I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

CofFEE conference – Day 1 report

Today is the first day of the 11th Path to Full Employment Conference/16th National Unemployment Conference in Newcastle, hosted by my research centre. As host I am of-course tied up in the event but I thought it would be of interest to visitors to my blog to provide some feel for what has transpired today. I only focus on the plenary talks. The other presentations in the parallel sessions have all been very interesting.

The Conference brings together participants who work in the financial markets (funds managers, bankers etc); those who work in labour market policy; those who work in national statistics offices; those who basically research these issues (such as myself); those who work in the field (in international agencies, consultants etc). So it is a very interesting gathering. The ivory tower types meet those who are on the ground which is an essential reality check missing in most mainstream economics.

For example, modern monetary theory (MMT) is very different from mainstream economics because it is are combination of expenditure theory (some might call this Keynesian – I would not) and the operational realities of the monetary system.

Anyway, this morning Marshall Auerback, who is a funds manager with RAB Capital in Denver, USA started the Conference by arguing that is was Time For a New “New Deal”. He argued that Roosevelt’s New Deal program is often misunderstood and/or mispresented by both neo-liberals who want to construct it as a failure of government policy and progressives who typically argue that the onset of the World War 2 was the even that finally ended the depression.

He argued that part of the problem – apart from venal revisionism – is that many researchers use statistics which understate the number of jobs that were created under the New Deal.

Even pro-Roosevelt historians such as William Leuchtenburg and Doris Kearns Goodwin have meekly accepted that the millions of people in the New Deal workfare programs were unemployed, while comparable millions of Germans and Japanese, and eventually French and British, who were dragooned into the armed forces and defense production industries in the mid-and late 1930s, were considered to be employed. This made the Roosevelt administration’s economic performance appear uncompetitive, but it is fairer to argue that the people employed in government public works and conservation programs were just as authentically (and much more usefully) employed as draftees in what became garrison states, while Roosevelt was rebuilding America at a historic bargain cost.

More careful examination of US Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that, in fact, “If these workfare Americans are considered to be unemployed, the Roosevelt administration reduced unemployment from 33 per cent in 1933 to 13 per cent in 1936, to less than 10 per cent at the end of 1940, to less than 1 per cent a year later when the U.S. was plunged into the Second World War. If the federal workfare employees are accepted as employed, the corresponding numbers are 33 per cent, 7 per cent, 3 per cent and 0.5 per cent.”

The New Deal did falter in 1937 as Roosevelt’s conservative Treasury secretary held sway and persuaded the Administration to introduce a contractionary budget. Within a short-time unemployment rose by more than 3 per cent and Roosevelt resumed the expansionary strategy which then further drove down unemployment.

The onset of the Second World War definitely mopped up any residual unemployment and demonstrated categorically how powerful and direct fiscal policy was in addressing business cycle fluctuations.

The paper pushed the debate into the current period and indicated that the major constraint on creating enough jobs to fully employ the labour force are political rather than economic. For a sovereign government that faces no revenue constraint they can always create enough jobs. The fact that they are refusing to do that indicates the political power that the deficit terrorists are exerting in the US administration.

The second plenary address today came from Dr Jesus Felipe, Principal Economist in the Central and West Asia Department, of the Asian Development Bank who has just published a book entitled Inclusive Growth, Full Employment, and Structural Change: The Dilemmas. You can see Jesus speaking about his book on You Tube. Jesus and I are working together on projects in Central Asia at present and I wrote the foreward to the book.

Here is a snapshot of my foreward. The entire world over poverty is closely related to unemployment and underemployment. This is especially the case in developing Asia where about 500 million unemployed and underemployed people have to cope without significant government welfare support. Recently, institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank have started using the term inclusive growth in setting their policy agendas. Jesus’s book argues that if policymakers across developing Asia care about inclusive growth, which is defined as growth with equal opportunities, then achieving true full employment should become the paramount objective of Asian governments.

The best strategy to reduce poverty in developing Asia is to introduce a set of policies that will generate full employment. While a number of policy initiatives will be useful – particularly those that target productivity improvements in agriculture; stimulate investment in industry; expand education attainment and technical skills formation; and those that condition the broader macroeconomic environment (monetary and fiscal policy and exchange rate policy) – all must be coordinated to ensure they are pulling the economies in the same direction – towards full employment.

