I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

One should become more radical as one grows older

In a sea of conservative media, two articles stood out this weekend which captures a debate that should be raging but will be quickly buried under the re-emerging neo-liberal hubris unless significant new alliances are formed. In recent weeks, as different economies are showing some signs of recovery, some key players within mainstream economics have been coming out in defence of the profession. They have been accusing critics of misunderstanding what economics is all about and saying that economists have actually saved the world. I covered some of this sort of positioning in Friday’s blog. In this blog I continue that theme but from a different angle. The conclusion is that if we want real change then “one should become more radical as one grows older”. We will see what that means as we go.

In the Sydney Morning Herald yesterday (January 02, 2010) regular Guardian writer Larry Elliot wrote that the Old guard will defend their position to the last and said that:

Investment bankers. Subprime mortgage brokers. Ratings agencies. Central bankers. All of them are in the rogues gallery of villains responsible for the deepest crisis in the global economy since the guns fell silent at the end of the Second World War.

Yet the group that really screwed up in the noughties was the economics profession. For the dismal science, the events of the past 2½ years have truly been an existential crisis.

This, after all, was a crisis that economists said couldn’t happen. Not wouldn’t, couldn’t. This was an era when all the big macro-economic problems were supposed to have been solved. This was a decade that saw the ultimate triumph of mathematical, model-based economics not just in the classrooms of Cambridge and Chicago but in the dealing rooms of London’s and New York.

I note that it was only some of the economics profession – the dominant camp and the overwhelming majority to be sure – but not all. All the things that are now being said about the failure of my profession (the mainstream camp) were often said by those of us in the modern monetary theory (MMT) camp in the last 20 years or more.

We intensified our attacks in the 1990s when it became obvious that a crisis was approaching. The signals – governments increasingly running budget surpluses and the private sector increasingly maintaining their spending by rising indebtedness. The two signals were extolled by the mainstream as the virtues of an expanding self-regulating financial sector offering real choices to individuals to build wealth.

The surpluses were represented by the mainstream as the exemplar of prudent fiscal management – leaving room for monetary policy to take over the reins of counter-stabilisation policy and fight inflation. This was the recipe that the mainstream considered to be optimal.

Elliot notes that:

Those who argued that global finance was heading for a big fall were slapped down. How could that be when markets were efficient? Those who said the boom in US house prices would be followed by a bust were told in no uncertain terms that the market never lied: prices reflected every piece of available information about the past, present and future.

His conclusion: “… it was all bunk. The mathematical models blew up … Human nature intervened …” And that human behaviour was irrational and prone to herd-like decision-making – that is, not remotely like the behaviour assumed by the mainstream models.

Elliot notes that Chicago economist “Robert Lucas, the high priest of uber-rational markets” had bragged in 1980 that governments could not manage economies only markets can. I have written about the reasons why no one should listen to Lucas in previous blogs – Islands in the sun and Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not!.

In a debate last year (July 18, 2009) in The Economist (you have to pay for the content), Lucas, arrogant to the end, rejected criticism that the financial crisis was a failure of mainstream macroeconomics. He said:

THERE is widespread disappointment with economists now because we did not forecast or prevent the financial crisis of 2008. The Economist’s articles of July 18th on the state of economics were an interesting attempt to take stock of two fields, macroeconomics and financial economics, but both pieces were dominated by the views of people who have seized on the crisis as an opportunity to restate criticisms they had voiced long before 2008. Macroeconomists in particular were caricatured as a lost generation educated in the use of valueless, even harmful, mathematical models, an education that made them incapable of conducting sensible economic policy. I think this caricature is nonsense and of no value …

One thing we are not going to have, now or ever, is a set of models that forecasts sudden falls in the value of financial assets, like the declines that followed the failure of Lehman Brothers in September. This is nothing new.

But of-course this is not the criticism that MMT made. It was clearly not possible to predict the exact day that a major failure would occur but it was possible to highlight the “tendency for a crash” that was building and to document why each year we were getting closer to a crash at this time.

