Yesterday (April 24, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest - Consumer…

Forget the record deficits and public debt – focus on what the net spending is doing to advance well-being

Yesterday (October 21, 2020), the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) released the latest – Public sector finances, UK: September 2020 – which, predictably tells us that government borrowing was “£28.4 billion more than in September 2019 and the third-highest borrowing in any month since records began in 1993” and that the public debt ratio has risen to “103.5% of … GDP … this was the highest debt to GDP ratio since … 1960.” Shock horror. While I yawn. The financial media went to town on the data. The Financial Times article (October 22, 2020) – UK government borrowing reaches record in first half of fiscal year – claimed the second wave that is now sweeping the northern hemisphere “have dampened hopes” that the stimulus “could be quickly scaled back” which has “fuelled concerns over the US’s mounting public debt”. It didn’t clarify as to who was concerned or why. The old canards seem to die slowly. Meanwhile, the IMF has changed tack somewhat after its tawdry display during the GFC. Overall, we should be relaxed about the records being set (deficits, public debt) and focus on what the net spending is doing to advance our interests. Focusing on the financial parameters will just divert our attention away from what is important.

British fiscal data topping the charts!

The only concern that the FT article mentioned was quoting a management consultant who said the ONS data release:

… may add more tension between the need to respond to renewed Covid outbreaks and preserving the public purse.

Exactly what might “preserving the public purse” mean?

The English meaning of the word – ‘purse’ – is:

… a small pouch of leather or plastic used for carrying money, typically by a woman.

Gender issues beside, a person needs a ‘purse’ to store currency so they can go shopping, which in modern times are more receptacles for credit cards.

So a purse traditionally implies a prior stock of currency.

The currency-issuing government neither has nor does not have currency as a ‘state’ variable. It just spends its currency into existence … boom, there it is – a number in a bank account.

But this idea that there is some trade-off between the health responses and the fiscal capacity of the government is erroneous reasoning and the type of (il)logic that has created such poor outcomes over the last several decades.

When the government spends its currency into existence a flow of spending enters the non-government sector, which stimulate sales, production, income generation, and employment.

Those flows have no ‘state’ – they are not a stock that carries over to another period.

So there is never a question about the capacity of the British government to render those flows as large as they like.

How large should they be?

Context!

Consider two scenarios.

At full employment, inflationary pressures will arise if government competes at market prices with non-government spending for productive resources.

To increase its use of productive resources, but avoid inflationary pressures, the government has to ‘free up’ resources.

Taxation is one option because it reduces non-government purchasing power and creates the real resource space to accommodate non-inflationary government spending.

Importantly, the taxes do not provide any extra spending capacity for government.

In the second scenario, idle productive resources can be brought back into productive use with higher deficits. There are no constraints – financial or resource – on such government spending.

Ask yourself where Britain is at present.

The answer is that it is very firmly in the second situation, which means it can just type flows of spending into bank accounts – nothing necessary to ‘preserve’ other than jobs, private incomes, services, health care, and all the things that matter.

Fiscal space is much broader than mainstream economists suggest and can only be defined in terms of available real resources rather than numbers in fiscal statements.

The ONS public finance data tells us nothing about fiscal space.

But there data on unemployment, underemployment, GDP is where we have to go to see how much (non-inflationary) fiscal space there is.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) focuses on how policy advances desired functional outcomes, rather than what the state of the deficit might be.

To maximise efficiency and minimise output losses, the responsibility of government is to spend up to full employment.

The fiscal outcome will be whatever is required to achieve that functional goal and will be largely determined by non-government saving decisions (via automatic stabilisers).

Under current institutional arrangement, where the government matches its net spending flow in a period by issuing new debt, the stock of debt obviously rises, which is what the ONS is reporting.

When government bonds are issued to match deficits, the central bank effectively just marks down reserve accounts and marks up a ‘treasury debt’ account.

The bond sales do not alter the net financial worth in the non-government sector in the first instance.

The debt issuance is a redundant part of the process and a hangover from past currency arrangements (pre 1971).

Governments could avoid all the nonsensical commentary about ‘record’ debt levels and the rest of it by abandonding the debt auctions.

Redundant means it is not required to accomplish the goals of the spending.

The current system of debt-issuance in Britain – the gilt auctions – was introduced in 1987 as part of the so-called – Big Bang – which was the “the sudden deregulation of financial markets” that the Thatcher government introduced in 1986.