The policy mix is important because ongoing structural change, the key to development, makes the attainment of full employment a moving target and government s are continually confronted with political and economic choices which at times seem to be conflicting. But at all times, the policy process must aim to ensure there are enough jobs available to meet the needs of the labor force.

Agriculture remains the largest employer in many Asian countries, including the two largest developing economies, i.e., India and the People’s Republic of China. It is thus clear that any viable development plan must place special focus on agriculture. Any viable plan has to involve investment initiatives to improve agricultural productivity and alternative job creation strategies to provide opportunities for rural workers displaced by these technological advances. These job creation initiatives must partner structural change if full employment is to be achieved. Localised job creation programs will also be necessary to ensure that urban structures are not flooded with workers displaced from the modernized agricultural sector.

In this regard, the conduct of fiscal and monetary policy at the aggregate level will be crucial in how successful each nation is in achieving the aim of inclusive growth. Ultimately, full employment is the responsibility of the national government. While the private sector makes a significant contribution to employment growth across all economies, it remains a fact that this sector still never provides enough jobs to satisfy the desires for work by the labor force.

In this regard, the public sector has a strong role to play as a direct employer in its own right, in addition to providing a policy framework that maximizes private employment growth. However, in recognizing this, it also follows that the policy target has to be firmly set on implementing policies that deliver full employment and price stability. When considering the conduct of macroeconomic policy, the neo-liberal era has been marked by a focus on low inflation and certain presumptions national budget deficits.

During this era, unemployment has become a policy tool to reduce inflation rather than a policy target and governments have been encouraged to generate budget surpluses. There is a solid body of evidence available that indicates this strategy has not delivered sustainable growth in any country and has, particularly damaged the developing countries of Asia.

Jesus demonstrates that the policy targets should be realigned to be full employment and price stability and that the size of budget deficit should not be considered a policy target, but, rather, an outcome of what is required to achieve these other overarching goals.

So he is operating from a macroeconomics perspective within the MMT tradition.

To make progress towards that goal, budget deficits must be demystified. Reliance in recent decades on monetary policy to stabilise the business cycle (with the concomitant requirement that fiscal policy becomes passive) has failed to deliver outcomes consistent with the goal of inclusive growth.

To remedy this, fiscal policy has to resume primacy among the aggregate policy instruments and be used to ensure that private savings can be financed. Another more conventional way of thinking about this is that when the private sector desire to save some of the national income, aggregate demand will be insufficient to fully employ the workforce unless net government spending fills the spending gap. In this way, the budget deficit serves to provide the spending necessary to generate the income which finances the saving. As a consequence, any particular budget outcome will be market-determined by the desired net saving of the private sector. If the private sector desires to save less, then the resulting budget deficit will be smaller and vice-versa.

What are the limits on the size of the budget deficit? Sound fiscal conduct will ensure that aggregate spending (the sum of private and public demand) is sufficient to achieve full employment. If fiscal policy stimulates nominal demand beyond this point then inflation necessarily follows. National governments should thus feel comfortable running continuous deficits within this limit in the knowledge that they are underpinning private saving and also maintaining full employment.

In addition to recognising the essential role of net government spending in stabilising aggregate demand, many developing countries also need fundamental fiscal reforms aimed at increasing the efficiency of the public sector so that more resources can be allocated for productive investment and/or direct job creation. The two insights complement each other.

Strong fiscal policy is essential but so also is an effective use of the resources that the government deploys.

While full employment was an objective of central banks and governments across the developed world between the end of World War II and the 1970s, during the last 30 years this goal has been abandoned. The results of this regime shift in policy practice have been that most countries have been forced by their governments to endure persistently high unemployment and rising levels of underemployment.

While the income losses associated with persistent labor underutilisation have been huge and dwarf any measured costs of so-called microeconomic inefficiencies, the related social pathologies have also been significant. Increased rates of family breakdown, escalating crime rates; rising drug abuse; and, arguably rising political instability and extremism have all been closely tied to entrenched joblessness.

