Today (February 21, 2023), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Wage Price…

Real wages in Australia continue to go backwards

Last week, two major wage data releases came out from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. On Wednesday (February, 24, 2021), the – Wage Price Index, Australia – which was followed on Thursday (February 25, 2021) by the latest – Average Weekly Earnings, Australia. The two series are quite different as I note below. Both demonstrate poor wages outcomes in Australia. The ABS reported that Australia “maintained the historically low annual growth rate of 1.4 per cent for a second quarter” and that the data “showed a large proportion of the private sector wage growth came from the continued restoration of hourly wages back to pre-pandemic levels”. In other words, the cuts firms got away with last year were restored, which is a different thing to on-going growth. Private sector grow was just 0.7 per cent and public sector growth was just 0.3 per cent. The overall WPI growth was just 0.6 per cent. The public sector is clearly not demonstrating leadership with their ridiculous wage freezes and wage caps stifling wages growth not only in the public sector but also via the spillover effects to the private sector. With the quarterly inflation in the December-quarter was recorded at 0.22 per cent, real wages thus rose for Australian workers. But if we consider the annual movements private sector wages grew by 1.4 per cent while annual inflation (excluding volatile items) was 1.5 per cent, so real wages fell over the year to December 2020. Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.

The summary results (seasonally adjusted) for the December-quarter 2020 were:

- The Wage Price Index grew by 0.6 per cent in the December-quarter 2020 – the lowest on record, and 1.4 per cent over the previous 12 months – static.

- The growth for the private sector was 0.7 per cent in the December-quarter and 1.4 per cent over the year – slight acceleration.

- The growth for the public sector was 0. 3 per cent in the December-quarter and 1.6 per cent over the year – slowing.

To clarify, the Wage Price Index:

… measures changes in the price of labour, unaffected by compositional shifts in the labour force, hours worked or employee characteristics

While Average weekly earnings is:

… designed to measure the level of average earnings in Australia at a point in time. Movements in average weekly earnings can be affected by changes in both the level of earnings per employee and in the composition of the labour force. Factors which can contribute to compositional change include variation in the proportion of full-time, part-time, casual and junior employees; variation in the occupational distribution within and across industries; variation in the distribution of employment between industries; and variation in the distribution of hours worked and paid for.

So the former nets out compositional impacts that can provide misleading inferences.

I won’t analyse the AWE series but the main conclusions were:

1. “The average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time adults in Australia in November 2020 was $1,712 (seasonally adjusted), down 0.1 per cent from May 2020”.

2. “The fall in average earnings in November highlights the extent of recovery in low paid jobs, hours and earnings since May. While the recovery has varied by industry and other factors, there has been enough recovery at the lower end of the distribution to put downward pressure on the average.”

Nominal wage and real wage trends in Australia

The ABS Media Release – said that:

The … Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.6 per cent in December quarter 2020 and maintained the historically low annual growth rate of 1.4 per cent for a second quarter … December quarter’s moderate growth was influenced by businesses rolling back short-term wage reductions, returning wages to pre-COVID levels.

In original terms, wages rose 0.5 per cent in December quarter 2020. Private sector wages rose 0.5 per cent, outpacing the public sector rise of 0.3 per cent. Wage freezes have had an impact on the public sector which recorded its lowest annual increase (1.6 per cent) since the commencement of the series.

So no actual growth, just a return of the cuts the firms got away with during the worst days of the pandemic.

The data tells us that On an annualised basis:

| Measure | Quarterly (per cent) | Annual (per cent) |

| Private hourly wages | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Public hourly wages | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Total hourly wages | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| Basic CPI measure | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Core inflation excluding volatile items | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Weighted median | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Trimmed mean | 0.3 | 1.2 |

Which means that depending on which inflation measure is used, real wages rose over the December-quarter (but only because wage cuts earlier in the year were restored as the economy recovered).

But over the year to the December-quarter they fell, were static or rose slightly for both public and private employees.

On price inflation measures, please read my blog – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

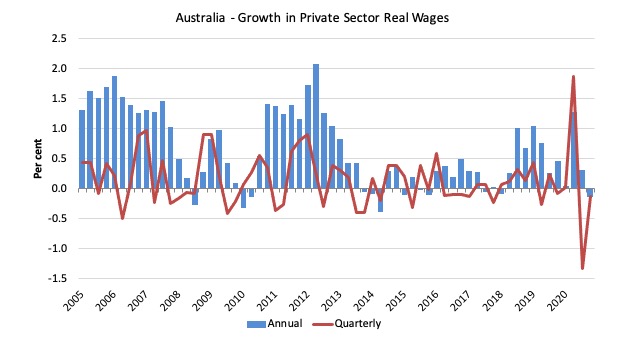

The first graph shows the growth in private sector real wages since the March-quarter 2005 to the December-quarter 2020. The Core inflation measure excluding volatile items is used.

