The IMF and the World Bank are in Washington this week for their 6 monthly…

We are not going back to the 1970s

With Russia now invading Ukraine and adding to the already highly disrupted supply chains linking products and nations, and the price fixers in OPEC and OPEC+ having a picnic on the uncertainty, inflationary pressures will continue to rise for the time being. Many commentators keep falling into the trap of saying that history is repeating itself – meaning that it is the 1970s over again. I maintain my position that this is not akin to what was going on in the 1970s although there are similarities – energy price rises accompanying war, etc. And if we make the same mistakes that were made in the 1970s now, then not only will the inflation persist but millions of workers will lose their jobs and their incomes.

The changing role of unions in society – the worldwide decline in trade union membership

One of the striking aspects of the current period is that the prices of goods and services are rising as supply shortages become binding in an environment where Covid stimulus support has helped maintain purchasing power.

Normally during a pandemic (historically) demand drops sharply, but this time around, that has not occured across the board, although services spending declined while spending on goods rose.

Those sectoral differences were created by lockdowns and other restrictions, illness and shifting patterns of preference.

They are unlikely to persist although elements will – such as, more on-line shopping.

But the other stark fact is that one service has not been able to secure price rises – labour.

Despite labour shortages emerging due to sickness and border closures, wages growth remains at low levels and that appears to be a global trend (with some sectoral exception in some nations).

In part, this problem has arisen because unions are in decline in many countries.

Various factors are driving this decline including legislative attacks from governments over the last four decades; the changing composition of the workforce (away from big manufacturing plants which are easier to organise towards small service workplaces, which are hard to organise; increased casualisation; increased participation of women; increased use of short-term migrant labour to undercut wages; and more.

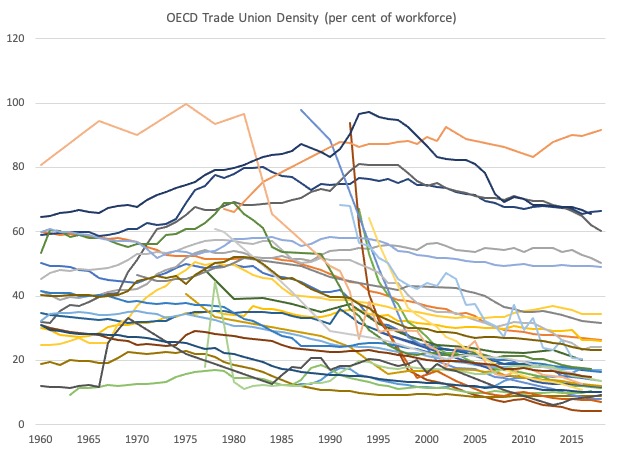

The decline in trade union density (proportion of workers in unions) is a global phenomenon.

The following rather messy graph uses the OECD trade union density data from 1960 to 2018 for some 35 nations (only Israel is missing) and just demonstrates the historical decline.

That is Iceland at the top resisting the trend (especially since the GFC collapse of the banking sector).

Here is a less messy graph showing some of the big declines since the 1960s.

There is some evidence that the COVID-19 crisis is now encouraging workers to once again join unions but it is too early to tell whether this is a trend or not.