While these costs are disproportionately borne by the most disadvantaged members of our communities, the externalities that arise (for example, crime, terrorism, etc) affect us all. However, the public debate, which has been significantly conditioned by neo-liberal commentators, has tended to consider unemployment as a personal issue rather than a systemic failure of the economy to generate enough jobs. In this respect, the debate has placed too much stress on inflation and downplayed the costs of unemployment, which are of a higher order of magnitude than the costs arising from mild inflation levels.

Jesus argues that no rigorous evidence is available to show that mild inflation damages the economy to an extent that would justify it as the key economic policy concern and induce policy makers to use sustained high unemployment to control it.

Much of the economic debate surrounding inflation has misrepresented the underlying causality. An inflationary process caused by effective demand hitting full capacity during an economic expansion is significantly different from what happened in the world during 2007-2008. In the first case, the economic bonanza would probably lead to an increase in employment and wages, and necessitate economic policy being used to dampen nominal demand sufficiently to keep the real economy as close to full employment as is possible.

However, this situation does not describe the 2007-2008 inflation episode in developing countries. The combination of increases in oil and food prices has brought misery to millions of people around the world. The additional problem is that the inflation is coincident with a major slowdown in the world economy that started in the developed countries (especially in the United States). There is clearly a different approach being adopted by the US Federal Reserve relative to how the European Central Bank is seeing the problem.

The former have lowering interest rates significantly in an effort to reactivate economic growth while the latter up until late 2008 maintained a firm focus on controlling inflation. It is only as the global economic crisis has deepened significantly, that the G20 nations have demonstrated the semblance of a untied strategy aimed at stimulating demand to protect jobs.

Further, the ultimate driver of the increase in oil prices is still not entirely understood. But it is a combination of the control that the suppliers have on price combined with the massive growth in demand from the People’s Republic of China’s and India’s that have driven oil prices higher. There is also evidence that financial institutions (hedge funds etc) have been hoarding oil and using it for speculative purposes.

What about food prices? Early on it was said that the price increases were due to poor harvests in some key countries, in which case they should be a temporary phenomenon. We were told that the situation was probably leading to inflationary expectations and that sooner or later workers would demand increases in wages. The reality, however, is that central banks do not have solid knowledge about how their own actions affect inflation expectations and how these in turn affect inflation. Little is known about firms’ inflation expectations and how, if at all, these beliefs influence pricing decisions. The point being made is that before we can design and implement effective policies we need to understand the underlying economic and social processes that are combining to generate these problems.

As indicated earlier, over the last three decades there has been an important change in the way the public debate constructs unemployment and its causes. Previously, unemployment was thought to result from insufficient aggregate demand – that is, a systemic failure beyond the control of any one individual. In recent times, individuals are now deemed to be responsible for their own economic outcomes: people are unemployed because they have not invested in the appropriate skills; because they have not made an effort to search for jobs; or because they have become too choosy in what they might consider doing.

Further, the policy structures that were implemented during the full employment period to provide support to workers who were temporarily unemployed are now considered to be complicit in sustaining unemployment. So critics of government suggest that welfare provisions are excessively generous which distort individual decision making towards unemployment.

Developing Asia has been experiencing fast growth rates for decades and is the envy of most other regions in the world. However, Jesus shows that this perception is lopsided. While high growth is seen as the key parameter for evaluating developing Asia’s success, there is abundant evidence that this growth is not translating into sufficient job creation. In particular, labour absorption by industry is low and most of the new employment is being created by services.

So this period of development is seeing workers being transferred directly from agriculture into services without an industry base being developed. This is a significant departure from the standard path that development follows. It is clear that policy makers across developing Asia need to understand these trends, to avoid the pitfalls that it is likely to present as time passes.

The book spells out the main constraint that many countries across developing Asia face for their development: a lack of capital equipment and productive capacity. Therefore, the purpose of development must be to increase a country’s productive capacity in order to achieve the full employment of labor. However, rapid structural transformation, competition, and globalisation limit the capacity and autonomy of Asia’s developing countries to achieve full employment without significant public sector involvement.

Despite the political and technical difficulties in achieving and maintaining full employment, governments across the region should not be deterred. In the final analysis, unemployment and underemployment are states that can be largely prevented by sound government policy. The motivation by policy makers to pursue full employment should be conditioned by the desire to maximise incomes; by the desire to ensure human rights are maintained; and by the desire to achieve social stability.

