I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

When leading economists become part of the problem

In yesterday’s (August 23 2009) Financial Times, so-called financial markets expert Nouriel Roubini wrote that The risk of a double-dip recession is rising. The American academic was recently in Australia as a speaker at the Diggers & Dealers Forum which is an annual mining conference. The problem is that Roubini is an influential advisor to the US Government and so will have a hand in determining the direction of fiscal policy. He continually demonstrates, however, that he does not understand how the fiat monetary system operates and in that context becomes part of the problem.

Roubini has achieved (self-promoted) celebrity in recent years as allegedly “one of the few economists who predicted the crisis”. Many readers have asked me about his theories etc. The debt deflation lot are always trying to claim credit for predicting the crisis – true enough they did in a sort of way. But modern monetary theorists predicted it years ago as the neo-liberal agenda turned into budget surpluses. You cannot understand the debt build-up independently of the conduct of fiscal policy. Anyway, I digress.

In his Australian (at Kalgoorlie) address Roubini said:

The recovery of Australia is going to be more robust than other advanced economies … [however] … in the short-term the biggest threat to the global economy is deflationary forces …

Among other reasons noted was that we have less public debt which is to our favour. This is a common claim by mainstream economists – that if you started this recession with budget surpluses and low public debt levels then the national government had more “stimulus room” than if otherwise. The claim is totally false and just reflects the wrong-headed macroeconomic theory that these characters use to beguile the general population.

First, a budget surplus yesterday gives the government no extra capacity today to net spend. Not a single solitary dollar! Indeed, for a nation that had been running surpluses the inherited fiscal drag will make things worse once private spending falters. The only way an economy like Australia (which does not have huge net export revenue) can grow when the government sector is in continual surpluses, is if the domestic private sector is accumulating ever-increasing levels of debt.

Debt-deflationists do not tie that connection together (which is derived from a basic understanding of national accounting) and so misunderstand the way money is created and the way economies grow and stall.

Second, the level of public debt that a government holds makes zero difference to its capacity to engage in fiscal stimulus. Zip! We could have had enormous levels of public debt and still invoked the same fiscal stimulus. All low levels of public debt means is that the non-government sector has less of its wealth in risk-free assets and less of its investment income in risk-free annuities provided by the government.

Roubini also claimed in his Kalgoolie speech that the AUD would rise as commodity prices rose again but that this would trigger higher interest rates because the RBA will want to curb inflation. What? A higher AUD is deflationary in the sense that it reduces import prices. Further, the demand add coming from a recovery in mining will not be sufficient to raise capacity utilisation rates in the general economy to a point where we run out of real capacity.

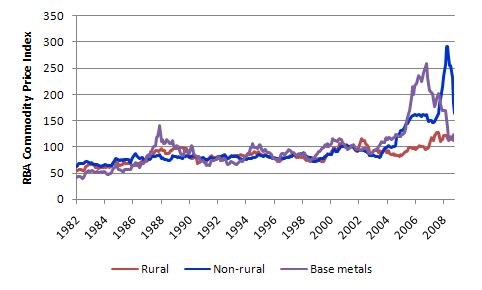

The following graph shows the evolution of the RBA Commodity Price Index for rural, non-rural and base-metals. The recent mining boom is there for all to see as is the collapse in commodity prices at the onset of the global recession. The evidence suggests that while export volumes might rebound somewhat the contract prices will not.

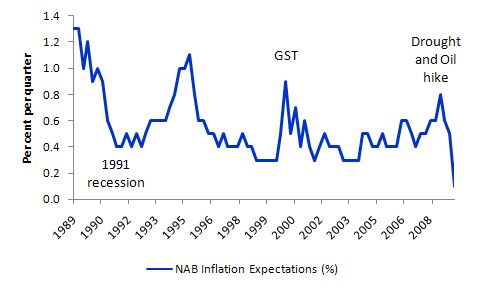

What about general inflationary expectations? The following graph shows the NAB inflationary expectations series for Australia from June 1989 to March 2009. The series had been running at a consistent 5 per cent or more through the 1980s (with wiggles) and it was the 1991 recession that expunged inflation and inflationary expectations from the landscape. The spikes since are all once-off type factors although if the demand for oil rises again that might trigger a renewed cost-shock on that front. But it will be nothing intrinsic to budget deficits unless you want to claim that the deficits drive growth which drives resource shocks. Okay, but that is a general problem and not confined to deficit-stimulus.

