Here is Episode 4 in our weekly MMTed Q&A series. There will also be some music for those who like to find some different music. This week we experimented with a different format and further reduced the length.

Questions and answers 1

I get a lot of E-mails (and contact form enquiries) from readers who want to know more or challenge a view but who don’t wish to become commentators. I encourage the latter because it diversifies our “community” and allows other people to help out. The problem I usually have is that I run out of time to reply to all these E-mails. I apologise for that. I don’t consider the enquiries to be stupid or not deserving of a reply. It is just a time issue. When I recommitted to maintaining this blog after a lull (for software development) I added a major time impost to an already full workload. Anyway, today’s blog is a new idea (sort of like dah! why didn’t I think of it earlier) – I am using the blog to answer a host of questions I have received and share the answers with everyone. The big news out today is Australia’s inflation data – but I can talk about that tomorrow. So while I travel to Sydney and back by train today, here are some questions and answers. I think I will make this a regular exercise so as not to leave the many interesting E-mails in abeyance.

Question 1:

If money is a government monopoly, and if it is “money” that facilitates all economic operations, it would seem to follow that government would issue money in accordance with the level of productivity, so as not inflate the value of its currency, and effectively rob people of the value they create. Is this right?

First, the national government (the consolidated central bank and treasury) does not control the money supply in a modern monetary economy with a flexible exchange rate such as in Australia or the US. Government transactions with the non-government sector add to bank reserves and currency notes and coins (thadt is, add to the monetary base) but credit creating activities of the commercial banks – loans creating deposits – add to what we call the broader money supply.

Second, the current stock of “money” nor the growth in the monetary base tells you much about the inflation risk an economy is facing. As we have seen in the current crisis, bank reserves have skyrocketed as central banks have expanded their balance sheets via quantitative easing and other operations yet most economies are battling with deflation rather than inflation. To understand what is going on you might like to read these blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and its partner Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

The important point is that those who want to draw a connection between the money supply (or its rate of growth) and inflation always invoke (whether they know it or not) the Classical Quantity Theory of Money which was discredited in the 1930s (in part, by Keynes’ General Theory – 1936).

An increase in high powered money (via say net public spending) does not directly impact on prices. The Quantity Theory of Money begins with an accounting identity MV = PY, where M is the stock of money, V is the velocity or the times the stock turns over per measurement period, P is the price level and Y is the real output level.

Clearly from a transactional viewpoint this has to hold. All the transactions (left-hand side) have to equal the value of production (right-hand side). That doesn’t get us very far.

So Classical theorists (and monetarists and more modern variants) had to make some assumptions or assertions about the behavioural nature of the variables underlying the accounting identity. What they did was assume that V is constant and ground in the habits of commerce – despite the empirical evidence which shows it is highly variable if not erratic. They also assume that Y will always be at full employment because they invoke flexible price models and assume market clearing – so they take Y to be fixed. This is a case of blind devotion to theory stopping the economist looking out the window and seeing regular periods when productive resources are anything but fully employment.

But with these assumptions – any child could then conclude that changes in M => directly lead to changes in P because with V assumed fixed the left-hand side is driven by M and if Y is assumed to always be at full employment then the only thing that can give on the right-hand side of the accounting identity is P.

While first-year students struggle to learn this theory and think it is high science – it is almost mindless when you think about it. Look for it prominently displayed in Mankiw.

You should easily be able to see the flaws. The assertion that the real side of the economy (output and employment) are completely separable from the nominal (money) side and that prices are driven by monetary growth and growth and employment is driven wholly by the supply side (technology and population growth), rests on the assertion that the economy is always at full employment (quite apart from the nonsensical assumption that V is fixed)..

Anyone with a brain could tell you that if business firms can respond to higher nominal spending (that is, higher $ demand) – either by increasing production or increasing prices or increasing both – and they cannot increase production any more (because the economy is at full employment) then they must increase prices to ration the demand.

That is a basic presumption of modern monetary theory (MMT). But typically, firms prefer to respond to demand growth in real terms to maintain their market share and thus invest in new capacity if they think spending will grow in the future and vice versa.

The overwhelming evidence is that the macroeconomy quantity adjusts rather than price adjusts to nominal aggregate demand fluctuations when there is excess capacity. Otherwise firms risk losing market share.

So, when the economy is in a state of low capacity utilisation with significant stocks of idle productive resources (of all types) then it is highly unlikely that the firm will respond to a positive demand impulse by putting up prices (above the level that they were before the downturn began). They might stop offering fire sale prices but that is not what we are talking about here.

This should discourage you from automatically linking growth in the monetary base and inflation. There is no link.

Inflation is driven by nominal aggregate demand growth that exceeds the capacity of the economy to respond in real terms – that is, to increase output. There are a myriad of reasons why this situation could emerge and some of these reasons implicate poor government policy decisions.

Question 2:

And if the legality of this money stems from the fact that it alone is accepted in payment of taxes, but at the same time it is a government monopoly freely creatable, then why pay taxes? Why can’t the government simply create money to be balanced by a corresponding creation of productive assets in the private sector for goverition nment use, as in military protection, or to be used in generating public sector employment?

I don’t understand the need for taxes in this scheme–assuming I’ve understood it to this extent.

There are two separate strands of discussion in MMT that are relevant here.

First, going back to first principles you have to ask how a government establishes a demand for its fiat currency, that is, a unit of currency which is not based on any valuable commodity and is otherwise worthless. So imagine there is a local economy already in place and a colonial authority comes along and takes the place over. It wants to move resources from the private sector to the public sector to build infrastructure and whatever. In the absence of slavery how will it encourage the local inhabitants to offer their labour power and other resources in return for payment of the government’s otherwise valueless fiat currency (bits of paper)?

The answer is that it tells the local population that it must pay a weekly tax in the unit of currency issued by the government. The local population then realise that to pay the tax (which is enforceable by the authority of the government – ultimately its prison system backed by its police and military) it has to get hold of units of currency issued by the government. Immediately, there is a demand for that currency and people are willing to sells goods and services including labour power to the government in return for payment in the government’s currency.

Later as the currency becomes widely accepted, people have other reasons for demanding it – its becomes a readily acceptable means of exchange (and all the other reasons you will see in macroeconomics textbooks). But at the abstract level of first principles, fiat currencies are tax-driven in the sense I have explained.

This is very important in some developing countries that use dual currencies (such as the local currency and the US dollar). While people use the US dollar for many transactions, as long as the national government can enforce its tax laws, there will always be a demand for its currency and this allows the national government to advance public purpose via its own net spending.