Allowing high rates of unemployment to persist reflect a diminution of government responsibly and leadership. The decision to pursue full employment policies requires political choices to be made and for the government to engender a sense of collective will. Over the three decades, governments have progressively tried to undermine this collective approach.

While full employment can be constructed as a human right it can also be constructed as a rational public choice for other reasons. An economy running at full employment or “high pressure” maximises income creation. This leads to more buoyant markets, businesses, investment, and employment. This is an economy that will provide everyone with opportunities.

The late John F. Kennedy coined the phrase “A rising tide lifts all boats” which recognises the upgrading benefits of the high pressure economy. Governments who use fiscal policy to ensure their economies stay as close to full employment as possible generate massive advantages where both the strong and the weak prosper. Labor participation is strong, unemployment is at the irreducible minimum, labor productivity is high, wages are high and a number of upgrading effects across social classes and generations occur.

Children from disadvantaged families get a chance to transcend poverty and workers who are displaced by global economic changes are able to be re-absorbed into productive work. Direct public sector job creation is a significant part of the national government’s responsibilities in this regard.

So a fully employed economy delivers great individual and social benefits. Unemployment and underemployment have direct economic costs and lead to poverty, misery, malnutrition, and social injustice. Persistent unemployment and underemployment act as a form of social exclusion that violates basic concepts of membership and citizenship, thus prohibiting inclusive growth. Full employment in the developing world also contributes to political stability, as the consumption of much of the population will be higher than when many people are unemployed. It should be an ethical imperative in today’s world. As a consequence, a rational person will rightly note that developing countries cannot afford unemployment and underemployment. This construction is eminently more plausible and evidence-based than its opposite – that they cannot afford full employment.

Finally, while the private sector is the generator of wealth and most employment in a market economy, governments should be held accountable for their efforts and commitment to achieve full employment.

This follows from an understanding of the policy options available to a national government. But it also reflects the observation that when the unemployment rises, the public always blame the government rather than the private sector.

Overall, it is clear that governments and the private sector must collaborate strategically to generate a fully employed economy. Both strong investment from the private sector and a strong commitment from the public sector to job creation and public infrastructure development are necessary to achieve this goal.

As an aside, Jesus and myself are working on a new book on developing economies to offset the neo-liberal literature that has emerged in the recent years which claims that government involvement in the development process is actually harmful, which is analogous to the natural rate-type arguments in advanced countries where the free market economists argue that governments cannot reduce unemployment below some “natural” rate without causing inflation. The natural rate is of-course an asserted construct which defied measurement and whenever unemployment rises, the conservatives tend to come up with new higher estimates of the “natural rate”. All of the estimates of this natural rate resemble the actual rate.

The last plenary talk for the morning was from Professor Robert McCutcheon, University of Witswatersrand, South Africa who spoke of A Comparative Study of Five Country Specific Labour – Intensive Infrastructure Development Programmes: Policy Implications for Sub Saharan Countries including South Africa.

Robert is a civil engineer who I met last year while I was working in South Africa evaluating their Expanded Public Works Programme. It was an interesting coming together because Robert, as an engineer was captivated by the ideas that emerge from MMT after he had worked throughout Africa for many years on road-building projects and continually heard comments about projects being financially constrained. For me, it was interesting to meet a civil engineer that was fighting against his own profession in terms of his advocacy for labour-intensive infrastructure projects.

MMT tells us that a sovereign government has no financial constraint. This means that claims by treasury departments in governments that they cannot afford to hire more workers to build more roads are “artificial” and erroneous constraints on the development process.

So then you have to consider different questions. It was noted at the end of his presentation that financial information is useless for appraising government performance – so there is no information in the statement that the budget deficit is 3 per cent of GDP as opposed to 4 per cent of GDP. The real concern is to focus on what actually has been achieved with a 3 per cent deficit relative to a 4 per cent deficit. A good place to start that evaluation is to consider employment and unemployment levels.

The point is that the media presentation of economic data has been totally biased towards meaningless financial data – what is happening on the share markets, or what the Nikkei was overnight, etc. What we should be informed of is how many jobs were created that day and how many people are left without enough work. Other “real” matters could also be highlighted in our news bulletins.