In July 1995, the Treasury released the – Report of the Debt Management Review – which described the elaborate machinery that had been put in place to facilitate this redundant practices.

Lots of high-paying jobs, consultancies, kick-backs and the rest of it. But little functional purpose other than to maintain the system of corporate welfare that the investment banks had become used to.

It also concluded that “Auctions will constitute the primary means of conventional gilt issuance”, which means that the government allows the private bond speculators to set the yields.

It recognises that, even within a debt-issuance mindset, the alternative (and prior) system of tap sales can “function primarily as a market management mechanism.”

In this blog post – Direct central bank purchases of government debt (October 2, 2014) – I discussed the way the Australian government shifted in the 1980s from a tap system of debt sales to the current auction system.

In the former system, the government set the rate it would pay on debt issued and if the bond markets were not happy with the return and declined to buy the debt, the central bank would always buy the difference.

In the neoliberal era, this was the anathema so they shifted to a system where the government would announce an amount it wanted to borrow and the bond dealers would then bid for the debt by disclosing yields they were prepared to pay.

The auction model merely supplies the required volume of government paper at whatever price is bid in the market.

So there is never any shortfall of bids because obviously the auction would drive the price (returns) up so that the desired holdings of bonds by the private sector increased accordingly.

And if there are ‘concerns’ about the debt in the financial markets it is not showing up in the auction data.

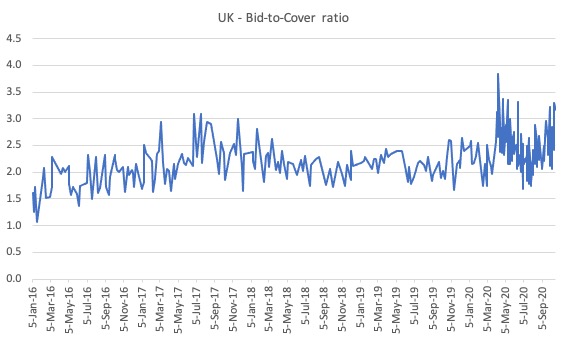

The following graph shows the latest gilt market auction bid-to-cover ratios which are well above 2 mostly – which means there are twice as many sterling bids than the gilts on issue.

Please see this blog post – Bid-to-cover ratios and MMT (March 27, 2019) – for more information on that.

Enter the IMF to tell us why all this debt worry is misplaced

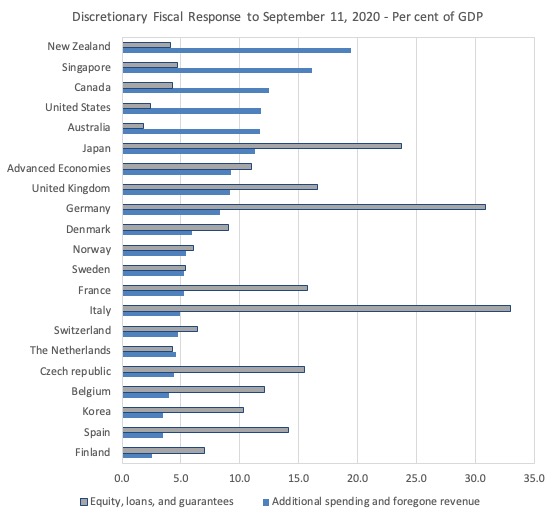

The IMF – Fiscal Monitor: Policies for the Recover – issued October 2020, provided data for this graph.

It shows the discretionary fiscal response since the pandemic began and up to September 11, 2020.

The two components of the discretionary fiscal responses have been:

(a) Additional spending and foregone revenue (temporary tax cuts).

(b) Liquidity support – loans, guarantees and equity injections by government.

There has been huge variation across the nations shown in terms of the bias towards (a) or (b).

In general, additional spending is much more expansionary than items under (b).

The IMF make an interesting point:

Advanced economies and large emerging markets account for the bulk of the global fiscal response … their central banks were able to provide massive monetary stimulus and purchase government or corporate securities while retaining credibility to deliver low inflation … their treasuries were able to finance larger deficits at low interest rates.

Of course, any central bank can purchase its own government’s debt – left pocket/right pocket stuff.

And any central bank can keep yields low on that debt if they desire, which means the ‘low interest rate’ story really is misleading.

But the important part of what is going on right now is that:

1. “The fiscal response, coupled with the sharp decline in output and government revenue, will push public debt to levels close to 100 percent of GDP in 2020 globally, the highest ever.”

