I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

The impact of government on reserve dynamics …

This blog is based on some research on Japan I have been doing as a precursor to a book contract I am working on which will be about developing a progressive macroeconomic narrative – a sort of cookbook for progressives to enable them to challenge the major myths that are perpetuated by neo-liberals. These myths lead to the imposition of voluntary constraints on the government capacity to achieve and sustain full employment. Some of the underlying dynamics of the system which expose these constraints for what they are – an ideological distaste for fiscal intervention – are still not well understood though. Here is some more on that theme.

I was reading an interesting paper the other day – A Guide to Bank of Japan’s Market Operations – by an officer from the Bank of Japan. It is a translated version of the original (dated 2000) and is relatively faithful to the original meaning (sometimes these translations are not!). While some of the discussion is arcane, in general it is a very good descriptive account of the way banking operations work in Japan – that is, the interactions between the Bank of Japan (central bank) and the commercial (private) banks. I recommend it to those who have insomnia … or those who are like me and enjoy reading about the nitty gritty of how systems work rather than how our Matlab models might assume they work.

The BOJ paper (pp.2-3) defines the monetary policy variable as:

… the Bank chooses the uncollateralized overnight call rate as the operating target. There are three reasons for this. First, the overnight call rate is relatively easier for a central bank to control. In the uncollateralized call market, banks and other financial institutions trade overnight funds to make final adjustments of their daily cash positions. Transactions in this market, therefore, reflect the strength of demand for liquidity in the market as a whole. In addition, the rate in this market clearly reflects the balance between the supply and demand of funds … It is therefore relatively easy for the Bank to control the overnight rate by adjusting funds supply.

So you learn that it is the liquidity of the system that influences the overnight call rate and so the BOJ has to influence that liquidity via vertical transactions with the non-government sector – see Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 and Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 for more discussion of this.

What factors determine the supply of and demand for funds and what exactly are “funds”? The BOJ paper (pp.4-5) defines these funds in this way:

Funds to be adjusted through market operations are the current account balances at the Bank held by private financial institutions (hereafter, CABs), in other words, the balances of financial institutions’ deposits with the Bank. The majority of CABs is reserve balances, i.e., reserve-deposit balances held at the Bank by depository institutions to fulfill legal requirements. The rest includes balances maintained to meet payment and settlement needs by depository institutions as well as nondepository institutions, such as securities companies, securities finance companies, and tanshi companies (money market brokers-cum-dealers) … [the] …”demand for funds” will refer to demand for CABs as a whole, which include those of both depository and nondepository institutions. On the other hand, unless otherwise noted, “supply of funds” will refer to CABs, which are supplied through the Bank’s operations.

So in the main we are talking about reserve balances held at the central bank to facilitate the clearing and payments system and provide some prudential security (where formal reserve requirements are in place).

The BOJ paper then considers the reserve adjustments that occur between private financial institutions (the horizontal transactions). So private banks are involved in a multitude of transactions each day which require a smoothly functioning payments system.

These daily business operations cause day-today fluctuations in the CABs held by individual institutions. Any resulting surplus/shortage in CABs is adjusted between private financial institutions in the money market, especially in the call market where funds are delivered on the day of the contract.

So these transactions are made between the reserve accounts held at the BOJ. The example given is that Bank A currently has a surplus of reserves (1 billion yen) while Bank B has a shortage of the same amount. The two banks then offset this surplus/shortage by A lending to B. This is the way in which the interbank market operates.

However, the author then recognises that these horizontal transactions do not create/destroy any net overal positions (financial assets) in the funds market. The private banks can shuffle the excess reserves around each other via the interbank market but cannot change the overall level of bank reserves.

So the BOJ paper (p.6) goes on to say that:

… On a day when CABs … [bank reserves} … as a whole are sufficient to meet demand for funds, private financial institutions can offset each others’ individual CAB surplus/shortage through the call market. In this case, there is no need for the Bank … [that is, the BOJ] … to intervene. However, when exogenous factors – such as flows in banknotes and treasury funds – cause private financial institutions’ CABs as a whole to decrease (increase), overall demand for funds cannot be exactly met even after adjustments between institutions. As a result, an upward (downward) pressure will be exerted on the overnight rate. If the Bank increases (decreases) the supply of funds, this upward (downward) pressure is alleviated and a rise (decline) in the rate is thus prevented. The Bank adjusts the amount of funds supply through market operations, taking into consideration the developments in demand for funds as well as factors affecting the overall provision of CABs; this is the basic mechanism for the Bank to guide the overnight call rate.

There is a lot to learn from reading that statement carefully. Some days as a result of “exogenous” factors such as flows of treasury funds (that is, changes in the fiscal position of the government) there will be either an overall surplus or overall deficit of reserves in the system.