You won’t see anything about this in mainstream macroeconomic textbooks or orthodox books on development economics. They are blind to the realities of the monetary system. Please re-read my blog on the Business Card Economy to see how localised a modern monetary system could operate.

Second, in the blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – I discuss how taxes are an important tool the government can manipulate to regulate aggregate demand and maintain its desired balance between public and private sector activity. Increasing or decreasing taxes are a way the government can reduce or increase the purchasing power held by the non-government sector (primarily the private domestic sector).

Regulating demand growth is important in terms of maintaining price stability. So if there is excess capacity and the government desires more private activity (that is, it wants private demand to take up the slack) then it might reduce taxes. Otherwise it can simply increase its own net spending and take up the slack that way. The opposite is the case when the economy is approaching full capacity. Then the government may increase taxes to stifle demand and keep a lid on price inflation.

In all cases, the tax decisions have nothing to do with “financing” public spending. The government in a fiat currency system is not revenue-constrained as is noted in the question.

Finally, taxes are also a way that the government can alter the relative price of different goods and services and discourage or encourage production and consumption of the same. In this sense, taxes function to direct usage into goods considered beneficial and away from goods that are considered damaging. The classic example is taxes on tobacco. But carbon taxes fit into this category as well.

I then receive E-mails such as this one – which I have edited (all my edits are in square brackets) to preserve anonymity given the likelihood that the instructor would become vindictive.

Question 3:

I would appreciate some advice on the following:

Just briefly, I am in my first year of economics but I have found myself somewhat dissatisfied with what is being taught. I’ve been reading around about the various economic schools and have found myself in agreement with the Post Keynesian School and … [my reading] … has recently … drawn me to Modern Monetary theory (MMT).

I had a macro debate [at university recently where I argued the case for fiscal policy] … Naturally I felt that it would be a perfect opportunity to get a better understanding of MMT and I thought I would argue from that perspective; I somewhat regret this decision in retrospect. I read through a lot of your blog posts and other related material.

[At the debate the lecturer turned on me accusing me of being dogmatic and claimed that the expansion of fiscal policy to reduce unemployment etc would upset financial markets and have] …. crowding out effect, higher taxes, inflation and higher interest rates … I had addressed each of these points … [in my presentation] …

My reason for writing is I would appreciate it if you could point me in the direction of the literature so that I may formulate a rebuttal to …. [the lecturer’s claim] … Thank you for the taking the time to read this email, I’m sorry about the length. I would have posted this on your blog but I didn’t want to cause any issues particularly if my lecturer stumbles across the page.

So the dirty thought-police are intimidating the free thinking of students. This is a typical story about the way undergraduate and post-graduate economics programs are taught. Ridicule is one of their most advanced art forms for exerting discipline in the courses they teach followed by using their marking pen at final examinations to ensure bad ideas do not get out there.

I can tell you many stories about this sort of behaviour from personal experience and the experience of 30 years in the profession (as a student then academic progressing to the top of the hierarchy). The mainstream cannot take criticism. Essentially any liberal-minded student soon sees through the cant in mainstream macroeconomics – they soon realise that it doesn’t bear very much correspondence with the empirical reality. But like all paradigms, and economics isn’t alone here, social controls are used to reduce the likelihood of errant thought.

Further, the profession tightly controls the academic journals (who publishes what); grant funding bodies (who gets what for what); and the appointments processes (who gets jobs and is able to teach). While some non-mainstream economists get through (for example, yours truly) for various reasons the vast majority do not. You will find a a host of “progressive” would-be academics working outside of the university system. Not all of these would have made it anyway but more than actually get through the paradigmic defence mechanism would have made it.

But the other point is that this lecturer’s behaviour only tells me that he/she is not qualified to teach students macroeconomics as it applies to modern monetary systems – which means just about everywhere. He/she doesn’t understand even the most basic operational principles government the monetary system we live in. He/she probably learned economics from Mankiw or similar and is too dim-witted (and lazy) to expand any further than that.

It is clear that expansionary fiscal policy puts downward pressure on interest rates because it creates excess reserves in the banking system.

It is clear that the central bank sets interest rates.

It is clear that taxes do not fund government spending and do not necessarily rise or fall when government spending is increased or decreased.

It is clear there is no necessary correspondence between fiscal policy variations and inflation except that if net government spending drives nominal aggregate demand above the capacity of the real economy to absorb it then you get a problem and if governments use fiscal drag (running budget surpluses) to open a spending gap, eventually deflation results. These are extreme government behaviours and not at all consistent with prudent and responsible fiscal policy management.

The problem is that the deficit terrorists such as this lecturer always invoke the outlier behaviour – although there is limited historical evidence of it. He/she should resign immediately.

But we could extend the lecturer some grace if he/she wanted to expand their mind. I would recommend familiarity with the essential principles of modern monetary theory (MMT) which are developed in Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | and Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – plus other blogs. Go to Debriefing 101 for a collection of blogs covering the first-principles of MMT.

Question 4:

I am having a difficult time understanding how the rise in commodity prices does not signal future inflation. The Goldman Sachs Commodity Index is up 46% this year. Yes, I did see that is quite a bit lower from the 2008 highs, but still, it’s building steam towards that range gain and I don’t understand how we keep from having inflation, especially given the Fed’s inability to properly use the Taylor Rule – i.e. I’m sure they will not tighten policy quickly enough.

As mentioned, I am very new to your blog, but do enjoy it on a very regular basis; however, I’m stuck on a problem of how to rectify current policy, modern economic theory, and how we not blow ourselves up with inflation over in the near term.

It is a common misperception that a relative price change is equal to inflation. Inflation is the continuous rise in the general price level (that is, all prices). So a rise in a particular asset class does not amount to inflation although it does alter relative prices (the prices relativities between individual goods and service). Relative price changes can be very disruptive if they also cause terms of trade changes and sectoral imbalances.

So the concept of the Dutch Disease is an example of this. In Australia at present, the mining sector is strong because world demand is high for base metal commodities and this has had the effect of pushing the $A upwards. However, other exporting industries (for example, manufacturing and agriculture) are not enjoying the same bouyancy in demand for their output but have to face the terms of trade impacts on their margins of the exchange rate appreciation.

Getting back to the point what happens in one sector of the economy may or may not have implications for movements in the general price level. This can occur in one of two ways. First, as above, if aggregate demand becomes so strong because say net exports are very strong then you could get inflationary pressures. Second, if a strong industry bids up domestic resource prices which then spread out to other industries who are not enjoying the increased capacity to pay. A wage-price spiral can emerge in this case under a “battle of the margins” scenario.