2. And, yes central banks are buying most of the debt:

Central banks in several advanced economies and emerging market and middle-income economies have facilitated the fiscal response by directly or indirectly financing large portions of their country’s debt buildup.

So nothing to see here.

Record debt issuance, central banks buying the new debt, government buying and owning its own debt, end of story.

But, while there is nothing to see here in terms of the ‘economics’, this is a huge shift in mindset.

The IMF admit that the:

… massive fiscal support undertaken since the start of the COVID-19 crisis has saved lives and livelihoods.

So fiscal policy is not ineffective as many mainstream economists have led us to believe over the last several decades.

Now it is saving lives and livelihoods.

Paradigm shift underway.

Not quite.

The IMF cannot quite let go:

Record-high public debt levels limit the room for further fiscal support …

No. Especially when the central banks are buying up the debt and can buy all of it if the government wanted. Japan anyone!

Meanwhile, in the Eurozone, the game must be nearly over.

The IMF projections suggest that by 2025, the debt ratios in the Euro area will be 80.9 per cent of GDP, with France at 114.6 per cent, Italy at 141.5 per cent, Spain at 106.4 per cent.

Both France and Spain among the big 4 will violate Stability and Growth Pact deficit limits and I suspect Italy will too (given the ridiculous IMF forecasts to the contrary).

They will not be able to return to their fiscal rules within any foreseeable time horizon.

So how will that play out?

The point is that during the GFC, the IMF was out there forcing governments to cut net spending and accelerate the pace of consolidation which really meant they were just consolidating the elevated levels of unemployment and poverty.

Now, 10 years later, there is some give in their position and we are not reading anything about “growth friendly austerity”.

In their recent – World Economic Outlook, October 2020: A Long and Difficult Ascent – (released October 2020), the IMF project that world output will languish and fiscal deficits will have to remain at elevated levels for the foreseeable future.

I have just finished an academic paper that will be published soon (details available later) where I argued that Capitalism is now on life support with fiscal policy dominant.

Significantly larger and sustained fiscal deficits will be required indefinitely and that we should be comfortable with that.

Focusing on the size of the deficits is to focus on the wrong problem. The way out of the crisis requires an orthogonal shift in policy thinking and new theoretical understandings.

The usual narratives about the dangers of deficits and public debt are giving way to a new understanding.

This policy shift is diametric to what mainstream macroeconomists have been advocating for decades and their analytical framework cannot provide an understanding of the fiscal space available to governments nor the consequences of these policy extremes.

MMT has consistently advocated a return to fiscal dominance and disabuses us of the claims that deficits and debt are to be avoided.

MMT defines fiscal space in functional terms, in relation to the available real resources that can be brought back into productive use, rather than focusing on irrelevant questions of government insolvency.

Conclusion

MMT economists have always held the view that a focus on deficits and debt aimed at assessing solvency thresholds and the like has never been justified and has underpinned destructive policy interventions that have undermined prosperity.

Now, as never before, the scale of the socio-economic-ecological challenges before us requires a rejection of the deficit/debt scaremongering. Meeting these challenges will require significant fiscal support over an extended period.

Such fiscal support is necessary to sustain income growth to allow the non-government sector to reduce its debt levels and to provide for jobs growth. But it should also target longer-term challenges, such as restoring some self-sufficiency in manufacturing; reforming the gig economy that has exposed millions to poverty during the pandemic; supporting regions that have experienced a major loss of firms (for example, tourist destinations); address the housing crisis; and, importantly, accelerate the transition away from carbon-intensive production and consumption.

Even before the pandemic, the climate issue suggested large fiscal deficits would be required in the transition phase. The health crisis has added another dimension to that need.

The old orthodoxy does not provide a reliable framework for understanding these options and consequences.

It is likely that relying on ‘business as usual’ will result in an inadequate level of fiscal support being provided and a premature withdrawal of that support as the old debt and deficit themes return.

MMT provides a comprehensive macroeconomic framework, which allows us to understand that the problem into the future will not be excessive deficits and/or public debt.

Rather, the challenge is to generate productivity innovations derived from investment in public infrastructure, education and job creation.

And relax about the deficits and record debt.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Typo:

“The English meaning of the word – ‘word’ – is”

The mainstream struggles to keep their lies alive.