At present, inflationary expectations are at their lowest values since this series was made available and I fail to see that situation changing. I agree with the debt-deflationists that the main danger is deflation in which case what is Roubini thinking about?

So Roubini’s statement is just blab – the sort that professional economists make all the time because they get their logic from the (gold-standard) mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and no-one in the general public can stand them up for speaking nonsense.

In the FT article I noted at the outset, Roubini continues this theme but then professes to make statements which impact on our understanding of how the fiat monetary system works.

First, I agree with him that “the global economy is starting to bottom out from the worst recession and financial crisis since the Great Depression”, although don’t tell the labour markets that!

I also agree with him that “late last year, policymakers who had been behind the curve finally started to use most of the weapons in their arsenal” and that “effort worked and the free-fall of economic activity eased.”

Roubini then goes onto discuss the alphabet along the lines of my blog yesterday – More fiscal stimulus – what shape recovery?.

He splits the world up into those countries that will remain in recession for the rest of this year at least and those (like Australia) where “recovery has already started”.

By way of nitpicking … Australia’s latest national accounts (June quarter) are not out yet and they expect to show negative growth. And it is also clear the labour market is not in recovery. But we know what he means – he is looking at the leading indicators.

He disputes the V-shape view and instead opts for the U-shape recovery and provides several reasons to justify that conclusion. But recall my blog yesterday where I made the distinction between what happens to GDP growth and what happens to employment growth. The former might be V or U but the latter is typically a sharp decline followed by a slow, painful and drawn-out recovery where unemployment continue to rise for years after the GDP trough is passed.

Anyway, so far so good. It is always good to agree with something. But then things deteriorate.

He says that because of lagging labour markets demand recovery will be slow as will the growth of labour productivity. Labour productivity will likely bounce back to its (rather pitiful) trend fairly soon because of the hoarding that is going on at present. But rising unemployment is always a bad omen for aggregate demand and it is spending which drives the show.

But this just means that the budget deficits probably have to rise to maintain spending growth. Roubini doesn’t consider that a viable (sustainable) option – a point I will come back too.

He also considers the banking system to be a constraint on growth now. He says:

… this is a crisis of solvency, not just liquidity, but true deleveraging has not begun yet because the losses of financial institutions have been socialised and put on government balance sheets. This limits the ability of banks to lend, households to spend and companies to invest.

I agree that the true exposure to the debt bubble is undisclosed although you can make some pretty reasonable calculations of the CDOs that are still out there. But unlike the debt-deflationist perspective the fact that increasing volumes of this stuff are now on government balance sheets is a plus.

Further, limits to lending are constrained by the volume of credit worthy customers. Loans create deposits and the capacity of the banks to lend has nothing to do with the take-over or whatever by governments.

Finally, and this point should be continually made. A bad debt today was a good debt yesterday and the only difference is that the holder of the debt is now unable to service it. Typically this is because of unemployment.

There is no doubt that dishonest practices in the US (and elsewhere) inflated land values and/or the incomes of borrowers in order to generate sales commissions in the knowledge that the debts would be bundled up (securitised) and on-sold to some other party. There is no doubt that this made risk assessment virtually impossible.

But this might only be a small fraction of the outstanding debt. A significant volume of the debt would have remained “good” (non-toxic) if the governments had have been supporting their economies earlier with enough deficit spending.

Roubini then says:

… in countries running current account deficits, consumers need to cut spending and save much more, yet debt-burdened consumers face a wealth shock from falling home prices and stock markets and shrinking incomes and employment.

Sounds like a paragraph from any mainstream macroeconomics textbook – all of which misunderstand the nature of a current account.

Notwithstanding what I said above about good and bad debts, I agree that it is is an unsound growth strategy to rely on consumer spending which is driven by increasing private debt levels while the government sector is running (or attempting to run) surpluses. This strategy cannot sustain itself.

But that is a separate issue from the current account. Consumers can maintain spending and save as long as the saving is supported (financed) by government deficits. Then the only risk is inflation.

Further, the reason consumers can enjoy imports in excess of what their nations export is because foreign savers want to accumulate financial assets denominated in the currency of that country. So imports finance the saving preferences of the foreign sector rather than the other way around. Mainstream is economics is always backwards.

