I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Reinstating our monetary policy obsession

Australia is already heading the charge back into the neo-liberal macroeconomic policy orthodoxy, which caused the financial crisis that has seen millions of jobs shed and poverty rates sky-rocket around the world. Next Tuesday, the central bank will surely increase its target rate of interest again because it is worried about the inflation genie escaping again. When actually did we last have an inflation problem anyway? The problem with this strategy is two-fold. First, it is highly unlikely that monetary policy does effectively operate as a counter-stabilising force. It has distributional effects clearly which punish low income earners but they not the cohort driving the housing prices, for example. Second, it forces fiscal policy to play a passive role so there will be even greater pressure on the government to start winding back the fiscal stimulus. More pain ahead on both fronts.

Tony Joe White has a great song – Taking the Midnight Train:

Taking the midnight train

Taking the midnight train

I can’t stand this pain

Just can’t stand this pain

To have somebody hurt me for no reason

for no cause, for no cause ….

That is what I think about monetary policy … it just hurts the poor and has no defensible reason behind it.

The increased discussion in recent days about the likely direction of interest rates next week follows yesterday’s ABS CPI data which revealed that all measures of inflation are easing. But that isn’t going to be good enough for the RBA, who believe that their actions have no long-run negative impacts on employment or output.

News Limited Senior Economics writer, Michael Stutchbury opened his commentary this morning with the following:

INFLATION is easing. But not fast enough for the Reserve Bank, which is set to lift its official interest rate again … [next] … Tuesday. Another 25-basis-point rise … would be aimed at the central bank’s stubbornly high measure of underlying inflation.

The ABS headline rate was a very low 1.3 per cent per annum while the so-called core inflation rate was 3.5 per annum. For those who are unfamiliar with the distinction between core and headline inflation estimates here is a brief explanation.

The CPI is a relative cost measure of a chosen basket of goods and services that capital city households purchase. It has around 100,000 goods and services included across 11 categories and 90 expenditure classes. The latter are weighted by their importance in the households’ budgets. Periodic revisions are made to the basket to reflect changing patterns of consumption.

The headline inflation rate is the change in the CPI measure. Sometimes seasonal events influence the headline inflation rate so that the impact of a good or service may increase/decrease the inflation rate even though there is no intrinsic change in value. Seasonal booms and busts in food commodities is an example.

The RBA publishes what it calls the core inflation rate which attempts to expunge these “volatile factors” and present an underlying inflation rate. The resulting series published by the ABS are referred to as the trimmed mean and weighted median.

The differences between the two are as follows. The trimmed mean is computed as: (a) order the percentage changes in all CPI classes by relative magnitude; (b) exclude the top and bottom 15 per cent of classes; and (c) create a weighted average of the remaining 70 per cent. The weighted median is then derived as the price change that is in the middle of the 70 per cent centred observations.

When you hear the measure “core inflation” it is usually referring to the average of the trimmed mean and weighted median.

Here is a good introduction to some of these concepts although the underlying understandings of how the monetary system operates are flawed.

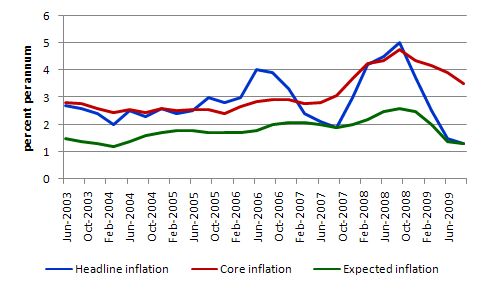

The following graph shows the evolution of the two inflation measures in addition to the NAB inflation expectations series since June 2003. All series are expressed in annual changes. You can see that the inflationary process is not being driven by inflation expectations and the downturn has firmly brought the spike in inflation at the top of the commodities boom back to low levels.

It doesn’t look like an inflation breakout is around the corner any time soon.