Ultimately, fiscal policy has the capacity to deal with both situations to prevent a major inflation emerging. We cover these options in our recent book – Full Employment abandoned.

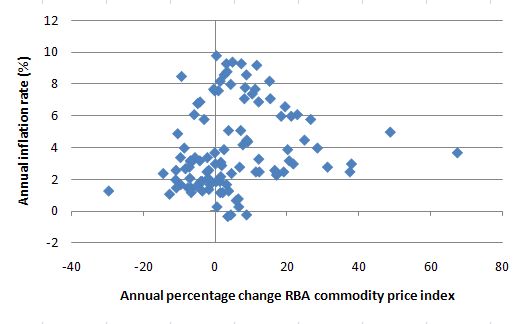

The empirical reality would suggest that these conceptual linkages are not strong however. The following graph charts the annual growth in (quarterly) commodity prices (the RBA Commodity Price Index) on the horizontal axis and the annual inflation rate on the vertical axis from September 1983 to September 2009. You can get the data from the Reserve Bank of Australia – go to statistics.

The graph suggests that there is no obvious relationship between the strength of the commodity price growth and the inflation rate. It is consistent with recent history where commodity prices have been at record levels yet inflation has been easily contained.

I often get questions such as the following.

Question 5:

I understand the paradigm what you and others (Warren Mosler) are explaining.

My question is how do I use this knowledge for my personal investments? How have you used it? What is the link between this knowledge and its actual practical use?

The simple answer is that billy blog is not a financial advice service. I think of it as an outreach of my academic work – which means it is primarily intended as an educational resource. I also consider it to be a source of advocacy whereby I can say what I like – which means it is a political vehicle. While it is clear to me where the education stops and the ideology begins I think that sometimes readers are less clear and conclude that MMT is a 2010 version of the Communist Manifesto.

There is nothing ideological about MMT. But many things I say about what should be done after drawing on my understanding of MMT are ideological. For example, the whole concept of “public purpose” is ideological. But once defined to reflect my (our) values – say, as a job for all, then MMT tells you very clearly the policy framework that will and will not achieve that aim.

Anyway, how you use the principles of MMT in your personal life is your own concern and I am certainly never holding out any financial advice about personal investments etc. But having said that I do think the theoretical structure that we have built up on the back of earlier writers in related areas (Marx, Kalecki, Keynes, Lerner, Minsky, and many others) serves as a powerful tool to combat the myths perpetuated daily by the mainstream of my profession.

I think MMT should empower progressive groups who are continually being hoodwinked by the mainstream machine. My experience is that the mainstream cannot deal with a well-argued MMT explanation of the way the system works and specific historical episodes. Ask them how to explain Japan and they fail badly. Ask them how to explain the current crisis and you will find nothing at all in the mainstream curricula which would help you understand what has been happening. Which is why it happened in the first place?

Progressive groups can use MMT to mount a fight-back to reclaim policy space and make fundamental changes to the way the economy operates and interacts with the broader society. So practically I would see my work (and that of my close colleagues around the world) as providing the basis for political mobilisation. That is why I attacked the Greens last year. They are sound on environmental grounds (and largely social grounds) but thoroughly neo-liberal in terms of their macroeconomic economic policies. The latter makes it virtually impossible to achieve the former. Please read my blog – Neo-liberals invade The Greens! – for more discussion on this point.

Question 6:

I am a lawyer but have maintained my university interest in economic studies. I enjoyed your paper A modern monetary perspective on the crisis and a reform agenda … [note: the link takes you to the working paper version of this paper which you can get for free … the published version is protected by the publishing company] …

I was wondering if anyone has done calculations on how much GDP and the tax base would increase if we had full employment (at say 1973-4 levels around 1%). I know it would be heavily premised on money wage levels but assume an

initial calculation could be done on minimum wages. It does however seem to me that such a calculation could be done without intruding too much on other linkages such as currency and exchange rates.Bill Hayden used to ask Treasury questions in the late 1970s about the full employment deficit, how much additional expenditure would be required to ensure full time employment for all who want it, and over the budget cycle of around three to five years it was as I recall fairly neutral but this I assume is now out of fashion.

I have covered this issue in several blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job!. and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers and The daily losses from unemployment.

The fact is that the GDP losses from having persistently high unemployment are the largest economic loss of all the inefficiencies. So while the neo-liberals were obsessed with so-called “structural inefficiencies” or “microeconomic inefficiencies” by which they usually mean government regulation on a business free-for-all or minimum wage laws to stop the low-skill workers being coerced through starvation into working for Dickensian wages all the empirical work done on this topic, including my own over many years shows that the macroeconomic losses are so large that nothing comes close.

The late James Tobin coined an expression – “how many Harberger triangles can you fit into one Okun Gap?” Answer: more than you can count. The triangles are those hatched areas in microeconomic textbooks that are meant to show deadweight losses arising from prices or wages being out of kilter with the so-called perfectly competitive ideal – so they are the so-called microeconomic inefficiencies. The Okun gap is the unemployment that you have to endure for each percentage point that real income is below its potential.

The concept of the full employment deficit is another one of those reasonable concepts coming out of the Keynesian era that has been perverted by neo-liberals to reduce the impact of their attacks on fiscal policy. It is now called the (now called the structural deficit. The difference in terminology is not unimportant and refers to their spurious claims that the full employment level of unemployment is now higher than it used to be because “structural factors” (for example, government regulations etc) has distorted the market optimum. If you believe any of this bunkum you will believe anything.

To see why this has distorted our judgement of the true impact of the existing policy stance, we start by observing that in an accounting sense, the federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus we conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are automatic stabilisers operating. To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget measure. This is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

Much of the debate centres on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

Things changed in the 1970s and beyond. At the time that governments abandoned their commitment to full employment (as unemployment rise), the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefining full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

NAIRU theorists then invented a number of spurious reasons (all empirically unsound) to justify steadily ratcheting the estimate of this (unobservable) inflation-stable unemployment rate upwards. So in the late 1980s, economists were claiming it was around 8 per cent. Now they claim it is around 5 per cent. The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate. In Australia, it still dominates the Treasury and the Reserve Bank modelling.

