both right. Most politicians act out of ignorance of the concesecuences of their decisions, while most of those “smart men” know exactly what their policy proposals mean and will deliver. Problem is, the legislative stage ends co-opted by corporate interests anyway. So, does it even matter?

However, not one of those politicians is dumb nor blind so they are all condemnable for refusing to see the suffering and acknowledging it as the result of the policies they either championed or at least supported.

I’ll let the historians sort out whether the death of Europe was a murder or manslaughter.

HermannTheGerman:- “I’ll let the historians sort out whether the death of Europe was a murder or manslaughter”.

Le mot juste!

Hermann, “I find myself understanding those bunker survivalists in the US a bit better everyday”. Oh, dear. Should I worry about your sanity? 🙂

Your point about Krugman is well taken. He really doesn’t know what he is talking about half the time. And I do mean half the time. The other half, while sensible, isn’t very deep. His idea of being wonkish, as he puts it, is to add a graph with no axis labels. I’m not making this up. In the instance you brought up, he is out of his depth and, hence, uttering bullshit. You seem to me to know more about this than Krugman does, even though he is at Columbia and previously at Princeton. Such individual social status doesn’t always mean what it appears to mean, but that is another long, and different, story.

By the way, he supported HRC in her presidential bid. His politics is like his economics, not entirely sound. Another aside, he apparently, according to his own account, teaches undergraduates the IS/LM curve because it serves as a good introduction. Hicks repudiated this distortion of Keynes at the end of his life. Go figure.

I’ve just recommended this blog as a comment on https://www.ft.com/content/018c4ce6-2ef8-11e9-8744-e7016697f225 ;o)

@larry:

“Oh, dear. Should I worry about your sanity? :-)”

I know I do. With my girlfriend that would be three of us 🙂

“You seem to me to know more about this than Krugman does, […]”

Flattered as I am, this is of course not the case. I think that when you’re at the highest echelions of economics as PK is, academia and politics get so entangled with eachother, that you must make concessions in order to stay relevant. Or even sane. As you say, quite often he seems to let his politics influence his economics a bit much. I suspect his personal affiliations and immediate environment play a role in it, too. Not everyone is akin to “rock the boat” and risk social ostracization. I guess he’d at least lose his column at the NYT if he rocked it a bit too hard. I, on the other hand, always bring a good bottle of wine with me to parties, so aside from the ocassional frown and the “not that guy again” snide remark, I expect to keep being invited and thus have fairly little to lose 🙂

Full disclosure: the PK column was for a long time my go to source for insight on economics so I like to think of it as a sort of a first step towards leaving the mainstream. For example, you can look up how he, too, denounced the Germans as “dangerous and ridiculous” and called their behavior towards Greece “sadomonetarist”. At a time when the German consensus was that the Greeks had “lived beyond their means” it was a welcome take on the issue for me.

Cheers!

A lot of jobs in Germany are now dependent, not only on exports, which is true everywhere, but on an export surplus. If the export surplus is brought down to zero, there will be massive unemployment and spare capacity in industry. Stimulation of domestic demand and reduction of foreign demand through rapid wage increases will mean that there will be a massive shift in demand from industry to services.

Suppose that 60% of the cars produced in Germany are exported. A reversal of mercantilism could mean that half of those exports will disappear. German car buyers will not be able to make up for this decrease, and the result will be that the auto industry in Germany will shrink significantly, unless Germany can curb auto imports. That’s one problem with mercantilism. It can only be reversed by causing severe dislocations.

I can’t help thinking that Bill has an anti-German animus. Otherwise he would point out once in a while that Dutch economic policy is the same as the German one, and it was initiated earlier. The polder model of Wim Kok’s cabinets (1994 – 2002) was the equivalent of Schröder’s Agenda 2010. It is sad that both Wim Kok and Gerhard Schröder are social-democrats. It is therefore fitting that the Dutch Labor party collapsed and that the German SPD is in free fall in opinion polls.