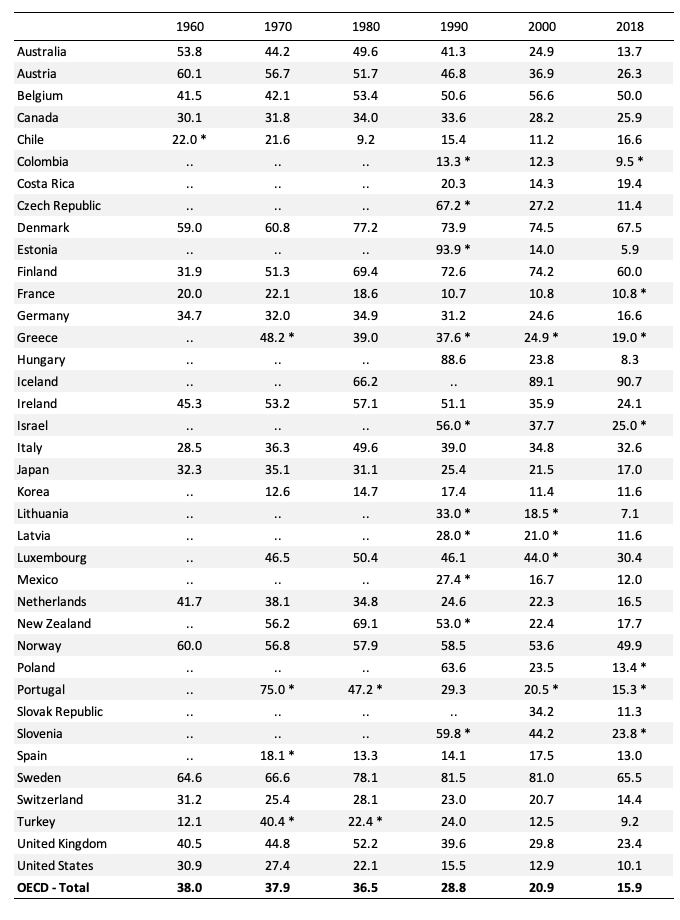

The following Table shows the decline in union membership in numbers. The * indicate decades where data is not completely available.

So in density terms, we are not remotely facing union strength like in the 1970s.

What about industrial disputation?

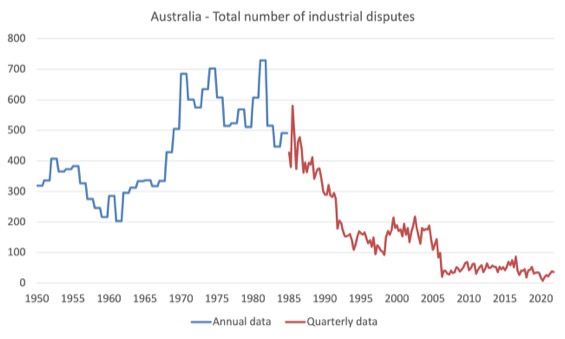

I have data on industrial stoppages back to 1950 and it provides an historical context for understanding the current data trends.

Last week (March 10, 2022), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest data – Industrial Disputes, Australia – for the December-quarter 2021.

The numbers are very low and I thought it would be interesting to provide some historical context in order to discourage conclusions that we are just back in the 1970s again.

While this post is about Australian data, the trends discussed apply to most nations, where different forces have combined to make it difficult for workers to gain wage increases.

The following graph shows the industrial stoppages (number) from 1950 to the December-quarter 2021.

Up until 1985, the data is only annual and then the graph uses the latest quarterly data from the ABS. I assumed the annual aggregate before 1985 was distributed evenly through the 4 quarters of each year, which is why it has that funny Lego block look.

But just focus on the levels over time, they tell the story.

Industrial disputation was much more frequent before the legislative attacks on the unions began in the 1980s.

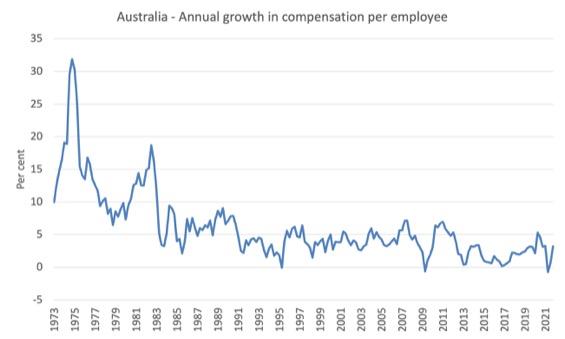

To see why this matters, here is a graph showing the annual growth in compensation per employee since the March-quarter 1973 in Australia to the December-quarter 2021.