For example, when net government spending is positive (that is, a budget deficit), reserves will be increasing beyond the “demand for funds” by the private banks. That is, there will be excess reserves – supply is greater than demand. The result is that there will be downward pressure on the overnight rate. This is because the private banks in excess will try to place the funds on the interbank market given in Japan (at that time – 2000) no interest rate was paid on excess reserves. The competition between the excess reserve banks to loan those funds out drives the overnight rate down. So effectively, the BOJ’s target rate becomes irrelevant at the short-end of the yield curve (the structure of interest rates from call to long period).

In this case, the BOJ has to “adjust the amount of funds supply through market operations”, which means it sells government bonds to the private banks to soak up or drain the excess reserves and provide them with an interest-bearing asset in place of the zero interest-bearing reserves.

So the government (via the BOJ) looks to be borrowing. A neo-liberal constructs this backwards – they see the deficits and the borrowing – liken it to a household transaction where that entity has to fund all its spending in advance – and conclude that the debt sales to the private sector were raising funds that were then used to prosecute the net spending via fiscal policy. So debt issuance (borrowing) is an integral part of running deficits.

The logic is however all backwards. The BOJ paper is very clear. Exogenous factors (like deficit spending) impact on the amount of reserves in the banking system. If nothing is done about the reserve excess that emerges defined as supply being greater than demand, the overnight interest rate drops and the BOJ loses control of its interest rate target (unless it is zero) as the interbank rate heads south to zero.

Note that we are in the domain of monetary policy. The fiscal policy decisions have been made and executed – sovereign governments spend by crediting bank accounts or issuing cheques which end up in bank accounts. These actions add to reserves. If net spending is positive then bank reserves will rise and vice versa (if tax receipts are greater than government spending).

In the case of a budget surplus, bank reserves are destroyed and vanish from the system. The private sector feel the impact of the surplus because there is less income to spend and less employment and less public infrastructure provision and more. But the banking system just notes a decline in reserves. The surpluses do not “go anywhere” – into storage for later use. The transactions are recorded electronically, the bank reserves adjusted and everyone goes home for the night.

Thus borrowing is about monetary policy. This is a major flaw in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks which always have the borrowing in the fiscal policy chapter based on the flawed – backwards logic that the debt funds spending.

Public borrowing is a monetary policy act because it is one of the means that central bank can use to drain excess bank reserves which stops interbank competition undermining its interest rate target each day. It has nothing at all to do with funding the government spending. That is done and dusted! But the net spending (positive or negative) impacts on the bank reserves and requires a monetary policy response.

It couldn’t be clearer than that. Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates. Financial crowding out does not occur via budget deficits.

Contrast that reality (derived from a firm operational understanding of the way the system works) to the sort of mainstream logic that gets fed to student in economics courses. For example, in discussing a net increase in government spending, well-known text-book author Greg Mankiw in the Essentials of Economics writes (pp.559-560):

While an increase in government purchases stimulates aggregate demand for goods and services, it also causes the interest rate to rise, which reduces investment spending and puts downwards pressure on aggregate demand. The reduction in aggregate demand that results when a fiscal expansion raises the interest rate is called the crowding-out effect (emphasis in original).

That is what we are up against.

Anyway, back to the BOJ paper. It continues to clarify the effect on treasury operations on bank reserves – so the impact of vertical transactions. We read on pages 9-10 in the context of exogenous factors that impact on CABs (reserves) that the “flow of treasury funds between private financial institutions and the government (treasury funds factors)” are very important:

The treasury balance at the Bank decreases when the government debits its account at the Bank and credits the accounts of private financial institutions for, e.g., the payment of pensions to households or that for public works to firms. Flows of treasury funds between the government and private financial institutions thus take place through their accounts at the Bank. Therefore, a decline in the treasury balance is accompanied by an increase in CABs, and is a funds (CAB)-surplus factor. On the other hand, an increase in the treasury balance, which occurs when the government receives funds from private financial institutions in the process of collecting funds such as taxes from households and firms, is a funds (CAB)-shortage factor.

This is a fundamental part of the reserve accounting that underpins modern monetary theory. Government spends by crediting bank accounts which adds to reserves. Taxation is accomplished by debiting bank accounts which reduce reserves but provide the government with no extra capacity to spend.

The vertical transactions (between government and non-government) lead to changes in the net financial assets held in the non-government sector though. A “decline in the treasury balance” (held at the central bank on behalf of the treasury for accounting purposes) adds to private bank reserves – a “funds (CAB)-surplus factor”. Whereas, if the government runs a surplus on any day (the treasury balance increases) then this drains reserves – a “funds (CAB)-shortage factor”.