Be that as it may, the average Dutch current account surplus of the last 10 years has been higher than the German one. The Dutch are even bigger mercantilists than the Germans. Full disclosure: all my known ancestors are Dutch. The biggest mercantilists of them all may well be the Swiss. Norway is a special case because of its massive oil exports.

Regards. James

@ James Schipper

I concur. However, it’s the size of the German economy and their bigger influence in European institutions that make them the most visible target. The dutch let the Germans play the bad cop role but neglect to play the part of the good cop.

A relative of mine has been living in the Netherlands for half a decade now and confirms your sentiment on an intrapersonal level. She describes them as “still a nation of pirates”, “swamp germans” or “cutthroats with a smile” 🙂

After visiting me in Germany, however, she found herself missing the part with the smile.

Bill,

Any thoughts on when those on mini jobs etc are due to retire without any pension funds?

Will they solely rely on state aid or expected to keep working and the economic effects?

Regards

One way that historians will know that those responsible were guilty of murder rather than manslaughter was the manner in which national debt was reported in the public sphere. Only a part of the balance sheet was allowed to be discussed. There is no way in hell that it was possible for such a massive campaign of disinformation to be mounted without the active support of a large number of people at the top level of society. No one can be reasonably expected to believe that by presenting such a grossly slanted view of economic information people in top positions were unaware that they were involved in a massive deception.

A democratic society can not function properly when the population is being deliberately decieved. In the sphere of economics alone this disception has been so vast that resonable people should come to the conclusion that the entire political system is no longer legitimate.

Then when we add all of the other massive historical and sociological frauds a reasonable person should come to the conclusion that the system has been deligitamatized many times over.

Of course when you have many powerful people committing a massive fraud one could reasonable expect that these people will make efforts to muddy the waters. To muddy the waters first about whether or not a crime is being committed in the first place. Second to muddy the waters about who the victims are. Third to muddy the waters about the damages that have been done. Fourth to muddy the waters about how to repair the damages. Fifth to muddy the waters about the costs to repair the damages.

Three of you. Very good, Hermann. Yes, Krugman did support the Greeks against the Troika, but you didn’t have to be a progressive economist to do that. You may be right that he enjoys his social status to much to risk it. I think, though, that he could likely get away with it.

Some members of the Eurogroup were unhappy with decisions to ‘punish’ Greece, accroding to Varoufakis, but the policies were pushed hard by Schaeuble and to a certain extent the IMF. Those times the IMF demurred over the terrible terms, was this PR? As for the Dutch, after the war they decided to tie their economic fortunes to Germany.

My late former father-in-law sold Dutch manufactured machines to the Germans. He, and others, had to hide from the Nazis throughout the war. My mother-in-law never recovered from what the Nazis did in Holland and hated Germans, with two or three exceptions, until the day she died. However, Dutch attitudes to the Germans are complex. For instance, foreign Dutch TV programs are often subtitled while German ones of foreign origin (that the Dutch can get) are often dubbed and the Dutch I knew, and still know, laughed about this. But, until quite recently, the Dutch school system made the pupils learn five foreign languages. They have since reduced this to three. Hence, they could read the subtitles.

I can give an example where English subtitling was inaccurate and, thereby, seriously misleading. It occurs in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist. Near the end of the film, the piano player was asked by a German army officer what he does. He replies: Ich war, nein, ich bin ein pianist. The subtitles left out the reference to the present, IIRC, psychologically an essential part of the story and the pianist’s journey to his new life that awaited him. Subtitles are not always a superior format. (The pianist’s name, again IIRC, was Spielman, a play on words by Polanski possibly.) Perhaps the Dutch I know were using it as some kind of displacement. Sadly, my German has deteriorated since then.

When I lived in Germany some years ago, Hermann, I used to watch a German stand up comic on TV who, even to me, was hilarious. I can’t remember his name and I never got all his humor or the subtle nuances, as you can imagine. I was told that he was the funniest comic in Germany; at least, he was to the people I knew. I have never, however, to my knowledge met anyone from the elite, either in Germany or Holland.