Further, governments became captive to the idea that if they tried to get the unemployment rate below the NAIRU using expansionary policy then they would just cause inflation. I won’t go into all the errors that occurred in this reasoning. My PhD was in part about all this and in our recent book – Full Employment abandoned – we cover this stuff in detail.

Now I mentioned the NAIRU because it has been widely used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then these clowns concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

So they changed the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance to avoid the connotations of the past that full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels. Now you will only read about structural balances.

And to make matters worse, they now estimate the structural balance by basing it on the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So the concept of a potential GDP in the mainstream macroeconomic parlance is not to be taken seriously as being the descriptive of a fully employed economy. Rather they use the devious shift in definition in mainstream economics where the the concept of full employment is not constructed as the number of jobs (and working hours) that which satisfy the preferences of the available labour force but rather in terms of the unobservable NAIRU.

Question 7:

… do you have an off-line way to read all your blogs? I run an Australian manufacture and export business, it keeps me very busy, but I do have time in aircraft from time to time that offer an ideal opportunity to catch up, if I could load it all up on my netbook …

Not specifically. Each year I plan to produce a PDF volume – billy blog 2009 – which will be the complete works without comments (the latter because I don’t own the copyright to them).

You can Subscribe to billy blog by Email via Feedburner – so you can read it on your mobile phone if you access E-mail that way. But you do not get the graphics as it is text-based only.

You can also subscribe to it via RSS via this link – which means you can download it into your computer and browse the content off-line.

Or you can adopt the environmentally unsound practice of printing it off each day which if I find out you are doing I will send the police around to stop it.

Any other suggestions out there?

Question 8:

I have been reading your blog with great interest. I did A-Level economics here in England but went no further. Over the last couple of years … I have read quite a lot about economics and it is pretty confusing because no one seems to agree on anything!

However I have found a certain logic to your posts … and I was hoping; can you recommend books/textbooks to me to read? Your thinking does seem quite ‘alternative’ but then you are a Professor of Economics at a University so I figure there must be books your students read.

There is very little information out there in book form as yet. Randy Wray and I have two books emerging (hopefully this year) – a principles textbook for university use and a book on development studies.

Randy Wray’s book Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability is very easy to read and excellent especially in the historical development of monetary systems.

Warren Mosler has written some lovely pieces which are available at home page. I recommend you read Soft Currency Economics and Full Employment AND Price Stability.

Finally, my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned provides a lengthy critique of mainstream employment and inflation theory and develops the MMT alternative in detail.

Other than we have published extensively in the academic journals and you can search for our work. Most of it it available in working paper form for free (these are versions that are prior to final journal publications). Just visit the CofFEE home page and go to working papers.

Question 9:

Why do you think the notion of deficit spending having to be financed solely by governments selling bonds continues to exist? Do the mainstream economists in Government really believe it would be inherently inflationary?

Furthermore, would the policy of Quantitative Easing not be the equivalent of this non debt-creating deficit spending? For example; the Government in Britain is in deficit around £200 billion this year and is selling bonds for this amount. The central bank has created £200 billion of new high-powered money and is primarily buying back Government Bonds with this money. So essentially the the central bank is giving the Govt £200 billion to finance the deficit spending. Am I missing something here? Why is it never described this way?

First, the deficits under a gold standard had to be financed by debt because the stock of money was limited by how much gold the nation held. Please read my blog – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail – for more discussion on this point.

The fact that we moved to non-convertible currencies after 1971 meant that the national currency-issuing government no longer faced any financial constraints. Of-course, this change in the monetary system coincided with the re-emergence of the neo-classical (then Monetarist) paradigm as the OPEC oil price hikes caused policy dislocation in the face of very severe inflation.

So it served the ideological interests of the orthodoxy to continue to perpetuate the claim that fiscal policy was financially constrained. They knew they could beat-up on the rising debt at any time (witness the present day!) and in that way they could politically limit the capacity of governments to net spend.

It is no coincidence that since that time hardly any nation has returned to full employment and persistent unemployment and now rising underemployment has defined the period.

In terms of quantitative easing please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more detailed discussion. But quantitative easing doesn’t add any new net financial assets to the non-government sector. It is in fact an asset swap – bonds (etc) held by the non-government sector are swapped for additional bank reserves.

On the other hand, fiscal policy creates (deficits) or destroys (surpluses) net financial assets in the non-government sector. QE doesn’t give the national government anything. And neither does the national government need “anything” in order to spend. Only financially constrained economic units require “something” in advance in order to execute their spending ambitions. These units exist in the non-government sector (households, firms etc) and also the government sector if they are sub-national governments (like local or state governments in a federal system). A national currency-issuing government doesn’t need to finance its spending.

Question 10:

… I believe … that MMT suggests that the govt/central bank has the ultimate ability to decide on the overall (aggregate) reserves in the economy. Thus it is their actions that have caused the current reserve explosion due largely to QE.

Here is the reason I agree but also disagree. In the first instance the action under QE provide an immediate bang to banking reserves. But why in my opinion this “thinking” ultimately fails is the longer that the monetary base is “disturbed via QE” combined with very low overall rate structure (in some sense these two items are correlated) the greater the probability/propensity – call it flow of funds – into “alternative reserves”. The net flow into these alternative reserves is what in effect “sterilizes” the monetary base after prolonged QE stimulation/disturbance.

I would then go on to suggest that previously gold was it, however in today’s financialised/packaged/customised ETF world “alternative” reserves base are springing up everywhere.

Is this effect a flow outside of your MMT model?

First, the central bank sets the price of reserves but stands ready to provide whatever volume of reserves are required to support the credit structure. This is a different statement to the opening statement being made.

Second, there is a close connection between short-term interest rates and the level of reserves and this drives central bank operations. When there are “excess” reserves – that is, levels that exceed reserve requirements (if any exist) and the minimum levels required by banks to satisfy clearing needs – then there is always downward pressure on rates unless the central bank: (a) pays a support rate on excess reserves; or (b) drains the excess through bond sales. The central bank can always induce the reserve movements they desire to maintain control of their policy rate by setting the price of reserves relative to any bond sales or purchases they deem appropriate.

Third, banks can clearly choose to invest in other assets – other than, holding excess reserves and/or government bonds. Those portfolio decisions are not costless though and the central bank has the capacity to influence the “profitability of the decisions” by pricing reserves accordingly.

But this sort of decision is what MMT refers to as horizontal leveraging and they all net out to zero. What other consequence do you anticipate these diversifications having in a macro sense? They don’t alter the capacity of the central bank to set the interest rate and the term structure and they don’t impact on the capacity of the treasury to net spend.

