I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Its a family affair

I am going to start a public campaign to help our friends in the financial markets. I would like all caring citizens to start donating comics and other light material and send it to the business houses so that the workers can actually read something productive during there time in the offices rather than the usual stuff that circulates. Unfortunately the usual so-called analysis spreads out into the wider research world – which means I read it too. Today we consider a classic case of manipulation to make a case. A denial of the empirical reality, a spurious claim to an historical relationship, and an assertion of an authority – the “bond markets” – that ultimately doesn’t exist. Classic propaganda but some lessons to learn as well.

I am having a musical week, so today’s title credit comes from Its a family affair played by that magic band Sly and the Family Stone:

It’s a family affair

It’s a family affair

It’s a family affair

It’s a family affairOne child grows up to be

Somebody that just loves to learn

And another child grows up to be

Somebody you’d just love to burn

…

Yes, I want to burn some of them!

Anyway, the comic appeal was prompted by something I read yesterday from Societe General Cross Asset Research. The paper entitled Popular Delusions: A global fiasco is brewing in Japan and was written by one Dylan Grice who works at SG. SG by the way are among the most rabid of them all – even the market players call them “a bearish lot”.

The Report received instant attention in the financial press soon after it was released. The right-wing UK Telegraph journalist Ambrose Evans-Pritchard extollede its virtues in his January 12, 2009 – A global fiasco is brewing in Japan – yes, he even stole the title.

Not much else about the Evans-Pritchard story is original. He just chooses to be the mouthpiece to perpetuate the myths that the financial markets analysts

The Australian press picked up on it. The Business Spectator journalist Karen Maley at least changed the title in her Bond tremors from Japan article.

She described Grice’s report as an “interesting paper that ran through the grave risks to global capital markets posed by the rapid ageing of the Japanese population”.

Grice begins with this gambit:

Japan’s government borrows from Japanese households and has done for decades. But Japanese households are retiring, and traditionally retirees run down their savings. So who will fund Japan’s future deficits, which are already within the range identified by inflation historian Peter Bernholz as hyperinflation ‘red flags’? Twenty years ago, who could predict long-term JGB yields below 1%? Who sees uncontrolled inflation as the primary risk facing Japan today?

Note we are back to Bernholz again who I discussed in yesterday’s blog – Its a hard road.

His thesis is that even though Japan has been plagued by deflation for years there is still catastrophic risk and the “Japanese are simply unable to perceive the risk of inflation because they cannot imagine it”. After all, he also wants to convince us he is literate and starts that section of the report with the very esoteric statement: “Reality doesn?t exist, only perception”. I long to be that intellectual.

So there is a huge risk but the Japanese just cannot imagine it so they are doing nothing to stop the risk. That is the reasoning.

Then we get into family mode, with Grice saying:

Of course, the cousin of inflation is sovereign default. The fiscal pressure forcing default creates pressure to print money … The insolvency of developed economy governments when account is taken of their unfunded social promises is something Albert and I have noted for some time … But as the Detroit car companies demonstrated, insolvent organizations can stay alive for as long as they can remain liquid – but illiquidity will inevitably force insolvency into the open. And there haven’t been any developed market government funding crises since the days of Bretton Woods, even though we came close following the collapse of Lehmans in 2008. So such risk is not taken particularly seriously. But a fiasco is surely brewing.

It’s a family affair

It’s a family affair

..

Cousins this time. I am wondering how the family structure was decided. Who is the father and mother of inflation? Who gave birth to sovereign default? Are the parents brothers and sisters? All important questions if we are to get to the bottom of this analysis.

And … I guess Albert needs some comics too – he is seemingly an off-sider another “strategist” as they call themselves.

But this is another one of those stories where the data doesn’t stack up, the historical experience does help but the sky is going to fall in anyway. Never let the facts get in the road of your theory, that is the lesson.

Default is about insolvency. A fiat currency issuing government (such as Australia, Japan, and the United States) never faces insolvency risk. It is impossible for them to be insolvent in their own currency.

The collapse of Bretton Woods freed governments of the binds of currency convertibility and reduced the probability of sovereign default on financial grounds to zero. The only reason a government might default now is if they saw political reasons to do so or they had borrowed too much in foreign currencies and their trade sectors weren’t delivering enough of that currency.

There were also very few defaults under the Gold Standard even though it was more likely then.

