I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Direct public job creation now being debated

In Sunday’s New York Times, the Room for Debate series focused on one of my favourite topics – Should Public-Sector Jobs Come First?. The debate turns out to be very disappointing because even the so-called progressive offerings fall short of advocating an effective solution to the jobs crisis. Only one implies an understanding that the policy design proposed should not be compromised by an errant understanding of the way the fiat monetary system operates. Proposals that assume there is a financial constraint on government will almost certainly be second-rate. The debate could have been energised had the NYT sought expert opinion from those that are developing and implementing large public sector employment programs.

The New York Times editors set the debate up in this way:

… the unemployment rate still hovers at 10 percent. President Obama said on Thursday that he would announce proposals to strengthen employment this week. Some analysts have argued that a new government jobs program would be more effective at putting people back to work than a second stimulus. In a recent Times column, Paul Krugman, called for an emergency program, perhaps “a small-scale version of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration” that would offer relatively low-paying public-service employment …

Should saving these government and education jobs be a priority? Is there a way to establish a public program quickly enough to employ the newly jobless? Would this be an efficient way to stimulate job creation?

Before I consider the individual statements I would recommend everyone read the excellent paper by Melvin M. Brodsky which was published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics entitled Public-service employment programs in selected OECD countries in 2000.

Brodsky says that:

Public-service employment programs … may be the only effective way to aid those among the long-term unemployed who are less skilled and less well educated.

He asks “what will happen to former welfare recipients when the jobs dry up and the safety net provides limited support for the jobless poor.” This statement was in the context of the repressive US Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act introduced by the Clinton Administration in 1996. The Act forced welfare recipients to find work “after not more than 2 consecutive years on welfare”.

While the concern is even more pressing now, it remains that even in good times job buffers which provide a safety nets to the most disadvantaged workers are typically needed.

Brodsky found that countries which assessed both the needs of the unemployment and the local labour market they were operating in before developing job designs were most successful. Further the successful programs were “more flexible, more targeted to local needs, and better linked to other labor market services”.

These findings influenced the operational design of our Job Guarantee proposal. You can read our large Report – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy, which was released this time last year, if you are interested in more information.

I have written several blogs on the optimal design of employment guarantees. This blog – When is a job guarantee a Job Guarantee? – a good place to start. You can also use this Search String to trace other blogs I have written on the topic.

Anyway, now to the NYT’s debate. The first offering came from right-wing economics professor Tyler Cowen who clearly does not support a direct public sector jobs program and considers it would be case of “Expensive Jobs, Too Late”.

He raises the same issue that preoccupies conservatives when public sector job schemes are proposed:

The relevant question is not whether such a program makes sense in the abstract, but rather how a government jobs program will actually turn out, given lobbying, political pressures, and our overly legalistic society.

A new direct jobs program will mean a permanent constituency for a program that should not exist for more than a few years.

Why should the jobs not exist forever? If there is a “permanent constituency” then it defines a need. As Brodsky says these jobs might be the only chance a very disadvantaged workers will be able to participate in paid employment.

If you examine the states that maintained true full employment in the Post World War period you will see that the private sector did not provide enough jobs and working hours to match the desires of the labour force. Even the additional jobs in the career public service did not fill the gap. What was required was a buffer stock of jobs – typically in the public sector which was accessible to the most disadvantaged workers at all times.

Paul Ormerod in his Death of Economics (1994) said (page 203) that the economies that avoided the plunge into high unemployment since 1975 maintained:

a sector of the economy which effectively functions as an employer of the last resort, which absorbs the shocks which occur from time to time …

This is the essence of a Job Guarantee, which is designed to fulfill this absorption function to minimise the costs associated with the flux of the economy.

Tyler Cowen then said that

Ideally, a government jobs program would involve the immediate creation of lots of low-paying jobs, absorbing unemployed workers readily. But we live in a time of public sector unions and costly project delays. The public sector unions won’t like the idea that the jobs can be offered so cheaply. And the projects we come up with will face legal and environmental delays, possibly for many years.