HermannTheGerman:- ‘She describes them as “still a nation of pirates”, “swamp germans” or “cutthroats with a smile”‘

To be scrupulously fair, I imagine not a few non-Brits might apply analogous descriptions to us Brits. Especially the City of London.

All Thatcher’s fault of course. Before her time the City was populated exclusively by “gentlemen”. Then came “The Big Bang” whereupon they dropped all pretence and unashamedly hoisted the jolly roger. Since when they haven’t bothered to even try to disguise what they really are – conscienceless parasites pure and simple.

But we Brits learned it all from the Dutch, so they must be worse than us. (But didn’t they learn it from the Italians…?)

As much as I enjoy reading Bill’s posts, every time his topic is Germany there is a obvious hatred which permeates his writing that leaves a sour taste. There is quite a lot of misdirection and misinformation bundled together in Bill’s today post, and alas I have no time to go through it point by point, but there are a couple of truly crass errors that absolutely need to be addressed.

First off, to talk about the last two quarters and “forget” to mention WLTP is disingenuous at best. The german car industry was hit hard by their partly home made, partly EU-made problem of not being able to certify entire model lines in time for the new test cycle. The demand for the cars is still there, which is why waiting times for some models shoot up to one year and more, but they would have had to build them and store them somewhere (at significant costs, as VW discovered with the BER airport storage), because they were not allowed to sell them until certified. So obviously a lot of them decided to significantly cut back production or even turn off manufacturing lines & plants for weeks at a time, to avoid building up inventory.

This one-time effect alone made a difference of roughly 0.3% of the GDP in the 3rd quarter, so if you eliminate it, Germany would have had a (slight) growth quarter instead of a contraction. And the effects of the WLTP problem were felt well into the 4th quarter.

Now obviously, it would be foolish to say that the current growth is robust, but it’s far too soon to claim it hit a wall. Or if it did, I am guessing it hit the same wall that everybody else has or will in the next period, once the turbulence of tariff wars, Brexit chaos, Chinas credit bubble and so on get really going.

Bill writes, in regarding to his first graph:

“First, you can see the suppression of domestic demand began soon after the inception of the euro – the Hartz devastation (see below).”

That’s unfortunately nonsense, or at least the second part of is. As Bill himself writes later, the Hartz “devastation” began in 2003, and really got into swing at the beginning of 2005 with the BGBl. I S. 2954. But his first graph clearly shows that the domestic demand dropped or flatlined between 2000 and 2005, and quite clearly went back on a growth track after 2005.

So obviously this particular evolution had little to do with the Hartz “devastation” – or at most what one could read from the graph is that the “devastation” paved the way for the growth in domestic consumption. But – as we know – correlation is not causation.

Bill writes, on possible solutions:

“It also could stimulate public spending – say, to start the long process of restoring quality to its public infrastructure which has been seriously degraded by the austerity mentality of successive German governments.”

Dunno, as soon as one leaves Germany in pretty much every direction (with a tiny exception on the south border to Switzerland), one becomes very rapidly quite a longing for that “seriously degraded” infrastructure, and wishes to go back as soon as possible to using it. Not that it is perfect (which infrastructure is?), but compared to most of western Europe, it’s (on average) more that acceptable, especially given the fact that it is the main transit country of almost all west-east logistic transports, which brings a massively increased wear and tear on the roads & rail.

What people simply forget when they crow about “crumbling” bridges is that Germany has had a very one-sided and enormous infrastructure built-up project in East Germany for the last 30 years. I doubt that there are that many precedents (China and post-war times excepted) of building or repairing so much infrastructure in such a short period of time. This obviously led to a not so pleasant side effect, which is that necessary repair and upgrade projects of infrastructure in West Germany – in particular in the areas which aren’t that prosperous – took a (slight) back seat. So, obviously, there are areas where investment is needed, but it’s not so much an artifact of the federal government not investing but more of the federal government investing with a geographical bias.