Question 11:

… Had I been exposed to the tenets of MMT while doing my undergraduate economics degree, I might have considered continuing in the discipline.

I enjoyed reading your recent post on the Great Depression and would like to encourage more on this topic as I am trying to understand better the economy-wide dynamics and real-time response by market participants that occurred as prices began to fall. I was particularly interested to hear that inflation fears were rampant then as well. On this note, the reason for my message is to ask where I might be able to find an application of MMT to the inflation of the 70’s and the ensuing response by Paul Volker (either by you or another of the followers of the MMT approach) as I have as yet been unsuccessful searching on my own. I feel that much of the inflation hysteria we are currently facing is anchored to this prior period. From what I remember, my macro class (in the mid-80’s) taught that inflation expectations (born from the oil crisis) codified in wage contracts was the primary fuel to the inflation fire that required dousing by Volker’s raising of interest rates. What say you and the other proponents of MMT?

I noticed that you are currently working on an MMT textbook. Until your book comes out, is there a currently available text that I could read?

Students are probably better advised to steer clear of studying economics given the state of the profession. It is far better to sneak up on it via liberal arts courses where you learn politics, sociology, philosophy and other useful social sciences and then take some economics and give the lecturers hell with your superior knowledge of broader social realities.

The inflation of the 1970s was not the same beast that the deficit terrorists are telling us is just around the corner now. In the mid 1970s there was a huge price rise in oil as the OPEC cartel flexed its muscles and knew that the oil-dependent economies had little choice, at least in the short-run, but to pay up. This represented a real cost shock to all the economies – that is, a new claim on real output. The reality is that some group or groups (workers, capital) had to take a real cut in living standards in the short-run to accommodate this new claim on real output.

At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants. The resulting wage-price spiral came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred. Another way of saying this is that there were too many nominal claims (specified in monetary terms) on the existing real output. This is sometimes called the “battle of the mark-ups”; the “conflict theory of inflation” or the “incompatible claims” theory of inflation. Sometimes this is referred to as “cost push” inflation because its initial source is a push upwards in costs that are then transmitted via mark-ups into price level acceleration especially if workers resist the real wage cuts that capital tries to impose on them – to force the real costs of the resource price rise onto labour.

Ultimately, the government can choose to ratify the inflation by not reducing the nominal pressure or it can break into the wage-price spiral by raising taxes and/or cutting its own spending to force a product and labour market discipline onto the “margin setters”. The weaker demand forces firms to abandon their margin push and the weakening labour markets cause workers to re-assess their real wage resistance. That is ultimately what happened in the 1970s.

However, under a Job Guarantee policy, the labour market slack required to discipline the wage-price spiral would manifest as a redistribution of workers into a fixed price employment sector (the JG) rather than under a NAIRU approach (the current approach) that forces workers into a buffer stock of unemployed. MMT tells us that the welfare losses of the latter are much large than under the former.

MMT also tells us that the national government can always afford to buy the services of any idle labour that wants to work. But the important part of the inflation control mechanism in the JG is that the government should not buy this labour at “market prices” but rather pay a living minimum wage. At any time the private sector can re-purchase the labour services by paying a wage above this.

Question 12:

From reading your blog I gather that the current problem in the US is not liquidity, as the banks have received so much bailout money and are able to borrow at 0% interest form the Federal reserve, but rather it is a lack of opportunities for investment or trust that is causing banks not to invest and thus the large amount of unemployment. From what I have read the solution to this according to MMT would be for the government to hire these idle workers by directly spending on some public project. This would create consumption which would then create investment opportunities which banks could then start lending to etc. I know that is a bit quick and dirty but do I have the basics down?

That is quick and dirty but fine by me. The banks never really had a liquidity problem – loans create deposits and in lieu of other sources (lending to each other) the banks can always then get the requisite reserves from the central bank (at a price).

There were some banks with capital issues for sure but in general the so-called “credit crunch” was largely because banks became extremely risk-averse (so they upped the requirements for credit-worthiness) and there was also a dearth of credit-worthy customers (because expectations of the future was very bleak at the height of the crisis).

A Job Guarantee, which would act as a superior automatic stabiliser, would put an effective floor into the deflationary process by stabilising aggregate demand and allowing the government additional scope to devise other fiscal interventions that it deemed appropriate given the overall state of aggregate demand.

This person then continued to ask an additional question.

Question 13:

My question is this doesn’t the US government already have a massive spending deficit caused by the Iraq and Afghanistan wars? Why has this not spurred the kind of consumption that would create investment and employment say through defense contractors, weapons manufacturing and even logistical support functions for the military such as food service and intelligence as much of this has been privatized? Additionally the need for troops is an employment opportunity though obviously not the most attractive one. Is this because the war is seen as such a bad bet? Or is the military sector of the economy just not big enough to create the necessary demand for workers? This

is hard to believe as in the US war is extremely big business..

The US government does spend an enormous amount prosecuting its war ambitions and this spending does support a large employment base. That is clear. Whether it is sensible to support employment in this way is a matter of values. But the reality is that with 10 per cent unemployment (which is really 17 per cent if you count those who have given up looking for jobs) then it is clear that the net position of the US federal government is inadequate if its aim is to support aggregate demand at levels consistent with full employment. This is also evident from the fact that capacity utilisation (that is, capital usage) is running just below 70 per cent when in usual times it would be in the high 80s.

So the answer is your answer: the military spending though huge is not sufficient to generate enough domestic demand to fully employ the workforce either directly or indirectly through the multipliers that the expenditure generates.

People have a very poor sense of proportions in this regard – about what is required. They are continually being berated by the deficit terrorists that slight changes in net public spending positions are disastrous. So they lose all sense of what scale of public intervention is required to ensure the private sector can achieve its desired saving levels and all of them can have a job.

It is one of the great and tragic ironies that the very groups that stand ready to benefit from public intervention are the same people that the ideological warriors use to undermine it.

Question 14:

I got into a bit of a blog argument on another blog (Angry Bear) related to the US Social Security Trust Fund. Someone had made the comment that more public debt needed to be issued as the boomers retired because the trust fund money “had already been spent”.

I tried to relate this to an individual buying a Treasury bond – the bond is offered because the government has authorised a debt level and the Treasury has determined that money is needed to “fund” spending. So, they offer bonds at a particular interest rate, I buy one (a small one) and put it in my drawer. I receive some interest. On maturity, I head down to my local Treasury office, present my bond and they give me currency.

