I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

The myths of the ageing society debate

I am catching up on the mountains of things I have to read. It is a pointless task – the pile rises faster than my eyes can process it. But I try. There was an article in the June 25, 2009 edition of The Economist entitled A slow-burning fuse, which carried the by-line “Age is creeping up on the world, and any moment now it will begin to show. The consequences will be scary”. It definitely might be scary getting old but the discussion that needs to be had is nothing remotely like the discussion that dominates the current policy debate about the ageing society.

The Report starts with this:

STOP thinking for a moment about deep recession, trillion-dollar rescue packages and mounting job losses. Instead, contemplate the prospect of slow growth and low productivity, rising public spending and labour shortages. These are the problems of ageing populations, and if they sound comparatively mild, think again. When the IMF earlier this month calculated the impact of the recent financial crisis, it found that the costs will indeed be huge: the fiscal balances of the G20 advanced countries are likely to deteriorate by eight percentage points of GDP in 2008-09. But the IMF also noted that in the longer term these costs will be dwarfed by age-related spending.

The main hypothesis of the Report is that the slow ageing of the World’s population will have “vast economic, social and political consequences” as labour forces shrink and pensioners rise. You can also hear an interview by Barbara Beck the author of the Special Report.

My first reaction to articles like this before I even think modern money is to conjecture that the threat of unemployment and underemployment as a weapon to discipline the workers and avoid paying them a fair share in productivity growth will be dramatically reduced. Over the last thirty years the distribution of national income in favour of profits has changed significantly (in Australia the wage share has gone from high 50 per cent to low 50 per cent) over the last 25 years.

So as the labour force contracts, firms will have to invest in labour-saving technology which will increase productivity and provide better real wages growth for workers who will have more bargaining power.

My second reaction is that unemployment will be reduced significantly and this might see us return to true full employment.

My third reaction is that the more of us not working means the more of us are playing. Both of these last reactions signal good times to me.

But that is not the way the mainstream thinks.

The two factors that are contributing to the ageing are that people are living longer and having fewer children. The Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (that is, children per woman) has dropped dramatically. It is 2.6 on average globally and “1.6 in rich countries”. The Report notes that the “The UN predicts that by 2050 the global figure will have dropped to just two, so by mid-century the world’s population will begin to level out.”

The other factor to consider is the baby boomer bubble (BBB) that began in 1945 and is now manifesting in increasing retirements. So this bubble will dissipate in around 20 years anyway as we all die.

Interestingly, I read something not long ago that conjectured that the BBs are less happy in retirement than their forebears because they find it harder to live on a diminished income. So this effect will likely see more BBs stay attached to the labour force to supplement their incomes to maintain the rate of growth in gadget purchases.

After providing a pile of not uninteresting demographic information about the developing countries (particularly China), the Report then heads into my territory – macroeconomics. It says:

Macroeconomic theory suggests that the economies of ageing populations are likely to grow more slowly than those of younger ones. As more people retire, and fewer younger ones take their place, the labour force will shrink, so output growth will drop unless productivity increases faster. Since the remaining workers will be older, they may actually be less productive.

Well you don’t need macroeconomic theory to tell you that. First, the labour force will shrink somewhat but then the system cannot provide enough jobs anyway given the failure of governments to use their policy capacities in a sensible way.

Second, it is highly likely that productivity will increase significantly over this period as firms are forced to invest in labour saving technology and also pay higher wages (as the labour force contracts). As noted above the bargaining power will swing towards workers as they become relatively scarce. That will provide a boost to dynamic efficiency and stop the race to the bottom in advanced western countries that have exploited the neo-liberal deregulation agenda to casualise and dumb down their workplaces. This low productivity strategy was never sensible given the population projections.

Third, there is no macroeconomic theory (credible or otherwise) that says that older workers are less productive. Logic says that experience and maturity peak as the worker became older. The old agricultural worker problem where the ageing labourer could not physically maintain the pace of work hardly applies to the majority of workplaces now or over the next 40 years.