The mainstream models and approaches were not in a position to assess the dangers that were building. They were in denial of the risks that were building as the governments went into surplus and the private sector went increasingly into debt. The mainstream retorted when I raised this at conferences – “you are ignoring the wealth” – “the government is boosting savings” – “Yada yada yada blah blah blah”. Events have proven them to be very wrong although very few of them will be enduring the costs right now.

If you go back to the late 1970s as macroeconomics was jettisoning its Keynesian origins and instead creating the monster that the modern approach has become, Lucas wrote a self-congratulatory article with Thomas Sargent – After Keynesian Macroeconomics. The article is somewhat technical but most people could read some of it. On page 6 you read:

For policy, the central fact is that Keynesian policy recommendations have no sounder basis, in a scientific sense, than recommendations of non-Keynesian economists, or for that matter, noneconomists. To note one consequence of the wide recognition of this, the current wage of protectionist sentiment directed at “saving Jobs” would have been answered ten years ago with the Keynesian counterargument that fiscal policy can achieve the same end, but more efficiently. Today, of course, no one would take this response seriously, so it is not offered.

The article then continued to outline the more prospective developments in “equilibrium business cycle theory” which “imposed by it insistence on adherence to the two postulates (a) that markets clear and (b) that agents act in their own self-interest” a so-called rigour that was missing in previous (Keynesian) approaches.

This is the so-called development of microfoundations that the mainstream pat themselves on the back about which essentially renders their macroeconomics void of meaning. Combined with the assertion that individual decision-makers have rational expectations, that is, on average, they know the true model generating economic outcomes but make mistakes (which average to zero), Lucas and Sargent claimed this was the way forward for macroeconomics.

Soon after in 1980s, Lucas wrote an article in Issues and Ideas (Winter edition) called the The death of Keynesian economics. There you read his now-famous and boastful quote:

… one cannot find good under-forty economists who identify themselves or their work as Keynesian. Indeed, people often take offence if referred to as Keynesians. At research seminars, people don’t take Keynesian theorising seriously any more; the audience starts to whisper and giggle at one another.

I had just started my postgraduate studies in economics at that point and prior to doing a PhD I studied in the Masters program at the extremely right-wing Economics Department at Monash University. It was full of those who promoted the ideas that Lucas and Sargent and others were pushing out.

The atmosphere at the time towards dissenters … as you might pick up in the previous quote … was hostile and intolerant. Laughter was a way of putting young students down who dared to think. It either destroyed the student’s curiosity and moulded them into “the program” or it just strengthened their resolve (as in my case – but I was in a minority of about 1 or 2 in my year). It was a bullying, arrogant atmosphere. I was continually being called a “pop sociologist”.

The advantage for me was that it gave me an incentive to know their (stupid) stuff as well or better than most of them but also develop other understandings that have become my current work and position. A better education all round I think.

Elliot says in relation to Lucas’ “bragging in 1980 that … people don’t take Keynesian theorising seriously any more” that:

They do now. As governments around the world acted in unison to prevent the collapse of the entire global banking system, recapitalising banks, slashing interest rates, boosting government spending, printing money, what was Lucas’s response? “In a foxhole, we are all Keynesians.”

This theme had earlier been considered (October 23, 2008) by Justin Fox in the Time Magazine article The Comeback Keynes. In that article, he says that staring at the collapse of the World economy:

… governments seemingly cannot help turning to the remedy formulated by Keynes during the dark years of the early 1930s: stimulating demand by spending much more than they take in, preferably but not necessarily on useful public works like highways and schools. “I guess everyone is a Keynesian in a foxhole,” jokes Robert Lucas, a University of Chicago economist who won a Nobel Prize in 1995 for theories that criticized Keynes.