This is one measure of wages growth – but the current data based on the Wage Price Index only goes back to 1997.

Think about the disputes data when thinking about the wages growth data.

With the decline in union power as membership waned and the introduction of a range of pernicious legislative contrivances which made it hard for existing unions to pursue industrial action in pursuit of wage rises, the rate of growth in wages has slumped and stagnated.

Wages are growing at record low levels now.

Further, they lag behind CPI rises rather than lead them, which means there is a fundamentally different dynamic operating.

So there is really no comparison with what went on in the 1970s in terms of the capacity of workers to enjoy wages growth and the situation at present.

Should petrol excises be cut or scrapped to deal with inflation?

I have often pointed out that a significant factor driving price level pressures, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, are institutional and administration arrangements imposed by government.

Things like indexation arrangements – for example, allowing private health funds to automatically increase premiums each year in excess of the CPI.

Other drivers include excise taxes.

In Australia, the federal government imposes an excise tax on fuel and petroleum products and the rates are indexed twice a year to movements in the CPI.

The current conservative government made that process automatic from July 2015.

As at February 2022, the rate is 44.2 cents per litre and for LPG it is 14.5 cents per litre (Source).

The government levies the tax to raise revenue and in 2019-20, the data shows the government took $A5.6 billion out of the pockets of consumers through excises on petrol and a further $A11.8 billion from diesel (although diesel rebates gave a lot of that back.

The Australian Automobile Association claims the total net revenue from excises is around $A11 billion annually (Source).

In recent days, with the price of petrol now escalating, there have been calls for the federal government to cut the excise to take pressure of the price.

This ABC news article (March 14, 2022) – Federal government faces calls from within to cut fuel excise as petrol prices soar during Ukraine war – provides some information.

The usual suspects have assembled on both sides of the debate.

It is true that if the federal government did cut the excise and were able to control the greed of local distributors (presumably through a legislative fiat forcing them to cut the price – did I just say ‘price controls’) then workers would suffer less real income loss as a result of their use of motor vehicles.

Economists have come out with some ridiculous statements about the proposal.

The kooky-one who professes expertise on anything that moves basically tweeted (March 13, 2022):

If the petrol excise is reduced, the budget shortfall that causes will have to be borrowed, adding to govt debt.

That debt will require higher taxes to pay the interest on it & then in time to repay it.

Ridiculous policy – highlights how shallow the economic debate is right now

It is hard to know what to do with an economist who thinks like this.

First, the revenue surrendered does not ‘have’ to lead to higher debt if the government chooses otherwise.

Second, the term ‘higher taxes’ is ambiguous.

Does he mean higher tax rates, meaning at each GDP level, tax revenue would be higher?

Or, does he mean that tax revenue would be higher with the same tax rates?

In the first case, I have never seen any robust relationship between changes in tax rates and the dynamics of the fiscal balance. I have observed periods where the fiscal balance has increased while tax rates have been cut and vice versa.

In the second case, as economic activity rises, tax revenue increases automatically with no discretionary policy change because, for example, more workers are employed and paying tax.

Does he then oppose those increases in tax revenue?

Further, history tells us that debt is repaid not through higher tax revenue specifically but by issuing new debt (given the institutional arrangements that our governments hang on to).

Finally, public debt is non-government wealth. So even if his logic (the causality) is correct, that means he is seemingly opposed to a rise in non-government wealth being the result of a rise in real purchasing for citizens who purchase petrol.

Anyway, Kooky, as I said.

Another character, who seems to be the darling of the ABC (they always wheel him out) claimed:

You can’t solve a problem caused by President Putin in Europe with tax relief in Australia …

Yes you can.

Cutting the excise would clearly benefit the real income of motor vehicle users.

What that economist did get right is that the price of oil is already starting to come off anyway and it doesn’t make sense to set tax rates to some fluctuating numeraire.

