Today (April 18, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Labour Force,…

The pandemic that just keeps giving, and not in a good way!

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. Today, he has taken a breather from teaching and exam marking to write about the long-run uneven labour market impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has been the global emergency that just keeps giving. And not in a good way! Daily figures from around the world show that the pandemic’s health impacts continue to be widely felt. So, it’s over to Scott to explain how.

Background

In Australia we have continued to see relatively large case numbers in our two most populous cities/states, although as vaccination rates rise above 90 per cent (first dose) and 80 per cent (second dose), these numbers are falling.

As I write this, the state of Victoria is still recording high numbers of daily cases, with New South Wales only just recently seeing a fall in stubbornly high numbers.

For Australia as a whole, while our number of cases is relatively small, the death rate measured as the number of deaths as a percentage of all non-active cases remains similar to other societies around the world.

From a health perspective we are not out of the woods yet.

There has been discussion about people suffering from “long COVID”, and there is presumably a whole lot of undiscovered long-term impacts.

Now, I am not an epidemiologist or a public health expert, so I can’t comment too much on these things.

However, it has been an interesting exercise observing the various power plays between the state and federal governments, the rise of some chief health officers to almost hero status and the posturing of big corporation bosses who firstly went cap-in-hand for government support and who have now had enough and insist that the economy must take precedence over all else and that the private sector must now be able to get back on course (all in the name of the greater good).

The long tail of COVID employment impacts

Despite the view that once the private sector starts firing again the economy will ‘roar back to life’, it is more likely that the negative labour market impacts of the pandemic will be with us for a while and furthermore that the impacts will be highly uneven.

Bill has already touched on the potential long-lived nature of the current unemployment crisis in his many posts reviewing the Australian labour market statistics.

See for example – Australian labour market continues to contract (October 14, 2021) – where we learn, among other things, that when we compare unemployment trends with previous economic downturns (the 1982 recession, the 1991 recession and the GFC) the labour market will take some time to bounce back once an unemployment peak is reached.

The truth is that when the recovery does get properly underway, gains will be patchy and there will be winners and losers. Some will move relatively easily back into employment, while other, often the most disadvantaged, will find it extremely difficult.

This point is well illustrated in the Report from Anglicare (October 2021) – Anglicare Australia’s Job availability snapshot 2021 – where the authors of the report point out that:

Most employment statistics assume that each person can compete for every job. We know this isn’t true … [and] … In spite all of the changes to the workforce over the past year, the number of people with barriers to work has barely budged. Even with a resurgence in the number of entry-level job vacancies, people with the greatest barriers to work aren’t getting them. They are competing with 27 jobseekers for each one of these roles.

Point 1: Any notion that the negative employment impacts of the COVID economic slowdown will be over once the economy ‘roars back to life’ are not accounting for reality and all reports that suggest otherwise should be considered with scepticism.

Uneven regional outcomes impacting on communities

Adding to the problems at an individual level is the uneven regional or spatial labour market context, which will mean that many people and the communities they live in will face ramped up long-term disadvantage.

In this blog post- Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash (February 11, 2021) – I wrote about the potential long-term ability of different regional economies to recover from the COVID induced economic slowdown arguing that we may well see several possible outcomes:

- regional economic rebound: a period or periods of decline followed by a movement back to a previous (pre-covid) path;

- negative regional economic hysteresis: a period or periods of decline followed by a lower than expected rebound

- positive regional economic hysteresis: a period or periods of decline followed by a higher than expected rebound.

There are of course many factors that will impact on a regional economy’s ability to rebound, including its pre-pandemic economic position, its industrial mix, the time and extent of public health imposed shutdowns and stay-at-home orders.

How different regions recover is important because as Bill and I have discussed in some of our academic papers including this peer-reviewed article in Geographical Research (July 2009) – People, Space and Place: a Multidimensional Analysis of Unemployment in Metropolitan Labour Markets – regardless of your individual characteristics (level of education, family background etc), the type of regional labour market you live in has a significant impact on your employment opportunities.

Put simply, the fact that different regions will recover at different speeds will mean that out-of-work individuals in poorly performing regions will be significantly disadvantaged in attempting to re-engage with the paid workforce.

That seems like a no brainer, but is often overlooked when policy is being considered and when politicians talk about how robust the Australian labour market is.

As a side note, understanding these regional impacts and the patterns that have emerged in terms of regional economic decline and recovery is something that Bill and I will hopefully be doing some concentrated research on in the new year, provided our research grant application is funded.