Roubini offers more:

… the financial system – despite the policy support – is still severely damaged. Most of the shadow banking system has disappeared, and traditional banks are saddled with trillions of dollars in expected losses on loans and securities while still being seriously undercapitalised.

Yes but this is separable from the real sector as long as the government deficit is large enough. There has to be some serious restructuring in the financial and banking sector across the world. The worst thing about the current stimulus packages have been the way significant dollops of public money have gone to further the private interests of the top-end-of-town. In varying degrees this has happened in most countries.

My view is that if a bank cannot pay up it should be nationalised and the monetary capacity of the government then be used to guarantee deposits.

The we read from Roubini that:

… the releveraging of the public sector through its build-up of large fiscal deficits risks crowding out a recovery in private sector spending. The effects of the policy stimulus, moreover, will fizzle out by early next year, requiring greater private demand to support continued growth.

One has to always stay calm when reading that sort of nonsense. Again this is just a rehearsal of a paragraph from any mainstream macroeconomics textbook and is without content when applied to a modern monetary economy.

What he is reciting from the textbooks is that the (voluntary – that is not in the textbook!) bond issuance associated with the rising net public spending will drive up interest rates because they use up scarce investment funds. In turn, this stifles (crowds out) private spending.

Even if it was true, the solution would be to keep increasing deficits in lock-step with the decline in private spending (public sector = 100 per cent of GDP! – sorry I am calm).

The reality is that deficits drive interest rates down (notwithstanding that bond yields out there on the yield curve might be volatile for various reasons). The central bank sets the interest rate and can significantly influence the structure of longer-maturity rates. In absence of the central bank using public debt sales to influence the interest rate target, the deficits would drive the short-term interest rate down to zero and ensure, concomitantly, that the longer rates were also low.

Further, if the impacts of the policy stimulus “fizzle out” and there is no corresponding pick up in private spending then there is clearly one option – more fiscal stimulus. Growth can be maintained indefinitely this way if the politics allowed it to.

Things get even uglier as we read on.

Roubini says that on the one hand:

… there are risks associated with exit strategies from the massive monetary and fiscal easing: policymakers are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. If they take large fiscal deficits seriously and raise taxes, cut spending and mop up excess liquidity soon, they would undermine recovery and tip the economy back into stag-deflation (recession and deflation).

Anyone who had a deep understanding of how the fiat monetary system operates would not say this. Conclusion: there is no understanding displayed.

If the governments start reducing their deficits too soon there will be a massive deflationary bias introduced into the system and a W-shaped outcome would almost be certain. True. We agree on that.

The deficits will unwind by themselves as the private sector spending resumes and the automatic stabilisers generate increased tax revenue and reduced welfare spending outlays. The discretionary component of the deficit then would be assessed in terms of the size of the spending gap that has to be filled. While the timing might be tricky it is not rocket science.

Any government that started putting up taxes or cut spending to “mop up excess liquidity” would be vandals and deserve the sanction of their electorates. They would also reveal they know as much about the operations of the monetary system as Roubini.

Further, what does “excess liquidity” mean anyway? This is from the Quantity Theory of Money chapter of the textbook and is taken to mean – “too much money chasing to few goods”. But that is basically a vacuous concept. Is he worried about the reserves in the bank system? Does he think they will suddenly lend them all out because they need deposits to lend and then this would be inflationary? With more than 10 per cent of the willing labour unemployed (in the US) how are their too few goods?

The way to think about it is to assess how much demand there is in the system relative to the real capacity of the economy to respond to it. Simple as that. The level of bank reserves have little to do with that assessment. And as regular readers will appreciate – banks do not need deposits to lend. It is the other way around – loans create deposits and reserves are added afterwards.

But on the other hand, Roubini says:

But if they maintain large budget deficits, bond market vigilantes will punish policymakers. Then, inflationary expectations will increase, long-term government bond yields would rise and borrowing rates will go up sharply, leading to stagflation.

He must have turned over the page of the mainstream macroeconomics textbook. That takes us to the section on the amorphous global bond traders who hate deficits and push interest rates up which then combines with rising inflationary expectations so that recession (arising from the crippling interest rates) is accompanied by inflation.

My first reaction was – yes Japan! Years of high deficits, huge Yen-denominated (voluntary) public debt issuance, zero interest rates and deflation. Right on, those vigilantes must have been out having a round of golf for 15 years or so!

The only risk of large deficits is inflation and that will occur if nominal spending growth outstrips the real capacity of the economy to respond to it by producing real goods and services. We are so far from that situation with unemployment rising and deflating spending growth.