While I cannot speak of the legal system in the US, and Cowen may well be correct (although I doubt it), I see no real constraints on the US government nor any sovereign government offering a job at a liveable minimum wage to anyone who wanted to find one.

Our experience in other countries is that jobs can be designed and labour mobilised very quickly when poverty is the only other available option.

We also know that trade unions do not dislike Job Guarantee schemes as long as they are not pernicious attempts to re-create existing higher paid work under the aegis of the Job Guarantee.

Cowen’s concerns, however, indicate why a permanent Job Guarantee would be preferable to an emergency program. A permanent buffer stock of jobs has the advantage of maintaining a coherent administrative structure which can plan projects well ahead and ensure there are more jobs to be done than workers available.

The second offering came from Jamie Galbraith who is an economists at the University of Texas. He understands most of the principles of modern monetary theory (MMT) (he has had extensive discussions with many of us). Unfortunately, his public comments do not always indicate this. At any rate, Galbraith exhorts us to Think Big on the jobs question.

Galbraith said the:

The question isn’t whether we’ve turned a corner. It’s how do we get all the way back to high employment, even in (say) five years? We’d need nearly 250,000 new jobs every month for 60 months. And without much help from our crippled banks – at least at first.

So the problem isn’t how best to choose between revenue sharing, infrastructure, public jobs and a payroll tax holiday. It’s how to get all those things done – and also how to support small business and non-profits, to help students and to ease older workers into retirement.

I agree with this prioritisation. With share markets rising, and GDP showing signs of positive growth, the mainstream debate has moved onto worrying about when the deficits will be cut.

But, meanwhile the labour markets in most countries (including Australia) are far from healthy. I am amazed that we didn’t blink an eyelid when governments around the world pumped billions into the failing financial markets (and billions of that has been expropriated by the wealthiest individuals in our societies for their own aggrandisement) – yet we have deep fears if a billion or two is proposed to be spent on actually underwriting the incomes of the low-skill workers who are without work.

Galbraith also notes that FDR introduced a bevy of targetted programs to address the jobs crisis during the Great Depression. He notes that there can be no question that idle resources exist and concludes that:

So long as we have people who need jobs, we should find them work. There are better and worse ways to do this, but the money isn’t a limit: it’s just a tool to get the job done.

And if we do too much, we’ll see that in the jobs. As joblessness falls, the private sector will pick up. Government can then ease off. Mission accomplished! Our real choice is between a large bold program that works quickly – and a slow cautious program that doesn’t seem to work at all.

However, it is disappointing that Galbraith doesn’t follow the logic of his own argument and advocate a Job Guarantee. Given money isn’t a limit (this is a basic principle of MMT) then a minimum liveable wage job offer for all is the most simple program to address the unemployment problem that you can develop.

It is self-selecting – that is, it doesn’t have to be demographically or regionally targetted; it is a fixed wage offer so the the Government would not be competing at market prices for resources; it could start paying wages immediately and therefore stop any further deterioration in the housing market and also would boost private jobs via the multipliers; and falls into his ambition for us of “thinking big”.

The third offering came from Heather Boushey is a senior economist with the Center for American Progress, which while laying claim to being progressive was founded by a former chief of staff to Clinton so you might wonder. Clinton after all was the spearhead for pernicious welfare reform and also ran surpluses that led to the recession in the early 2000s. Arguably, this set the mood for the Americans to elect Bush who wreaked needless havoc around the World.

Boushey asked What the Federal Government Can Do and says that “creating jobs should be America’s No. 1 priority”, I agree so how does she propose this be implemented? It seems she supports funnelling “money into nonprofits and small businesses to create millions of mostly private-sector jobs”. I don’t see this as a progressive agenda at all.