Remember Lucas and his cronies have a body of work that students are indoctrinated with that says that government monetary and fiscal policy should have no effect on the real economy once it is fully anticipated. Some of the extremists even denied the “outs” that were provided – via totally ad hoc “short-run” effects that were allowed under certain conditions. But overall these exceptions were considered to be trifling and gave no cause for governments to actually try to manage the economy.

Fox later reported that in an E-mail exchange with Lucas he said this:

Well I guess everyone is a Keynesian in a foxhole, but I don’t think we are there yet. Explicitly temporary tax cuts do nothing: people just bank them. Supply side tax cuts are fine with me, but they take time to work and at some point we need the revenue to run the government.

I feel the current situation requires a lender of last resort but not a fine tuner.

Elliot says that despite the evidence to the contrary the “signs are that the old guard will not give up without a fight” … that “rather like old communists talking about the Soviet Union after the Berlin Wall came down, that the market did not fail: it was just that governments prevented market forces from working properly.”

He juxtaposes this with the view that others now realise that “the intellectual failure of the past 30 months has shaken the profession to its very foundations”.

The other interesting article I read over the weekend was published in the Guardian on January 1, 2010 and written by Costas Douzinas. The article – In the next decade, I hope to become more radical proposed that:

The left is the main hope against xenophobic, securitised, apocalyptic barbarism. We should expect radical change

Not many people these days are willing to identify with the left. Even the deficit-dove “Keynesians” (like Krugman) are still essentially pro-market neo-liberals with a “conscience” and do not advocate widesweeping reforms of financial markets and on-going deficits. They almost fall into Lucas’s foxhole.

I liken it to the quote after the Second World War that you couldn’t find too many Nazis in Germany anymore”. Sure enough the mainstream profession, apart from the marginalised Austrian enclave and some more rabid new classical real business cycle theorists have all indicated a need to save capitalism from itself – for the time being. But none are advocating the type of changes that Douzinas outlines.

It is an interesting retrospective. He says:

The end of the 20th century was … exuberant. President Bush Sr triumphantly announced in 1991 that a “new world order” was coming into view … Globalisation, neoliberal economics and humanitarian cosmopolitanism were the contours of the new age … Globalisation went hand in hand with the rise of neoliberal capitalism. The WTO and IMF imposed globally a model euphemistically known as the Washington consensus: pressure was put on developing states to deregulate and open their financial sector, privatise utilities and reduce welfare spending. These policies would, it was argued, unleash the economic potential of the developing world, hitherto blocked by inefficiency, corruption and socialism.

Apart from ugly diversions like “Iraq and Afghanistan”, Douzinas proposes that the new era guaranteed a new cosmopolitanism, which promised “a morally guided legal and institutional framework, the weakening if not abolition of the state form, and the strengthening of international institutions and civil society.”

Douzinas is honest enough to admit that the rhetoric was even “accepted by people on the liberal left, like me.” In effect the left-program was over and the left could concentrate on advancing “multiculturalism” instead of advocating “radical change” and “membership of Amnesty” would replace membership “of political organisations”.

That is a familiar tale for many I am sure. In Australia we were told that with families being cajoled into buying share offerings in the privatised telecommunications company that “everyone are capitalists now” and the old left-right discourse was a thing of the past and the worker-capitalist distinction was dead in the water.

I remember giving a keynote speech at a conference in Sydney in about 2004 about the impending savage changes to industrial relations laws that the then conservative federal government were soon to introduce. I made obvious points about the damage to the rights of workers and their standards of living (the empirical evidence now available after they succeeded in introducing the legislation is that I was correct in my forecasts).

The speaker who followed me was about 24 years of age and young entrepreneur of the year or something like that. She proclaimed that her generation no longer thought in those terms (that I had outlined – worker and boss) that none of them were workers who “went to work”. Rather she represented them all as being entrepreneurs continually seeking opportunities to profit even if the majority of her cohort were working in precarious casualised jobs on low pay “flipping lentil burgers”.