Once the economy picks up, and deficits fall automatically, the government will get the message soon enough whether discretionary spending needs to be trimmed or less spending capacity left in the private sector (that is, they might put tax rates up to drain private purchasing power).

My friend and some-time co-author Warren Mosler reacted to the FT article in correspondence with me today in this way:

Just in case you thought he … [Roubini] … knew how the monetary system works – the nonsense about the penalty for deficit spending being anything but possible inflation makes him part of the problem … Mainstream economics is a disgrace.

I couldn’t have said it better.

As a final point, I was reminded by a reader that I didn’t respond to a statement that debt-deflationist Steve Keen was alleged to have made about modern monetary theorists (such as me). The statement purported to have been made was:

In a nutshell, they have a “Chartalist” view of how money is created which sees it as a government invention, even though they also support the general Post Keynesian position that the money supply is endogenously determined. I don’t see how they can reconcile the two positions, and they have yet to develop any model of money creation (of which I’m aware anyway) that puts any substance to the Chartalist view that differs in any significant way from the “money multiplier” argument that I (and the data!) reject.

I didn’t respond because it is almost beyond belief that anyone who has read our work would say this.

Vertical transactions by government create/destroy net financial assets in the non-government sector. Only government can do this. Transactions in the non-government sector all net to zero. Horizontal transactions between non-government entities then leverage off the net financial assets created by the government. Private banks create financial assets by lending – loans create deposits – but at the same time create an offsetting liablity.

This is so far removed from the money multiplier concept – you can read what I have written about that on this blog by reviewing the following posts.

In my latest book with Joan Muysken, I also spell the technicalities of all this out in detail.

I guess the actual issue that I should have responded to relates to the statement “of which I’m aware anyway”. You can consider what I might think about that yourselves.

Digression: yet another supply-side training program does well Not!

I received some data today (more some other time about it) that showed that under the Federal Government’s Productivity Places Program, 95,000 referrals had been made to training providers. The data suggests that only 5,000 of these persons gained employment (and I don’t know what sort of job or whether they are still employed).

Training divorced from a paid-work environment is a waste of resources. When will they ever learn?

Bill,

Well said on the money multiplier and chartalism reply. He’s not the only one that’s made that argument, but it’s always simply incomprehensible to me that someone could make such an interpretation of our position. Seems to me they don’t grasp the difference between bank lending requiring prior reserves and bank lending creating a short position in reserves. They appear to get confused by our use of the term “leveraging,” believing it means prior reserves must exist before a loan can be created . . . some first semester accounting would go a long way here yet again.

I’m always willing to accept that chartalism may have some flaws if someone can ever point them out, but I still haven’t seen anyone critique chartalism who has also demonstrated a clear understanding of chartalism to begin. As yet another example, I was asked a few years ago to evaluate a submitted article purporting to critique chartalism; unfortunately, it was critquing some strange monetary theory that the author believed was chartalism. I explained as much in detail in my evaluation, but the article nonetheless was ultimately published with essentially no changes.

Best,

Scott

Question:

If, as, and when inflation risk does appear in the future, does the size of the deficit/debt at that time have anything to do with the level of that risk at that time?

Dear anon

If the inflation risk is emerging because nominal spending is approaching the real capacity of the economy to absorb it and respond to it by producing more real goods and services then anything that is adding to demand will have something to do with the inflation risk.

The size of the deficit indicates a level of net spending that is being added to aggregate demand. Similarly high stocks of public debt will at any given interest rate mean higher servicing payments which also add to aggregate demand. But that is equivalent to saying that high levels of consumption and investment and net exports have something to do with inflation risk as the economy approaches the real capacity limits.

There is nothing special about the government contribution in that respect. How the “risk” is reduced becomes a political choice – more public less private spending (raise taxes) or vice versa (reduce net public spending).

Further, the analysis of a cost shock inflation is somewhat different and the relation of budget deficits/debt to that sort of dynamic is largely irrelevant. You can hardly blame the fiscal policy of a sovereign government when OPEC doubles the oil price. That is not to say that a fiscal adjustment may be required in that instance. But it all depends on the circumstances.

best wishes

bill

Dear Scott

I was giving a talk at a conference/workshop (major national affair) recently and one question I received was “this is just your opinion” (in relation to my statement that to understand macroeconomics you have to start with the national accounting statement that a government deficit(surplus) is exactly (unequivocally) equal to a non-government surplus(deficit) – $-for-$. I was told that this might not be the case and why should anyone trust my opinion over those who thought otherwise. It almost beggars belief that commentators dispute something as intrinsic as that without first really understanding it. They then proceeded to argue that deficits were inflationary which more or less proved the “accounting statement” was a matter of opinion.

