It's Wednesday and we have discussion on a few topics today. The first relates to…

Why improve policy when a government can pillory a low-paid, precarious worker instead

Last week we saw further evidence of the way in which class divisions create havoc for society although the way these events have been constructed in the media and popular perception are the antithesis of what was really going on. After having no coronavirus cases since April 16, 2020, suddenly we were informed on Sunday, November 15, 2020, that a dangerous virus cluster had emerged in South Australia (in particular the capital Adelaide) as a result of a breach in quarantine. The memories of Victoria’s second wave, which had started as a result of a similar breach came flooding back and the South Australian state government almost immediately imposed a very harsh 6-day lockdown (the most restrictive imaginable). The following day, amidst all the furore about the severity of the restrictions, the Government announced they were rescinding the orders (mostly). Why? Because some foreign worker had contracted the virus had lied to investigators about his status and was, in fact, working at both the quarantine hotel where the breach occurred and a pizza shop were additional cases had been detected. Apparently this ‘lie’ led to the severe lockdown because it created some uncertainty in transmission links. I doubt that was the case and I think the Government just overreacted and lacked confidence in their own systems. But now it is the ‘lie’ that everyone is focusing on and the Premier is threatening to ‘throw the book’ at the individual. Not many questions are being asked in the media about the poor systems that led to the breach in the first place nor the overreaction of the government. All attention is being focused on a casualised, precarious worker who was forced to work (at least) two jobs to survive. There lies the issue.

I have been reading the research output that is starting to come out linking the incidence of Covid-19 and the resulting deaths to socio-economic status.

There are numerous studies which support the conclusion that individuals from the more disadvantaged socioeconomic groups endure worse health (mental and physical), higher rates of illness and disability, and, die earlier than those from better-off backgrounds.

This phenomenon is referred to as the ‘social gradient of health’, which the World Health Organization defined as (Source):

The poorest of the poor, around the world, have the worst health. Within countries, the evidence shows that in general the lower an individual’s socioeconomic position the worse their health. There is a social gradient in health that runs from top to bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum. This is a global phenomenon, seen in low, middle and high income countries. The social gradient in health means that health inequities affect everyone.

So during a pandemic such as we are living through at present, this phenomenon has intensified.

An interesting US-study published on June 15, 2020 – Poverty and Covid-19: Rates of Incidence and Deaths in the United States During the First 10 Weeks of the Pandemic – by W. and M. Finch, sought to examine how poverty incidence intersected with Covid-19 incidence and death.

They found an interesting evolution of the virus incidence:

… that during the early weeks of the pandemic more disadvantaged counties in the United States had a larger number of confirmed Covid-19 cases, but that over time this trend changed so that by the beginning of April, 2020 more affluent counties had more confirmed cases of the virus.

This indicates that ultimately communities are interlinked in various ways, and, while the better-off citizens can insulate themselves from the rest in many ways, ultimately, they too become vulnerable in a disaster of this scale.

However, as the pandemic ensued “the number of deaths was greater in areas of relatively greater poverty”:

Furthermore, a larger number of deaths was associated with a larger percent of county residents living in poverty, living in deep poverty, a higher incidence of low weight births, and with the county being designated as urban.

So while, eventually, the better-off neighbourhoods experienced sickness, they were able to access superior health care which reduced the death rate.

However, the authors are clear that the data deficiencies (particularly poor testing rates in poorer communities) may be hiding the incidence in the more disadvantaged communities.

The Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion – at Syracuse University provides some interesting US-based data that is relevant.

One study (April 1, 2020) – Data Slice Issue Number 15 – found that:

… testing rates to date have been lower in states with higher percent black populations and higher poverty rates … For example, whereas the average COVID-19 testing rate in states with the lowest percent black populations (bottom 25th percentile of percent black) is 403.5 per 100,000 population, the average rate among states with the highest percent black populations (top 25th percentile) is only 206.4 per 100,000 population.

The reliance on public transport is also a factor.

This US study published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (Vol 69, Issue 12) – Associations between individual socioeconomic position, neighbourhood disadvantage and transport mode: baseline results from the HABITAT multilevel study – found that:

… the odds of using public transport were higher for white collar employees … members of lower income households … and residents of more disadvantaged neighbourhoods …

But attenuating that tendency for white collar workers was the increased capacity to ‘work from home’ during the pandemic, thus severing their reliance or propensity to be exposed to disease on public transport.