The blue bars are the annual rate of change, while the red line is the quarterly rate of change.

The fluctuation between the June- and September-quarters result is an outlier – given the temporary government decision to offer free child care for the June-quarter which was rescinded in the September-quarter.

The record is appalling since 2013.

Throughout 2017 and into 2018, real wages growth was negative. But then there were several quarters of modest real wages growth. The trend, however, is towards zero real wages growth.

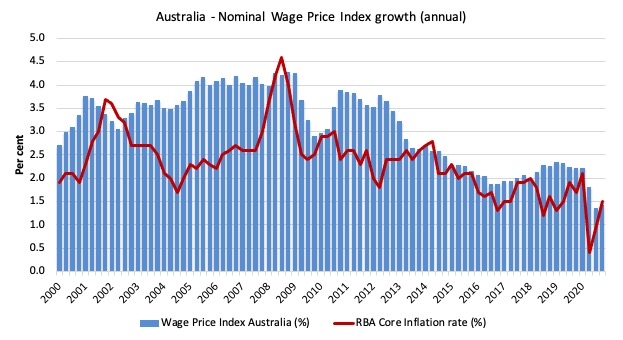

The next graph shows the overall annual growth in the Wage Price Index (public and private) since the December-quarter 2000 (the series was first published in the December-quarter 1997).

I also superimposed the RBA’s core annual inflation rate (red line). The blue bar area above the red line indicate real wages growth and below the opposite.

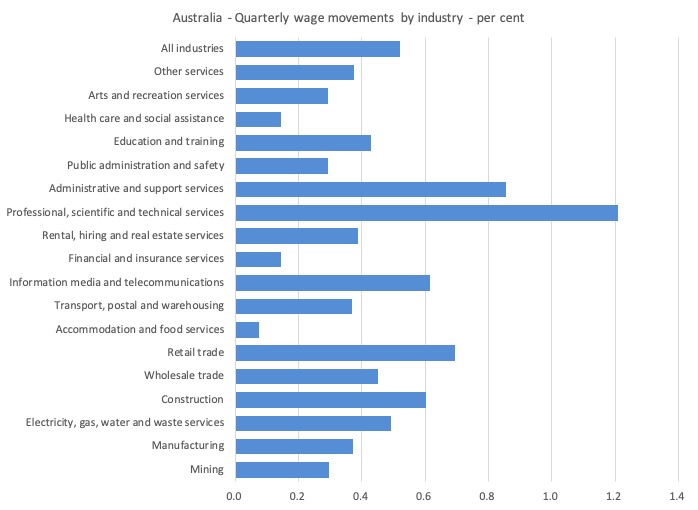

Sectoral Variability

The aggregate data shown above hides quite a significant disparity in quarterly wage movements at the sectoral level, which are depicted in the next graph.

The ABS also reported that:

Professional, scientific and technical services recorded the highest quarterly rise of 1.2%, following a fall in June quarter 2020 and moderate growth in September quarter 2020. The main driver of this industry’s wages growth was the unwinding of short-term wage reductions to previous wage levels …

Accommodation and food services recorded the lowest annual rise of 0.3%. Modern Award increases were the main driver of the annual growth although the timing of these increases has changed. Growth usually seen in the September quarter for this industry, is now scheduled for February 2021 due to the phased implementation schedule of Fair Work Commissions award increases.