“And if there are ‘concerns’ about the debt in the financial markets it is not showing up in the auction data”

The UK Debt Management Office (DMO) has been desperately trying to “reassure the market” that it is still a price taker, not a price maker. See https://www.omfif.org/2020/08/uk-dmo-chief-on-crisis-borrowing/

Yet if you look at the 3 Month Treasury Bill data from the weekly tenders you’ll notice that the price started to creep up around the end of March and into the beginning of April as the pandemic started to impact on government cash flow.

At which point (April 9) the DMO reminded the market about the Ways and Means Account (HM Treasury’s permanent overdraft at the Bank of England), and that all the repo’ing and TBill issuing it does is just an alternative to using the Ways and Means at the Bank Rate. At which point the rates dropped again.

There was never any need to use the Ways and Means account given the level of excess reserves in the system. It was essentially a reminder that the DMO is not so bound by its KPIs that it could be gouged on price, and that “the market” could either have the extra interest, or it could have none.

This week’s DMO Annual review has the complete story in Objective 1.1

DMO Annual Review 2019-2020, pp 35 https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/17019/gar1920.pdf

Allegedly the DMO can get reserves from the money market at less than the Bank Rate overall using money market games

(ibid, pp37)

One of the other objectives is: “Cash management operations and arrangements should be conducted in a way that does not interfere with monetary policy operations.” (pp34)

Quite how they square those two is one of those mysteries we have yet to get to the bottom of.

I suspect the answer is: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

Would Bill consider re-writing through the MMT lens; Goal 17 (of 17 goals) in this aspirational UN document from October 2015; ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’;

Goal 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development;

Finance

17.1 Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection

17.2 Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments, including the commitment by many developed countries to achieve the target of 0.7 per cent of ODA/GNI to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries; ODA providers are encouraged to consider setting a target to provide at least 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries

17.3 Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources

17.4 Assist developing countries in attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies aimed at fostering debt financing, debt relief and debt restructuring, as appropriate, and address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress

17.5 Adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least developed countries

Here we have The Guardian (of misleading the public on economics) today:

Phillip Inman: ‘City analysts siad the fall in inflation in 2020 to below 1% was likely to continue for many years, allowing the Bank to keep interest rates ultra-low and letting the government maintain high levels of borrowing (from it’s other pocket!) through much of the decade’

Larry Elliott: ‘the financial markets are supremely relaxed about the deficit ……. A nagging concern is that the markets will have a change of heart and make it more expensive for the government to fund the deficit.’

It has always puzzled me why the Furlough scheme with its 80% payment rate was considered generous. Surely this misses the point. 80% was the rate necessary to ensure that all the industries that could still work throughout the pandemic would not experience any significant drop in demand for their produce. Such a drop in demand would have further exacerbated the unemployment problems directly created by the pandemic. The 80% Furlough rate was based on an assumption that some 20% would be unable to work throughout the pandemic. And as that 20% would spend some 80% or their earnings in the sector which could continue to work through the pandemic therefore it made sense to set the Furlough rate at 80%.

Although the Furlough scheme was a move in the right direction it had some serious limitations which resulted in those claiming universal credit increasing from 1.2 million in 2020 Q1 to 2.7 million in 2020 Q3.

Phillipp Inman and Larry Elliott of The Guardian like to pretend to themselves they have a moral compass. They clearly don’t writing all this right-wing zombie crap despite repeated efforts to explain to them how the UK reserves based monetary system actually works. They are closet Tories and need to be ignored!

There is a set of broad but connected problems in the political economy. The economy must:

1. Provide everyone one with a livable income;

2. Ensure all needful work is performed; and

3, Be efficient and sustainable.

I will address the first two items for this topic since more discussions are arising in public discourse about the UBI or LBI and the JG. I would certainly be pleased if Bill Mitchell would comment on whether my thinking is on track of off-track.

The conventional economic fear seems to be that if all adult persons have potential access to an LBI (Livable Basic Income) without work and without the need for a job-seeking test then too many will opt to not work and needful jobs will not be filled. On a first analysis, the difficulty (aside from the sheer lack of jobs) would seem to be the relative setting between an LBI and a minimum wage meaning the gap between them. There is a practical floor to the LBI. The LBI has to be high enough to be livable. There is a ceiling to the minimum wage. Set the minimum wage too high and few employers will hire new and relatively unskilled workers at that rate. The LBI floor and the minimum wage ceiling may in practice present a gap which is too narrow to tempt potential workers from the LBI group to the minimum wage group.