Point 2. We are highly likely to see significant regional variation in employment impacts resulting in concentrated pain and suffering as communities struggle to move forward. Moreover, it is very likely that the most disadvantaged regions and communities will be the ones that are hit hardest.

COVID impacts on family employment outcomes and beyond

Another way the pandemic will just keep on giving is in terms of the intergenerational labour market impacts.

Social scientists have been discussing intergenerational transfers of poverty and disadvantage for some time.

This report from the University of Melbourne (October 2020) – Does poverty in childhood beget poverty in adulthood in Australia? – provides a useful reference point regarding the issue of poverty and we can extend the arguments to think about labour market issues.

In a number of acaademic papers, Bill and I have identified an association between the risk of being disadvantaged in the labour market and parental employment history. In the Geographical Research article, I referred to earlier, we also identified that individuals were significantly more likely to be disadvantaged in the labour market (face unemployment) if their parents had not been in the paid workforce when they were children. This impact was taking into account all of their other characteristics (that is, level of education, age, sex, ethnic status etc).

So, for a child, living in a jobless family is clearly not good and in the case of the current employment crisis, it is likely that the negative employment implications for certain groups will long lasting.

To get an idea of the potential size of the problem, we can look at the Australian Bureau of Statistics labour force estimates of families which are produced from data collected in the monthly labour force survey (LFS).

The labour force survey is the same data source that Bill uses for his discussions about the monthly unemployment and labour force outcomes, and so the usual caveats that he warns about apply to the family labour force data.

For context, a family is defined as two related people who live in the same household. This includes all families such as couples with and without children, including same-sex couples, couples with dependants, single mothers or fathers with children, and siblings living together. At least one person in the family has to be 15 years or over.

Considering the latest release of the dataset – Labour Force Status of Families (released on 12th October 2021, but referencing June 2021) we see that:

In June 2021, there were 93,500 jobless couple families with dependants (including children under 15 and dependant students aged 15-24 years), down from 133,000 in June 2020. 80,000 (85.4%) of these families had children under 15. An estimated 162,000 children aged 0-14 years were in jobless couple families …

There were 190,000 jobless one parent families with dependants in June 2021, about one third (29.1%) of all one parent families with dependants. 90.2% of these jobless one parent families had children under 15. This equated to an estimated 315,000 children aged 0-14 years in these families.

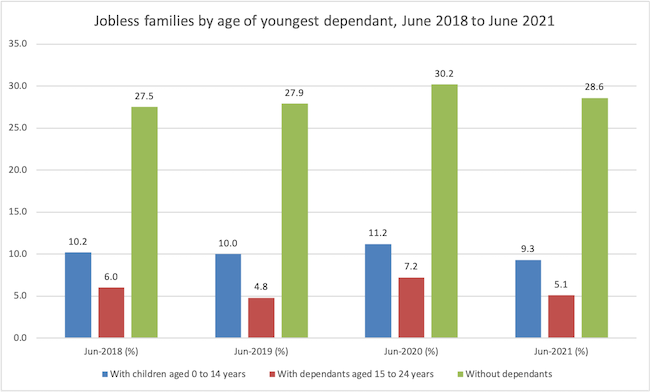

We can see from the following graph (Source) that even in earlier years (2018) the numbers of children living in jobless families (especially those aged 0-14 years old) is significant, illustrating that the problems associated with jobless families are not just a COVID phenomenon.

Like a range of other social problems, the health crisis and the accompanying economic hit has made these issues for more visible.

Those living in jobless families are likely to be facing extreme financial pressures and poverty which in turn has been shown to impact on education attainment and a host of other negative social outcomes.

This is a double whammy leading to further disadvantage when young people move attempt to move into the labour market- poor education attainment coupled with a lack of exposure to employment role models.

In some of the research I have been reading the impact of parental joblessness on the future outcomes for young people have pointed to the dual impacts of poor education attainment and parental joblessness.

In the Australian context, you can read some recent findings in this report – Pathways of Disadvantage: Unpacking the Intergenerational Correlation in Welfare (January 10, 2020) – where the authors point out that:

intergenerational persistence in economic disadvantage can largely be understood through an education lens. The single most important mechanism linking welfare across generations is the failure to complete high school … [and] …

Disadvantage is also being perpetuated from one generation to the next through the parenting that young people receive. The issue is not the style that parents adopt (i.e., warmth and monitoring), but rather the relative lack of support – particularly financial support – that welfare-reliant parents provide. Without adequate parental support, young people’s ability to successfully transition from education to employment may be constrained.