Boushey says to pursue the jobs priority Congress should:

… ensure that the extended unemployment benefits passed in the recovery act do not expire as planned at the end of December. Extending the subsidies to help the unemployed purchase health insurance – or, better yet, allowing states the option to put unemployed workers on Medicaid – must also be done before the end of the year.

Did I read that correctly? The logic appeared to be -> Creating jobs is the No. 1 Priority … and so the government should -> continue paying unemployment benefits. What sort of jobs plan is that? Zero.

If you want jobs to be created the US Government should stop making legislation to faciliate further payments of unemployment support. Rather, just announce that from tomorrow a minimum living wage will be available to anyone who wants it – all you have to do is get down to a depot to register. Then start putting people back to work.

Boushey then says:

Second, the Feds should give states additional funding. State and local governments have shed almost 160,000 jobs over the past year, with nearly 80 percent of the job losses at the local level occurring in the last four months. These layoffs are working against economic recovery at the local level.

All but two states had or still have shortfalls for fiscal year 2010, totaling $190 billion. The aid to states contained in the recovery package was clearly helpful, but it addressed only about 30 to 40 percent of the gap faced by state governments.

While providing untied funding to the states might boost jobs it is not guaranteed. However, in designing an employment guarantee program federal funding should be used but the programs managed and implemented at local levels.

Boushey then says:

And third, the federal government could spur the creation of millions of mostly private-sector jobs by directing additional money into youth and young adult employment (like AmeriCorps, VISTA, YouthBuild and the youth service and conservation corps), child care, after-school programs and in-home health services for the elderly and disabled as well as training for those serving America’s young people, elderly and disabled.

Nonprofit groups and small businesses provide most of these jobs, although they are paid for by programs that are currently being cut by state and local governments. Funneling money into these programs not only quickly gets people into jobs, but supports families and communities by providing much-needed services.

I find this proposal depressing. It is proposing further subsidies to the private sector. Perhaps that is a US-centric matter but in general there are virtually unlimited opportunities for the public sector to take the initiative and use direct job creation to enhance public spaces; to address environmental decay; and to improve personal care support services.

Why would a progressive want this all to underwrite profit-seeking small business behaviour?

The next offering came from William Voegeli is a visiting scholar at Claremont McKenna College’s Salvatori Center and focuses on What the States Can’t Do.

Voegeli says that this crisis has actually damaged “America’s states and localities” more than a usual downturn and the recovery will be an extended one because of the extent of the fiscal crisis at the state level.

He quotes the governor of Indiania who considers “state governments will soon have to choose between a major downsizing or consigning themselves to permanent decline.” So there is little room for the states to provide any stimulus at present.

Voegeli then juxtaposes two “ideological” options:

The liberal answer is that the crisis is an excellent opportunity for the federal government, with its unmatched capacities for raising and borrowing money, to put more funds into the states’ fiscal pipelines, making up for their diminished revenue streams from sales, income and property taxes, and preserving public-sector jobs. The conservative answer is that this crisis makes it imperative to repair leaks in the pipeline, stop those who are siphoning from it, and insist that the ultimate destinations correspond closely to the states’ highest and most defensible priorities.

Isn’t it sad that the “liberal” (read: progressive) position is cast in terms of the deficit-doves, who I argue are not progressive at all because they constrain their thinking by failing to understand the operations of the fiat monetary system. Please read my blog – Debt and deficits again! – for more discussion on deficit doves.

In fact, it is a lay-down misère. The US federal government (and any sovereign government) as Galbraith implies has no funding constraint at all. It can always “afford” to purchase all the idle labour. The question then is not whether it can employ all the unemployed, but in what way it should create the opportunities.

As noted above, the most efficient way of achieving rapid reductions in joblessness and the income poverty that accompanies it is for the national government to make an unconditional job offer at a fixed wage.

I wonder if people would alter their views on policy solutions if they really understood MMT which shows that there is no “financial trade-off” between government spending options when the economy is below full capacity?