There is a path through this conundrum via the JG (Job Guarantee). I am not sure if my proposal here is consistent not with the JG theory developed by MMT proponents Bill Mitchell et. al. As I see it, the policy could be stepped as follows:

A. Pay an LBI which is livable and has no work-test. Remove all work tests from the welfare system.

B. Pay a JG (JG government job) minimum wage which has a sufficient differential to attract able entrants off the LBI. Set the rate empirically. Via research (what pay would attract you to a JG job?), and a phased introduction, commence the JG wage at a level to attract a small initial influx. Gear up the system by increasing the JG minimum wage gap over the LBI over time. Only accept JG applicants from the LBI pool and these applicants will be voluntary (but “advertised at” and encouraged). Ensure the JG provides full training and that it skills people up. It will eventually serve as the nation’s training and apprenticeship program. If the JG minimum has to rise above what private employment would pay for an unskilled worker this will not be a problem. Private employment can then operate significantly in the zone of bidding for now skilled workers from the JG system and paying higher than minimum wages for them, to attract them across from the JG.

This system should be operated empirically. That is to say, the rate of LBI is set with respect to cost of living measurements, the rate of JG is set with respect to the government macroeconomic targets for attracting workers to the JG, and finally the levels of skills training in the jobs of the JG are set with respect to government macroeconomic targets for making JG trained workers attractive enough to private enterprises to warrant an attracting above-minimum wage offer.

Along with this framework, natural monopolies would be nationalized and strategic industries nationalized if private enterprises elected to not perform them due to seeing inadequate profit in them. Under this overall framework, private enterprise would be encouraged to compete not only against each other but against some government enterprises and thus to prove their boasts that they are more efficient than government enterprise in certain competitive arenas. Private enterprise propaganda concerning unfair competition from public enterprise would hardly stand up even to a “pub test” when the state was undertaking a vast amount of the basic training of workers and apprentices and also largely confining itself to natural monopolies and arenas where markets routinely fail anyway; public goods, health, welfare, aged care, education, ecological work and so on.

@ Ikonoclast,

I doubt that Bill will like this idea. He has said that any UBI or LBI is not a good idea. That the JGP is all that is required.

OTOH, I like it.

One question. Does the LBI get paid to everyone or is it stopped when people get a JGP job or private job. What about the self-employed?

Why not just have a barely livable UBI and pay it to everyone?

.

To Steve_American.

A Chinese proverb says: “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Analogously, the UBI is giving fish whereas JG is creating fishermen!

“Pay an LBI which is livable and has no work-test”

And who is going to be forced to work more hours than they need to and have that output removed from their group consumption pool to fund that? Why should those people stand for it?

The retirement pension works because there is a clear moral mechanism in place. Those who are older have created, maintained and passed on a capital inheritance that means the young don’t have to work 16 hours a day in fields growing cabbages, and that the young when they become old, will be able to request the same favour from the next generation – as long as they maintain the capital and pass it on. The young are therefore prevented from consuming all they produce and the surplus is transferred to the elderly.

It’s a system that works and self perpetuates – as long as the current generation remembers their obligations to the next. An obligation that may be fraying at present given how the young are being stitched up.

And it also means that society’s capital inheritance is already spoken for – by those who are retired.

What moral claim has an 18-year-old individual who believes the world owes them a living got against the rest working in society? They have added nothing to the pool and have no intention to.

Every income scheme fails on the supply side, not the demand side. They cannot be provisioned in any justifiable way that is sustainable over the long term.

The Job Guarantee is a macroeconomic stabiliser, not a labour market intervention. For it to work as intended it needs to be more than unemployment benefit with tweaks. It needs to be an alternative job that everybody can *choose* to be on. That’s how half the improved expectation stabilisation works. Firms know they will lose staff to the JG if they treat them badly and that stops the Uberiszation of private-sector jobs. (The other half is that low-end firms that try to raise prices face a threat from JG workers replicating that firms output – since raising prices would prevent a firm raising an “unfair competition” case against those JG workers).

Stop that movement option and jobs will all rapidly become internships via the “I earn six figures as a partner and you could too, but almost certainly won’t” trick so beloved of such operations.

MMT is as it is for a reason. The Job Guarantee is MMT’s Chesterton’s Fence.

Dear Steve_American (at 2020/10/23 at 1:30 pm)

You proposed:

There lies the issue. Why should we introduce policies that allow someone to barely live?