Further, there are a number of problems with the derivation of core inflation measures which I will not go into in this blog. While the way the RBA derives its estimates is comprehensible (that is, relatively easy to understand) is remains arbitrary. Why trim the bottom and top 30 per cent? Where did that threshold come from?

However, the more technical methods of estimating the underlying price movements rely on fairly incomprehensible signal processing techniques (that is, difficult for the public to understand) and also usually impose theoretical concepts such as long-run neutrality on the models that generate the estimation equations. This, of-course, is the ultimate neo-liberal myth (the real sector is not affected by nominal changes in prices) and essentially assumes away unemployment.

Why is the core rate even mentioned in the public debate? Because it is the rate that the RBA uses to assess its monetary policy. Under its misguided inflation-targeting approach it considers a core inflation between 2 and 3 per cent to be acceptable. So even though the estimate of core inflation is falling it remains above 3 per cent and with the RBA convinced the recession is over it claims it has to start hiking rates again.

However, one of the leading commercial banks argued today that the RBA was starting to hike rates far too early. They said:

… further interest rate rises could be a setback for the nation’s fragile economy, calling on the Reserve Bank to wait until after Christmas before it pushes ahead with its tightening policy.

I note further negative commentary this afternoon from the housing industry lobby who rightfully point out that the so-called impending housing price bubble is not likely to happen and the recent upward movements in housing prices has been driven by the first-home buyers grant (part of the fiscal stimulus package), which is now being withdrawn (not before time) by the Government.

There is also tension among central bankers forming around the world about whether inflation targeting provides them with an excessively narrow policy ambit given that it failed to help them see the financial crisis coming which has devastated employment in many countries.

It is interesting to reflect on a speech made by the Bank of England Governor Mervyn King to the Lord Mayor’s Banquet for Bankers and Merchants of the City of London on June 17, 2009. King essentially indicated that the crisis had forced the Bank to broaden its concept of monetary policy. King said, in part, that:

As activity returns to more normal levels, the outlook for inflation will pick up. And it is the outlook for inflation that will guide decisions on the pace and timing of a withdrawal of monetary stimulus … Inflation targeting is a necessary but not sufficient condition for stability in the economy as a whole. When a policy is necessary but not sufficient, the answer is not to abandon, but to augment, it. Indeed, the overarching lesson from this crisis is that the authorities lacked sufficient policy instruments to take effective actions.

I don’t think inflation targeting is necessary at all – see the blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this. But the Bank of England Governor is now signalling that he thinks monetary policy should go beyond the narrow ambit of inflation targeting because as he notes “Setting bank rate to maintain price stability was successful in itself, but did not prevent a recession induced by a financial crisis”.

So what is the RBA likely to do?

News Limited writer David Uren said the following this morning:

… many market analysts believe the Reserve Bank is likely to aim for a 50-basis-point move – the biggest increase in cash rates since February 2000 – in an effort to get on top of inflation before it gets out of control.

It is clear that the quarterly rises have been rising over the last year. But this has to be assessed in the light of the major jump in electricity, gas and water prices in the current month’s data. These increases are not on-going and so the spurt in inflation in the last quarter is unlikely to reflect the underlying trends.

There is also external factors that need to be considered. Our interest rates are well above those of Britain, the US, Canada and Japan and this puts upward pressure on our exchange rate.

There are two impacts. First, imported price inflation is reduced but the exchange rate reduces the competitiveness of the traded-goods sector. This points to one of the problems of inflation-targeting in an open economy. When the “fight is on” there is always upwards pressure on the exchange rate.

From a modern monetary theory (MMT) perspective this is no real issue because it just means that imports are cheaper. Within MMT we consider exports to be a cost and imports to be a benefit. Some people might think that this implies we should be using our exported goods and services ourselves and only send them abroad when we want to derive foreign exchange to purchase imports.

For Australia, the argument is less applicable given the majority of our exports are mining and agricultural products which are of less use to us, especially given our lack of an industrial base. This applies less to the agricultural goods, of-course. However, significant proportions of those are meat products and the vegetarian camp within MMT (me!) would not want those products diverted to home markets!