The rhetoric that was around however had dressed this secondary labour market existence up as entrepreneurial venturing. Total nonsense of-course but that was the era and the nomenclature that evolved to cover up what was really happening as the financial markets headed for the bust a few years later.

Douzinas declares that “at the end of the first decade of the millennium, every aspect of this fantasy has been reversed. If this was a new world order, it was the shortest in history” and he outlines some “recent signs of this “bonfire of falsities””. He talks about the fiascos in Iraq and Afghanistan and the myth that torture was confined to evil regimes. That is not really my professional bailiwick although I agreed with his sentiments.

Another falsity is:

The promise that market-led growth based on unregulated foreign investment and fiscal austerity would inexorably lead the global South to western economic standards has come to be seen as the greatest deception of our times. The gap between the North and the South, and between rich and poor, has never been greater … The beginning of the end of neoliberal idolatry can be timed accurately: 15 September 2008 and the demise of Lehman Brothers. Greedy banks, conniving governments and economic “science”, the witch medicine of our age, are still in mourning but reality has caught up with their convenient fantasies.

I reflected on the widening gap between rich and poor nations in this blog – IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries. The fact that the low income nations have not enjoyed per capita income growth but seen their resource-bases plundered by advanced nations is the starkest of indictments of the mainstream economics myth (propagated in this context by the IMF and the World Bank). And that trend was obvious long before the current crisis had brought the advanced economies to their knees.

Douzinas also notes that:

The former socialist countries moved fast from command economies to klepto-capitalism and from state oppression to market decadence without passing through a humane social and political order. The western panacea has been found inappropriate for many people at the heart of Europe.

When the Berlin Wall fell the neo-liberals were overjoyed. Capitalism was becoming the natural order. As I have mentioned in the past it is now 20 odd years on and the former socialist nations that I am familiar with (as a consequent of my work with the Asian Development Bank in Central Asia) are not glowing testimony of the benefits of capitalism.

In many cases life now is very tough. This is particularly the case for older people who worked all their lives in guaranteed jobs and had modest but comfortable lives but who have had their pensions denied by the new order and are forced to pay “market” rates for their accommodation. For them the collapse of “socialism” was a fast train to poverty and indignity not withstanding the fact that we extol their “freedom”.

There is also a new class of criminals in these nations – some close to government – who share the booty that was more evenly spread in the past. Those who care are realising that the youth in these nations – who are systematically denied employment opportunities (that their parents enjoyed under the state system) – are falling by the wayside into substance abuse, petty crime and fundamentalism. None of this is pretty at all.

Douzinas cites the current situation in Europe as another sign of the failure of the “new order”:

Old Europe, the willing minor partner in the cosmopolitan plans, has become seriously ill. Liberalism and social democracy, the proud social models it created, have atrophied as they converged towards the economics and politics of neoliberalism. The European Union has been emptied of political imagination and institutional will … The current travails of Greece, Spain and Ireland are further evidence. The downgrading of Greece’s credit rating by three unaccountable private companies which follow neoliberal orthodoxy is leading to externally imposed austerity, serious deterioration of living conditions and social unrest. These were the companies giving Lehman Brothers a top rating just before its collapse.

I have written extensively about the lunacy of the Euro monetary system. Why the citizens in these nations voted to straitjacket their governments is an on-going research question. It was always clear – by the nature of the structure of their monetary system (divorce between the fiscal and monetary sovereignty) that the system would not cope in a major economic crisis such as now.

I also concur with Douzinas anger that the corrupt credit rating agencies should be held accountable for their past deeds and stopped from continuing to cause “austerity, serious deterioration of living conditions and social unrest”. I consider dealing with those firms to be one of the urgent reforms necessary to improve the functioning of the world financial system.

I also consider the combination of neo-liberalism and fixed exchange rates (with a non-accountable central bank) to be the most potent mix of economic dysfunction that we could contrive. The Old Europe is certainly sick and only the disbanding of the monetary union and its anti-social and anti-job treaty obligations (for example, the Stability and Growth Pact) will ensure it survives.