Then we get pointy. The Report says:

For the public finances, an ageing population is a huge headache. In countries where public pensions make up the bulk of retirement income, these will either swallow up a much larger share of the budget or they will have to become a lot less generous, which will meet political resistance (and remember that older people are much more inclined to vote than younger ones) … What can be done? As the IMF puts it, “the fiscal impact of the [financial] crisis reinforces the urgency of entitlement reform.” People in rich countries will have to be weaned off the expectation that pensions will become ever more generous and health care ever more all-encompassing. Since they now live so much longer, and mostly in good health, they will have to accept that they must also work for longer and that their pensions will be smaller.

We have to be very careful when we start talking about costs. Here the modern monetary theorist departs from the mainstream which is obsessed with budget numbers on bits of paper. This problem has been at the heart of the fallacies perpetuated by the various governments around the world and international agencies like the IMF.

In Australia, the 2002 Intergenerational Report, which the then government published (as part of the Budget Papers) to provide a justification for their pursuit of budget surpluses, was the first major document to promote the ageing population-fiscal burden nexus.

The IGR (2002: 1) said in relation to the surpluses at that time that

Commonwealth government finances are … [presently] … strong … The Commonwealth Budget recorded an accumulated cash surplus of $23.7 billion from 1997-98 to 2000-01 … During this period, Commonwealth government net debt, already one of the lowest among the industrialised economies, has fallen from $82.9 billion to $39.3 billion.

From a modern monetary perspective, federal finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a “scorekeeping” role. We have learnt that when Government boasts that a $x billion surplus, this is tantamount to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings recorded a decline of $x billion over the same period.

Thus the IGR claim that the Commonwealth “recorded an accumulated cash surplus of $23.7 billion from 1997-98 to 2000-01” is equivalent to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings declined by $23.7 billion over the same period.

Equally, the IRG claim that net debt was very low over some period is equivalent to saying that non-government holdings of government debt fell by the same amount over this period. In other words, private sector wealth was destroyed in order to generate the funds withdrawal that is accounted for as the surplus.

The IGR expressed the standard perspective that the accounting record of surpluses exhibited:

… sound fiscal management … [and] … provided the platform for vigorous, low inflationary growth … generating jobs and higher incomes for Australians.

However, once we appreciate the equivalents noted above we would conclude that this draining of financial equity introduces a deflationary bias that has slowed output and employment growth (keeping unemployment at unnecessarily high levels) and has forced the non-government sector into relying on increasing debt to sustain consumption.

These insights help us understand the errors in the logic underpinning the intergenerational issue in general. Financial commentators often suggest that budget surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy. This has overtones of the regular US debate in relation to their Social Security Trust Fund.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly “stored away” will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the intergenerational debate misconception. While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, it is clear that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

A sovereign government in a fiat monetary system is not financially constrained.

There will never be a squeeze on “taxpayers’ funds” because the taxpayers do not fund “anything”. The concept of the taxpayer funding government spending is misleading. Taxes are paid by debiting accounts of the member commercial banks accounts whereas spending occurs by crediting the same. The notion that “debited funds” have some further use is not applicable.

When taxes are levied the revenue does not go anywhere. The flow of funds is accounted for, but accounting for a surplus that is merely a discretionary net contraction of private liquidity by government does not change the capacity of government to inject future liquidity at any time it chooses.

The standard government budget constraint intertemporal analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is also problematic. The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner. Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures. Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain. Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When modern monetary theorists argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit. We are not advocating unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

This may not coincide with full employment and so it is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that this equality occurs at full employment. Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light. The emphasis on forward planning that has been at the heart of the ageing population debate is sound. We do need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run budget surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

It is clear that the goal should be to maintain efficient and effective medical care systems. Clearly the real health care system matters by which I mean the resources that are employed to deliver the health care services and the research that is done by universities and elsewhere to improve our future health prospects. So real facilities and real know how define the essence of an effective health care system.

Clearly maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. The emphasis in mainstream integeneration debate that we have to lift labour force participation by older workers is sound but contrary to current government policies which reduces job opportunities for older male workers by refusing to deal with the rising unemployment.

Anything that has a positive impact on the dependency ratio is desirable and the best thing for that is ensuring that there is a job available for all those who desire to work.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

But all these issues are really about political choices rather than government finances. The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

Any attempt to link the two via fiscal policy “discipline:, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term. The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such “discipline” reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results.

