It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

The Eurozone fictions continue to propagate

There was a Financial Times article recently (January 8, 2023) – Monetary independence is overrated, and the euro is riding high – from Martin Sandbu which strained credibility and continues the long tradition of pro-Euro economists attempting to defend the indefensible – fixed exchange rate, common currency regimes. He claims that the Euro is a better system in the modern era for dealing with calamity than currency independence. However, as I explain below, none of his arguments provide the case for the superiority of the Eurozone against currency-issuing independence. Currency-issuing government can certainly introduce poor policy – often because the policy makers refuse to acknowledge their own capacity and think they have to act as if the nation doesn’t have its own currency. But the negative consequences that flow from testify to the poor quality of the polity rather than any disadvantages of the currency independence. The Euro Member States are being bailed out by the central bank and if that stopped the system would demonstrate the inherent dysfunction of its monetary architecture and nations would fail.

Sanbu’s argument is as follows:

1. European nations are queing to join or use the euro as their currency – thereby surrendering their own currency sovereignty.

2. That means the common currency is attractive.

3. Arguments that the surrendering one’s currency sovereignty is dangerous and ultimately costly “are becoming increasingly unpersuasive, while changes under way in how money works speak to the euro’s advantage.”

4. Having one’s own currency is now a liability. He constructs this argument by claiming that the advantages touted by those who support currency

“independence” think the advantage is that when the currency depreciates, exports rise, which offsets any costs from depreciation.

He cites the example of Britain, which he claims has experienced a depreciation without any commensurate export increase and the rising import prices has made the people poorer.

In fact, since the GFC, the pound has strengthened against the euro. One pound bought 1.1327 euros in January 2010 and by the end of 2022 it bought 1.1512 euros.

Further, it is difficult to make assessments about Brexit because of the uncertainty in the data introduced by the pandemic.

What the GDP per capita data tells us is that prior to the pandemic Britain was in a much stronger position that the 19 Member States of the Eurozone and is now only slightly worse than the Eurozone nations.

The UK suffered more during the pandemic than the Euro nations but only marginally.

The difference is outcomes is hardly testament against monetary sovereignty or Brexit or the range of factors that Euro apologists cite

Further, I would not construct the case for monetary sovereignty on the export capacity of a nation.

The EMU was designed to harness disparate forces (historical, cultural, language, etc) in Europe into a common monetary framework via the imposition of rather strict rules relating to fiscal policy (SGP) and monetary policy (no bailouts).

When those rules are applied the differences between individual nations in economic capacity become obvious rather quickly and in 2010 and 2012 we saw how these differences coming up against the rules drove nations such as Greece and Italy to near bankruptcy.

Currency-issuing nations did not come under the same sort of bond market pressure as the individual Member States using the euro did during the GFC.

If the ECB had not effectively funded the deficits of these nations – in violation in my view of the treaty rules – then those nations would no longer be using the euro.

No currency-issuing government faced bankruptcy realties during the GFC or since.

That is the way in which to think about the advantages of currency sovereignty or independence.

Australian governments never face credit risk in running deficits.

Italy always does and relies on the ECB to reduce that risk.

5. Sandbu claims that the superiority of the common currency has been “highlighted by Europe’s energy price crisis”

He writes:

Take Slovakia. Yes, it has to contend with similarly high inflation to its non-euro neighbours. But it does so while enjoying a much lower interest rate (the European Central Bank’s 2.5 per cent) than the Czech Republic and Poland, where borrowing costs are nearly three times higher, or Hungary’s 13 per cent.

The facts are the facts.

But they don’t provide a case for or against a common currency.

They tell us that:

(a) The central banks of the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary have hiked their own interest rates higher than the ECB in the misguided belief that the higher rates will somehow address a massive supply side shock, which is driving the inflation episode.

(b) That indicates the mainstream ideology is at work irrespective of the currency status.

(c) Further, the governments of the non-Euro nations mentioned above are only enduring ‘higher borrowing costs’ through choice. Their central banks could simply do what the Bank of Japan is doing and control yields in their bond markets or better still they could just stop issuing debt to match the government spending.