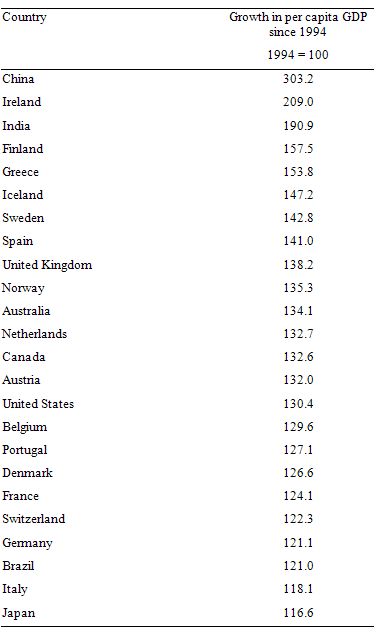

I did some empirical analysis today to check out how the pre-crisis years had worked for Eurozone countries relative to others. I used GDP per capita as a measure and converted it into an index number with the base year being 1994 when the countries started preparing for entry in to the community. The data used was the IMF World Economic Outlook Database as at October 2009.

The following Table is interesting and shows the index number at 2007. So you can compare it to the base year 1994 = 100. It shows non-Euro nations among the fastest growing (China and India).

China stands out having grown by 3 times in the period shown. I noted a commentator yesterday claim that this was a reflection of their low wages and showed that neo-classical labour markets do work (by sourcing the lowest cost labour). However, the major driver of growth in China has been the massive state-led deficit spending. The rapid growth in “public” infrastructure has made it possible for capitalist firms from abroad to locate there. These firms also enjoy substantial state subsidies to entice them to set up there.

But what caught my eye (and was to some extent a bit unexpected – in relative magnitudes) was the fast growth in GDP per capita since 1994 of Ireland, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Sweden, and Spain. The economies of most of these countries were fuelled by rapid construction booms and debt-driven consumption binges. They are now among the worst performing of the advanced nations relying on massive state intervention to survive but running foul of the ridiculous Eurozone fiscal constraints.

Douzinas then turns to a hopeful tack. He considers that while “the response of governments to the end of the neoliberal hegemony is still timid and uncertain”:

… people around the world have started reacting, as strikes in France, Greece and India, the Latin American popular movements and the reaction of youth to ecological catastrophe indicate … The 21st century brings the age of western empires and cosmopolitanisms to closure.

The left is the main hope against an endgame of xenophobic, securitised, apocalyptic barbarism. But this is not the New Labour or German SPD nominal “left” nor that of departed “communism”. New forms of socialism, new types of political subjectivity and solidarity are emerging in Latin America, in the ecological movement and in the ghettoes of our great cities. What the decade taught me was to expect radical change and to try to imagine a renewed socialism in which freedom cannot flourish without equality and equality does not exist without freedom. The new decade’s resolution: one should become more radical as one grows older alongside the 21st century.

I really like his new year’s resolution and I might adopt it myself even though it is already January 3. Three days of being less radical shouldn’t matter too much!

But thinking about his vision is very exciting and challenging. The young who have been hit badly by the global recession have finally learned that business cycles exist.

I have sensed that they are leading a new form of protest, particularly related to urban life and environmental politics. The problem I sense though is that they do not have a well articulated economic understanding sufficient to challenge the neo-liberal order.

As Elliot says, the mainstream is not about to resign their sinecures and say sorry. They are religious zealots who think the facts get in the way of their theory. They will continue to dismiss any challengers who are ill-prepared.

In that sense, I think MMT represents the framework that the new left that Douzinas is seeing emerging should take up because the mainstream economists cannot debate against it with any sense of authority. They certainly dismiss it. But when cornered they look like fools.

This raises another issue that I often get challenged about. Is MMT left-wing dogma?