Now, at that point is the bond extinguished and the government debt reduced by the amount of my redemption? I would think so – but this blog argument has my head turned around.

When I purchased the bond, I assume the government “spent” my money – my point being that when I redeemed my bond, the government did not have to “save” my money to redeem it – and they didn’t need to reissue additional debt to redeem my bond, which seems kind of silly when I think about it.

If this is the case, then what is the difference with the Social Security Trust Fund? The SSTF had excess dollars, they purchased these Special Issue Treasuries (not publicly trade-able, but redeemable on demand). The government “spent” the money, and the total US debt balance includes the Trust Fund balance.

So what happens when Social Security starts redeeming these securities? They go down to the Treasury department, present the bonds and get currency to spend for benefits (electronically). No new debt needs to be issued, correct? In fact, would not the US debt be reduced by the net amount of SSTF securities redeemed? The government liabilities would change in composition, from Treasuries to currency. I don’t believe this is equivalent to “monetizing the debt”, but I am not sure.

I realize that from an MMT perspective, the excess payroll tax is a reduction in aggregate demand (notably for specific income groups, because the tax stops at $95,000, those with lower incomes have their demand reduced by a higher percentage), and that the ability to pay retirees is dependent on the real capacity of the economy to support such beneficiaries. But from a government debt perspective, do I have the accounting correct?

First, the US government doesn’t “spend” the receipts from the bond sales. Bond sales are a monetary operation whereas spending is a fiscal operation. The fiscal operations are not revenue-constrained whereas they do impact on the monetary operations as described above. The central bank has to take into account the impact on bank reserves that arise from net public spending decisions.

Second, they typically offer debt via auction systems rather than a tap system. That is, they allow the private capital market to set the yield according to the level of demand for the debt issue. It is madness to do this but it reflects the ideological constraints that governments place on themselves.

Third, at the point of redemption there is a transfer of funds to you in return form rescinding the bond. This reduces government debt by that amount and increases bank reserves by the same amount. The bond is like a saving account and the bank reserves are like a non-interest bearing bank account (depending on the policy of reserve support adopted by the central bank).

Fourth, the government clearly doesn’t have to save anything to repay all its nominal debt (denominated in its own currency). In fact, the notion of a currency-issuing government saving in its own currency is nonsensical. Saving is an act performed by households who forego consumption now to provide for higher levels of consumption in the future. They have to sacrifice some consumption now because they are financially constrained.

For a national government, they never have to forego spending now to have the capacity to spend in the future – from a financial perspective. So saving is not a valid conception for a currency-issuing government.

With respect to the US Social Security Trust Fund, there are two components of total US public debt:

- The debt held by the public as a result of the “total net amount borrowed to cover the federal government’s accumulated budget deficits” – that is the government just borrows back what it spends. Sounds like a make work scheme for those who administer this system.

- The debt that is held in so-called government accounts which is “the total net amount of federal debt issued to specialized federal accounts, primarily trust funds (e.g., Social Security)”. Under US law, any surpluses that the trust fund has have to be invested in “special federal government securities”.

At the end of November 2009 about 36.3 per cent of total US public debt outstanding was held by intergovernment accounts. The US social security system set up during the Great Depression requires that specially identified payroll taxes be levied to help pay for social security. If there is an excess of revenue raised in any year it goes in to the Social Security Trust Fund which is the responsibility of the US Treasury.

Normally revenue exceeds payouts and the law requires that the surpluses are invested in “special series, non-marketable U.S. Government bonds” which mainstream economists take to mean that the payroll taxes (that is, the Social Security Trust Fund) “finance” US federal government net spending (deficit).

In fact, this is all smoke and mirrors. The Trust fund can be supplemented from the US government at any time they like (subject to legislation). The only time this has happened was in 1982 when according to the Annual Report the assets of the Trust Fund were close to being depleted and the US Congress allowed the Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund (OASI), which is the largest of the funds to borrow from elsewhere in the federal system.

The bottom line is that US federal government can always fund its social security obligations and any other nominal obligations that it faces. There is no need for these elaborate arrangements to “store up” spending capacity.

Certainly, from a transparency perspective, the public should know exactly where spending is going. But to think that having these “funds” will help governments “afford” commitments in the future is inapplicable to a fiat monetary system.

The whole public debt limit debate is exemplified in the regular US debate in relation to the solvency of the Social Security Trust Fund. The idea is that these accumulated surpluses allegedly stored away will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population is crazy.

The same lunacy pervades the so-called intergenerational (or aging society) debate. While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, MMT tells us that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

In a fiat monetary system, unless you impose voluntary financial constraints on the national government, such as we have discussed above, then the assumption is erroneous. Without these ridiculous constraints, the national government can spend up to what is offered for sale.

Further, the idea that “taxpayers’ funds” will be squeezed to repay debt or service the health needs of the future society is also nonsensical. MMT tells us that taxpayers do not fund “anything”. Taxes are paid by debiting accounts of the member commercial banks accounts whereas spending occurs by crediting the same.

The notion that these “debited funds” have some further use is not applicable to anything. When taxes are levied the revenue does not go anywhere. The flow of funds is accounted for, but accounting for a surplus that is merely a discretionary net contraction of private liquidity by government does not change the capacity of government to inject future liquidity at any time it chooses.

The standard mainstream intertemporal Government Budget Constraint analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is also problematic. The problem is that the GBC is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner.

Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures through the political system. Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain. Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When I say that there is no intrinsic financial constraint on federal government spending in a modern monetary system, I am not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit.

I have never advocated unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector. This may not coincide with full employment and so it is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that this equality occurs at full employment.

Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that net public spending is just enough to ensure that is it not inflationary (adding to much nominal demand in relation to the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) nor deflationary (not filling the spending gap left by non-government saving).

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light. If the federal government (anywhere) tries to run budget surpluses to keep public debt low then it will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

The goal should always be to maintain efficient and effective public services and full employment. Clearly the real public command on resources matters by which I mean the resources that are employed to deliver the public services. So real infrastructure and real know how etc define the essence of an effective provision of public goods. The actual deficit figure is irrelevant in making this assessment.

Finally, all of this is about political choices rather than government finances. The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

Any attempt to link the two via fiscal policy “discipline”, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term. The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such “discipline” reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results.

Clearly fiscal discipline may help maintain low inflation (or even induce deflation) because it acts as a deflationary force relying on sustained excess capacity and unemployment to keep prices under control. Fiscal discipline also reduces non-government savings and so undermines the capacity of households to manage their own life risks.