So the claim that the Lehmans collapse pushed the US Government to the brink of solvency is just plain beat-up! Just a disgrace that he would think it reasonable to print that lie.

Grice continues:

Although it is difficult to predict exactly how much debt is too much, it is clear that governments are near the mark. On the left of the following frame is a chart taken from Peter Bernholz’s classic study of inflationary episodes over the centuries showing budget deficits (as a % of government expenditures) prior to five hyperinflations. The range in the run-up to such episodes is 33% to 91%. The right chart shows the current ratios for Japan and the US

to be well within that range.

It is “clear”. To whom? Not to anyone I know who knows how the system operates. Not to anyone I know who works in central banking and/or Treasuries.

Anyway, Grice is relying on the analysis in Bernholz (you can search for it if you like – I wouldn’t bother). In his book – which will before long be remaindered then offered as land-fill – Bernholz claims that “hyperinflations resulted whenever 40 percent or more of government expenditures were financed by money creation”.

While I think Bernholz’s analysis is faulty (as per yesterday’s blog), I wonder if Grice has actually read the book. Bernholz is careful to point out that while the 40 per cent threshold is important (in his view) (page 70) that

It will be demonstrated by looking at 12 hyperinflations that they have all been caused by the financing of huge budget deficits through money creation …

So, even in this analysis “This is not true for borrowings taken up in the capital markets” because they drain the monetary base. Even Bernholz said that “13 percent of U.S. expenditures” at present are funded via central bank credits. My own calculations don’t come up with a figure like that but that is another story altogether anyway.

The point is that Grice doesn’t mention this qualification at all. He uses Bernholz for authority but doesn’t stick to latter’s story even. Instead Grice just presents the following graph (this is his “right chart”, I won’t bother putting the Bernholz chart up) and concludes that “Japan and US are well within” the hyperinflation range. The bars show the nominal budget deficits as a percentage of total government spending.

Why this matters is another story but Grice doesn’t attempt to split this percentage up into that which is backed by debt-issuance to the private sector and that which is backed by debt-issuance to the central bank (which is minscule).

But what I found dishonest was the focus on a few years without reference to history. I have looked into this issue before when I read Bernholz’s book and so you might be interested in some of the data as well.

You can get long time-series for the CPI data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and the public finance data from US Office of Management and Budget. I was able to create an monthly and annual series for inflation (annual percentage change in the CPI) from 1919 to 2009 and the government deficit as a percentage of total government expenditure from 1900 to 2009.

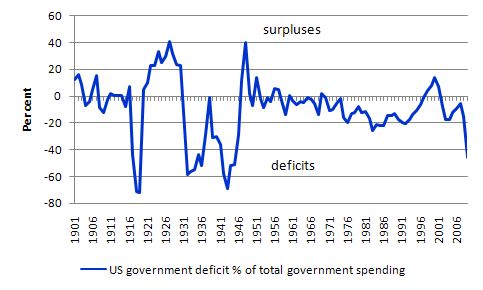

The following graph shows government spending as percentage of total government expenditure since 1901.

The points to note are that the current ratio (and not buying how much of the deficit is matched by debt issuance) is not historically large when you compare it to some of the other years, particularly during the Great Depression.

Second, whenever the US government has gone into surplus, a recession follows soon afterwards.

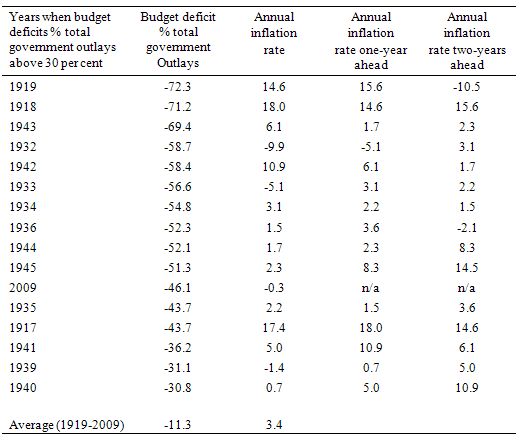

The following table shows all years when the government deficit as a percentage of total government expenditure between 1919 and 1930 was above 30 per cent along with the corresponding inflation rates in the same year, one year ahead and two years ahead. The average ratio for the entire period was 11.3 per cent and the average inflation rate was 3.4 per cent.

The table suggests no relationship between deficits as a percentage of total government spending and inflation (even out two years).