That aside, even if the government were to invest more in infrastructure projects, there is currently absolutely no slack left in the market – as anyone who has planned anything that has to do with building projects in the last couple of years, be it public or private, small or large, can tell you, there is very little spare capacity left. It can easily happen that you receive no offers whatsoever on public tenders, or that – if you do – you get a “f**k you” offer going 200% or even 300% over the budgeted costs.

Surely no one can seriously consider creating even more demand in the construction sector – that would be utter insanity.

Bill writes, about his pet topic of mini-jobs:

“The proportion has been fairly steady since late 2007 after a rapid increase in the earlier years of the scheme. However, it is starting to rise again, albeit slowly.”

That’s not what the graph shows, quite the contrary, and the misdirection is even more obvious once you look at the actual statistics: the (absolute) number of people only employed in mini-jobs is on a downward trajectory since at least 2014. The only reason why the totals still keep constant or grow slightly (again, in absolute terms) is that there are many who work regularly and take an *additional* mini-job.

Now, the statistics on why that is are murky – the left are convinced it’s because people can’t make do with one wage, the reality paints a more subtle picture, with many doing the “mini-job” thing because they are for instance pensioned, but want to work, and at the same time avoid getting hit by a tax increase if they were to take a regular job.

And not to forget: Germany has imported over a million “refugees” in the last three years, which currently have little chance of getting regular jobs: their education, skills and language knowledge pretty much guarantees that the only way many of them will get a “foot in the door” when it comes to work are such mini-jobs. Again: something only somebody interested in misdirection would leave out when it comes to the analysis of the german job market.

Apologies: I misspelled the character’s name in Polanski’s film. It is Szpilman, as he was Polish. I used one of the German spellings.

@HermannTheGerman

“Full disclosure: the PK column was for a long time my go to source for insight on economics so I like to think of it as a sort of a first step towards leaving the mainstream.”

Yes, that’s how I and others I know have used — and valued — Krugman’s columns over the years. I am grateful that he has attacked the “deficit scolds” and the “austerians” on so many occasions.

Krugman and MMTers have been arguing with each other for so many years that the argument has gotten personal on both sides, often obscuring areas of agreement and exaggerating areas of disagreement.

@larry

Indeed, the relationship between Dutch and Germans is as complicated as that of many siblings. For us “outsiders” (despite my screen name I see myself as such) the seem so similar in so many ways, but history has left its marks and they are not likely to vanish anytime soon.

It’s a shame you forgot the name of that German comedian (an oxymoron?), though I have my reservations about what a country that has a fixation on “Dinner for one” finds funny (thanks for that reference @Simon Cohen).

Hermann, Perhaps I am imputing too much to Krugman but perhaps there is a sense in which Taxes ‘pay’ for things in the sense that the Taxes open up fiscal space for the Government to mobilise resources.

Did he mean it in this sense rather than the literal ‘accounting’ sense which gives us the impression the Government spends the same financial assets rather than destroying them.

I’ve not read the article though!

@Simon Cohen

Simon, I’m not entirely sure, either. To me it reads as if he is aware (and shocked and disgusted that you thought otherwise) of the government not having to actually “wait” for tax revenues or else “print” new money in order to spend, but that without offseting that spending with at least the promise of revenues, his doomsday scenario of inflation, high interests and crowding out will occur. In a sense, it’s like saying that just because you can spend without taxing, it doesn’t mean you should.

Your wording using “fiscal space” is to close to a financial constraint to my liking. A constraint we know doesn’t exist. Now, if it is more of a political argument because you know you need to at least pretend “fiscal discipline”, that’s fine by me. However, I don’t think this is what Krugman meant and why I’d like someone competent to adress his piece.

Cheers!