In the US context, the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics – America Time Use Survey – reveals that:

1. “24 percent of employed persons did some or all of their work at home”.

2. “Workers employed in management, business, and financial operations occupations (37 percent) and workers employed in professional and related occupations (33 percent) were more likely than those employed in other occupations to do some or all of their work from home on days they worked.”

3. “Among workers age 25 and over, those with an advanced degree were more likely to work at home than were persons with lower levels of educational attainment”.

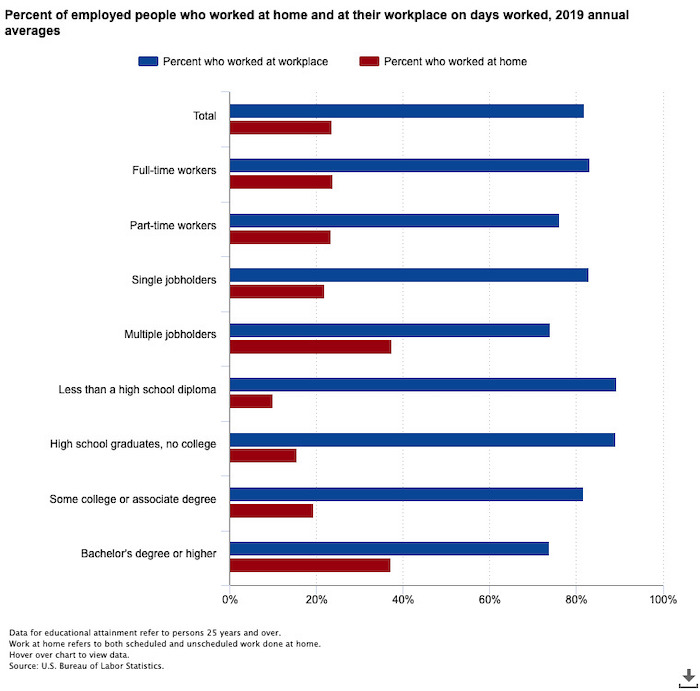

The following graphic compiled by the BLS is telling.

These trends are mirrored elsewhere.

Research published by Roy Morgan Surveys for Australia on June 29, 2020 – Nearly a third of Australian workers have been ‘#WFH’ – shows that:

1. “There are also significant differences between people working in different industries. Over half of people working in Finance & Insurance (58%) and Public Administration & Defence (51%) have been working from home and just under half of those in Communications (47%).”

2. “Far less likely to be working from home are Australians working in more ‘hands-on’ industries. Fewer than one-in-six Australians working in Manufacturing (16%), Transport & Storage (15%), Agriculture (13%) or Retail (12%) have been working from home during the last few months.”

Then we have to also consider the lockdown bias across socioeconomic groups.

Amnesty International released an interesting report (June 24, 2020) – Europe: Policing the pandemic: Human rights violations in the enforcement of COVID-19 measures in Europe – provides another dimension to this issue.

They found that:

1. “The police enforcement of lockdowns disproportionately impacted poorer areas, which often have a higher proportion of residents from minority ethnic groups.”

2. “In Nice, nine predominantly working class and minority ethnic neighbourhoods were subjected to longer overnight curfews than the rest of the city.”

3. “police in London registered a 22 percent rise in stop and searches between March and April 2020. During that time the proportion of Black people who were searched rose by nearly a third.”

4. “During mandatory quarantines in Bulgaria over 50,000 Roma were cut off from the rest of the country and suffered severe food shortages.”

The gig economy and the ‘lying’ worker

I have wrote about this theme in several past blog posts including:

1. The coronavirus crisis is just exposing the failure of neoliberalism (May 12, 2020).

3. The coronavirus crisis – a particular type of shock – Part 2 (March 11, 2020).

4. We are all entrepreneurs now marching towards a precarious and impoverished future (June 4, 2019).

5. Why Uber is not a progressive development (August 16, 2016).

6. The New Economy cannot flourish with fiscal austerity (May 31, 2012).

An increasing numbers of workers now rely on precarious employment situations for their incomes.

They rely employment through apps without the normal protections, without proper pay, and so on.

Neoliberalism clearly subjugates human development and opportunity to the interests of profit.