I don’t disagree that there is always a need to ensure public allocation is transparent and not rorted. But for conservatives this means contracting out, cutting costs and introducing user pays, which will further undermine the public capacity to create jobs.

When it comes down to it, Voegeli has no jobs solution. He claims that states have to seek these conservative efficiencies, and that:

… any federal “solution” to the states’ fiscal crisis that obviates the need for those kinds of hard choices and essential improvements around the country will not only waste billions of taxpayers’ dollars, but the opportunity posed by this crisis to reestablish fair, frugal and efficient governance.

So you know he is does not have an inkling of the prospects that MMT offers. Remember taxpayers do not fund anything.

As noted, governmental efficiency and transparency is crucial but how we define that is the debatable issue. I do not take a narrow neo-classical view of efficiency which ignores social aspects. Neo-classical (mainstream) economists define efficiency in terms of private costs and benefits.

But mass unemployment is the largest waste of resources that ever occurs and dwarfs the so-called micro-economic ineffiencies which the conservatives become obsessed with. The US would be better off by far if the state and local governments administered jobs programs even if there were some (narrow) “inefficiencies” present. Focusing on cutting costs etc will not produce the jobs that are required.

The next offering came from Dean Baker from the Center for Economic and Policy Research who claims the “The most cost-efficient way to create jobs quickly is a tax credit for employers who reduce work hours, without cutting pay”.

Baker is a self-styled progressive. I have dealt with his proposal in considerable detail in the blog – The enemies from within. His approach is the anathema of a progressive agenda and reflects his ignorance of the way the monetary system operates.

Baker is also a deficit-dove type progressive who thinks that budget deficits are fine as long as you wind them back over the cycle (and offset them with surpluses to average out to zero) and keep the debt ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth.

Deficit-doves worry relentlessly about the public debt to GDP ratio because they assume that the “credibility” of the government debt will be compromised and that this (whatever it means) matters.

They consider there is a limit to the size of the deficit (and public debt) but rarely associate this with the requirement that the government has to match the leakages from the expenditure stream arising from non-government saving. So they fail to admit that by placing artificial limits on the deficits this really means that they cannot guarantee full employment. In that sense, they abandon one of the basic principles of being progressive – a concern that everyone who wants to work can find it.

Proposals that offer tax credits to the private sector fail to understand what causes mass unemployment. The initial reason firms are laying off workers is because they cannot sell the goods and services that are being produced. Employment is a function of aggregate demand. Firms will only employ if there is demand for their output.

So you either have to increase aggregate demand overall or directly create the labour demand in the public sector.

While that appears simple enough, what Baker wants to do is share the burden of deficient aggregate demand between workers.

The same logic underlying the CEPR proposal was used by the French when they brought in a statutory 35-hour working week in February 2000. It was seen as a way of “spreading the work” and reducing their persistently high unemployment rates. The logic is almost identical to Baker’s logic.

However, in France, employers did not hire new workers in any great quantity and unemployment remained largely unchanged (as a consequence of this move). Firms just increased intensity of work and so 5 days work was performed in 4 days. While Baker might claim that to get the subsidy the firm has to shuffle the hours. But what incentive is there for the firms to do that if it not going to sell more goods and services and may add to their labour costs?

Further, Baker’s approach would increase private hiring and adminstrative costs. Workers are not perfect substitutes and so work-sharing can be difficult to organise. There are also spatial (regional) matching issues. So where is the incentive for the employer?

From the supply-side, workers have other commitments/obligations which are not necessarily as flexible (for example, child care arrangements). While flexibility for the worker in terms of hours might seem like a good idea, in many cases it becomes a poisoned chalice if the hours offered to not match these commitments.

Finally, and most important, the proposal is designed to “save” the government money. This is a government that issues the currency. There is also no inflation problem in the US at present. As a consequence the US government needs to spend much more in net terms.