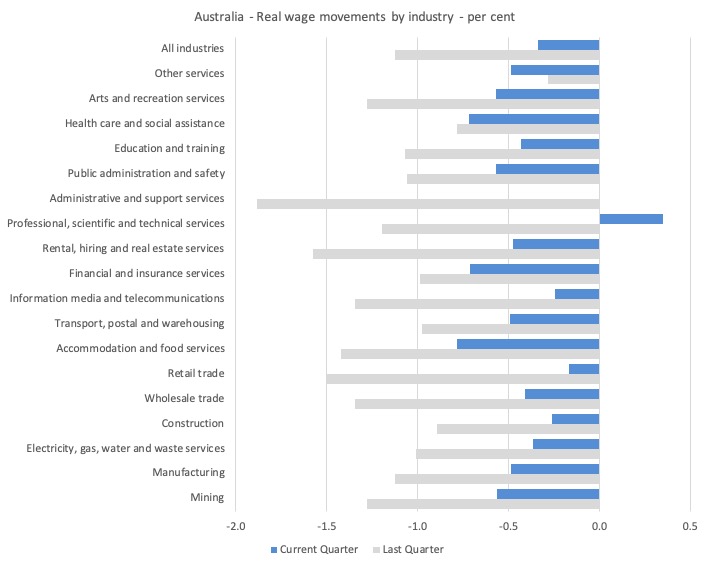

While nominal wages growth was mostly positive, albeit modest, the next graph shows the movements in real wages and you can see that workers in all occupational groups lost purchasing power in the December-quarter other than those in Professional, scientific and technical services, and that was only a rebound on previous cuts.

Workers not sharing in productivity growth

The Non-farm GDP per hour data (productivity) is derived from the quarterly National Accounts and available via the RBA Table H2 Labour Costs and Productivity.

The ABS Information Note: Gross Domestic Product Per Hour Worked – says that:

In Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (cat. no. 5206.0) and Australian System of National Accounts (cat. no. 5204.0) the term ‘GDP per hour worked’ (and similar terminology for the industry statistics) is generally used in preference to ‘labour productivity’ because:

– the term is more self-explanatory; and

– the measure does not attribute change in GDP to specific factors of production.

While real wages growth means that the rate of growth in nominal wages is outstripping the inflation rate, another relationship that is important is the relative growth of real wages and productivity.

Historically (for periods which data is available), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards.

In effect, productivity growth provides the ‘space’ for nominal wages to growth without promoting cost-push inflationary pressures.

There is also an equity construct that is important – if real wages are keeping pace with productivity growth then the share of wages in national income remains constant.

Further, higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth then spawned new activity and jobs, which absorbed the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

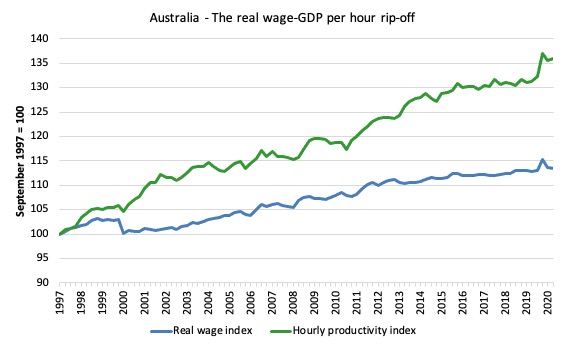

Taking a longer view, the following graph shows the total hourly rates of pay in the private sector in real terms (deflated with the CPI) (blue line) from the inception of the Wage Price Index (December-quarter 1997) and the real GDP per hour worked (from the national accounts) (green line) to the December-quarter 2020.

It doesn’t make much difference which deflator is used to adjust the nominal hourly WPI series. Nor does it matter much if we used the national accounts measure of wages.

But, over the time shown, the real hourly wage index has grown by 13.4 per cent, while the hourly productivity index has grown by 36 per cent.

So not only did real wages decline in the December-quarter, the growth in productivity widened the gap between the two series even further.

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the gap would be much greater. Data discontinuities however prevent a concise graph of this type being provided at this stage.

For more analysis of why the gap represents a shift in national income shares and why it matters, please read the blog post – Australia – stagnant wages growth continues (August 17, 2016).

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Mostly to profits.

Now, if you think the analysis is skewed because I used GDP per hour worked (a very clean measure from the national accounts), which is not exactly the same measure as labour productivity, then consider the next graph.

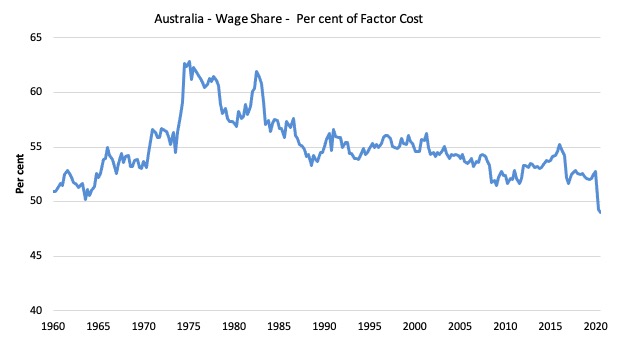

It shows the movements in the wage share in GDP (at factor cost) since the March-quarter 1960 to the September-quarter 2020.