I find that a lot. In reaction to presentations I make, there seems to be an energy in question time (abusive or polite) that manifests as a stream of consciousness incorporating a confused cocktail of (neo-liberal) ideas which all spurt out in a row and get to the inflation, higher taxes, intergenerational burden in about 20 seconds – conflating accounting facts which other matters that are debatable and packaging them into the same conclusion – “your policy advice would be dangerous and bankrupt the country”. Never do these critiques remotely capture the argument from first principles and then agree that issues such as “the point we get to the inflation constraint” is the interesting one. The fact that government deficits add to private savings is an accounting statement and for me rather uninteresting. The real debate should be about full employment, inflation, income distribution, public versus private goods, education and skill building, productivity etc.

In terms of your refereeing experience – sometimes I wonder why journals bother to get waste my time seeking an opinion when they just publish what they want anyway no matter how mistaken the analysis is. Happens all the time – bi-weekly almost. I am thinking of giving up refereeing.

best wishes

bill

Bill, can you please reoplace my lat post with this one – I hit submit too early.

Dear Bill,

Do you think Malthusian population doctrine and the ne0-liberal epidemic of surplus mania are one in the same thing?

Malthusianism required the wages fund to express how an increasing population would press against the means of subsistence. With the surplus mania myth being spun in recent times the wages fund has been replaced by the governments budget constraint which if exceeded will supposedly have dire consequences for the populations ability to maintain it’s standard of living (subsistence).

Once the evidence mounted (productivity / technological growth) to the point where Malthusianism was no longer in favour the mainstream dropped it, and its no longer useful collary the wages fund doctrine like a hot spud.

I just hope that with more evidence like you have recently presented (this article and the graphs of Japan) people will drop neo-liberalism like a bad habit and as a consequence the notion that the governments budget position has any economic validity in a modern money economy.

Cheers, Alan

The hysteria continues after the US CBO announced its projections.

New York Post has an “Astonomics” which says “If you stacked up 9 trillion one dollar bills, the pile would be high enough to reach the moon (238,000 miles) and return – plus go half way back”

Good! Lets take the trip.

On a more serious note, a waste of time. However on an optimistic note, the 2019 percentage debt held seems to be around 68% – thankfully they didnt project it to go from around 55% of GDP to 40% or whatever.

Very interesting site – though just a quick question, I may have misunderstood but you essentially say that public debt of any level is not a concern, and whilst I totally appreciate and agree with the basis of what your saying, is it really unlimited, especially as far as Australia’s debt is concerned? But surely it will eventually have SOME impact on something. I ask because the US is a nation that just keeps getting more and more debt. Is a 2,3,5,10,20 Trillion of debt not an issue? Thanks again.

Actually – I think this blog answered my question, https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=4603.

Shaun,

Welcome to the site.

No public debt is an issue! The government in a country operating with floating exchange rates faces no constraint. Government debt = Private Sector Net Saving by identity. Because of this, the government cannot keep spending, however. Questions like which is better – $1T or $9T – depends on the private sector’s spending and savings desires. Imagine, if the government starts spending too much, the private sector will get lot of money in their pockets and their spending will grow as well. This is good for producers and their inventories will move fast and seeing this opportunity, they will increase prices instead of producing more. So in a sense, the government cannot solve all problems of the economy so fast. However, this is really a big tool (BIG) and has been ignored by majority of economists and policy makers simply because of their refusal to understand anything.

This is a very short answer to your question – even if you believe this, many more questions will pop up in your mind. May I suggest you visit the blog index Complete billy blog on one page! and check out the category Debriefing 101?

Hi Ramanan, Thanks very much for the explanation and link – I will definitely read through it all – shaun,

Shaun,

Unemployment is a far worse problem than a few trillion dollars of debt for a government who through its central bank is the monoplist supplier / issuer of fiat.

Until everyone who wants a job has a job with enough hours to provide them an adequate living standard then any government who refuses to run a deficit is effectively declaring war on its own citizens.

Cheers, Alan