It has created a ‘Just-in-Time’ culture in manufacturing, in work (the gig economy), in our personal finances (debt vulnerability) as part of the deliberate strategy to gain a greater share of national income for profits at the expense of workers.

Only 60 per cent of Australia’s workforce is engaged in full-time or permanent part-time employment.

The most recent ABS – Characteristics of Employment, Australia – data as at August 2019 (next release for 2020 is due in December) shows that there are around 25 per cent of workers without paid-leave entitlements, which in the Australian context is often an indicator of ‘casual’ status.

This ABC Fact Check (March 30, 2020) – COVID-19 has put jobs in danger. How many workers don’t have leave entitlements? – explores the data in some detail.

These workers are concentrated in industry sectors that have been severely impacted by the Covid-19 policy responses – hospitality, retail trade, tourism, cleaning, food services etc.

The sectors that enjoy much lower rates of casualisation also tend to have higher capacity for workers to work from home.

So the least-paid, most precarious workers are those that are less able to work from home.

Which brings us to the way the individual pizza worker in Adelaide has been pilloried by the politicians and the smug, well-paid health authories for apparently lying about his work status.

The South Australian premier claimed at his press conference last Friday where he announced the backdown on the severe lockdown, that:

To say I am fuming about the actions of this individual is an absolute understatement. The selfish actions of this individual have put our whole state in a very difficult situation. His actions have affected businesses, individuals, family groups and is completely and utterly unacceptable.

The reality is that while they can claim that the “selfish actions of an indvidual” may have led to the Government’s decision to invoke a rather harsh lockdown, the fact that a low-paid precarious worker found the need to ‘lie’ is an indication of a much larger issue in Australian society.

Policy makers have allowed a situation to develop where desperation rather than hope drives action.

First, they have deregulated the labour market to allow employers much more power.

Second, they allowed the wage setting bodies to reduce penalty rates for non-standard work in already low-paid occuptions.

Third, governments have been reluctant to offer income insurance (that is, pay wages) for workers who are forced into isolation and/or quarantine because they test positive or are a close contact to someone else who tests positive.

The incentives have not been provided to precarious workers to do the right thing by all of us to stay away from work and public transport.

It would have been so easy for the Federal government to implement as scheme offering 100 per cent income protection, which would have eliminated the incentive to evade the lockdown rules, resist testing and not disclose to contact teams the full details.

Once again this failure by government is an example of the myopia of neoliberalism.

See this blog post (among others) – The myopia of fiscal austerity (June 10, 2015).

Interestingly, the Victorian government did introduce a partial scheme in this regard, which helped. But it should have been implemented more generously and by the currency-issuing federal government.

Further, today (November 23, 2020), the Victorian Premier said that “the idea of providing paid sick or carer’s leave to workers had benefits beyond the lifespan of the pandemic” (Source).

He said:

The Commonwealth government are well aware of our views around insecure work and the fact that it’s neither fair nor safe. It’s neither profitable nor in any way sustainable. We can’t continue to ignore this as a nation. I don’t have those levers though.

QED.

Fourth, when the pandemic hit, the federal government refused to support financially more than a million casual workers, despite providing a wage subsidy to other workers. The workers excluded from the JobKeeper program were those who could not show a continuous work association with their employment over the last 12 months.

That, of course, was a deliberate policy choice to reduce government spending given they know that a characteristic of that segment of the labour market is a definite lack of on-going work.

Casual workers cycle between stints of precarious work and joblessness continually. At least a million workers were thus excluded.

Fifth, the South Australian government chose to put private, untrained security firms in charge of the quarantine hotels they have set up to provide a barrier between infected, returning travellers and the rest of us.

They clearly didn’t learn from Victoria, which made the same mistake that led to the second wage.

It turns out that a casual, untrained security guard at one of the hotels became ill with Covid-19. He also worker at a pizza bar as a second job.

The gig economy is characterised by workers having to work multiple jobs to make enough income to survive.

The data shows that more than 2.1 million workers in Australia (around 15.6 per cent) work in multiple jobs to make ends meet and that proportion is steadily rising (Source).

And these workers are concentrated in health care, social assistance, education and training, administration, accommodation and food services, and retail trade.

The usual suspects.

Women and migrants, who face discrimination in the labour market.

Survey evidence shows the motivation is “income stability”.