Again, this is a statement of ideology not the intrinsic capacity of the currency.

(d) Slovenia has lower ‘borrowing costs’ because the ECB is controlling spreads.

If they didn’t, then because the Slovenian government is totally dependent on private bond markets to provide euros to allow fiscal deficits to be recorded, that nation would quickly see bond yields rise, irrespective of the policy interest rate set by the ECB for the overnight cash rate.

6. Sandbu writes:

Size matters in a global economy whose rhythm is still set by the US financial cycle, and it is only the monetary unity of the euro economies that affords the ECB a degree of independence from the US Federal Reserve.

Tell that to Japan.

It is running a monetary policy quite at odds with what the US Federal Reserve is doing and can sustain that for as long as it likes.

7. Once again, Sanbu uses Britain:

Last summer, however, it was not Italy, but the UK’s new populist government that badly rattled markets with irresponsible policymaking. Eventually, the Bank of England had to intervene to contain sovereign yields.

Again, what happened in Britain was not the result of having its own currency but rather the fact that its government was riven with division and the uncertain of its policy choices – flip-flopping.

The bond markets knew that these factors would allow them to challenge the currency (short-selling etc) and the government would fold and deliver profits.

The pension funds were also poorly managed due to the neoliberal dynamics that saw CEO salaries increase ridiculously which provided a source of financial weakness.

I covered that issue in this blog post – The last week in Britain demonstrates key MMT propositions (September 29, 2022).

I also continue to ask this question: If Britain demonstrated the power of the bond speculators then why hasn’t Japan fallen to the same outcome given the amount of posers lining up each day to ‘test’ the yen?

8. Apparently, the ECB is better placed to introduce digital currencies – although no evidence is provided for that assertion and the advantages are less than clear.

Remember how crypto was going to replace central banks?

But …

On January 1, 2023, Croatia finally walked the plank and joined the Eurozone, 10 years after accessing membership to the European Union.

Pro-European types used it to argue that far from in decline the Eurozone is the way forward and as the sub-heading of the FT article posits:

Old misgivings about the currency are increasingly unpersuasive – it is becoming more attractive by the day

Two things should be borne in mind when assessing the veracity of this statement:

1. Since the pandemic, the pernicious rules defining the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which make it almost impossible for the (now) 20 nations using the euro to enjoy sustained prosperity – have been relaxed under emergency provisions (the general escape clause).

In the – Council Recommendation of 5 April 2022 on the economic policy of the euro area, OJ C 153, 7.4.2022 – which is the most recent statement from the European Commission on the subject, we learn that:

While the general escape clause will remain active in 2022, it is expected to be deactivated as of 2023. With the economic recovery taking hold, fiscal policy is pivoting from temporary emergency measures to targeted recovery support measures. The increase in government debt ratios from 85,5 % of GDP in 2019 to 100 % of GDP in 2021 has reflected the combined effects of the contraction in output and the necessary policy reaction to the very large COVID-19 shock.

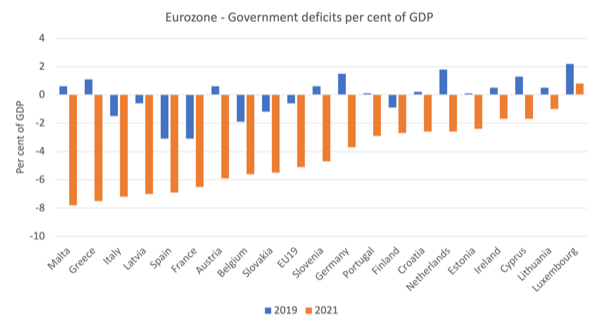

The following graph shows the fiscal position for the current 20 Member States in 2019 and 2021 (the red horizontal line is the 3 per cent SGP threshold).

While before the pandemic only Spain exceeded the permitted SGP fiscal deficit threshold, by 2021 the major of nations were above it and would, if the Excessive Procedure was enforced – as the above Council Recommendation hints will be the case in 2023 – be subjected to fiscal austerity dictates from the European Commission, which would blunt any growth progress they might have made.