Clearly surpluses helps control inflation because they act as a deflationary force relying on sustained excess capacity and unemployment to keep prices under control. This type of fiscal “discipline” is also claimed to increase national savings but this equals reduced non-government savings, which arguably is the relevant measure to focus upon.

Dependency in Australia – now to 2050

To give you some idea of the demographic shifts that will occur in Australia, I dug into the ABS modelling data. The following graphs for Australia are all based on the ABS Series A or High Population growth model. It assumes that the total fertility rate will reach 2.0 babies per woman by 2021 and then remain constant, life expectancy at birth will continue to increase until 2056 (reaching 93.9 years for males and 96.1 years for females), Net overseas migration will reach 220,000 by 2011 and then remain constant, and large interstate migration flows. So worst case scenario and probably overly optimistic.

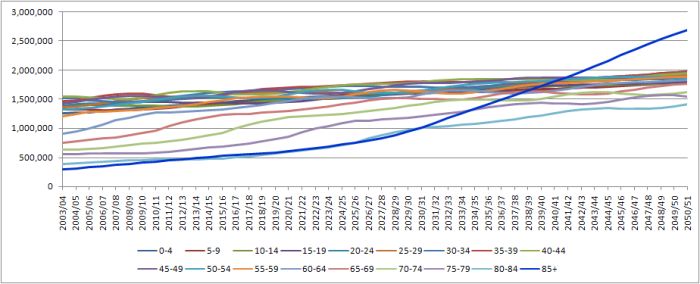

Update – To see how the population by age groups project out to 2050 under these assumptions the following graph is interesting. All the lower lines currently are the older cohorts and over the period shown they become more dominant especially the 85+ (blue line with the rapid upward slope around 2030).

[END OF UPDATE]

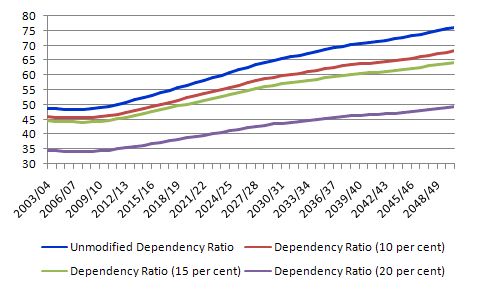

The dependency ratio is normally defined as 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years). Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old. This is what I call the unmodified dependency ratio in the graph below.

The reason that economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions of the government budget constraint. So if the ratio of economically inactive rises compared to economically active, then the economically active will have to pay much higher taxes to support the increased spending. So an increasing dependency ratio is meant to blow the deficit out and lead to escalating debt.

The mainstream approach to the higher dependency ratios is to increase the retirement age (because people live longer they should work longer); redistribute population via migration from younger to older countries; and/or reduce the real value of public entitlements and force increasing numbers to provide retirement income privately.

However, all of these remedies miss the point overall. It is not a financial crisis that beckons but a real one. Are we really saying that there will not be enough real resources available to provide aged-care at an increasing level? That is never the statement made. The worry is always that public outlays will rise because more real resources will be required “in the public sector” than previously.

But as long as these real resources are available there will be no problem.

First, the unmodified dependency ratio as defined is problematic because persons above 65 years of age are increasingly remaining active. This has led to a modification of the formula to take the active older workers (over-65s) out of the numerator and add them to the denominator – these modified computations provide “real dependency ratios”.

The first graph provides some information about this issue because it shows the labour force participation rate of those who are above 65 years of age (a 12-month moving average to disclose trends). It has clearly been rising since 2003 and is now over 10 per cent. It will be expected to rise further in the coming decade as this cohort seek ways to attenuate the wealth losses that the GFC has wrought on their retirement funds. So it is not out of the question that 20 per cent of this group will remain active in the labour force by 2050.