Robert’s experience is also of interest to those (such as myself) who desire to introduce employment guarantees which are operationally effective – that is, the maximum number of people get employed (all those who want a job but cannot find one); they all enjoy secure incomes; they undertake productive (broadly defined) tasks; and they receive opportunities to train for new skills by choice.

As an engineer he has continually been struggling against other engineers who want to build roads with the latest machinery – the problem being that this technology is highly capital intensive and therefore employ very few people per km of road built. When confronted by the idea that the same roads could be built – to the same quality specification – but with labour intensive methods, the public works engineers are confronted and reject the suggestion.

I had first-hand experience of this in South Africa last year when I was told that the country was aspiring to be a sophisticated nation and should be using labour intsensive techniques. The problem is that Apartheid created a very binary model of development. Parts of South Africa are like any place you would visit in the first world – very advanced. But the rest of the country – the majority, in fact – is virtually undeveloped with entrenched poverty, joblessness, poor housing, no roads, etc.

So a sensible national building strategy is to use technologies that suit the stage of development that the policy makers confront. So it is perfectly reasonable to produce roads in South Africa using labour intensive techniques. Robert showed – based on his extensive experience in Botswana, Kenya, Ghana and Lesotho – that these labour-intensive programs produce high quality roads and employ thousands of workers. The quality is not a function of the capital intensity.

Later this afternoon we will hear from Professor Philip Harvey from the Rutgers School of Law, Camden, USA, who has a long-standing interest in employment guarantees. He talked about Back to the Future: Learning from the New Deal.

Phillip proposed that if we view the struggle against unemployment as a human rights struggle leads to better economic policies and provides more powerful policy arguments. He also said that our desire for full employment reflects or defines the goals of progressive reform efforts better than alternative formulations.

It also provides a better foundation for the development of economics as a normative science. So economic policies are desirable because they produce outcomes that advance human rights.

Finally, it promotes the political mobilisation by the unemployed. The only way that we will make significant changes towards advancing human rights is if we convince the political elites that such a strategy is necessary. “I am unemployed and I demand my right to work be vindicated. I want a job”. This sort of political statement pressures the elites and in history has forced them to concede and allow policy outcomes that benefit the disadvantage.

Phillip argued that we need employment policies which operate at the top of the business cycle as well as the bottom of the cycle. He noted that even at the high point of the cycle there has been in recent decades significant levels of labour underutilisation.

For example, in Australia in February 2008 (the low-point unemployment month in the last cycle), there were around 9 per cent of workers underutilised – either officially unemployed, underemployed, or hidden unemployed workers. This insight predisposes him to employment guarantees.

We learned that Obama’s fiscal stimulus was slow and inefficient and projected to save only 3-4 million jobs and was thus “very expensive”. Further, after 8 months not much of the $US787 billion has been spent and very few jobs have

been created.

The Obama strategy was a “trickle down” strategy – let’s get the economy moving and then the jobs will come but it has been slow to create any jobs for the unemployed.

The New Deal alternative was conceived by social workers rather than economists with the primary goal of social welfare (meeting human needs) rather than a narrow “get the economy moving” package. It was only a minor pump priming approach which never spent enough to achieve its social welfare goals and only needy workers were targetted. This was because FDR was a fiscal conservative.

But the New Deal approach was “a trick up” strategy where you directly creates jobs which are better targetted and allow for social and human rights. In turn, the extra jobs then create spending multipliers which provide the broader stimulus.

He computed that for $US553 billion you could generate 18 million jobs. Comparing this with the $US787 billion for 3-4 million jobs that is the current Obama strategy – he asked “why does a New Deal policy which delivers so much more for so much less” be not taken up? That is a great question.

Finally, we are launching Jesus’s book at the end of the day.

We will release videos of these main presentations soon and all the presentations will be available in the new year.

Tomorrow we have a special forum on MMT and the video presentation of this 90-minute session will be available later tomorrow evening for viewing.

Overall, it has been a good start – the party last night brought many people interested in MMT, together including some billy blog commentators (Sean Carmody and Ramanan). While the Conference has broad appeal it has become the “annual MMT convention” which allows us to talk a lot about the challenges and developments that we are all working on.