However, the point is that declining international competitiveness makes imports cheaper and frees labour up from the pressured export sectors to work elsewhere in the non-traded goods sector.

But from the mainstream perspective, the rising appreciation is surely a problem. They probably construct their argument in terms of a re-emergence of the commodities boom, which will boost demand via net exports and then promote inflationary impulses into the domestic economy.

This is what the RBA Governor said last year at a Treasury Seminar Series (March 11, 2008):

Looking across the economy more generally, we can all see that the main external event of recent years is the rise in the terms of trade, which is obviously completely exogenous as far as Australia is concerned. But higher resource prices generate additional income, which then affects demand for goods and services at home. That is expansionary, and puts pressure on prices for non traded goods and services. Even though monetary policy cannot stop the initial shock – of course we cannot stop the Chinese demand for resources – we can, and should, seek to condition the economy’s subsequent response to that shock, rather than simply letting domestic overheating go unchecked. Tighter policy will dampen domestic demand and contain the pick up in non traded prices as well as raising the exchange rate, which makes imports cheaper, exports less competitive and fosters a move of productive resources into the parts of the economy where more production is needed. That is an appropriate form of adjustment to such a shock, particularly if the shock is likely to be fairly persistent.

This argument is fairly unconvincing given that the most recent boom was occurring while the non-mining regions of Australia, particularly NSW was undergoing a major slowdown even before the financial crisis hit.

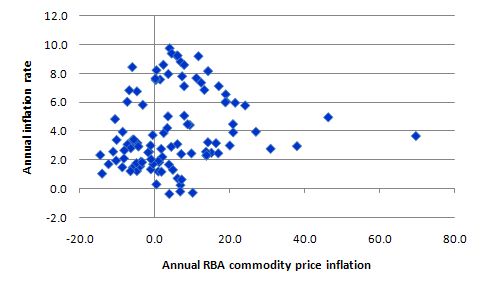

The following graph shows the scatter with annual changes in the RBA commodity price index (horizontal axis) and the annual CPI inflation rate (vertical axis) since September 1983 (so before inflation targeting). It is hard to detect a very systematic relationship between the two. The RBA might argue that that is because their policies have intervened, which is not disputable from an examination of the graph alone.

Whichever way you twist yesterday’s CPI figures, I find it hard to see an inflation outbreak looming.

The RBA touts the notion of a neutral inflation rate (which we have critically assessed . It will not publicly state what its estimates of the “neutral rate” is but the previous Governor indicated it was between 5 and 6 percent.

The estimates are typically derived from models which assume long-run monetary neutrality – a patently false scenario. This is just an assertion that parades as credible theory. It has about as much rigour as the NAIRU concept – which means there is no rigour – just made up stuff.

The other thing I dislike about central bankers who make policy which impacts on our lives but refuse to disclose the basis of those decisions is that it is inherently undemocratic. They are not elected. We (the people) are not in a position where we can force them to take responsibility for their decisions. At least we can chuck out the national government every 3 years.

Anyway, assuming they think the neutral rate is between 5 and 6 per cent, then the logic of their position is that until they get to that monetary policy is still expansionary. At present, the target rate is 3.25 per cent, so they have a way to go before they consider monetary policy to be neutral.

This brings into relief the nonsensical characterisation of what they think they are doing. If inflation pressures are mounting then they will just mount more slowly but still escalate if you believe their logic until rates are above 6 per cent or so. What model of inflationary pressures do they have which tells them that the breakout will

It cannot be based on the behaviour of price expectations which according to the graph are not going anyway at present. This was always their argument that they would need to signal a sequence of rate rises into the future to bring expectations down. That is not a factor at present.

So they must think that aggregate demand is going to have to be stalled in about 15-18 months (given it will take them that long I suspect to get back to 6 per cent). But then they must thing the output gap will be closed by then.