So I computed three real dependency ratios based on a status quote (10 per cent participation by over-65s), 15 per cent average and 20 per cent average over the period between now and 2050. The next graph shows the results. The blue line at the top is the unmodified dependency ratio. The real dependency ratios below it assume increasing participation by the over-65s. If the highest participation is accurate (and it probably won’t be) then the dependency ratio would be 49.3 per cent by 2050 rather than the 45.9 per cent now (with an actual 10 per cent). Even if there is no further rise in participation by the over-65s, the dependency rate would rise from 46 per cent now to 68 per cent by 2050.

Conclusion

The idea that it is necessary for a sovereign government to stockpile financial resources to ensure it can provide services required for an ageing population in the years to come has no application. It is not only invalid to construct the problem as one being the subject of a financial constraint but even if such a stockpile was successfully stored away in a vault somewhere there would be still no guarantee that there would be available real resources in the future.

Discussions about “war chests” completely misunderstand the options available to a sovereign government in a fiat currency economy.

Second, the best thing to do now is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment. This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being practised.

Third, if there are sufficient real resources available in the future then their distribution between competing needs will become a political decision which economists have little to add.

Long-run economic growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future. Principal determinants of long-term growth include the quality and quantity of capital (which increases productivity and allows for higher incomes to be paid) that workers operate with. Strong investment underpins capital formation and depends on the amount of real GDP that is privately saved and ploughed back into infrastructure and capital equipment. Public investment is very significant in establishing complementary infrastructure upon which private investment can deliver returns. A policy environment that stimulates high levels of real capital formation in both the public and private sectors will engender strong economic growth.

If we adequately fund our public universities to conduct more research which will reduce the real resource costs of health care in the future (via discovery) and further improve labour productivity then the real burden on the economy will not be anything like the scenarios being outlined in the “doomsday” reports. But then these reports are really just smokescreens to justify the neo-liberal pursuit of budget surpluses.

As a final irony, for all practical purposes there is no real investment that can be made today that will remain useful 50 years from now apart from education. Unfortunately, tackling the problems of the distant future in terms of current “monetary” considerations which have led to the conclusion that fiscal austerity is needed today to prepare us for the future will actually undermine our future.

The irony is that the pursuit of budget austerity leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

Bill,

Another good post, but I particularly like the following two observations:

Long-run economic growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future.

and

As a final irony, for all practical purposes there is no real investment that can be made today that will remain useful 50 years from now apart from education.

As an aside, I’ve done my best to mess with the ABS assumptions by having three kids.

Bill,

I feel by some of your readings, language and posts that this website is predominately used by the middle aged, so I understand why this article would appeal. This article made me look at the ageing population debate from a whole new perspective. I like the way the article gives rise to the fact that older people are becoming more active and from my perspective most peopole don’t consider this when thinking about an ageing population. I have always just thought people will retire and not contribute much more after that as far as helping the economy. I must ask for the last paragraph, what perspective are you coming from when you say that public universities need more money for research?

Sassi

I agree with most, but not all, of this. Certainly I agree that there is an awful lot of crap talked about the likely economic effects of population aging in Australia – often by people (suprannuation lobbies, I’m looking at you) who have a vested interest in such crap being put about. Whatever the effects of population aging on the pension systems of Italy, etc , they’re irrelevant to us because our system doesn’t work that way.

But I’m far less sanguine about the effects on labour productvity growth than you.

Firstly, it is wishful thinking to deny that, on average, average productivity delcines after middle age in most jobs – certainly in physical jobs, but even in brain work. I know I’m certainly not as quick and flexible as I once was and am already (aged 56) at the age where additional experience gives declining marginal wisdom.

Second, I think technical progress will slow. I grant your point about higher real labour costs stimulating employers to substitute labour-saving capital (you’ve only got to stay at an overstaffed hotel in a low-wage country to see how low labour costs lead to grossly unproductive uses of labour – marginal productivity not only determines wages, it is determined by them). But I think there will be too many old stick-in-the-muds to allow Schumpeterian mechanisms to work. The old are not fond of creative destruction – new labour saving innovations may be thin on the ground. And small-c conservative goverments, unwilling to disturb established rents, will be the norm.

Dear Derrida Derider

I agree that what happens to labour productivity is questionable. But what I think is indisputable is if we continue to under-fund our key research institutions then labour productivity gorwth will be less than it might be. The other point is that the unions are less capable of resisting new technology these days.