The final offering Lessons From the W.P.A. came from Nick Taylor who recently wrote “American-Made: The Enduring Legacy of the W.P.A.”

I really liked Taylor’s opening:

The New Deal’s Works Progress Administration was the original welfare-to-work program. It took 90 percent of its workers from relief rolls. It cost more than just handing out relief checks, but the idea was to use the unemployment crisis of the Great Depression to improve the infrastructure, stimulate the economy and retain workers’ job skills.

In this neo-liberal era, welfare-to-work means the introduction of pernicious work tests and rules that deny the most disadvantaged workers access to essential income support. And while punishing the unemployed for what is a systemic failure to produce enough jobs, the Government abandons it responsibility to provide these jobs.

In the 1930s, welfare-to-work meant that the government offered jobs so that people could come off the relief.

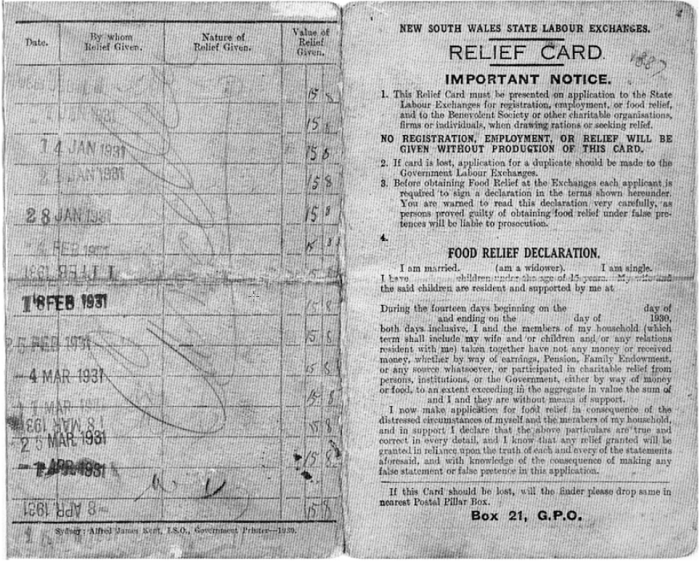

As an interesting aside, the following photo is of a NSW government relief card in the 1920s. By 1932, around 30 per cent of Australian workers and families were relying on direct public relief (and private charity). All but South Australia then brought in direct job creation programs which were strongly subscribed and produced many lasting pieces of infrastructure, some of which are still providing benefits today. At the end of this blog are some photos from that era that might also be of interest.

However, Taylor then asks whether the W.P.A. is suitable now. He says:

Laborers were a higher percentage of the work force than they are today, and the majority of projects were in construction … The W.P.A. was inefficient on purpose in its construction work. Project budgets were spent largely on labor. Machinery, materials and administration took a back seat. It would be hard to argue in today’s economic climate that jobs, as badly needed as they are, should be created with no thought for efficiency.

So once again we encounter the “efficiency” argument. This is a common argument about Job Guarantee schemes and relates to the quality of the jobs. It is often asserted that the JG workers would usually be paid more than they produce which implies that the output they produce is not valued by the economy.

Indeed, the criticism that JG jobs are not “real jobs” carries with it the related claim that the output produced is not “real output”.

How should we assess this claim?

First, it suggests that the only mechanism that can validate output as being of value is the private market (which includes government spending that competes in the private market for resources). Even neoclassical theory acknowledges that private benefits and costs can diverge from social benefits and costs.

Many activities which produce outputs are possible which have zero private market value but deliver positive contributions to the community (positive social value). The JG would likely focus on labour intensive activities which would fall into this category.

It is also obvious that many jobs are created in the private sector, especially in the low skill service sector (for example, fast food shops) which may have very little or even negative social value. In assessing social value, we also have to consider the impacts on the previously unemployed individual who transits from welfare dependence via the JG. There is substantial evidence that these benefits are likely to be significant.