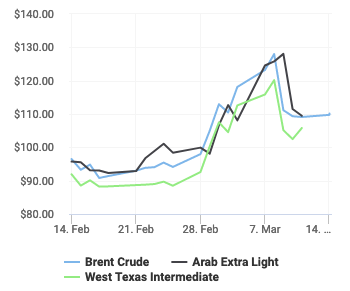

Here are three representative oil price movements since February 14 to March 14, 2022

Overall, my position issue is this.

We actually want people to drive less not more given the environmental emergency.

The more people stop driving and ride cycles instead, or walk, or pool cars, or, spare the thought take public transport, the better.

Those options are not always possible but where they are they are preferred to everyone getting into their own cars each morning and clogging up the roads and the air quality.

So I am reluctant to support a measure that provides an incentive for more motor vehicle usage.

I also note a curious inconsistency between green types who are coming out to support the proposal – presumably on equity grounds – yet at the same time argue vehemently for carbon taxes and the like.

My only concern about advocating more public transport at present relates to Covid, which has made such conveyances less safe than the private car.

Conclusion

There is a lot of knee jerk doomsayers out there at the moment.

First, there is really no comparison with what went on in the 1970s in terms of the capacity of workers to enjoy wages growth and the situation at present.

Second, a nation should not adjust longer term fiscal parameters to deal with a short-term crisis.

Third, the inflationary pressures remain transitory in my view.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I believe it was the Australian Financial Review who recently released modelling purporting to show that wages in Australia can be expected to rise by at least 8% this year.

It’s a fantasy that ignores the basic reality that the average worker is simply not on equal footing with the capitalist and has limited capacity to bargain for a better deal without the backing of strong unions – which are largely absent today. Add to this the federal governments goal of flooding another 200 000 or so guest workers into the labour market by the end of the year and the notion of a powerful wage breakout occurring any time soon appears nonsensical.

At least Phil Lowe appears to be continuing to resist pressure to hike interest rates to forestall a supposedly inevitable wage-price spiral and keeps re-iterating that he wants to see actual evidence that wages are in fact growing solidly before he’ll consider going on a rate hike binge.

“At least Phil Lowe appears to be continuing to resist pressure to hike interest rates”

I know this feels weird but the RBA continues to be a voice of reason, if only when it comes to a rise in interest rates.

New Zealand has announced both a reduction on fuel excise and halving of public transport fares. Some cannot avoid driving. Ideally though public transport should be free. Working from home helps too.

I think a rise of 8 per cent is not out of the realm of possibility but to me it just suggests employees are playing catch up with the past two years in which wages have likely seen no movement at all. Wage rises I think are even more transistory.

Anecdotally, many of the great resignations from people I’ve known have been due to an attempt to increase their wages after the sacrifices of the past two years only to be denied by their employers. So they have switched careers to ones that at least provide better work life balance. It’ll be interesting to see how we shift culturally on our views on work.

History is repeating itself, but not in the sense of 1970.

More in the sense of 1941.

Now as a farce, just like Marx predicted.

There is no industry with strong unions to put pressure on wages, so goodbye 1970.

There are huge number of powerless workers with precarious jobs, too afraid of loosing the meagre income they have.

Just ask a gig worker about that.

Hello 2022.

Nevertheless, there is a possibility of wage pressure in europe in the near future.

Europe is largely dependent of immigrants to keep unployment high and wages low, but what if europe becomes too risky to live in?

What if immigrants find their home wars less risky than europe’s war?

Hedge-funds have found a way around this, just like the way they found in 2008, to amass an even larger portion of the world’s wealth.

They are buying the assets of companies leaving Russia in a hurry.

Hello again 2022.

Anyway, there is a pressure indeed, but not on wages: pressure on nato, to intervene in the war in Ukraine.

People are affraid of beeing stigmatized, only for saying something not blatantly anti-Russian.

You can measure this by the way we now accept as very civilized the outrageous practice of using civilians as human shields.

So, maybe WW3 is on the making, and some say it is on the making since 2014.