But the main point is that it is a real problem not a national government solvency problem.

best wishes

bill

I updated this post on Monday, August 24 to include one further graph showing the movements in age cohorts according to the ABS projections to 2050. I created it the other day but then forgot to include it in the rush to complete the blog.

The section marked Update is about 2/3 into the post at the start of the empirical analysis.

I can reduce the costs and distributional problems of healthcare in about three seconds.

Tie the Medicare provider numbers to a postcode rather than an individual doctor.

Problem solved!

DD-

I totally disagree on labor productivity – in fact, I believe we are on the verge of a quantum leap the likes of which we have never seen before.

Consider: within 10 years (give or take) you will be able to buy a car that drives itself (look up the recent results of the DARPA Grand Challange for a sense of how quickly this tech is advancing.) Now, imagine that generalized to trucking, etc. – it will totally revolutionize transportation, distribution, etc. and make out current attempts at “just in time” manufacturing look feeble.

Also, check out this video, which I found on Slashdot the other day: http://www.hizook.com/blog/2009/08/03/high-speed-robot-hand-demonstrates-dexterity-and-skillful-manipulation The Japanese, who are aging more rapidly than the rest of the world, are taking the lead in all aspects of robotics because they know the workers are not going to be there.

A bit more speculatively, I draw your attention to the developments in the late Robert Bussard’s concept of “polywell fusion” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polywell) While it’s not a sure thing at this point, the indications are good that these devices will be able to provide a virtually unlimited supply of clean, safe, carbon-free energy within the next 15 years.

So cheer up! We have the material abilty to provide ourselves a standard of living undreamed of. Now, if only the economists could understand the monetary system, we might actually get to do it…

Fusion: the energy source of the future – and always will be. Colour me unconvinced. Driverless transport shows more potential in the long run, but given the absolutely massive transition costs and the likely safety (read: reliability) issues, I think it is only a long run prospect.

There’s always some potential innovations that just might work out and utterly revolutionise our lives, but I reckon an older population means that, cet par, the flow of such potential game-changers will slow. Therefore the odds that our lives will be revolutionised will also drop.

Bill’s right that the world as a whole should spend much more on basic research, but there’s an obvious free-loader problem here. With basic research no individual country can capture all the benefits so they won’t incur the costs. A small country like Australia, in particular, can only get a small part of the worldwide benefits, so spending serious money on basic research would be pretty much just altruism for us.

True, fusion is a long shot – but I believe that the Polywell approach has tremendous promise. If nothing else, look at how the Navy is funding the program: it much more of an “applied research” model, with funding contingent on specific milestones, rather than the “Here’s a few billion; get back to us if you need more” that Tokamaks have had. We should know, one way or another, in the next 15-24 months.

As for driverless cars, I really don’t see the transition as being that costly; rather than the previously proposed (and vastly expensive and unworkable) “smart highway” solutions, the evolving picture looks more like independent autos that don’t require any external infrastructure (other than GPS). It’ll be like antilock brakes – you’ll see it first on Lexuses and Mercedes, and eventually it will be standard equipment. once you’ve reached a critical mass you can do stuff like reserving lanes for them so they can “convoy”, etc. but that should be that costly. The real barrier will be legal: Such cars will have to be 100 times safer than human drivers to be acceptable to the masses, and a single well-publicized malfunction that kills someone will be enough to set it back years.

As for basic research, well, that’s what the U.S. DOD is for (come on, you didn’t think it had anything to do with “defense”, did you?) Unfortunately, weapons seem to be the only thing that the U.S. congress has no problem spending money on; fortunately, the sorts of things the military likes to spend money on (GPS, computer networks, nuclear power, “battlefield medicine”) tend to find uses beyond the battlefield…

Bill,

This is an interesting article, as it touches on social and political questions as well as economic ones. Not being a full-blooded economist, I’ll only attempt to comment on the other aspects of your text. I have two concerns / questions.