Question 15:

The classical textbook ‘crowding out’ argument you claim is false; you note that government deficits increase the reserves of banks and thus the overnight interest rate of banks actually goes down as a result, causing interest rates to fall rather than rise … … [in relation to an inflationary situation] … QUESTION 1: wouldn’t the Federal reserve respond to such inflationary government expenditure by raising interest rates (as part of its “anti-inflation” policy), thus crowding out private investment? There is the overnight interest rate, sure, but you seem to overlook the official interbank rate by the Reserve (which is discussed often in public and also influences planning and business expectations) hence crowding out investment due to inflationary pressures, albeit inadvertently. Keynes also anticipated the crowding out argument because as he notes in the General Theory government intervention could send bad signals to business which might delay further investment. As with the 1970s, we saw that transfer payments are more inflationary than public works (say Japan) as it is income in excess of output (i.e. there is no corresponding output to match the increase in transfer payments): so would you agree it depends on the TYPE of deficit being run by the government is important. Of course, in Japan government deficits weren’t going to cause a rise in interest given a low inflation rate. Furthermore, QUESTION 2: does it also depends on HOW government raises its deficit (of course, I understand that government’s put needless limits on themselves, but if it raises its deficit through bonds and borrowing rather than pure monetary expansion there might be some room for the ‘crowding out’ argument).

MMT does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on the mechanisms you have identified. They in fact assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and neither captures the causality you propose in Question 1. But MMT theory is totally consistent with a central bank that pushes rates up because it believes it should fight inflation and this policy damages aggregate demand.

The interbank rate is the rate at which banks lend to each other overnight to make reserve adjustments. This will fall to whatever support rate the central bank pays on reserves if there are excess reserves and rise to that rate if there is a shortage of reserves. The central bank aims to keep the interbank rate consistent with its policy rate and it does this via liquidity management (selling and buying bonds). But this doesn’t have any particular implications for the rate of inflation or the impact of central bank policy on aggregate demand as a response to a particular inflation rate.

It is unclear what is meant by the TYPE of deficit – but I assume it to be the composition of the net spending. Clearly a particular deficit outcome can have a greater or lesser impact on nominal aggregate demand depending on the multipliers that follow. So a tax cut is seen as being less expansionary (because some of it is saved) than an increase in public works spending. But there is debate about these different multipliers.

The important point is that the government has to manage its impact on nominal demand to ensure it doesn’t conflict with the real capacity of the economy to respond via output growth and this requirement (which is a vital component of fiscal sustainability) has to be balanced with the desired composition of the net spending position (to ensure other policy objectives are being achieved).

In terms of Question 2, this is the classic textbook debate – that the “financing” method determines how expansionary the spending is and how “inflationary” it will be. The overall debate is vacuous. The only thing that matters is the net impact of the spending.

But is is also true that a natinoal government that spends $X million and taxes nearly that much will add less to nominal demand than a government who spends $X million and doesn’t perform any other operations (tax changes or bond issues). All this tells you is that taxes are a vehicle to attenuate purchasing power in the non-government sector.

Question 16:

I’m a NYC high school student … you have made it very clear that the only true limit you see on government spending is inflation. But why isn’t it possible for there to be a currency crises in a country with debts denominated in that same currency? And on top of that why won’t an incredibly aggressive fiscal policy lead to imported inflation? Under MMT is there any justification for progressive taxation? In addition, is the only relevant tax income taxes? Also when governments sell bonds to cover deficits can’t deficits become counterproductive when yields on government bonds become so large that they become inflationary? Finally, perhaps my most burning question, won’t investors and players in financial markets see these incredible budget deficits and react like they are inflationary or indicative of a currency crisis even if they wouldn’t be and cause inflation self fulfilling expectations style?

Well that is another blog I think and all the questions are excellent. But here are some quick thoughts.

First, what exactly is a currency crisis in the context of all debts denominated in the same (I assume you mean domestic) currency? There is surely private credit risk – that is, debtors not being able to repay their debts. Mass insolvency could be source of major financial then real disruption. The sub-prime crisis is an example of this.

But there can never be a risk of sovereign debt insolvency if the debt is issued in the currency that the government issues. The government may choose for political reasons not to honour its debts. But it could never say it didn’t have enough “money” to pay its debts.

Second, it is possible, depending on the openness of the economy and the propensity to import for a strongly growing economy to push the trade position into deficit and with flexible exchange rates promote depreciation. The depreciation, by definition, means that the imported goods component of the price index will rise. Under some circumstances this may promote inflationary pressures. It is unlikely that the magnitude of this impact will be large. But an “incredibly aggressive” fiscal policy could generate this impact but it would be more likely to directly contribute to the price level via domestic purchases.

Third, taxation plays the role I outlined earlier in this blog. Progressive taxation depends on your values about who you want to have less purchasing power. MMT has nothing much to say about this although I personally (as an ideological position) consider progressive taxation to be important although I also think some regressive taxes are fine (if they promote simplicity – such as an across the board goods and services tax). The important point about progression which is often lost in the debate is that you have to judge the overall impact of the fiscal position before you can make conclusions.

So a regressive tax system could be more than offset by a very progressive spending strategy and the ultimate impact of the fiscal position would end up being progressive and therefore fulfilling the ideological goals that are usually espoused by those who support progressive taxation.

Fourth, there are all sorts of taxes which can be used and help to balance the policy goals with the economic need to avoid inflationary impact. I talked a bit about this in my last answer above.

Fifth, there is no evidence that yields on government bonds become so large that they become inflationary. There are decisions that have to be made by a national government on the contribution that interest payments on outstanding debt make to aggregate demand and the impacts that other components make. But the government can offset so-called “inflationary” impacts of its spending by taxation changes if that is considered desirable – that is, if they deem they want that level of public activity in the economy.

Sixth, MMT doesn’t use terms like “incredible budget deficits”. They are not incredible because they exist. That is, you have to believe them. But your point is, in part, correct. The private sector can influence the course of the economy based on how they feel about things. But what exactly are they going to do in this case? Are they going to bring spending forward to avoid having to pay higher prices in the future because they fear inflation (even if those fears are unfounded)? If so, then the deficit will soon shrink as the automatic stabilisers will work in the opposite direction.

What else might happen? A lot of so-called experts are saying the Chinese will sell their US dollar stocks. What will that do other than drive the price down and force them to take losses? Why would they be so stupid? Nothing the private sector can do will reduce the capacity of the national government to net spend.