Maybe nato is waiting for a motive to intervene.

They are selling guns to Ukraine and storing them near the Polish border, so any misfired shot or even a red herring might just give them the motive they been waiting for.

Or even the use of chemical/biological weapons – so dear to the US – just might be what will trigger WW3.

Anyway, we already know that Russia is going to be the one responsible for the war.

You could ask: what about nukes?

Doesn’t that frightens everybody?

Well, I don’t have an answer to that.

The elites might think the US is capable of neutralizing Putin’s nukes on the ground or after they been shot, in the air.

Maybe they plan to kill as many Russian as possible, to take hold of the colossal wealth Ieltsin showed them and Putin took away.

Anyway, we are all expensable and only the 1% need to be alive in the aftermath of WW3.

I imagine there are many bunkers around…

Either way, when all is said and done there is a real risk that MMT is going to get blamed for the inflation.

How are they going to do it ?

Everybody has just had a ring side seat to the show. First with the pandemic then with the war. How framing and narratives are both created and controlled. Anybody who questions both are cancelled.

The right and centre right voters will agree as they can’t get passed ” Government spending = inflation and shrink the state”

The left voters think MMT is nothing new and can’t win an election.

A month ago it quite easy to believe if the general populace was better educated in these matters – that is, understood the actual operational capabilities of the national government it would be very difficult for the politicians to conflate their own ideological desires with the concept of a financial constraint.

They would know that governments could afford to fully employ the available workforce as long as their were sufficient real resources available to provide the extra food and other things the higher employment levels would invoke. This would then require a higher level of sophistication in the public debate.

Businesses would also have to justify their opposition to true full employment in more sophisticated ways because the voters would all know that the usual reasons they give – again relating to government budget constraints – are all deeply flawed.

Today, you could very easily say the debate does not matter and will be completely ignored. We have a one-party parliament, a one-party media. Contrary voices are being systematically eliminated, one by one, by a one-party big-tech army of auxiliaries.

Today it has just got a lot harder for MMT’rs the world has changed. The risk has always been there but for me it has just got amplified. Let’s see how it plays out and hopefully they have overplayed their hand.

Now there is a serious debate to be had and there was always a debate to be had, that if every country on the planet understood MMT. Would they be allowed to implement their own economic policies using the MMT lens?

Yanukovych knows the truthful answer to that question. So do the South Americans and EU states and large parts of Africa.

Not only will the IMF and World bank and EU not allow it. NATO has already made it quite clear what economic policies have to be in place in order to get NATO protection.

https://forbes.ge/the-economic-effect-of-nato/

A complete fairy tale of neoliberal, globalist nonsense.

The reality being that the country is put into debt and then severe austerity imposed on the country. The public sector is transformed into a rent extracting monopoly. Pensions are slashed and free trade policies are introduced and laws are changed to allow investors to privatise the profits and socialise the loses. Who then threaten investment strikes to hold a faux/ puppet government to ransom. The real resources are sold off to the highest bidder. All the rest of it that was a explained quite clearly in reclaim the state and European Dystopia.

So for me, no they don’t have a choice. Even if they understood MMT they don’t have a choice. As the ring side seat over the last month has shown quite clearly what happens if you even think about it. Don’t follow the crowd.

” You are either with us or against us “

John O’Sullivan the architect of Thatcherism who pushed all her economic policies through. Told everybody in the 90’s that the neoliberal and globalist view point was going to be part of NATO expansion economic policy. That everything was going to be linked.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=BZMVKwmeprY

If they don’t get you via NATO ‘s expansion . They get you via EU expansion. If you refuse to join either to try and remain an independent nation state and decide your own trade policies. Then you are quickly put in the ” against us ” catergory. Think tanks and media will be put in place to sculpture the minds of voters to think in the right way. Elections and referendums will be held until you vote in the right way.

Against your own interests and turned into a rent extracting monopoly. Depoliticised with your democracy turned into a 3 card monte con trick.