Retail sales in Australia

The ABS released the October 2009 Retail Trade, Australia today and commentators are claiming the very modest 0.26 percentage rise since September is evident that “suggesting consumption was resilient in the face of rising interest rates” (Source).

The three recent policy rate hikes by the ABS were on October 7, 2009 (3.00 per cent to 3.25 per cent); November 4, 2009 (additional 25 basis points to 3.50); and yesterday (December 2, 2009) where the rate was raised to 3.75 per cent.

So today’s retail sales data tells us nothing about the impact of the RBA tightening on retail sales. In recent months, the data shows that for June 2009 there was a -0.72 per cent monthly change; July 2009 (-0.75 per cent monthly change)

August 2009 (0.51 per cent monthly change); September 2009 (-0.21 per cent monthly change); and October 2009 (0.26 per cent monthly change).

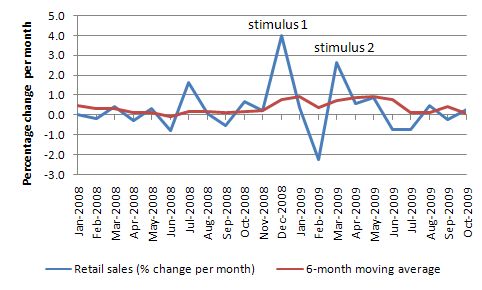

If you look at the following graph, which shows the monthly percentage changes in retail sales since January 2008. The policy impact of the two stimulus packages (December 2008 and February 2009) is very noticable. After that the monthly changes have been trending downwards and the current 6-month moving average is showing that the time series is in decline.

So it is too early to conclude that the monetary policy is not impacting on retail sales. Further, we will not necessarily be able to disentangle the complex distributional impacts of the interest rate changes.

Further, I think the data does show us that fiscal policy which is focused on cash handouts will have a more or less immediate impact on spending but more long-term fiscal initiatives are required which provide those who are unable to spend much some sense of income security.

I also do not see any major spending bubbles emerging from this data, which is now one of the themes that are being advanced by the conservatives to justify further RBA interest rate rises and fiscal policy cutbacks.

for those who couldn’t make it to my conference presentation or who want the full text of my paper then go to:

http://storyofbernadette.blogspot.com/

regards,

Bernadette Smith

I didn’t know it was a such a diverse crowd! I hope I can come next year — it sounds great.

Hi Bill,

> engineers who want to build roads with the latest machinery – the problem being that this technology is highly capital intensive and therefore employ very few people per km of road built.

If I follow this reasoning why not ban personal computers and replace them with old fashioned typing machines to resuscitate the mostly defunct typist profession? Surely this would create thousands of jobs too, but at the same time price IT out of the market.

I do realize that my example is somewhat stretched but it is meant to illustrate the issue of what mainstream economists would probably call “market distortions”. In other words, why should I trust governments to

a) have the ability to draw that the line between good job creating projects and the bad ones.

b) be willing to walk on the right side of that line, such as not serving government officials or a powerful lobby before the people.

BX12, as I understand the issue as presented, it’s a matter of undertaking projects in developing nations where the heavy equipment is not already in place, rather than idling heavy equipment in order to hire manual labor. So it seems like you are attacking a straw man. by suggesting that is in any way comparable to banning PC’s and replacing them with manual typewriters. In SA, it’s a matter of purchasing more heavy equipment or committing the funds to hiring. The wages from the latter would increase aggregate demand in the economy and lead to capital formation and deployment, while alleviating unemployment.

Dear BX12

While I agree with your principle generally, South Africa is not a country that exhibits homogeneous development. The apartheid system created a pattern of development where the white areas were highly modernised and the black areas were extremely “backward” (in terms of advanced technologies, housing, infrastructure, skills etc). I don’t know whether you are aware of it or not but the Bantu Education Act (1953) prevented blacks from developing skills.

Further there are millions of people living in these areas without housing, jobs, incomes … or modern productive skills. So you analogy breaks down. You have to think of South Africa as being two countries in one – which, unfortunately, is what the apartheid system intended to create all along. The residual of that system persists today.

So I recommended the South African government create labour-intensive work for the disadvantaged adults and high quality education for their children as a way to relieve poverty and ensure intergenerational mobility.