2. The ECB now holds more than 25 per cent of all debt issued by Eurozone governments (see the following graph) as a result of a myriad of government bond-buying programs that began in May 2010 with the Securities Markets Program (SMP) and continue into the present – in multiple forms (APP, PEPP etc).

Taken together, the original design of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) has been ignored by authorities when faced when a major collapse (first, during the GFC, and, then, second, as a result of the pandemic).

The reason the Eurozone remains intact is not because the original architecture was sound and capable of withstanding external shocks.

Rather, it is because the central bank has deliberately ignored the so-called no-bailout clauses in the relevant treaty and has been keeping the private bond markets at bay by funding government deficits (indirectly) and suppressing yield spreads.

Then the European Commission went a step further and suspended the application of the – Excessive Deficit Procedure – its so-called “corrective arm”

So the fact that the GFC dynamics – where many nations faced bankrutpcy – have not been repeated during the pandemic – is because the EMU architecture has been put to one side and the main economic institutions have been operating ‘outside’ the normal system.

If the Excessive Deficit Procedure is reinstated, then the only way some of the Member States will avoid bankruptcy is through continued ECB bond-buying.

If that was abandoned, then we would rather quickly see a regress to calamity.

Conclusion

None of his arguments provide the case for the superiority of the Eurozone against currency-issuing independence.

Currency-issuing government can certainly introduce poor policy – often because the policy makers refuse to acknowledge their own capacity and think they have to act as if the nation doesn’t have its own currency.

But the negative consequences that flow from testify to the poor quality of the polity rather than any disadvantages of the currency independence.

The Euro Member States are being bailed out by the central bank and if that stopped the system would demonstrate the inherent dysfunction of its monetary architecture and nations would fail.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Excellent Bill,

3. There is a war between different economic ideologies taking place in Europe.

Sandbu ignores the geopolitical landscape but scratch the surface and you can hear him say it under his breath. He also talks as if the actual voters want to be in the Eurozone which is quite frankly absurd. Ignores two simple facts.

1. The handpicked face put in front of the electorate that represents the ruling class decide the outcome not the voting public.

2. The voting public have been brainwashed over many years by an economic theory that is false. All the framing and narratives they have heard since they day they were born are lies. Making the democratic choices they are faced with nothing but a sham.

If Sandbu was honest, he would replace the word countries with the words the ruling class and corporate interests. As it is they, who want to join the Eurozone and the US rules based order for their own selfish reasons. They couldn’t give a damn about the voters in each country that they are supposed to represent.

Sandbu framing and narratives are the everyday norm. He deftly danced around the geopolitics and hides the truth, because his income and reputation depends on him doing exactly that. Without a MMT understanding the sheep fall for his very precise and careful chosen paragraphs of nonsense.

This idea persists because we haven’t laid out clearly enough that monetary independence means we can put in place a completely alternative stabilisation policy to interest rate adjustments.

Outside of MMT circles there is zero understanding that the buffer stock automatic stabiliser system *replaces* interest rate adjustment as the system stabilisation policy. No longer do we try to influence the economy via the money market. Instead we anchor prices in the labour market and let the money market float.

Truss failed mostly because she was politically incompetent or, at best, politically impatient but also because she bent knee to the money market (largely because she wanted to hide the necessary tax rises as interest rate rises – in keeping with Tufton Street ideology). Get rid of that and let the money market float and it no longer matters what they think. What matters for stability is the price anchor – what government pays in the labour market.

I think, in addition to that, there is going to have to be a political hypothecated tax that shifts any rise in the cost of needed imports (food and fuel mostly) to discretionary imports. We need to make it clear that the primary external balancing mechanism for changes in the terms of trade is a net elimination of discretionary physical imports, rather than the mainstream approach of trying to buy additional financial exports via higher interest rates.

In other words price rises caused by changes in the terms of trade will be end up on luxury imports and that’s where the semi-inflation will be allowed to dissipate.

The limit to monetary sovereignty for net importers is then the quantity of discretionary imports they can eliminate. Once it is all needed imports (food and fuel), room for manoeuvre becomes very limited.