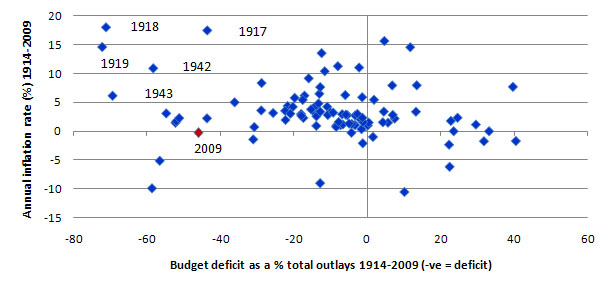

This is also confirmed visually. For example, the following chart shows the contemporaneous relationship between the two variables. Cross plots using the one-period and two-period ahead values of inflation provide even less of a pattern.

Grice says that:

Japan has run deficits for years and has seen its debt burden explode, yet it has also seen its long-term borrowing costs collapse. Indeed, if you study the Bernholz deficit chart above, it is obvious that Japan has been running “hyperinflationary deficits” for several years, yet it remains mired in deflation. Maybe this time it will be different, but I don’t think so. On a point of logic, Japan’s ability to avoid a funding crunch to date despite its rising indebtedness does not prove that it will not at some point see a funding crunch. It does prove that this can be delayed. How has Japan been able to achieve this delay? Primarily because it has enjoyed a captive market – not only were domestic savings abundant, but risk-averse Japanese investors were happy to purchase “risk free” government bonds.

But he claims that with an ageing population the captive market will decline. This Ministry of Finance paper gives an interesting account of the declining Japanese saving rate.

First, as the Japanese domestic sector reduces its saving ratio (it is now around levels that are common elsewhere after having been very high for years) it will spend more and the need for significant budget support for the economy will decline.

Second, if it was the case that the capital markets stopped buying Japanese government debt then would that stop them spending? Clearly not – they are a sovereign nation.

But Grice has another suggestion: remove the stimulus and accept the pain – “lower growth, higher unemployment and political unpopularity.” Given he doesn’t think the Japanese government would take that path he claims it:

will be imposed on … by a suddenly less generous bond market via a government funding crisis.

The financial markets ultimately cannot impose this on the Japanese government unless the latter subjects itself to the false authority of the former. As noted above, the Japanese government will always be able to spend in its own currency as long as there are real goods and services available for sale in that currency independent of what the “bond markets” say.

Ultimately, the Japanese government may wisen up and realise they don’t have to “fund” anything.

Which leads me to another story I read today in the Business Spectator by Stephen Kirchner who works at the ultra manic right-wing libertarian group the Centre of Independent Studies (which is funded by “private sector donations – from individuals, companies and charitable trusts” all who want liberty restored, by which they mean freedom from government so that business can be let loose to take what they can get and leave the pickings for the rest of us).

Why the “right-wing libertarian” tag? Aren’t all libertarians right-wingers? Definitely not! I am a libertarian and if you consult my About page you will see why.

I always bristle when characters from the CIS claim the represent the libertarian voice. The Political Compass (which is a favourite of mine) distinguishes between the right-wing and left-wing libertarians. They say:

The usual understanding of anarchism as a left wing ideology does not take into account the neo-liberal “anarchism” championed by the likes of Ayn Rand, Milton Friedman and America’s Libertarian Party, which couples social Darwinian right-wing economics with liberal positions on most social issues. Often their libertarian impulses stop short of opposition to strong law and order positions, and are more economic in substance (ie no taxes) so they are not as extremely libertarian as they are extremely right wing. On the other hand, the classical libertarian collectivism of anarcho-syndicalism (libertarian socialism) belongs in the bottom left hand corner.

The classical libertarian collectivism of anarcho-syndicalism – that’s me! Of-course, MMT applies to both camps it is just that few people realise that. It also applies to the authoritarian left and right. And few of them realise it too.

Anyway, the Kirchner article Economic policy must re-earn our respect, is another inflation beat-up story.

It says that because “financial market pundits” cannot decide whether we are lurching into high inflation or deflation indicates that “both monetary and fiscal credibility have been damaged by the policy responses to the global financial crisis”.

That is what he said! He used to work for a credit rating agency so I guess he considers that only those who work in financial markets have any insight.

The hypothesis is that the independence of central banks (so-called “increased credibility”) that was developed during the neo-liberal hey-day in the 1990s, where these unelected boffins who claimed to know how the monetary system worked used unemployment as a policy tool to reduce inflation.