In a paper I did with Randy Wray in the Journal of Economic Issues (2005) we wrote (page 241) that:

… it is difficult to believe that ELR will produce less social value than fast food production.

Second, there is a problem that economists have to confront relating to the static concepts of work and productivity which underpin the criticism that JG jobs are not productive. To accommodate the benefits of technological progress, a debate about the future of paid work is clearly important.

The concept of gainful work which relates to performing work for profit will have to be broadened to embrace a range of other activities not usually considered to be work. We clearly will need to make a transition in the way we link work and income generation such that old-style capitalist concepts of the work ethic are replaced with more creative uses of human activity.

Further the right to work and hence income has to be preserved for all. In advocating a transition, I do not support those who advocate for institutionalising non-work via a basic income guarantee.

I do not consider that society is advanced enough as yet to embrace a culture whereby some do not work at all but receive State support without commensurate activity being required. Social attitudes take time to evolve and are best reinforced by changes in the educational system.

In this context, the JG is a progressive, forward-looking approach for a state aiming to rebuild communities based on the purposeful nature of work that can extend beyond the creation of surplus value for the capitalist employer.

It also provides the framework whereby the concept of work itself can be extended and broadened to include activities that we would dismiss as being leisure using the current ideology and persuasions, as well as to encourage private sector activities currently counted as productive in a narrow sense that societies of the future will view as socially destructive.

So I always argue there is a need to extend our concept of productivity beyond the narrow conceptions provided in mainstream economics.

For example, what value – in terms of intergenerational benefits – do we place on children seeing their parent(s) go out to work each day as opposed to being idle and alienated? There is productivity (and efficiency) in just providing jobs.

Taylor continues:

Furthermore, it’s incorrect to think that the federal government created the jobs the W.P.A. provided. Almost all the projects financed by the W.P.A. bubbled up from states and local governments. These ranged from road and bridge work to teaching and other white-collar jobs. Federal agencies, especially the military branches, also vied for W.P.A. funding but they went through the same vetting process as the others. The only W.P.A. jobs specifically created by federal government were in the four arts projects, a tiny percentage of both jobs and spending.

Okay, fund it at the federal level where there is no revenue constraint and implement it as the local level where unmet need can be better assessed.

Taylor finishes by saying that:

A W.P.A.-like thrust today would demand a close eye on value and a scorched-earth policy toward useless earmarks. But today’s skill sets among the unemployed provide the chance to make long-lasting gains in our infrastructure and even our culture if things are handled right.

I am still unsure what he is advocating. His book is clearly sympathetic to the New Deal jobs programs.

Conclusion

Once again I find it disappointing that this debate didn’t include the views of researchers that have international prominence and have spent years developing proposals that are exactly designed to meet the challenge they are debating.

The offerings that seem to support some direct jobs action in this debate are unclear and seem to fall short of what is required. The other proposals will not provide answers to the employment problems.

Photos from the Great Depression – Australia

Another terrific post. I especially enjoyed your discussion of what is considered productive, and the need to develop a broader conception of productiveness over time. The post also clarified for me your thinking behind the preference for a job guarantee rather than an income guarantee. Now that I understand your reasoning, I think it makes a lot of sense. 🙂

In internet discussions, I have come across the objection that employment-guarantee jobs are not productive. The objection never made sense to me because productivity is socially constructed. Markets are just one way for society to construct productivity, but in many respects not a good way, and certainly not the best way in all cases.

Great article

Listening to the folks who derisively maintain that public sector people arent “working” or that the govt cant “produce” anything is becoming quite irritating. This is a pervasive view over here in the old U S of A.

Just once, when a “business” type is questioned about our employment situation and spouts the need for more small businesses (the lifeblood of America) as the only “real” solution to unemployment, I want to hear a media person ask; “Sir, if every unemployed person were to start a small business tomorrow, how many would still be employed in a year?” Statistics show that less then 20% of small businesses last a year, yet these nimrods want to act like a govt jobs program which might only employ someone for 2 yrs is somehow inferior!? Gimme a break

Great post, Bill!