The answer is very simple. Clearly not. Much of what I write about is based on an understanding of how the modern monetary system operates.

Basic principles of the national accounting relationships which underpin modern monetary theory are not matters of opinion (values). These include (but the list is not exhaustive):

- That a government deficit (surplus ) will be exactly equal ($-for-$) to a non-government surplus (deficit).

- That a deficiency of spending overall relative to full capacity output will cause output to contract and employment to fall.

- That government net spending funds the private desire to save while at the same ensuring output levels are high.

- That a national government which issues its own currency is not revenue-constrained in its own spending, irrespective of the voluntary (political) arrangements it puts in place which may constrain it in spending in any number of ways.

- That public debt issuance of a sovereign government is about interest-rate maintenance and has nothing to do with “funding” net government spending.

- That a sovereign government can buy whatever is for sale at any time but should only net spend up to the desire by the non-government sector to save otherwise nominal spending will outstrip the real capacity of the economy to respond in quantity terms and inflation will result.

These concepts and understandings of modern monetary theory don’t impose any political opinion at all about how the state might use these opportunities. There is nothing intrinsically left-wing or right-wing about these statements.

The concepts are technical understandings of how a fiat monetary system operates. Most of us live in economies like that. Modern monetary theory is different from Keynesian macroeconomics and neo-classical macroeconomics in the sense that it begins at the operational level. The knowledge framework that has been built up by modern monetary theorists did not start with some (untestable) a priori assumptions – that is, the deductive approach that exemplifies the macroeconomics that you read in mainstream textbooks.

Modern monetary theory starts with how the system works not how we assume or want it to work. On top of that a some basic theoretical insights from Kalecki, Keynes and others relating to uncertainty, investment dynamics and aggregate spending are added to the operational insights to form a coherent macroeconomics. It is a macroeconomic theory that is complete and holds up very well in explaining the revealed dynamics of fiat monetary economies.

So adding theoretical propositions like “mass unemployment ultimately occurs when net public spending is insufficient” to the stock-flow, national accounting principles – is also neither left nor right thinking. It reflects the behavioural extensions of the way the government sector impacts on the non-government sector.

You could say the whole concept of money or employment or whatever is ideological and if you do then you are using the terminology in a way that will not get us very far. Sort of like the arguments we had in first-year philosophy to make ourselves feel as if we were deep. For example, to prove how abstract we were we might ask the question – How do I know you exist? These days my answer is “You don’t! Get over it.”

But in any functional sense these principles and the core considerations of MMT are non-ideological – they are neither left nor right.

It is clear that voters might push a national Government (like in Britain) into cutting back spending much earlier than they should – when assessed from a modern monetary perspective which says that if the non-government sector desires to net save then aggregate demand must be supported by the government sector for output and employment levels to remain high.

If that occurs, then MMT will be a sound guide to what will happen in terms of the measured aggregates. Cutting back to early will cause further income and output losses and the budget deficit will rise. That situation will arise as a result of the understanding that MMT provides.

In general the neo-liberal period has been marked by a failure to understand these principles and to disregard warning signs that were easily interpreted by someone who did understand MMT. The mainstream profession simply does not have the tools available to understand these things.

You should always ask a neo-liberal to provide a coherent explanation of the evolution of the Japanese economy since 1990 using the principles laid out in their macroeconomic text books. Ask them to explain the years of high deficits, high public debt issuance, zero interest rates and deflation. The reality is that they cannot explain these relationships in any meaningful and consistent manner!

So in that context, you have to separate the operational understanding that MMT provides which is superior in insight to the mainstream approaches to macroeconomics – from political statements that, MMT advocates might make from time to time.

An understanding of MMT does not immmediately make you a left-winger. You could easily understand the body of theory yet eschew some of the policy proposals that have emerged.

For example, while I think it is ridiculous for national governments to run surpluses when there is unemployment, a person with a different value system might value the decrease in the net public position more highly than the massive unemployment.