Then the BOJ paper (p.11) provides interesting detail about how the BOJ forecasts the likely treasury operations. It says:

Daily fluctuations in … the treasury balance cause day-to-day shortage/surplus in CABs as a whole. It is therefore necessary for the Bank to forecast as accurately as possible changes in banknotes in circulation and in the treasury balance in determining the size of funds provision through market operations. A projection is first made for the medium term of about three months ahead. This is then revised and refined to projections for a month, a week, and a day ahead. The projection for the day is even revised several times. To ensure high accuracy, the head office and the branches of the Bank gather necessary information from private financial institutions and government agencies on a daily basis. Patterns of CAB surplus/shortage in the past as well as analyses of economic and monetary indicators are also taken into account in making medium-term projections …

For treasury funds, medium-term projections are based on data collected by the Bank about individual government agencies’ schedules for the payment and receipt of funds, as well as on analyses of economic indicators such as firms’ financial statements. Short-term projections are based on the aggregated forecasts of the payment and receipt of treasury funds by government agencies and private financial institutions, which are collected by the Bank.

This gives you an idea of what I mean by the consolidated government sector comprising the central bank and the treasury. They simply have to work together because they both engage in vertical transactions which can create or destroy net financial assets in the non-government sector. Only transactions emanating from the government sector can add or destroy bank reserves. This is a fundamental aspect of modern monetary theory which is misunderstood by mainstream macroeconomists and those who profess debt-deflation theories.

To really understand how the monetary system operates and the reasons for crises, debt build-up, etc you have to start with the government sector’s interaction with the non-government sector. It is the creation and destruction of net financial assets via government net spending that is at the heart of the dynamics of bank reserves. You can say nothing very interesting about the behaviour of private banks until you know how net reserves are created or destroyed.

When is debt toxic?

This also helps us understand the notion of toxic debt better. I often write about the unsustainable nature of an economy that is growing via ever increasing private debt and being fiscally dragged by budget surpluses. This has been the hallmark of the Australian economy since 1996. Debt-deflationists base their entire explication of economic dynamics on the private debt burden without considering as a starting point the interaction between government and non-government.

But one has to be cautious in how we consider private debt and it is here that the debt deflationists are absent.

A solvent debt situation one day becomes a toxic debt situation next day. How come? Clearly, because the person holding the debt becomes unable to service it. Why? They lose their job. Why? The budget deficit is not large enough to sustain the saving desires of the non-government sector.

So the concept of toxic or non-toxic debt becomes heavily conditioned or dependent on the state of fiscal policy and the way net spending impacts on net financial assets in the non-government sector.

Japan as a non-linear dynamic model

A commentator the other day asked me to respond to a statement that Steve Keen had made in some other forum in relation to modern monetary theory. There seems to be a relatively constant desire by readers (given E-mails I receive and comments posted here) to construct a comparison or synthesis between the work of Steve Keen and my own work. The logic of that might be interesting in itself but the urgency has never crossed my mind.

First, I am reluctant to set one blog against another in a personal way.

Second, modern monetary theorists already have developed coherent Minsky-driven analyses of private credit cycles and the instability that they invoke. Randy Wray, after all, was Hyman Minsky’s PhD student! I have also written about this in the 1990s and after and in the early 2000s, one of my PhD student’s completed an excellent thesis on this topic. So those insights are already incorporated into our analysis.

Third, I don’t really see the need to comment on statements made elsewhere which clearly do not reflect an understanding of basic reserve accounting and which are peripheral to the mainstream debate. My target are those that pedal influence.

However, one of the comments provided to me yesterday from Steve fascinated me. It was in relation to the modern monetary view that fiscal expansion can always sustain demand at high employment levels. Steve was purported to have said in relation to this:

Where I am querulous is the sustainability of indefinite government deficits. Point 5 of your 4 points above is that the government now has a debt-servicing obligation to the private buyer of government bonds. Chartalists often argue that this servicing requirement can also be met by issuing further bonds, etc. etc.; I am not convinced on the long-term monetary and productive sector and inflationary consequences of this, and won’t be convinced one way or the other until I’ve put together a dynamic model than encompasses the entire set of processes and their feedbacks.

First, (unfascinating) I have never seen any modern monetary theorist say that debt-servicing requires further debt issuance. It might but paying the interest and the debt back is just a basic crediting of bank accounts and adding to the reserves in the bank system. Most of us would not have any debt issuance in the first place and question the ideological basis of it.

Second, (unfascinating) clearly when growth in nominal aggregate demand outstrips the capacity of the real economy to respond via production then inflation results. Unambigious – we say that all the time. But there is never a question of solvency. If there is inflationary pressures then fiscal policy can fix that too – increase taxes and/or cut spending. But that problem has nothing intrinsic to do with government spending. If there was a private investment boom you could have the same issue. That is just the result of running the economy beyond the real limit. So run it a bit before the real limit!

Third, the final point is the one that fascinated me – the need to “put together a dynamic model than encompasses the entire set of processes and their feedbacks.”