None of this applies to the USA of course – at least not until the reserve shift to the Yuan and gold gathers pace.

I totally agree with your critique.

Just a comment on the phrase “2. The ECB now holds more than 25 per cent of all debt issued by Eurozone governments (see the following graph) as a result of a myriad of government bond-buying programs that began in May 2010 with the Securities Markets Program (SMP) and continue into the present – in multiple forms (APP, PEPP etc).”

It is in fact the national central banks who buy most of that debt. Currently the Bank of Spain owns more than 30% of Spanish treasuries. I know that you are well aware of this institutional arrrangement. But it deserves to be highlighted since it calls into question the idea of a single central bank.

In Portugal, we continuosly hear the liberals talking about “tax cuts”, allegeledly to make the country more competitive, so that we can catch up with coutries like Holand or Ireland, that are tax havens.

But we are an eurozone member and, therefore, we are not an independent and sovereign state.

We must comply with a certain level of tax collection, imposed by the UE (increasingly dependent on the FIRE sector in general and the ECB in particular).

The imposed level of tax collection means that any tax cuts must be met and offset by another adjustment in tax collection – elsewhere!

What the liberals don’t say is who are the ones that are getting tax cuts and who are the ones that are getting tax hikes.

In 2012, they called it the “troika adjustment”.

Others call it austerity.

In either case, we can call it “redestribution of income and wealth” from the 99% to the 1%.

That’s what the euro is all about.

My instincts tell me that Derek Henry is onto the “appeal” of the Eurozone – it suits the rentier elites who control national political economic narratives much the same way that US dollar hegemony suits the comprador elites in the developing world. They dress their self-interest in a gloss of economic orthodoxy that supposedly justifies their policies as in the “national interest” when it is nothing of the sort and actually wholly exploitative of their fellow citizens, especially working people.

But they own the press, the academy and the bulk of the political parties. So it goes …

Dear Bill

Saw a good video by Yanis Varoufakis today: “The ECB is demanding €20,000 from us for ‘legal fees’, because we dared to ask for information that should be publicly available. Let’s fight back their attempt to take the judicial road to authoritarianism – and finally release #TheGreekFiles.”

Also today I was surprised that the Guardian published my letter: “There is little point in James Meadway regretting Keir Starmer’s lack of spending commitments whilst maintaining the fiction that ‘spending increases will have to be met by at least some tax rises'”.

It included this line which I’ve been trying to smuggle into the debate for some while:

“We had the same real resources after the financial crash as we did before. There was never a need for austerity.”

I copied in our friend on the editorial team, so perhaps that’s what did it.

In the U.S., the ridiculously wealthy class has enjoyed four decades of tax cuts and tax loopholes. The result? A strong inflationary impulse that creates ‘boom and bust’ cycles caused by out of control liquidity. First to inflate are financial assets but soon that inflation spreads like a virus to all other prices. Covid just lit the fuse. The inflation was already deeply embedded. In Fed speak, this is called the ‘allocative effect’ where zero interest rates move cash from labor and the middle class up to the wealthy minority. Financial bets move out up the risk curve. Now you know how the U.S. managed to create massive income inequality. I suspect a similar money flow occurs in the EU. My view is that the best weapon against inflation is to tax progressively. Drain liquidity from the ridiculously wealthy class and open up fiscal space for the government to create jobs that benefit the majority of citizens. The best way to provide prosperity was explained by William Jennings Bryan, a populist candidate for President in the 1890s.

“There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that, if you will only legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below. The DEMOCRATIC idea, however, has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them.”

@Chris Herbert,

There is another wat to look at that. If you tax the rich at 90%, then they are more likely to pay their workers more and deduct that from their corp’s revenue, rather than paying it in tax to the Gov. This gives the corps more demand for their product because their workers can buy more. The rich can’t see this though, Corps also invest more in R&D for the same reason.

. . However, we need to reduce consumption because of ACC.

“If you tax the rich at 90%, then they are more likely to pay their workers more and deduct that from their corp’s revenue, rather than paying it in tax to the Gov”

Seriously.

If you tax the rich at 90%, then they will pass that cost onto workers by paying them less. They are not going to pay 10% extra out of the goodness of their own heart. They pay as little as they can get away with.