Finally, whether you trust governments or not the reality is that they control the monetary system and therefore the economy.

best wishes

bill

The conference was well worth attending, both for the broad range of talks and for the chance to meet a diverse and passionate group of people. I’m sure Bill will get to a Day 2 summary, but a highlight for me was Warren Mosler’s analogy in the Modern Monetary Theory panel discussion. He pointed out that the US Government can no more run out of money than a bowling alley can run out of points to award to players in their bowling frames.

I would have loved to have gone to your conference. If only people really thought like that about economic issues and had so much human dignity and respect for rights to employment it would be a great crowd to hang out with. I mean there are so many people (particularly in African leadership positions) not just in South Africa but all over Africa, that are selfish, corrupt and don’t like comprimise or negotiate and just like to be destructive and destroy others, we really need this kind of thinking that you write about Bill. Unfortunately me being a young, blond, female, that stands up for my rights and trys to negotiate peoblems I do not think I would be welcome at this kind of conference.

Dear Rebecca

Why on Earth would you conclude that as a “young, blond, female … [who] … stands up for … [her] … rights and tries to negotiate problems” be unwelcome at the CofFEE conference? Nothing could be further from the truth.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

I am angry because so much of the destruction in countries such as South Africa and continents such as Africa can be overcome if more people were able to stand up the unfair conditions and policies that are implemented in these places. The developed world has the resources (I believe) to be able to do much more to help developing nations, but it only looks after it’s own interests. The citizens of many developing countries are too scared to stand up for their rights due apprehension and people that can do something don’t care because it dosen’t really affect them, or they can see leaders doing the wrong thing and don’t want to cause a fuss. It’s not right and something has got to be done about it.

An academic studying the contributions of the developed world towards developing nations was trying to tell me after listening to him that all contributions were sufficient and positive and I challenged that and he was so rude and abrupt towards my argument and I felt really upset that I was not being listened to and started blaming myself and questioning my own thinking. Then I realised he was the one who didn’t care and had the problem, again it’s this attitude of lets keep things the same and not do anything about changing conditions such as employment.

Well done Rebecca!, I think you have strayed a bit from the main article but it is good to see somebody looking at our contributions as a developed country in solving much of these problems and I think it is hard to stand up to authority and try to do what’s right, from my experience you usually get isolated and labelled a nut case.

Thanks Judith, I will join your jogging group so I can let off some more steam.

Dear Rebecca (and Judith)

I agree with all your sentiments but you still didn’t say why you would not have been welcome at the CofFEE conference. No-one there would have been rude to you no matter what you said. When an academic gets rude it means they have run out of arguments (which is a typical response to challenge by mainstream economists).

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill,

It might be an idea for all of us to go sometime in the future. I looked at the program, and there are some interesting issues raised that I don’t have a great deal of information on, including issues such as the financial crisis.

I don’t know anyone who went to the conference personally so I shouldn’t relate the behaviour of one academic to all economists. I guess you are right in saying the this academic had run out of arguments, because it was clear to me that he had and the more I thought about it, the more I was convinced that he was wrong.

Rebecca

Dear Rebecca

I would sincerely doubt that any of the academics that came to the CoFFEE conference would treat you like that. There are others that clearly do because cannot tolerate diversity of opinion.

I am sorry you have experienced this intolerance as you are forming your views. But back your judgement and remember when someone will not debate with you it tells you something.

best wishes

bill

Sean/Bill,

Very nice to have met you two. Had a great time at the conference. Yes Warren’s analogy about bowling alleys was excellent. When I introduced myself to Randy, and started discussing about the state of the US economy, he started with the domestic private sector deficit. I thought that was really a good way to start discussing because mainstream economists who are obsessed with government deficits miss the point and the reality is that private sector which has to live with a constraint. Except for a handful of people like Bill, Warren, Randy and colleagues, nobody talks of that even when we are in a crisis which is far from over! Randy also said that it is unfortunate that the official statement is that “it is over” when in fact, there is a lot which is needed to be done.

I liked the discussion session on Day 2 with the theme that the modern monetary system is a public private partnership. I could immediately recall Bill’s post on Operational designs and appreciate more on what that post had to say.

Sean, you missed Bill’s band on Wednesday night!

Dear Ramanan

It was very nice meeting you in person as well.

best wishes

bill