Another worker, who also was a casual guard at another quarantine hotel also contracted Covid-19 told the contract tracers that he had bought a pizza at a the shop the other infected worker worked.

The Government thus concluded (why? they don’t say) that the virus outbreak was very serious and they went into overdrive (read: overeaction), even banning people from exercising outdoors, which Victoria (with very bad second wave) resisted invoking for obvious physical and mental health reasons.

Then a day later, the Premier’s press conference. Egg on face. They had to blame someone.

So this second casual worker – low paid and precarious – had lied to them. He actually worked at the same pizza bar as the other guy rather than being a casual customer.

Lockdown revoked.

Police turn on the worker promising to throw the book at him.

Not only that, social media vigilantes announced a boycott of the pizza bar (the gutless heroes on Twitter and Facebook), which just happens to be located in one of Adelaide’s disadvantaged suburbs where deindustrialisation has impacted on employment and household income and many migrant workers live.

The Premier might feel happy about turning the savages on a low-paid, precarious worker but has refused to explain why they used casualised, untrained labour to oversee the security systems for the quarantine hotels, where the outbreak actually started.

The fact that the worker didn’t admit that he was working two jobs is one thing that might have thrown the investigation a little.

But using him in a high risk situation such as the quarantine arrangements, where he had to work two jobs to make ends meet is more the issue.

And why didn’t the government have a regular testing regime in place for such quarantine workers?

Silence from the authorities.

Conclusion

The pandemic is exposing many things about contemporary society.

But above all, it is showing us that the trend to the gig economy and increasing precarity of work is a danger to us all.

The problem is that there is scant regard among the policy makers to make changes that provide less vulnerability.

The South Australian government’s response is classic – blame the victim of a systemic crisis, created by – government.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I thought the same thing – scapegoating one person.

If their system is so fragile that it cannot handle one error/bad input, then it has been designed badly.

Seems weird that you wouldn’t employ quarantine guard on a full time basis, and make it a condition of exclusive employment. Or at a minimum that a guard needs permission to take up employhment elsewhere…

I see the Tories “froze” public sector wages.

I watched Randy Wray’s interview with Centre for the study of financial innovation. Randy seemed to think there will be some price increases for some goods and services. They will vary from sector to sector due to the virus.

Since the minimum wage has gone from £7.20 in Apr 2016 to £8.21 in April 2019. In April this year it will go to £8.72

Was that the correct policy choice.?

Did they “freeze” public sector wages so that they didn’t have to cancel the min wage increase in April ?

Or was it purely ideological.

So I suppose the debate is.

Was it right to ” freeze” public sector wages in order to increase the min wage in April to £8.72

Was it due to fear of price increases like Randy pointed out ?

Was it ideological driven ?

Or could they have increased both the min wage in April and public sector wages at this time and not worry about prices ?

Or

Increased public sector wages and left the minimum wage where it was ?

Derek:

‘Average earnings in both the public and private sectors remain below precrisis levels. Public sector earnings did not fall immediately during and after the

Great Recession, but significant pay restraint after 2010 reduced average public

sector earnings in 2014 Q2 to 4.7% below their level at the start of 2008. Public

sector earnings have risen by around 2% in real terms since the end of 2017, but

are not yet back to pre-crisis levels. ‘ (https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN263-public-sector-pay-and-employment1.pdf)

About a million of these workers (5 million in all?) have wages considered below ‘living wage.’ (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/28/public-sector-workers-living-wage-in-work-poverty-report)

There has also been a massive fall in n umbers working for local Government in the last ten years in the UK (drop of 840,000) and in increase in Central Government (‘The State Never Went Away’ 🙂 )

Can’t see it can be anything but ideological if by ‘non-ideological’ you means some ‘objective’ measure of likely spending patterns that could be inflationary given supply/resource issues. Not that I have any understanding of how that is playing out at present.

Looks like the Tories seem to be able to throw money at corporate buddies and will also throw money at the Red Wall areas while local Government goes bankrupts in other parts of the country.

Thank you, Bill, for again highlighting what are commonly called “BS jobs,” the ones that replaced the decent jobs prevalent during the first half of my life. Here’s a key line from Bill’s post: “It would have been so easy for the Federal government to implement a scheme offering 100 per cent income protection, which would have eliminated the incentive to evade the lockdown rules, resist testing and not disclose to contact teams the full details.” How tragic is it that enough people do not yet understand MMT and thus cannot see how “easy” this could have been…and still is?