RobertH. Businessmen as malign agents, acting purposefully to harm. No. The greed and selfishness, self-interest is so ingrained. A great businessman thinks only to accumulate. He’ll lie, steal and kill. His thinking is only more, more and more, to take, to win. William Cay Johnston has said that Trump has been in approximately 4500 civil suits so far. That’s they story of someone who will lie, steal, defraud. The only things that matters is “will it profit me?” The people who lust for wealth and power will compromise anyone and anything. The lust generates socio-pathic trends. Moral leadership, the bounds of acceptable practice, need to be set by people who don’t live by those lusts. Unfortunately, wealth and power enable it to acquire more, and are the most able to propagandize and manipulate.

Hermann, Brian Romanchuck has a good response to the Krugman piece you mention. At Bond Economics titled “Functional Finance Versus New Keynesian Economics, Krugman Edition “. I will try to post a link.

http://www.bondeconomics.com/2019/02/functional-finance-versus-new-keynesian.html

When are other countries going to take Germany to task for the mercantilist acts of “warfare by other means” being perpetrated upon German labour and their own populations?

Simon, Krugman’s article is, imo, a mess (the heterodoxy one). He doesn’t understand MMT at all. He never has and the impression I have always had is that he doesn’t think he needs to. Thsi is because he thinks he *knows*. It is impossible to believe any of it. In the preceding post, related to it, he displays a pic of Lerner’s 1972 book, Flation, not his earlier work. This is poor. In this post, Krugman used the relation between r and g, an important relation for Piketty, whose book is filled with neoliberal argumentation, even though the data is good. Neither the heterodoxy nor the fuctional finance posts are worth reading, I don’t think.

Larry, I’ve got a copy of Lerner’s ‘Flation.’ I read it some time ago but got the impression that he was in a more ‘mainstream’ mode when he wrote it-is this true in your view? I can’t remember much about it now, unfortunately but I think I recall Bill writing in a post that Lerner became more mainstream due to his increased fear of inflation towards the end of his life.

Simon, you are right. This particular book is more mainstream than his earlier work. And Bill did mention this in a recent post. But Krugman’s treatment of Lerner’s ideas is, in my view, pretty inexcusable, and cavalier, a criticism he levels at Lerner. I also read this book a while ago.

Dear Andrei (at 2019/02/19 at 11:10 pm)

There is no hatred for Germans in my writing.

And the blog post yesterday was rather factual.

1. Yes, the divergence between domestic demand and GDP growth occurred before the Hartz changes. There was a major recession in Germany just prior to the Hartz period, which killed growth. I have written about that before. It is famous because Germany was the first nation (with France, also enduring a recession) that breached the Stability and Growth Pact and then bullied Brussels into altering the rules rather than being sanctioned for the breach.

2. Hartz then consolidated that divergence until the current day by suppressing workers’ pay and creating millions of low pay work.

3. I didn’t mention WLTP – but I cannot include everything. I did mention Trump and China and the UK as factors causing German exports to decline. I could have written a whole post about the woes of the German car industry including its deliberate fraud concerning environmental standards which have impacted on its current export performance. But that would have been a diversion. The point was that being so reliant on exports renders an economy susceptible to all manner of shifts in spending patterns and regulative changes.

4. Growth hits the wall when we see a September-quarter of -0.2 per cent and a December-quarter of zero growth. Most recessions or near recessions are short affairs anyway. For various reasons, German GDP growth has hit a stop (wall, whatever you want to call it). History suggests it will rebound rather quickly. What is the point you want to make

here?

5. German reunification was a major disruption and I have acknowledged that in the past and devote considerable time to it in my 2015 book Eurozone Dystopia. But to say there is no slack in the labour market is to deny the massive underemployment, partly manifest in the 20 per cent of the workforce engaged in MiniJobs.

Anticipating the infrastructure deficit that arose as a result of reunification, it would have been more sensible to set up skill development than to shunt people into MiniJobs.

6.The MiniJobs graph is not detailed enough (scale) to fully appreciate the recent movements. Over 2018, the total number of MiniJobs were March-quarter 7,388,712 (18.3%); June-quarter 7,527,982 (18.7%); September-quarter 7,548,065 (18.5%) and December-quarter 7,563,100 (no proportion because latest labour force data is not available yet).