They might consider that unemployment was a more functional way to ensure high profits (via wage discipline) than full employment. So the person would understand what will happen if the government uses contractionary fiscal policy but has a political preference for that state of affairs.

Whereas I say that I value people having work with an environmentally sustainable world above most other things and so my understanding of how the economy works tells me that the only way I can achieve those political (or ideological) aspirations (full employment) is for the government to run deficits up to the level justified by non-government saving.

But a left-wing campaign that Douzinas envisages has to be able to run a coherent economic debate which shows that it is non-controversial for governments to run continuous deficits under certain economic conditions. The radical groups will never make progress in any widespread way until they can attack the neo-liberals on their own turf – the economics debate.

The reality is that the conservatives are very weak in this context. Their theories – so arrogantly pushed on us over the last 30 years or so are in tatters. They will try to reassert them in various ways but at present they are vulnerable.

The radical attack dogs should seize their moment. I think that Douzinas’ resolution should become shared by all of us who want change and better equity outcomes.

Digression: more diversity

While on the topic of different views filtering out, it was also interesting to read that the new Corus chief urges UK to invest in infrastructure. The report dated December 27, 2009 said that:

Britain should shrug off worries about its huge government deficit and prepare to spend “tens of billions of pounds” on infrastructure investment to push the economy out of recession, according to one of the UK’s leading industrialists.

The report said that “the new investment programme he was advocating would put cash into projects such as railways, schools, roads, hospitals and other amenities … Spending on capital schemes such as these also has a big impact on the economy because so many of the companies that work on the projects are local.”

It also noted that the rising borrowing was not something to worry about at this point and it “with the economy still stuck in recession it was premature to start reducing the UK’s stimulus programme”.

So that is a new voice.

And that is enough for today.

Wow Bill,

What a great start to the new year with this post. This should really concern you (although I feel quite emboldened by it!) but these are the exact types of things I have been pondering of late. Usually you are hitting on what I am thinking.

Since I discovered MMT, about 8-10 weeks ago, I’ve always felt that the non ideological nature of it is its strength and you do a wonderful job of pointing out the basic operational truths which CANNOT be argued about.

I have no trouble being a radical and I have found myself becoming more radical as I age. Most of my right-wing work cohorts have chided me for not being more mellow as I get older. For me its a matter of being more and more curious about the nature of things and when I start to learn about the “deceptions” in our common knowledge base I want to loudly point them out. This is not to say that I think all the deceptions are born of ill intent (though some clearly are) I simply think it is out of intellectual laziness that most of us accept what our experts have told us. Its much “easier” that way. Going against the flow is hard.

I am hoping that Warren Mosler can get far enough in the American political process to at least drive the conversation in ways that it hasnt been driven before. He can be that “new voice” to make people answer questions they’ve never been asked before. I may in the end not vote for him but I will support him now so he can get his voice heard.

One of the things I have encountered when talking about these ideas with people is they say “Oh thats Keynesian”. Usually my response is that they misunderstand Keynesian and MMT. I say that Keynes ideas were in a gold standard regime where govt “borrowing”was the only way to spend, today borrowing isnt necessary and in fact may be counterproductive. Issuing govt debt to spend is not necessary anymore. The other thing I say is that Keynes talked about savings coming out of income, income coming out of spending and spending coming from investment, therefore investment leads to savings and NOT the other way around. Is there anything I should add to my points?

Happy New Year

The right article at the right time.

Thanks, Bill.

Dear Bill.

You said:

“The radical groups will never make progress in any widespread way until they can attack the neo-liberals on their own turf – the economics debate”.

You are joking ?

Thanks, Bill, for confirming my re-emerging, and increasingly radical inner-self.

I hope it is properly aimed.

Dear Joebhed

The motivation has to come from within. Just think that as you get older the days are getting shorter and there is a lot to be done. Nothing of consequence will happen if you adopt a conservative position, which by definition, just locks in what you see before you now.

best wishes

bill