The only way that the wage share can fall like this, systematically, over time, is if there has been a redistribution of national income away from labour.

I considered these questions in a more detailed way in this blog post series:

1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 1 (November 20, 2019).

2. 1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 2 (November 21, 2019).

And the only way that can occur is if the growth in real wages is lower than the growth in labour productivity.

That has clearly been the case since the late 1980s. In the March-quarter 1991, the wage share was 56.6 per cent and the profit share was 22.2 per cent.

By the September-quarter 2020, the wage share had fallen to 49 per cent and the profit share risen to 31.1 per cent.

A massive redistribution of income towards profits has occurred over the last 40 years.

The relationship between real wages and productivity growth also has bearing on the balance sheets of households.

One of the salient features of the neo-liberal era has been the on-going redistribution of national income to profits away from wages. This feature is present in many nations.

The suppression of real wages growth has been a deliberate strategy of business firms, exploiting the entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment over the last two or three decades.

The aspirations of capital have been aided and abetted by a sequence of ‘pro-business’ governments who have introduced harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce the trade unions’ ability to achieve wage gains for their members. The casualisation of the labour market has also contributed to the suppression.

The so-called ‘free trade’ agreements have also contributed to this trend.

I consider the implications of that dynamic in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009).

As you will see, I argue that without fundamental change in the way governments approach wage determination, the world economies will remain prone to crises.

In summary, the substantial redistribution of national income towards capital over the last 30 years has undermined the capacity of households to maintain consumption growth without recourse to debt.

One of the reasons that household debt levels are now at record levels is that real wages have lagged behind productivity growth and households have resorted to increased credit to maintain their consumption levels, a trend exacerbated by the financial deregulation and lax oversight of the financial sector.

Real wages growth and employment

The standard mainstream argument is that unemployment is a result of excessive real wages and moderating real wages should drive stronger employment growth.

As Keynes and many others have shown – wages have two aspects:

First, they add to unit costs, although by how much is moot, given that there is strong evidence that higher wages motivate higher productivity, which offsets the impact of the wage rises on unit costs.

Second, they add to income and consumption expenditure is directly related to the income that workers receive.

So it is not obvious that higher real wages undermine total spending in the economy. Employment growth is a direct function of spending and cutting real wages will only increase employment if you can argue (and show) that it increases spending and reduces the desire to save.

There is no evidence to suggest that would be the case.

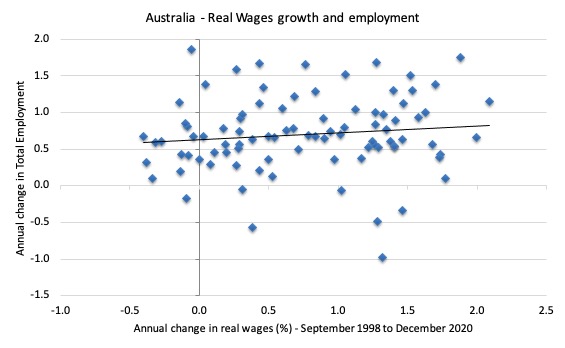

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages (horizontal axis) and the quarterly change in total employment (vertical axis). The period is from the December-quarter 1998 to the December-quarter 2020. The solid line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: When real wages grow faster so does employment although from a two-dimensional graph causality is impossible to determine.

However, there is strong evidence that both employment growth and real wages growth respond positively to total spending growth and increasing economic activity. That evidence supports the positive relationship between real wages growth and employment growth.

Noting that we should not draw causality from two-dimensional cross plots.

Conclusion

In the December-quarter 2020, Australia’s wage growth continued to struggle at record low levels.

There can be no sustained recovery for the economy post Covid without a significant shift in the way we think about wages growth.

The business sector, as a whole, thinks it is clever to always oppose wages growth and the banks love that because they can foist more debt onto households to maintain their consumption expenditure.

But the wheels are falling off the whole show and the pre-Covid imbalances between wages and profits have not been addressed.

The problem is that the federal government supports wage suppression because that attracts funding for the conservatives from the corporate lobbies which help them stay in power.

It is a pretty bleak outlook for workers.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Spreading the word.

Here is an intro to MMT I wrote for the journal of the 40,000 member- strong NSW Public Service Association. (The editor went with a bit of money printing vibe with the graphic but it was out my hands).

https://psa.asn.au/the-end-of-austerity/

Public sector workers seem a natural support base for MMT ideas. They are facing years of zero wage growth as we pay down the national credit card for the sake of our children’s grandchildren etc…etc.