With 14 per cent of our labour resources currently underutilised and capital utilisation rates below 70 per cent, they must be banking on a very rapid recovery to think GDP growth will be anywhere near potential by the end of that period.

Many commentators are arguing that rates have to rise because housing is now booming. Apart from the fact that using monetary policy is not a good way to target an boom in the price of a specific asset class (see this blog for a discussion on that topic), there is clearly mixed evidence on the housing front.

Additional information from the Housing Industry Association published today shows an easing (4.5 fall) in new home sales. This was predictable given that the first home buyers grant scheme is started being wound back as noted above. I think the fiscal withdrawal from this market will have ongoing dampening effects.

Why should we be concerned?

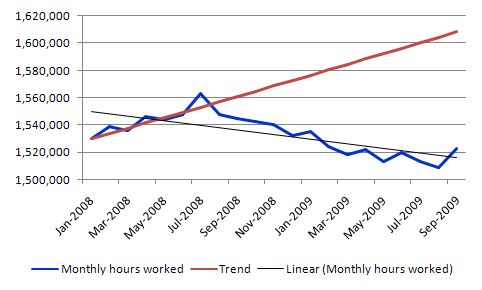

While unemployment is hovering around 5.8 per cent at present, the trend in total hours worked remains negative. The following graph is taken from the ABS Labour Force data and shows total monthly hours worked since January 2008 (one month before the low-point unemployment rate in the last growth cycle was achieved). I just extrapolated the average growth rate for the preceding two years out to September 2009 (red line). The thin black line is the simple trend regression line for the actual time series which is shown in blue.

Male working hours have dropped by 2.3 per cent on the April 2008 peak, whereas female hours are down by 0.3 per cent. In total hours have dropped by 1.5 per cent. If you express this in terms of full-time equivalent (40 hour per week jobs) the decline is equal to 137 thousand male jobs, 12 thousand female jobs and 148 thousand total jobs that have been deleted from the Australian economy. This stands in contrast to the net changes in measured employment in persons over the same period of

-3.9 thousand male jobs, plus 29.6 thousand female jobs giving a net total increase in employment of 25.7 thousand.

This is why I have termed this recession the underemployment downturn in Australia. It has been characterised by a major adjustment in hours worked rather than persons unemployed.

However the point is clear – things are still looking very bad in the labour market. The worst affected are the lowest paid workers. Any rise in interest rates will further damage their living standards.

The uncertainty about how monetary policy works and the questionable distributional assumptions that are relied on in the modelling all suggest to me that it is a poor counter-stabilisation vehicle. But, moreover, the concept of counter-stabilisation was perverted under the neo-liberal ideology to mean inflation stability and sacrifice real growth and employment in pursuit of price level stability.

In that sense, while rising interest rates are unlikely to dent the growth much in the immediate future they will immediately damage the poorer workers. Further, given the past record of the RBA rates will rise to the point of threatening the viability of the household sector which is still carrying unsustainable levels of debt.

Further, there will be increased pressures on fiscal policy to contract to “support the inflation fight” and that will further weaken our recovery and undermine our growth potential. Lower productivity and lower real wages growth has accompanied the inflation targeting period as has persistent labour underutilisation.

It is one of those con jobs that the mainstream of my profession have inflicted on the innocents – all of us. We will look back on this period of history with aghast – “how stupid those humans were in those days” will be the topic at the dinner table.

Digression – 40 years today …

I was a teenager listening to Then Play On (Fleetwood Mac), Blues from Laurel Canyon (John Mayall), Electric Ladyland (Jimi Hendrix), Bitches Brew (Miles Davis) and Led Zeppelin One.

I was playing in a band called Simon Black (from memory).

And the first packet switching message was sent between remote computers at 10.30 on October 29 (today). This was performed on the Cold War inspired ARPANET and was sent between UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute in Northern California by a graduate student.

The login attempt failed – only the L and O letters were transmitted. But later that day the transmission succeeded and what we know as the Internet was born.

This Post Has 0 Comments