The rich are rich because they have power. They use that power to pass imposed costs onto others who do not have the power to resist.

Corporations only invest more in R&D than they need to if there is a super deduction – one where they get to deduct more than the amortised cost of the expenditure. With R&D there is a chance you’ll create intellectual property which you can patent and sell at a profit. There is no such ownership over a capital product created from paying workers more.

We had 90% unearned income tax rates in the UK in the 1960s. It lead to decline.

Sandbu forgets that the worst calamity in societies today (apart from threats associated with climate change) is joblessness created either by recessions or by deliberate policy to fight inflation. A sovereign currency country has always the capacity to simultaneously use employment buffer stock to deal with inflation and JG to fight unemployment. Hence, its superiority versus Eurozone countries.

@ Carol Wilcox, Bravo for breaking into the pages of the neo-liberal EU love-in. One has to be positive and believe that small prods are worthwhile despite the torrent of nonsense, especially left in comments. Unfortunately the neo-liberal progressives were back in charge of the Editorial Office today; ‘ .. a one-off wealth tax. Levied at 1% above an individual’s net wealth of £10m, it would raise about £43bn from 22,000 wealthy people.

The cash could, without increasing the budget deficit, be used…’. The opinion signs off by saying to do better ‘require a clear-headed analysis and bravery’.

@ Neil Wilson re: ‘We had 90% unearned income tax rates in the UK in the 1960s. It lead to decline.’ Firstly, income tax is on earnings and it was cut to 75% in 1971 (I’m going by wiki). You’ll have to offer up a lot more to convince me that higher income tax rates were the main cause of a 60s decline. Capital gains tax was only introduced in 1965 and then only at 30%. Nigel Lawrence aligned the rate with income tax, only for Gordon Brown to reduce it. I take your point though, that high earners will keep working at 90% tax, and pass the tax cost on, even if they are just receiving 10% of the extra pay above the previous threshold. Perhaps a 99% tax rate would persuade them not to earn just to have the government take so much money out of the system. Regulating so that top earnings couldn’t be multiple multiple times the earnings of other workers might be a better alternative.

Anti-fragmentation measures are MMT-style sovereign bond purchases by the ECB that allow Eurozone countries to issue debt without increasing their national interest rates. It is, ironically, the implementation of this sort of MMT-style yield curve control that makes the Euro attractive to potential new member countries. Countries can issue debt at low rates as if they had monetary sovereignty because the ECB acts as both a zone-wide central bank and, using anti-fragmentation measures, as a national central bank for specific member countries.

“You’ll have to offer up a lot more to convince me that higher income tax rates were the main cause of a 60s decline.”

I didn’t say it was the main cause.

The tax rates peaked at 95% – hence The Beatles song “Taxman”.

It didn’t provide any boost to the system. The decline continued and accelerated. It doesn’t cause employment – because, as MMT teaches us, the purpose of taxes is to *eliminate* private sector employment so there is somebody for the public sector to hire.

Reply to Steve_American Neil and Patricia:

For me the income tax debates are bad distractions. They take eyes off the purpose, which is what Neil sated – to move resources from the private sector into the public sector (and to act as punitive and/or redistributive mechanisms). If we (MMT) claim those are the purposes why the hell are wages getting taxed at all?

It is a game of give with one hand, take with the other, and incurs a massive waste of human labour in the tax evasion industry. Better to functionally target tax liabilities so real resources are not depleted and the private sector cannot rapaciously extract just for profit. A blanket corporate tax hike or wealth tax fails this purpose, being too diffusely targeted.

Well, the low tax rates have left the rich with enough money to buy the government. Seems like an important resource to me.

Though I guess a different way of looking at it is that the low tax rates are a sign that the government has no power over the ultra-wealthy, and can’t exercise sovereignty.

A high corporation tax rate and nil tax on (real) earned incomes gives worker-owned co-ops an advantage over other businesses. There are practically zero examples in the UK which can serve as models. Lots more in the US.

Such co-ops expropriate nil economic rent, an objective of good government IMO.