There is an article on MMT by Ross Gittins in The Age. It’s not good.

Gittins:

“If you give a bunch of vote-buying politicians a licence to spend as much as they like up to a certain point, how could you be sure they’d stop, and revert to borrowing, when they reached that point?”

The alternative (which we’ve endured for 40 years and we must assume Gittins prefers) is to have a bunch of totally “bought” politicians enacting policy that ensures something like 5% of the workforce is permanently mired in unemployment.

Dear Allan (at 2021/03/01 at 2:16 pm)

It is moronic. I invited Gittins as a guest speaker at one of the CofFEE Conferences that I used to run. It was about 18 years ago and he got up and canned our work raving on about inflation. He knows where MMT comes from but chooses to make out it is a bunch of “young turks” that the wise old economists have rejected. All part of the denial process as him and his gang of journalists who enjoy a privileged position of being able to speak to the nation whenever they write are mounting to make themselves seem relevant.

He should retire after writing such nonsense.

best wishes

bill

I have read Gittins article (available here):

https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/the-real-reason-to-worry-about-mmt-is-not-the-theory-but-the-practice-20210228-p576fs.html

but was not able to comment because I don’t want to subscribe to the SMH.

Anyway I am not as dismayed by Gittins article as Allan and John are: Gittins actually seems to be on board with MMT, his chief concern being the “politicians inability to restrain themselves” meme.

eg Gittins writes:

“The monetarist dogma (following Friedman) that creating money inevitably leads to inflation turned out to be wrong. It’s inflationary only if it causes the demand for the “real resources” – land, labour and physical capital used to produce goods and services – to exceed the supply of real resources. Until you reach that point, the creation of more money – whether by the banking system or the government – should give you stronger demand and more jobs without causing problems.”

That is pure MMT, correct. Continuing:

Gittins: “So the real reason for worry about MMT isn’t the theory, but the practice. If you give a bunch of vote-buying politicians a licence to spend as much as they like up to a certain point, how could you be sure they’d stop, and revert to borrowing, when they reached that point?’

I wanted to write to the SMH: how about giving that power to the elected treasurer,subject to advice by treasury officials (non-elected public servants).

The Gittins article also hints at Lowe’s blurring of fiscal and monetary operations, to hide the truth of what is happening in the reserve bank. As for Garnaut, he is a free-market ideologue. I don’t see how the free market can sort out the matter of compensation for stranded fossil fuel assets.

Btw, guess where you CAN comment on articles, in the comments section of national media, without subscribing beforehand? That’s right: in “communist” China (eg the Peoples’ Daily)…. whereas SMH and ‘The Australian’ are behind paywalls. Go figure….

“I wanted to write to the SMH: how about giving that power to the elected treasurer”

How about putting in place a Job Guarantee – which eliminated *both* the clowns at the central bank and the clowns in the government (if that is you penchant).

Everything after that is essentially tax and spend.

You cannot have public sector jobs without the tax that will ensure they will stay in their jobs at the top of the business cycle. It is for Parliament to decide to impose that tax.

It’s fairly straightforward to introduce MMT ideas via full automatic stabilisers and require a balanced budget. You just won’t have enough public workers at the top of the cycle.

(There are advanced tricks you can do with lending and the like, but that required politicians who have attended at least three years of Bill’s lectures).

If you don’t trust the pilot let George fly the plane.

Arent a share of these profits going into superannuation and home equity of the middle class? Is there a way to assess if the middle classes share of profits is also decreasing relative to the upper class (upper class meaning the class which derives all its income from property)?

The real villain in the Ross Gittins SMH article is Philip Lowe himself, because – as Gittins noted:

“Ostensibly, the opponents of modern monetary theory (MMT) are led by Lowe, as boss of our central bank. At his appearance before a parliamentary committee last month, he replied to a question from Greens leader Adam Bandt that he would “push back” against any assertion the Reserve was “financing the government”. (Note the curious wording: not that it should, but that it already was.)”

Why would Lowe want to push back against the idea of “the Reserve financing the government”? Self-interest? Sheer bloody-mindedness? Protecting vested interests who benefit from the current arrangements? Or just delusional attachment to a failing economic ideology?

Dear Neil Halliday (at 2021/03/2 at 5:52 pm)

Why would Lowe push back?

Your final reason “attachment to a failing economic ideology”

best wishes

bill