In Canada the rate of infection with covid-19 is 270 times greater than what Australia is currently experiencing.

Between late October and May the weather here drives nearly everything indoors, away from sunshine and fresh air; so we are well into a 6 month period of perfect conditions for the virus to spread.

The province were I live, has the second highest cumulative number of cases in a country seeing exponential growth in infections.

Our experience has been that lock down measures implemented late last winter and spring, made a difference, though not as much as warm summer weather.

Highest rates of infection had been mostly confined to just a few areas were there was a combination of high population density and and higher numbers of working poor; however, we are seeing spillover from those places to areas that were previously spared the worst.

In my vicinity the return of large numbers of post secondary students, was followed by a significant rise in community infection rates.

Interestingly, most undergraduate education has gone on line since the beginning of the fall semester, yet many of the students continue to roam in groups around the town, unwilling to let go the leases on near campus living space, and social life.

Many of the working poor are employed in occupations deemed “essential” by the federal government, and many of those are recent immigrants living in close quarters with extended family. As such these people do not have the option of staying at home collecting a passive income from the government or working from home, so it remains to be seen how effective the current new lock down measures will actually be in those areas .

Many small to medium size businesses are collapsing since government will subsidize the rents paid by business to landlords, yet offer little in the way of help for the businesses themselves, who are now struggling to find new ways to operate.

The recent return of mainstream media attention to declining socioeconomic conditions and growing criticism of neoliberal policy as a root cause, pulled to front and center by this virus, has been heartening.

Left wing politicians are now also beginning to test the waters to see if they can gather greater support for progressive causes, and they are, as the existence of glaring structural failures caused by neoliberal driven policy become evident to all.

Re J. Christensen.

I’m from Canada too and it is as you say altho I’d add that the federal government has offered to subsidise workers wages, but as you note not subsidise businesses directly (except the airline industry it looks like).

I’m currently in Nova Scotia where the infection rate is very low. Nova Scotia is part of the Atlantic bubble. Everyone coming in, including other Canadians, must do 14 days of quarantine, not leave and have no visitors. We recently emerged. Wow the world is big!

The usual debt/deficit mongers are mostly subdued but their avant-garde, the CD Howe Institute, is predicting disaster. CD Howe is mostly financed by the banks so we know what’s coming, but not yet. Hopefully the federal government will get a few large public programs in place before the full-on bank/conservative response arrives.

In 2015 Justin Trudeau shocked the country by proposing a $10 billion deficit (0.5% of GDP!) during the election campaign. It was very daring. And he won. This year the deficit is projected to be at least $343 billion, funded by the Bank of Canada of course. Hopefully progressive groups and politicians will be able to use this to argue in favour of generous social programs, job creation, green jobs, etc. Not so sure though. The allure of household finance arguments remains strong.

I love how they blame the person who has to work TWO JOBS when there is a deadly virus about.

The social gradient of health is an important point.

The inequality of exposure of poor people is also important and happened to us at our university.

Upon reflection, I think poor people know that they are being screwed and it is in their interest for an overhaul. All these theories are invented to convince the middle class to get off the couch.

To be fair to the South Australian Government, this person claimed he’d contracted Covid-19 by merely picking up a pizza and that he had done so just days before testing positive.

The authorities may have over reacted but it looked like they had a super-spreader event on their hands and a strain of the virus that incubated far more quickly then normal. All of which added up to a contact-tracing nightmare! An abundance of caution demands you go into full lock-down under these circumstances until the facts came to hand.

What I find extraordinary is that the proprietor of this pizza parlor must have been asked to supply a list of his/her employees to the authorities and I suspect this guy’s name wasn’t on it!

This is flip side of neoliberalism. Small businesses that will not admit that someone works for them when it really matters. How many regulations were being breached in this case I wonder?

The Guardian Australia is currently running a series on food delivery operatives who have died (usually in motor vehicle accidents) delivering orders to customers. Naturally, most of them are recently arrived migrants struggling to make ends meet.

This marginalized “Gig” economy is a “putting-out system” with a vengeance!

Why Jimmy Barnes (aka Australia’s beloved “Working Class Man”) is currently featuring in adverts for Uber Eats is beyond me!