Alienated . . . good points.

FYI . . whenever the “productivity” issue arises, I always ask “how productive are the unemployed?” Even within the more neoclassical paradigm, the appropriate comparison for productivity of JG workers is against that of the unemployed, since that’s what they’d be if they weren’t in the JG. Or, using Bill’s approach, how much social value does unemployment provide? As we know, unemployment, if anything, decreases productivity, given skills decline while virtually every socioeconomic problem (divorce, crime, etc.) is exacerbated to some degree by unemployment. I have very little doubt that a decently constructed JG program (including traning, etc.) would add to national productivity and create value, but regardless the bar is set very, very low by the alternative policy approach of sustainaing unemployment.

Best,

Scott

Great post.

Any chance of a post on Greece?

The question is whether they should ditch the euro and return to their own sovereign currency?

Is this doable? Because if it isn’t, then all the participants in the EU stand to be systematically raped by the IMF, right???

Any remedies?

Re states in the US laying off 160,000 workers during 2009: PATHETIC ! The US would be better off with Laurel and Hardy in charge (though Bill Mitchell would be even better).

It seems like you’re suggesting some sort of WPA style public works program to be implemented by the various world gov’ts.

While that’s preferable to simply paying people not to work, unless the jobs that gov’t provides actually *increase* the overall productivity of a country, then they aren’t going to help long term (maintaining infrastructure isn’t a stimulus, as it protects current productivity w/o improving it).

If said public works program was for major infrastructure improvements new hydro/solar/nuclear plants (and retrofitting existing plants), or a better high-speed fiber optic system (the USA lags Europe in this respect) then it might help.

But since the cause of this was an unstable monetary system (banks are historically incapable of acting responsibly, and gov’t is feckless in resisting them), perhaps we should consider striking at the root instead of the branches.

What about a negative incomes tax as a floor? It has a favorable history in the US on both left and right. A big problem with a JG in the US is political. It is associated with FDR’s New Deal, a cuss word for the right. However, there is impressive historical support for a negative income tax on the right as well as the left. A compromise might be more feasible politically with this approach, while the fight over a JG would be fierce.

“Economists of the stature of John Kenneth Galbraith (The Affluent Society), Robert Theobald (The Guaranteed Income), and Milton Friedman were major pro-basic income participants in the debate that flourished during the 1950s and 1960s. The Triple Revolution movement, a Ford Foundation effort, enlisted enormous intellectual support for basic income during the 1970s as the simplest solution to all the problems that money can solve. In 1966 even the U.S. Chamber of Commerce was willing to sponsor a national symposium on guaranteed income. Political leaders left, right, and center agreed that our society was rich enough to abolish poverty; they differed only on the means of doing it. Liberals favored a congeries of government programs like Social Security; conservatives like Barry Goldwater preferred a negative income tax that needed no costly bureaucratic supervision.

“The idea of a guaranteed annual income underlay Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Johnson, swamped by Vietnam, wasn’t bold enough to carry through. But guess whose words these are? “I [have] proposed that for the first time in America’s history we establish a floor under the income of every American family with children. We called it the Family Assistance Plan.” That’s Richard Nixon speaking in 1970 about his 1969 proposal to “lift people out of poverty … to restore pride and dignity and self-respect.” Like LBJ’s program, Nixon’s vision was a casualty of the partisan bitterness of Vietnam-era politics.