The empirical evidence from the research is clear: countries which adopted formal inflation targetting (and all the flim-flam that went with – independence etc) fared no better than countries which did not buy in to the hoopla.

Further, the admissions from Greenspan and subsequent revelations about how he conducted business plus the meltdowns in the UK, Iceland, and elsewhere indicate that the central bankers once let off the leash were ill-equipped to advance the interests of the broader public.

Anyway, Kirchner longs for the days when national governments were back in surplus. I feel for these guys – I really do. They must be devastated that governments are finally showing economic leadership again and running deficits.

He says that while the central bank reactions to the current crisis “was the appropriate response” (Ok! I disagree but), it has “inevitably raised questions about the timeliness of any future normalisation of policy”. So he is one of those – wouldn’t dare claim that the crisis didn’t need government attention but now demands a contraction.

But he thinks the US Federal Reserve is now “compromising its independence and commitment to price stability” because it is “accommodating fiscal stimulus” and not pushing up interest rates.

So does he want the two arms of macroeconomic policy to be working against each other as is now happening to our loss in Australia?

No, he wants both arms to contract. He claims:

These concerns over the direction of monetary policy are perhaps less significant than the concerns in relation to fiscal policy. Governments around the world have implemented unprecedented discretionary fiscal stimulus packages, compounding the cyclical deterioration in their budget positions due to reduced economic growth.

These stimulus packages are of doubtful effectiveness in supporting demand in the short-run, not least because they undermine the credibility of fiscal policy in the long-run.

A discretionary fiscal stimulus package is equivalent to a future tax increase in the absence of a credible plan to reduce future government spending. Yet no one would consider the announcement of a future tax increase as stimulatory for current economic activity.

So there should have been no discretionary fiscal additions to the outcomes that the automatic stabilisers delivered. Exactly where would have the descent ended without the stimulus? The evidence in Australia is that the fiscal stimulus added percentage points to economic growth over the last 3 quarters and without it we would have be have endured negative GDP growth throughout 2009. I cover the latest evidence of this in this blog – Lesson for today: the public sector saved us

A paper released by the Australian Treasury in December said:

Chart 10 shows Treasury’s estimates – of the effect of the discretionary fiscal stimulus packages on quarterly GDP growth. These estimates suggest that discretionary fiscal action provided substantial support to domestic economic growth in each quarter over the year to the September quarter 2009 – with its maximal effect in the June quarter – but that it will subtract from economic growth from the beginning of 2010.

The estimates imply that, absent the discretionary fiscal packages, real GDP would have contracted not only in the December quarter 2008 (which it did), but also in the March and June quarters of 2009, and therefore that the economy would have contracted significantly over the year to June 2009, rather than expanding by an estimated 0.6 per cent.

This conclusion applies throughout the advanced world.

But the classic was that a “discretionary fiscal stimulus package is equivalent to a future tax increase”. Equivalence is a mathematical state. There is nothing credible in this claim. Even during the gold standard days it was untrue.

Taxes go up and down over time depending on fashion (that is, ideology) and the genuine need (and political decision) to give the private sector more or less purchasing power. To think that over some finite period (which is the implication) that taxes have to rise to cover the deficits is historically without foundation and has no basis in credible economic theory.

The claim comes from the simplistic mainstream macroeconomic textbooks where to fit the story (usually with a graphic) on one page so they limit the payback period to a few only. Accordingly, they cut taxes in period 1 and “fund” it with debt-issuance. In each subsequent period, bonds are issued to cover the interest payment on the existing debt and plus the deficit each year as a result of the tax cut.

So the debt piles up (and they usually distort the scales to make it look bad) and so after three periods, the taxes have to be raised by more than the initial cut to pay back the debt accumulation. They then conclude growth is impaired because the taxes promote disincentives to produce and so on.

The analysis always leaves the students with the view that this all has to happen in a finite (narrow) time frame – so tax rises are coming soon – and that the overall impacts are disastrous.

Those students that are clever enough to undertake history at the same time soon learn that these economic models are nonsensical and just blatant propaganda.

Kirchner is just a propaganda machine like most mainstream economics commentators in this regard.

Taxes may go up but not because the government needs to “finance” its net spending. Further, the idea that a balanced budget is normal and a deficit is an aberration is about as stupid (and ill-informed) as saying it is normal for the private sector not to ever save on average and that current account positions should always be balanced.