The number is rising. And the trend in the proportion is rising (very slowly). That is an accurate statement.

7. The blog post was not a micro analysis of the German labour market. It was about the imbalance in the growth strategy. A detailed analysis of demographic patterns of involvement in various types of labour force engagement was not the focus, notwithstanding the interest.

Thanks for providing additional information in a considered comment.

It doesn’t negate what I wrote. Just enriches it.

best wishes

bill

The question of intent versus incompetence is interesting.

It is a puzzle when you try to reduce political economy to economics.

When you ignore power relationships.

Beliefs bend to interests.Medieval kings convert to Christianity and become gods

representatives on earth.Many are truly devout.

Many a wealthy powerful man are true believers .Just so for the new faith of neo liberalism.

Friedman ,Hayek even Aryan Rand are amongst the beloved prophets.

Entitlement and wishful thinking shape belief.

Now you can appeal to reason and say that a falling wage share undermines economic

growth in general but wealth like everything else is relative.As the other monetary

sovereign Mithcell Roger says it is all about the gap .The victory of profits over wages

is the intention , gap psychology.

The separation of intent and competence is an illusion.

@ Jerry Brown

Thanks for the link!

for Kevin Harding (11:51)

The seperation of intent and consequence is an illusion. That sounds like Buddha himself speaking.

I guess that I consider this question important though devicive. First of all when the word conspiracy gets mentioned half of the audiance has been trained to automatically tune out.

So as I mentioned it seems on one hand that a person should down play this aspect as for most people they can not do anything about the conspiracy in the first place. They are only capable of fighting one bad idea at a time as the bad ideas get introduced. On the other hand I have an impression that when people are convinced that something bad is being done deliberately rather than as a result of stupidity they have an even greater sense of moral outrage. This greater sense of moral outrage could lead to more active opposition among the population.

There is also theoretically the question of accountabilty. If it were possible to hold people accounable for their destructive political behavior those doing the accounting would have to decide whether to forgive the offenders because they were stupid which we all are at least at times. Therefore based upon the principle of the golden rule we should forgiving their stupidity would be reasonable. The accused could be Forgiven because they were insane and therefore not morally cupable. The accused could also be punished. If those who have waged wars of aggression and brought humanity to the edge of extinction have done so with intent, the punishment could be mild and symbolic. The punishment could on the other hand fit the crime and be really really harsh.

I myself would chose the latter. I doubt that humanity has a long future left. But if humanity did have a future the positions that those I accuse of crimes found themselves in made it possible for them to act in ways in which there would be little possibility that they would ever be held accountable for their behavior. The costs risks benifits formulas that they were tempted with corrupted them. Therefore it seems to me that the risks part of that equation needs to be changed. Since the chance that they will be held accountable is so low the potential punishment that they will recieve should they face prosecution needs to be extra ordinarily high. The punishments that were given to the Nazis did not deter them at all.

From that I draw the conclusion that death by hanging or firing squad is insufficient. Some might argue that since we are all sinners no one has a right to dish out a harsh punishment.

I find that a totally unconvincing arguement. That would be like saying a car thief has no right to be a juror or executioner for a rapist or murderer.

@Bill:

You write:

Growth hits the wall when we see a September-quarter of -0.2 per cent and a December-quarter of zero growth. Most recessions or near recessions are short affairs anyway. For various reasons, German GDP growth has hit a stop (wall, whatever you want to call it). History suggests it will rebound rather quickly. What is the point you want to make here?

The point I am making is that you can’t simply make sweeping claims like “German growth strategy falters” based on two quarters which were quite likely strongly influenced by a one-time effect like the WLTP delay. You *might* be right, and the German growth strategy *might* be faltering, but there is no data that demonstrates this to be true right now. If let’s say across the whole CY2019 Germany keeps growing below average compared to similar economies (or shrinking while everybody else is stagnating or growing), then (and only then) you might have an argument.

You write further:

But to say there is no slack in the labour market is to deny the massive underemployment, partly manifest in the 20 per cent of the workforce engaged in MiniJobs.