After all, those who argue we should accept a situation where people who can work can decline to work, even if there are sufficient jobs for all, and, instead, receive an unconditional income from the state so they can eat, drink and be merry – and be dignified members of society.

That is the line I keep hearing.

So if you want to provide a UBI that allows for dignity and a living income then it has to be relatively high – and then you are accepting that the government will use unemployment to control inflation. And the high UBI becomes an inflationary source.

If you want to avoid the inflationary bias, then you have to pay a “barely livable” UBI, which defeats the purpose.

It is far better to pay a socially-inclusive wage with all sorts of other benefits in return for work that is guaranteed by the state, which then means actual output is forthcoming, which reduces the inflation risk, allows the government to deal with inflationary pressures without unemployment and provides for a dignified existence.

best wishes

bill

Bill and everyone,

I would hope that you all understood that I saw 4 payment plans.

1] ULBI which will feed and cloth you but housing will require several roommates. No entertainment.

2] JGP, work for the Gov. at a somewhat higher total amount incl. (plus) the ULBI.

3] A private sector job plus the UBLI.

4] Retirement supplement plus the UBLI.

So Bill, I don’t see the UBLI as being anywhere near being “socially inclusive”. That is what the JGP is for.

.

Patrick B:

“Here we have The Guardian (of misleading the public on economics) today:”

Either that, or they don’t even speak with bank workers. I had an “investment consultant” say to me last week that CBs are likely to keep setting the rate low, *and* that that means inflation will be low.

Economy journalists are (for the most part) a joke with no contact with the real world.

The alphabet-soup is getting very confusing!

Two acronyms in particular:- LBI and UBI. Do the respective commenters understand them as interchangeable, or as distinct alternatives? People need to clarify that otherwise everyone just talks past everyone else. Ikonoklast seems to equate them but (sensibly) adopts the first and eschews the second when eleborating on his idea. I propose following his lead.

“There lies the issue. Why should we introduce policies that allow someone to barely live?” (Bill)

The proposal coming from one side in this debate was – in so many words – that we should allow anyone *capable* of working choosing not to work to starve to death – that being inferred to be the choice that they themselves were making when refusing to take a JG job. Neil Wilson’s comment repeats (in essence, not this time in those very words), and logically argues for, that position.

Ikonolast’s counter-suggestion was that no, we should not do that. It says that to (in Bill’s words) “introduce policies that allow someone to barely live” would be preferable. Presumably because he regards (as I do) aiming to starve them into submission as morally repugnant and indefensible, for which preserving the purity of the JG scheme cannot be accepted in a civilised society as offering a justification. Policies “that allow someone to barely live” are the minimal alternative to allowing them to die of starvation.

Neil is of course right to point out that such a policy is redistributive and that the wherewithal to fund it can therefore logically only come at some other groups’ expense – for which no *purely logical* case can be made and so which (he argues) is inequitable. But no purely logical case, only an instrumental one, can be made for progressive taxation either and that doesn’t stop many (most?) people judging it to be necessary (or at the very least expedient) based on some notion of “fairness”, or “social justice”. I don’t doubt other similar analogies can be cited. Pure logic alone has never been recognised as the sole criterion for social policies.

“After all, those who argue we should accept a situation where people who can work can decline to work … receive an unconditional income from the state so they can eat, drink and be merry – and be dignified members of society. That is the line I keep hearing”. (Bill)

– But no one here has argued that (although some may have elsewhere) –

“If you want to avoid the inflationary bias, then you have to pay a ‘barely livable’ UBI…” (Bill)

– Indeed –

“…which defeats the purpose.” (Bill)

– Does it?

(I can’t see which purpose, or how).

“The Job Guarantee is a macroeconomic stabiliser, not a labour market intervention”. (Neil Wilson)

If that’s to be taken at face-value it means that an awful lot of what I’ve been taking away from Bill’s blog over all these years either has been wrong or I’ve completely failed to understand it. To my eyes, the JG is clearly both.

If transforming the existing labour-market buffer stock from one consisting of involuntarily unemployed people to one consisting of people employed at a living wage plus benefits package is NOT “a labour market intervention” then what would an actual “labour market intervention” look like?

What then is to become of individuals who cannot work? Will even a public sector JG leave them by the wayside, struggling to cope with the grinding poverty, regular sanctioning to throw them off benefits on a repeated basis, and the vicious demonisation we here in the UK have consigned them to suffer at present?