This Report from the TNational Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE) – The impact of ‘learning at home’ on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic (published April 2020) – shows that the problem is also perpetuated by the transition to home schooling during the pandemic, which may have impacted on children in disadvantaged families (those most at risk of seeing some form of negative intergenerational impacts) who may struggle to catch-up with their educational levels.

So, if this intergenerational transfer of disadvantage persists into impacting on young people’s successful transition into the workforce, then it is not too much of a stretch to see the potential that the current pandemic related employment problems will have going forward.

Point 3: We are likely to see significant intergenerational issues flowing into the nature of labour market disadvantage in years to come.

Conclusion

There continues to be much rhetoric around Australia ‘bouncing back’ and the country ‘living with COVID’.

Part of the rationale seems to be the thought that once the economy ‘roars’ back to life, the unemployment crisis that has been exacerbated by the pandemic will be over and we can all get back to doing what we were doing prior to the pandemic hitting. This includes the government returning to their pre-pandemic mode fretting about budget deficits and spending and punishing the most vulnerable in the process.

As an example, the federal government will not be doing any favours to disadvantaged individuals, communities and families as they wind-back the support measures introduced at various times during the past 18 months or so.

Anyone with a basic grasp of the facts would question the wisdom of the government’s action. Despite what we are told we are not out of the COVID-19 woods just yet.

There will be a long tail of labour market disadvantage that will unevenly hit individuals, communities and families.

There remains (just as there was pre-pandemic) a need for a transition in policy thinking and action which ensure that everyone benefits and as few as possible fall through the cracks.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks Scott and Bill, keep up the good work, cheers, John

“There continues to be much rhetoric around Australia ‘bouncing back’ and the country ‘living with COVID’.” As there is around much of the rest of the world. No one at this point can know the ultimate outcome of the pandemic, but perhaps the worst outcome would be a bounce-back into a predatory, ecocidal global economy. Among those who work in hospitals, it’s called getting better to die.

Thank you Scott for the nice and enjoyable to read prose. The article is written with relevant and supporting evidences especially when arguments were put forward.

There are many important take-aways on offered – longer effect of the pandemic, especially on certain population cohorts, hence, well designed and more specific fiscal allocations should be crafted to avoid the foreseeable but avoidable suffering.

I hope you and Bill will receive the much deserve funding for any research plan you might have in the next year.

Here, I would like to suggest a few things: could the research funding be in the form quasi experiment? Meaning, propose the “conceptual policy” with the right kind of budget needed, to carry out a study comparing two similar cities, one with the kind of the fiscal intervention you have in mind, and the other just the usual government support – to see how these two will turn out, say – after a year time, using standard and relevant measures as key indicators.

If there is an improvement, this kind of proposed policy and further intervention could be duplicated in other similar cities a few more studies.

Along the way, the MMT’s concepts and proxy measures could be captured and documented in the final report as well, Such as the impact of the fiscal expansion on the local economy before and after, and in comparison. This would provide additional MMT literature a great deal among the other developing fronts we may have.

This paper is good, useful and forward looking. I agree with the analysis and conclusions. I also think it is important to remember the history of COVID-19 and “maintain the rage” against neoliberal capitalism. This pandemic never should have been unleashed in the first place. It was containable, suppressible and eradicable, especially before it mutated. I mean both originally and then when it hit Australia (with multiple incursions). A whole raft of bad, neoliberal capitalist policies contributed to permitting the global pandemic to spread out of control. Indeed the policies were (and are) so bad they amount to the deliberate sabotage and sacrifice of people, society, and the economy.

I mean “sabotage” in the standard sense but also in the implied Veblenian sense, so-called Veblenian sabotage (meaning Veblen identified it, he did not create it). I will leave people to research Veblen and “Veblenian sabotage” themselves. Suffice it to say here that MMT (and genuine and original Keynesian-ism I would argue) propose that the modern money system should be used to help all the people rather than be used as the neoliberal system uses it to sabotage the true possibilities of the economy for all people in favor of outrageous and un-taxed profit for a tiny, exploitative minority.

Since I am slightly off the explicit topic I will leave it there. But while arguing against and working against the ensuing damage of neoliberal policy we must never forget how each manifestation of original sabotage of better possibilities leaves a huge tail of destruction and huge mess for the real workers and the real thinkers to try to clean up. In the end, prevention is better than cure, both medically and economically. The power of the rich and powerful to enact and carry out Veblenian sabotage policies has to be pruned and then rooted out entirely.