I said there is no slack in the construction market, not in the general labour market. Two very different things, which make your suggestions about more infrastructure investment questionable at best. As the recent IAB study pointedly noted, the moving average of vacancy periods for open job offerings in construction lies at 141 days, significantly over the 107 average across all job openings. Some construction related areas, especially the areas which are served by tradesmen like for instance plumbing & heating, have a vacancy period of over 180 days!

Obviously there is currently very little leeway for construction companies to significantly increase their capacities, so there is equally little leeway for the government to begin infrastructure projects. And equally obviously there is no way to snap your fingers and hope that the jobless or the mini-jobbers will transform into construction workers overnight.

Also, there are no 20 percent of the workforce engaged in mini-jobs (see below).

You write further:

The MiniJobs graph is not detailed enough (scale) to fully appreciate the recent movements. Over 2018, the total number of MiniJobs were March-quarter 7,388,712 (18.3%); June-quarter 7,527,982 (18.7%); September-quarter 7,548,065 (18.5%) and December-quarter 7,563,100 (no proportion because latest labour force data is not available yet). The number is rising. And the trend in the proportion is rising (very slowly). That is an accurate statement.

But it is not accurate, for a simple reason: your total number includes workers that have a mini-job, but also have a normal job as well! So you are counting them twice, when you calculate the percentages. The real numbers (including the last three months available, as well as year over year comparisons for November) are as follows:

Employees in regular jobs:

11.2018: 33.495.900

10.2018: 33.477.800

09.2018: 33.418.700

11.2017: 32.829.600

Employees *only* employed in mini-jobs:

11.2018: 4.651.100

10.2018: 4.629.300

09.2018: 4.635.700

11.2017: 4.719.900

Employees with normal jobs, who *also* have a mini-job as a side job:

11.2018: 2.928.800

10.2018: 2.917.100

09.2018: 2.909.300

11.2017: 2.794.800

As one can clearly see, the absolute numbers of employees with regular jobs is rapidly increasing (2% year over year for November 2018), while at the same time the number of pure mini-jobbers is rapidly decreasing (-1,5% YOY). The sole reason why the total number of employees with a mini-job is slightly increasing (+0,9% YOY) is because of the rapid increase in the segment of those that have a regular job, and work on the side in a mini-job (+4,8% YOY).

Now, as said, one could spin this as proving that regular jobs are no longer providing enough food on the table for workers in Germany (and many here do jump to this obvious, but likely wrong conclusion), but the various surveys that try to find out the motivation behind mini-jobs as a side job paint a far more diverse picture.

It is pretty much clear that a significant proportion of those working mini-jobs as a side job make this per choice, because they simply don’t want to work more, or because they don’t want to work more and pay sigificantly increased taxes.

Whatsmore, even for those that actually *only* have a mini-job there are various studies that show that a significant proportion also does this by choice, and wouldn’t actually be available to work in a regular job. So you can’t simply count them as being underemployed, at least not without further nuancing.

HermannTheGerman:- “I’ll let the historians sort out whether the death of Europe was a murder or manslaughter”.

Yok:- “Businessmen as malign agents, acting purposefully to harm. No. The greed and selfishness, self-interest is so ingrained. A great businessman thinks only to accumulate. He’ll lie, steal and kill. His thinking is only more, more and more, to take, to win.”

The explanation is that most leading politicians like Merkel are not evil or ignorant but are really just figureheads and public spokespersons for political groupings that are indeed controlled by powerful vested interests that ‘think only to accumulate’ – regardless of the cost to citizens or others outside their clique, and that are centred on business interests that control or own the most wealth. In Germany’s case its the finance sector and the major manufacturing corporations. In Australia’s case its mainly the finance and mining sectors supported by real estate speculation and gambling. For the US its the finance sector, the defence/industrial/security sector and the major corporations in general.