“Today it has just got a lot harder for MMT’rs the world has changed.”

What we have is a mainstream that jumps on semi-inflation as soon as it starts to happen, ie any price changes at all, and demands interest rates rise to stop it.

That means they get their retaliation in first. People don’t like price rises, even though at this point it is just the market allocating scarce resources. Therefore they get a hearing for their nonsense.

So perhaps what we need to do is accept that semi-inflation is politically unacceptable and instead counter the demand.

Interest rate rises are a way of reducing the amount of money workers have to spend by putting their mortgages and rental costs up. And that works by taking money out of the pocket of workers and giving it to those nice rich people with money as interest payments on their savings. The rich get richer because they don’t spend, and those with mortgages to pay and houses to heat lose out.

How about instead we increase taxes on workers, but make the businesses that employ them pay that tax. That way we still reduce the amount of money that is spent, but on the business side this time, and no rich people get a windfall. Much fairer, far more equitable.

If the semi-inflation crew want to start hooting and hollering, then let’s point out a process by which they pay as well. Then let them try and explain the dynamics rather than us.

The Biden administration in the US is making commitments in the hundreds of billions to long overdue public infrastructure rebuilding. One can only hope some forward planning for sustainability is being worked in to this as well, but this is something that has the potential to cure the current economic and political malaise which has befallen that nation, and could well be a good prescription for many others.

The two worst corporate Democrats Joe Manchin and Kyrston Sinema have effectively killed Biden’s and Bernie’s Build Back Better program. Manchin is Congress’s biggest recipient of oil industry bribes/donations so the Green New Deal components along with most social welfare components have been dropped and the remaining infrastructure components trimmed so as to be ‘paid for’ by funding cuts to other programs or some tax increases.

Neoliberalism still rules in the US and the decline of the US will continue especially if as expected the Republicans regain control of either the House or the Senate following the 2022 mid term elections.

@Euginio Triana

Hi Euginio – are you in Australia?

I’m not sure what mechanisms exist here that could allow for a near-quadrupling of the average workers wage increase. No doubt those in the upper part of the labour market will (as is typical) have greater success in this regard. But I can’t see the average worker doing remotely that well.

The institutions that allowed for such increases broadly across the labour force are gone – unions are the palest shadow of their former selves, industry wide bargaining is gone etc. The almost complete loss of industrial power by workers in this country since the 70’s would seem enough to me to make it very difficult for the average worker to ask for better, unless perhaps unemployment/underemployment were running down near frictional.

But I’m not convinced we’re going to get that low – now that Covid appears to be receding and borders re-opening, government is chomping at the bit to resume the pre-pandemic policy of flooding the Australian labour market with foreign labour to compete with local workers.

So I think wage increases for the average Australian worker face a two-pronged stumbling block – the absence of unions and industrial power to force employers to the bargaining table on one hand and on the other, the diluting of any power workers might have otherwise had by the resumption of the policy of allowing employers to choose from an imported smorgasbord of labour, giving them the option to avoid employing local workers.

The notion of 8% wage increases suddenly becoming typical is I think based on the presumption that the labour market still functions exactly as it did in the 70’s (when my own father was a rather militant trade unionist) – I’d say it’s an entirely different beast today.

And not one in favour of workers.

I like the way Neil Wilson looks at the problem and I think his solution is more equitable than most. On the other hand, if there is just less gas and oil available to purchase because of this war (and our policy reactions to it), it seems to me we have to suffer getting along with less of those real resources- whatever tax structures are changed. So it is a hit to our standard of living no matter what.

The bright side is that theoretically, we would use less of these products at the higher prices. And have more incentive to use alternatives. And that may be best for the environment.

The other real resource that there may be less of is food. Russia and Ukraine are both large exporters of grains. I know little about farming, but I imagine when your country is getting invaded, it may be difficult to grow crops. And shortages of food are especially hurtful to the poorest throughout the world.