If your particular question has not been answered please accept my apologies. I will make this a regular series and will get around to answering all questions I am sent. I have several more on my current list.

And finally, I receive E-mails that are like this one:

Comment:

Interested in receiving regular irreverent observations.

I hope these are regularly provided.

Anyway, the things that you do sitting on a train between Sydney and Newcastle.

That is enough for today!

Thanks Bill, great idea for a blog post. I’m going to forward this to friends who probably have similar questions.

I’d like to talk about an exchange I’ve had with another blogger to illustrate how much I feel I’ve learned over the last couple months. While I certainly have to get some things clearer in my mind one thing I think I have already taken home is the ideas of govts financing anything, or borrowing anything from any other source. This has given me the confidence to ask better questions and it has allowed me to truly expose the true twisted logic of so many debt a phobes. This was at Bruce Krastings site and he was continuing his assault on the US entitlements, which he started over on Angry Bear. This is probably where your Question #14 guy was referring to his exchange. Ironically he called his post “Thinking Outside the Box”

http://brucekrasting.blogspot.com/2010/01/following-discussion-is-effort-to.html

I did not read all the details of his post because I knew it was senseless, he was starting with the wrong assumption “Something needs to be done about SS its gonna have cash flow problems” but he made a reference to “borrowing from China” and this is where I posed my question to him.

I think his response is quite interesting. Keep in mind this guy “worked on Wall St for 25 yrs” and was an FX trader……so he KNOWS finance and currency issues. I posted as anonymous because at Angry Bear I accused him of being a deficit “terrorist” and he took exception to the remark, so I tried to be more gentle with my line of inquiry. It was his house after all. I’m not a TOTAL jerk.

Here is my first comment.

JANUARY 26, 2010 8:01 AM

Anonymous said…

Mr Krasting, Is “affording debt” even a relevant question when you are talking about a sovereign currency issuer? Why do you say things like “borrow money from China”? China has no money we need to borrow, we have all our own money. I hope you aren’t referring to renmibi because what the heck would we do with those?

JANUARY 26, 2010 11:41 AM

Bruce Krasting said…

Last I looked China had $750B of “our money” in their pocket. It is theirs. They can do with it what they wish. Including buying our debt. To that end I see us being dependent on them. I don’t like being dependent on anyone.

JANUARY 26, 2010 4:50 PM

Anonymous said…

If I sold you a car would you go around the next month and tell people I had YOUR money in my pocket? As I understand it China sold us stuff. We made a trade of goods for money which we thought was a good deal or we would not have done it. Now they have money with which they can buy something from us that we want to sell, either a treasury some debt or they can just buy some American goods. I dont see any of those scenarios as making us dependent. We do not NEED them to buy our debt, we ALLOW them because it benefits us. This line of rhetoric, which way too many in our political/economic circles choose to employ is not helpful. It is misleading and unnecessarily raises the concern level of many citizens. These are normal economic transactions which BOTH parties wish to do or they wouldnt do it. I would say if anything China is dependent on us to provide something they can spend their US$ on. We could tell them, nope go bury it in the ground, we aint got nothing for sale to YOU.

JANUARY 26, 2010 5:57 PM

Bruce Krasting said…

That is not how it works. Say China has our dollars. They need coal. The call up Australia and buy some coal. Then they convert our dollars into A$. Then they pay for the coal. China did not buy anything from us in this transaction. China does not have any obligation to either hold the dollars they have from exports to us. Nor do they have an obligation to buy our debt. Yes, they sell us crud and we send them dollars and they buy our debt with those dollars. But that does not have to be the result. What has happened in the past is not an assurance it will happen in the future. Like I said, I don’t want to be dependent on anyone.

JANUARY 26, 2010 10:19 PM

Anonymous said…

Seems to me the solution is to stop buying their stuff. Of course too many American corporations would not like this because they are getting rich using Chinese labor and selling us cheap goods. Too many US citizens like buying cheap stuff from Wal Mart . Its the only place they can afford to shop thanks to our neo liberal economic policies of the last three decades. I cant tell if you do or dont want us to sell them debt. In your first response to me you said : “Last I looked China had $750B of “our money” in their pocket. It is theirs. They can do with it what they wish. Including buying our debt. To that end I see us being dependent on them. I don’t like being dependent on anyone.” This sounds like you dont like China having the choice of buying our debt. In your last response your take was a little different: “Yes, they sell us crud and we send them dollars and they buy our debt with those dollars. But that does not have to be the result. What has happened in the past is not an assurance it will happen in the future. Like I said, I don’t want to be dependent on anyone.” You seemed here to not like the uncertainty of whether Chinas was going to purchase our debt. You want assurances that this will happen in the future. I think you are simply wanting to CONTROL China and dont like their independence. This is not a world the US controls any more. Get used to it and relax. The world wont end because China exercises their RIGHT to choose to do what they want with money they obtained through normal and completely consentual economic transactions. If they start holding guns to our head and taking stuff I will yell right along side you but this concern seems……………….. completely out of proportion to the reality of the situation.

JANUARY 27, 2010 3:08 AM

So now I want to see if my comments get removed. He seems to have tied himself in a knot. How can you not want them to buy debt and at the same time worry about assurances that they wont continue to buy debt. Maybe I’m missing something and if anyone here will point out what I’m missing I would appreciate it but this seems a perfect example of irrational fears trying to stoke irrational fears in everyone else.

Not sure why he took exception to the terrorist label, it seems to fit. ; )

Re Question 3: It seems to me that the universities are the places where some of the students begin to realise just how big the gap is between reality and the official line – just how much the universities tow the “party line” – a part of the prevailing power structure.

It reminds me very much of the way in which many young people who intend to enter the clergy are awakened when they enter the seminary or university theology classes. There is a wonderful video on this. It was taken at the Atheist Alliance International conference held last year in the US. The speaker is the great philosopher Dan Dennett. Go to Richard Dawkins website and access it and other highly interesting AAI talks at

http://richarddawkins.net/

Or go directly to the Dennett talk

http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p=D62809AD452EDB98

This year’s AAI conference will be held in Australia in March. I reckon we should have Bill giving a talk there with a topic something like “Breaking the Monetary Spell” or “The Money Delusion”!

Hi again bill, good post.

I have a question. You hold that the government should support the private sector in its desire to save by running the appropriate level of public debt.

However government liabilities are used as money by the private sector, so by increasing the government debt you are adding liquidity to the private sector, so would it make more sense to describe your position as follows:

‘the government should support the private sectors desire for liquidity’