First, your assumption that:

‘…If we adequately fund our public universities to conduct more research which will reduce the real resource costs of health care in the future (via discovery) and further improve labour productivity then the real burden on the economy will not be anything like the scenarios being outlined in the “doomsday” reports…’

If you are talking about the productivity in the services sector, I would like to know how you imagine this will look like? The productivity of a person taking care of a child, an elderly person, a patient, etc. can, in my opinion, only be ‘enhanced’ by lowering wages. Which, in the neo liberal world, means importing cheap labour to perform these tasks. This creates an increasing spread of productivity and wages between low-tech jobs that can’t be enhanced and those that grow in productivity with advancing technology and know-how – more of a social than an economic problem.

The other assumption is that technological breakthroughs will reduce the cost of medical treatments. To quote my uncle, who is a doctor at a large hospital here in Switzerland: the costs of medical treatment doesn’t follow ‘normal’ economic logic. In a world where the ‘new and improved’ technique or drug automatically replaces the older one, market forces which would otherwise be expected to balance the pros and cons in an economic sense do not function properly. It is (generally rightly, in my opinion) taboo to expect anybody to undergo the inferior treatment for efficiency reasons. Also, often new treatments do not replace old ones, they just add on to the canon of available treatments. Hence, again in my opinion and notwithstanding productivity increases in overheads and the pharmaceutical industry, the spiralling health costs throughout the developed world.

The other point that bothers me is this:

‘…The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them…’

Household work that inevitably accrues, e.g. cleaning, child care, care for the elderly and ill, etc., can either be dealt with privately or outsourced to others in the private or public sector.

The classical, post-war ideal is that of the bread-winner husband and the housewife who takes care of household and social chores. This model fits in well with your statement, as it implies that those who seek work do so in highly productive areas whereas the ‘inefficient’ work takes place off the balance sheets, as it were, and doesn’t require ‘creating’ a ‘low income’ labour class. ‘Low end’ and ‘high end’ work take place within the same household, separated only by gender. But, apart from the fact that you now have most feminists stacked against you, the possibility for women crossing into more productive lines of work is left out, thus diminishing possible output.

This leads to the second model, where both partners pursue highly productive work and outsource care work to private or government entities. This model becomes more attractive, the greater the real net income difference between ‘high end’ and ‘low end’ work is. Although this is the overall most productive model, as it encourages each to seek work according to his or her abilities, it also encourages larger wage spreads within society, It also leaves open the question of who does and pays for the care work of those on the bottom end?

The third model, and the one you implicitly discourage (that’s my interpretation), is that of dividing labour into parts of both of the above mentioned. That means encouraging people to take part in different types of work by offering part-time jobs in ‘high end’ sectors and on managerial levels, while looking for ways to formalise and officially compensate the hitherto ‘informal’ sector of most household and care work. Apart from being more gender neutral than the first model, it is also more flexible in that it creates the opportunity for both partners to pursue productive work according to the stage of life they’re in and currently available jobs.

I’m not saying these models are mutually exclusive, nor that it is my business to impose my favoured one on others, but your statement did point in a direction I’m not sure you intended. I would question your view on the homogeneity of the work force and with it the assumption that increases in aggregate productivity are automatically socially beneficial.

Regards, Oliver

Oliver,

you are definitely right that there are limits to how much productivity in the service sector can be increased. Over thousands of years of this civilization the costs of raising a child have gone up big time, i.e. efforts and resources spent on each child increased many-fold. However, we live today where we live and the progress has never been this fast. Yes, you can not increase productivity of services, but this is not how you create growth. A barber 100 years ago spent the same amount of time per client as he does today. But today we have internet, live two times longer and produce, say, 5 times more goods and services during our productive lives. So the costs of raising a child, while definitely have increased in absolute amount, might actually be much lower on this latter metric. And along these lines, health care costs might and will increase in the future, but relative to all benefits they might not look like a dead-end. I am sure you will agree that cancer has tremendous costs and once that break-through is made, the benefits will be enormous. And my favorite one – dentists (not that I am a doctor, I am just scared of them). One day it will be possible to take a pill and one month later you will have a new tooth. No magic here – just turning on processes that are already programmed in our bodies when we lose baby teeth. Does it sound like a enormous benefit? 🙂 So I am not scared and completely agree with Bill that we need to invest into education and research.