Well, there has already been the ultimate non-linear “dynamic model than encompasses the entire set of processes and their feedbacks” built. I call it Japan others might call it Japan too. In fact, we can all call it Japan.

This real world demonstration of how a fiat monetary system behaves should guide all of us because it demonstrates the veracity of a number of fundamental elements of modern monetary theory and debunks (word not used in any pointed fashion) all of the fundamental elements of mainstream macroeconomics. Debt deflationists are placed somewhere between the two camps – not quite leaving the halls of orthodoxy (noting all the statements about inflationary consequences of public deficits) but not entering the logic and operational reality of modern monetary theory.

You can get Japanese bond issuance data and other data series from Japan Stats.

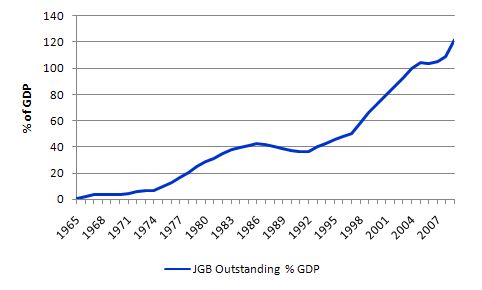

Consider the following chart which shows the evolution of Japanese Government Outstanding Debt as a percentage of GDP. It has ballooned somewhat in recent years and is now 122 per cent of GDP. So that is way beyond what the level of public debt is in Australia and way beyond what it will go over here near over the course of the current deficit cycle.

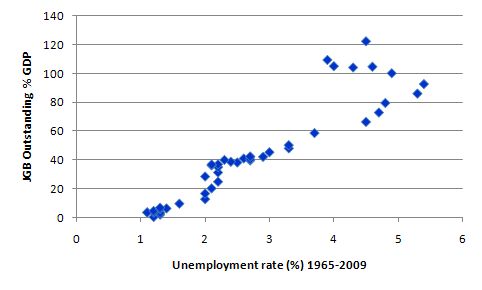

Then consider this graph which shows the unemployment rate (%) on the horizontal axis and Japanese Government Outstanding Debt (% of GDP) on the vertical axis. The link is of-course the deficits that were growing year by year in the late 1990s to put a ceiling under the rising unemployment rate as the Japanese miracle waned.

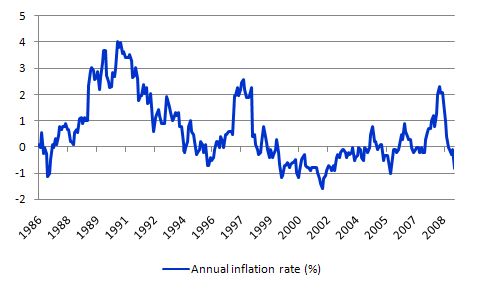

Now consider the two nominal time series that might show signs of instability. First, the annual inflation rate. Clearly, as the deficits were growing year by year, inflation was falling dramatically and deflation became the problem. So there is nothing in Japan’s experience as the second largest economy in the world (at that time) which would lead you to believe that persistently high deficits inevitably cause inflation. It all depends on the conditions.

With huge stocks of idle labour and capacity utilisation low in Australia at present there is no danger of inflation becoming the problem in the medium-term period.

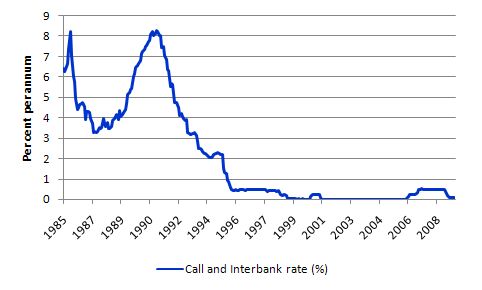

This graph shows the evolution of the call rate (the BOJ target rate) which was also kept the interbank rate in lock step. The monetary system operations outlined in this blog will provide you will all the understanding necessary to appreciate how the BOJ kept the call rate (overnight rate) at zero for so long despite the huge deficits and growing debt issuance.

They simply didn’t drain all the excess reserves (created by the deficits) and let the interbank market compete the rate each day down to zero.

So huge debt build-up, huge deficits, huge public debt-servicing, zero interest rates and price deflation for many years so far.

That is a much better demonstration of how a modern monetary system works than a concocted experiment on a computer with assumed parameters which will produce some lovely graphs.

Conclusion

The BOJ paper I have discussed in this blog is about the operations of the monetary system and the interaction between the central bank, the treasury and the non-government sector (in particular the private banks).

This is where an understanding of the system has to begin with. The government-non-government interactions. A thorough grasp of how net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue enter and leave the non-government sector is an essential precursor to understanding how the non-government sector operates.

Without the former, you miss the essence of the latter.

This Post Has 0 Comments