As Bill has often mentioned the decisive turning point between the power balance between citizens and capital turning in favour of capital globally was the ‘Powell memorandum’. This fight back by capital which picked up momentum back then went on to impose monetarism and neoliberalism and took over effective control of the democratic, legislative, governmental, mass media and even academic processes and institutions in all the areas that mattered to capital.

Can politicians like Jeremy Corbyn or Bernie Sanders and their political bases roll back a thoroughly corrupted political process that is controlled by such greed obsessed, amoral, cruel and powerful interests, to something like what existed in the mid 1970’s? Much of the electorates of each nation don’t even know they are being screwed and even fewer feel compelled to fight for change.

The Democratic Party in the US is just the first stage of the fight for the US and it has not gone well so far for Bernie and his progressive movement but at least the Green New Deal and even financing it by harnessing fiscal policy are being dicussed.

https://popularresistance.org/the-movement-and-the-2020-elections/

I hope Curt’s pessimism, or realism, does not come to pass.

Curt Kastens:- “I doubt that humanity has a long future left.”

curt i said the separation of intent and competence is an illusion .

Not consequence.In the context of the failures of the neo liberal project.

There is no need for a conspiracy to explain why wealthy powerful people

want to keep their wealth and power .

Just because it is in their material interests does not make them hypocrites

entitlement and wishful thinking are powerful psychological drivers and their beliefs

may often be earnestly felt.

Indeed wishful thinking is something none of us can escape.

Kevin, Yes, Sorry bad proof reading on my part. Incontenance is what I meant to write. my thinking and my writing were in different gears.

Andreas, Thank you.

I’m gratified that my original question (“is Germany’s “beggar-my-neighbour” (aka mercantilist) policy consciously and deliberately malign in intent?”) triggered such an impressive debate as this one.

Summing up (which I hope won’t seem impertinent), the balance of opinion seems to be that the answer is “no, but…”.

Germany is not acquitted of all moral responsibility for the consequences of her actions merely on the grounds that her stateswomen and -men may not (did not?) foresee or intend (all? any?) of them.

On a side-note (and with apologies for going off-topic), Andreas Bimba’s mention of the Powell Memorandum prompts me to observe that the position of the USA is qualitatively different by virtue of its being a military super-power. Yes, in the USA just as in other “advanced” economies big business consciously mounted and systematically executed a no-holds-barred counterattack aimed at reversing all of the gains made by labour over the preceding decades. It led, and its counterparts in the other countries followed suit. Monetarist and neoliberal doctrines were the weapons of choice and boy! how effective they’ve been!

But side by side with that, and in an altogether different league than us second-class powers (being flattering), the USA has ever since WW II been bent upon attaining and maintaining global hegemony. In the initial phase it saw itself as battling toe-to-toe for supremacy with the sole contender in the heavyweight class the Soviet Union, the USA itself as the champion of freedom having sole claim to virtue and the end therefore justifying the means (the adversary being evil incarnate – which indeed, in the shape of stalinism, it was).

So *of course*, just as in every Western, the “goodies” had to win – and they did. But the battle didn’t end there – far from it. The same “conquest by other means than war” – as Michael Hudson so eloquently describes it – went merrily on without even pausing for breath, with American corporations, the IMF/World Bank axis, any and all other agencies which could be suborned or threatened into doing so serving as auxiliaries in the USA’s project for – sorry about the cliché – unfettered world domination. Ostensibly “only” economic yes, but actually as the means for geopolitical domination, backed whenever and wherever necessary by the ever-present potential for the use of overwhelming military might. “Gunboat diplomacy” reborn.

The same cannot even remotely be held to be true of us others, except insofar as by being willing to be lackeys of the USA we choose to make ourselves complicit. I’m ashamed to say that that is what my own country has all too often been guilty of (and is, right now, in relation to Venezuela). But are we the only ones?

If democracy is stolen from the people and replaced with brutal plutocratic feudalism then I suppose we will have to eat those of the rich that are devoid of compassion and their accomplices. Or if that is too distasteful, they could possibly be used to add protein to fish pellets? Otherwise we instead will be on the menu or inside those pellets.