Further if you want to admit that historically current account deficits are the norm (which they are for Australia and most countries) then to claim that a balanced budget (or even a surplus) is desirable means you must also be arguing that is normal (and desirable) that the domestic private sector (as a whole) is on average dis-saving and increasingly building up debt.

If you understand the national accounting relations that link the macro sectors together you will also understand that that outcome is inevitable should the government eliminate deficits when there are external deficits.

Conservatives don’t argue that the domestic private sector (as a whole) should on average be dis-saving and increasingly building up debte but that just means they fundamentally misunderstand the macroeconomic aggregates because every time they call for budget surpluses (when there are external deficits) that is exactly what they are arguing for.

Now the link between Kirchner’s article and Grice is that Kirchner also claims the so-called ageing society will generate fiscal blowouts. Please read my blog – The myths of the ageing society debate to see why the ageing society debate is another one of those beat ups designed to stop governments from using deficits.

Conclusion

Go and dig up those old comics and get them in the post. They guys need something better to do.

I wonder what the likes of Grice, Evans-Pritchard and Maley will write once my elaborate comic donation plan takes hold. I guess we will start to read about how “Phantom beats off evil neo-liberal pirates” or “Donald and Minnie go shopping with their Job Guarantee pay check”. It will be a welcome relief.

That is enough for today!

“The classical libertarian collectivism of anarcho-syndicalism – that’s me!”

Are you an anarchist ??? 🙂

Dear Bill,

Very interesting how Bernholz claims that “hyperinflations resulted whenever 40 percent or more of government expenditures were financed by money creation”.

He should have said 42 and cited The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy as a reference to back up his claims.

My opinion is that in absolute terms 100% of government spending is financed by money creation. How else is it even possible when they are the monoplist suppliers ?

Cheers

“Further, the admissions from Greenspan and subsequent revelations about how he conducted business plus the meltdowns in the UK, Iceland, and elsewhere indicate that the central bankers once let off the leash were ill-equipped to advance the interests of the broader public.”

IMO, the fed and central bankers are ONLY interested in advancing the interests of the spoiled and the rich, including themselves.

Here is how I think it is best to look at the situation.

(S-I) of the rich = (G-T) of the gov’t minus (S-I) of the lower and middle class

That should be savings of the rich equals dissaving of the gov’t (which the rich want to be gov’t debt) minus savings of the lower and middle class (plus their dissaving).

What the rich are trying to do is “steal” the real earnings growth and retirement of the lower and middle class from productivity growth and give it to themselves thru debt enslaving the lower and middle class using price inflation targeting as an excuse.

«IMO, the fed and central bankers are ONLY interested in advancing the interests of the spoiled and the rich, including themselves.»

As they see it, and it is a view shared by many (perhaps most in the USA) voters, they are defending the productive heroes of wealth creation from the ravenously greedy exploitation of the parasites in the bottomost 80-90% of the population who produce and create nothing.

That is they are advancing social justice and defending the right of workers to the fruits of their productivity and creativity. As Senator Gramm stated, the CEO of Verizon was the most exploited worker in the USA, because he was paid severance worth only a few dozen million dollars instead of the billions he had earned thanks to his superior productivity and creativity.

As one of them put it, it is “God’s work”. 🙂

«in absolute terms 100% of government spending is financed by money creation»

That is a ridiculous reduction to absurdity. “financed by” and “expressed in” are very different concept; “financed” implies *net* money creation.

The big problem of reasoning above, both the loathsome neoliberals and Billy is the dreaded “other things being equal” implicit assumption.

I have no difficulty believing that if you take a healthy economy and suddendly, other things being equal, the state expands its purchases of goods and services with net credit, it will generate a colossal rise in the level if prices of something — this indeed has happened between 1995 and 2005 in most “anglo” countries, leading to enormous (and politically motivated) asset price bubbles.

«Further, the idea that a balanced budget is normal and a deficit is an aberration is about as stupid (and ill-informed) as saying it is normal for the private sector not to ever save on average and that current account positions should always be balanced.»

Only in ex-post national accounting terms, in which “private sector” and “savings” are defined in very peculiar “terms of art” ways.

What matters in the end is the level of “physical” provision of goods and services, the balance of payments, and the income distribution resulting, not ex-post accounting categories. If the latter are misbelieved as mattering, there is another “other things being equal”.