“What has survived from that era is Bill Clinton’s Earned Income Credit, a variation on Friedman’s negative income tax. The IRS now sends a supplementary income to families that earn below poverty level. As of 1997, the most recent high-level brainstorming on the subject took place at the Aspen Institute Domestic Strategy Group where the Harvard economist David Ellwood proposed using the Earned Tax Credit as a way of distributing money to the poor….”

http://www.earthlight.org/essay44_roszak.html

I don’t seem much hope for either a JG or a NIT politically in the present highly divisive environment in the US, unless the leadership and public were first educated about MMT. This is a daunting task, when even established figures like Jamie Galbraith apparently think MMT is unrealistic to even broach in light of the established (pre-1971) narrative. So far, just about no one is talking about MMT other than at the margin, and even the vast majority progressives remain under the spell of the established narrative and its outdated and now erroneous memes, which works against their arguments based on principle.

Thanks Bill!

For me, I often ask: what is this earth; who are we? One tiny little jewel of a planet 2/3rds out along the trailing arm of one of millions of spiral nebulae – rotating grandly by indeterminable laws, in infinite time and space. 6.7 billion of us coming and going – without a trace!

Oh yes – not another tree around for light years; no food supply, water supply, air supply, temperature just right for us. We come to this beautiful planet and turn it into a factory, or a war zone. We harm our own kind when there is nobody else that could take care. Let’s face it – we are THE problem: the primary cause of every other problem. Solving this problem is the search!

I believe finding your own humanity first, so that when you see another human being you see another human being is a good place to start.

Every conference would benefit from such an affirmation – and commitment. I see a difference between what I would call true intelligence, and mere intellect subservient to selfishness and concepts for their own sake. People who harm others through their selfishness deserve to be stood naked in the sun! People who truly help deserve our gratitude – not some idiot who thinks that a man can be measured in money or position. We are such conditioned creatures ….. not so bright: look at how long it took to work out where the rain came from? – a flat earth? – humanity and the earth concentric to the passage of the sun? Ay-ay-ay!!

And we think we are quietly superior to the ‘DreamTime’ of our humble indigenous brothers?

Cheers ..

Greg, I haven’t checked the figure recently, but in the 80’s, “small business” in the US meant firms with gross revenue under 50 million a year. This isn’t exactly mom and pop shops. But the problem is that the playing field is tilted toward really, really Big Business, to the disadvantage of not only workers but also “small” businesses.

Hi Bill.

Again, a great post! I think I’ve understood the basic economic principles and Scott Fullwiler also summed them up very nicely and I also like the way it aims at building from the bottom up as opposed to throwing money in from the top. Indeed I think we need a reassessment of our perception of productivity away from those who profit from gambling with the livelihoods of others. Two question, if I may: How would your proposals look like for the highly skilled unemployed? If you had say an unemployed engineer or lawyer, what options would you offer him/her under your JG proposal? And concerning France: apart from the fact that reducing working hours didn’t create any new jobs (if that’s the benchmark, then I guess it failed), do you have any other objections? If I manage to squeeze more or less the same amount of work out of 34 hours as out of 42 hours, this leaves me with more time to take care of my children, prepare and eat good food, visit relatives and friends, read a book or whatever. Personally I would consider it a gain in quality of life and I don’t see any negative implications for society other than the missed possibility to squeeze out even more work, which the French obviously chose not to do. ‘Yay for France!’, I would say.

Regards, Oliver

bill, you may be interested in this article by James Purnell (former Labour work and pensions minister )

http://www.openleft.co.uk/2009/12/04/jobs-guarantee/

Mr Hickey

I was unaware of the exact cut off for being considered small business so thanks. Obviously many of these small businesses could expand and hire under the right conditions but there is no way they alone can solve the employment issue. They are also the first ones to have to lay off since every lost customer/account is crucial to their bottom line.

You are right about the playing field being tilted towards big business and for many small business guys the opportunity to be bought out is a lottery winning scenario. Big business buying you out almost always is a net job loss.

Thanks scepticus

appreciated

bill

Oliver: “Yea for France“ indeed. While not resolving insufficient aggregate demand problems, the 35 hour week was popular there for the quality of life reasons you list.