@Valerie Leppard

Individuals who cannot work would receive the disability pension, as they do now. Hopefully we will see a more compassionate system in future. The JG would also allow for those who can only work part-time.

” based on some notion of “fairness”, or “social justice””

There is no basis for “distributive justice” because that is already used up on the retirement pension as I’ve shown. The ‘minimal gift’ (to use Van Parijs term) is from the young to the old for what they have bequethed to them. Therefore what is suggested is that younger people should get the income instead of the older ones, or that somebody in between should get still less.

At that point the argument is that those who do things and those who have done things should be forced by law to support those who unreasonably refuse to do anything. Unsurprisingly the majority do not see that as fair, reasonable or fitting any notion of distributive justice.

Which is one of the reasons why all basic income schemes ultimately fail. They simply aren’t fair.

Responding to Valerie Leppard’s comment: obviously a job guarantee is irrelevant for someone who cannot work.

If a society chooses to support its members who cannot work, that support must be given some other way.

How much support, and how to provide it, are ethical and practical questions that a society should consider and answer.

Personally I agree with Valerie’s view of the current system in the UK: it is barbaric.

An unconditional basic income would also be a bad way to support people who cannot work: they would be among those with the very smallest income (since they cannot add to that income through wages).

If you want Bill’s opinion, in several blog-posts he has stated his view that we should pay a disability pension. I don’t know if he has said anything explicit about how much it should be, but it is implicit in his frequent statement that a Job Guarantee job should pay a full-time worker a “socially inclusive” level of income that provides for a material standard of living that society agrees should be available to everyone.

Therefore implicitly, Bill’s stated views can be combined to mean that someone unable to work should receive a level of income (or income plus other kinds of support or services) that provide that same material standard of living.

In the UK, the Living Wage Foundation calculates the (real) Living Wage based on the costs of “budgets for different household types, based on what members of the public think you need for a minimum acceptable standard of living in the UK,” (research done for the Minimum Income Standard). This consensus-based way of setting it fits very well with what Bill has said about setting the level of a “socially inclusive” income.

Personally, I think everyone should have access to that “minimum acceptable standard of living” so the payment to a working-age person who cannot work should be at least equivalent to the income from full-time work in a Job Guarantee job.

Also, some people have to pay extra to reach that same material standard of living, whether or not they are working or can work. For example, people with impaired mobility use taxis, transplant patients with immunosuppressants do extra cleaning/disinfecting and water-heating, some people can walk fine but only if they have expensive custom-made orthopaedic shoes… so there should be something similar in concept to the existing Personal Independence Payment scheme but broader and enough to cover the realistic extra costs.

“Which is one of the reasons why all basic income schemes ultimately fail. They simply aren’t fair”. (Neil Wilson)

(I’m sure I recall that somewhere quite recently you went on record dismissing a comment which had been based on fairness made by someone else by saying (in effect) that fairness was not a valid criterion (i forget why – perhaps because it’s too subjective?). Trying to find that reference is like looking for a needle in a haystack so I’ve given-up. But I’m sure you’ll remember it).

Anyway, my point is (putting it at its most platitudinous) that “*life* isn’t fair” – as most people find themselves exclaiming at some point(s) or other in their own lives. Some “undeserving” people are just lucky and some “more deserving” just unlucky. That’s how it is.

I don’t believe that issues of social policy are susceptible to being resolved by the use of some kind of calculus such as you are using, which purportedy delivers a precise, ineluctable “result”. To do so you isolate just two or three elements from all of their contextual complexity as if in a laboratory experiment. I readily concede that doing that can have a powerful effect in disciplining what might otherwise tend to be woolly thinking – and as such does have its uses. What I disagree with is then taking its outcome and applying it – still in complete isolation – to the real, much more multifarious and interdependent actually-existing human society from which you abstracted it in the first place, as if it alone were a sufficient guide to the making of policy-choices. It most decidedly isn’t, IMO.

Although there are other points in your post I’m tempted to take you up on, I won’t because it’d be fruitless (and probably boring) to do so. I suspect that we would never reach agreement, regardless.

Has anyone got any specific data on BoE buying of gilts to control interest rates, how much it is putting debt on its own books.

“Has anyone got any specific data on BoE buying of gilts to control interest rates, how much it is putting debt on its own books”

The Asset Purchase Facility is the BoE subsidiary that does all that. Here’s the latest Quarterly report

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/asset-purchase-facility/2020/2020-q2