I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Today started out well but then went downhill

Today started out well – early good waves at nearby Nobby’s Reef which kept things interesting. After that things progressively went down hill at least in terms of the things I read from the popular press. We had the EMU-rest of the world conflation to deal with. Then the public and private debt conflation. Then the austerity is good for us hypothesis. And by then I decided to read other things that were more interesting – like mysql technical manuals. Anyway, here is a report of my descent into gloom today.

At the outset, top item on my news feed this morning was the Bloomberg report that Moody’s claims the US and UK economies are moving “closer to losing” their “AAA Debt Rating”.

To which I thought so what. But then you read the story and you think that these characters must have something better to do with their lives than make up spurious “thresholds” and “ratios” etc then relentlessly issue press releases threatening the nations with mayhem, when at the end of it all, their sovereign debt ratings are largely irrelevant for governments which issue their own currency.

Perhaps we can send the bosses at Moody’s some retirement village brochures in places that have nice golf courses so they can just f*** off and leave everybody alone.

The London MD of Moody’s “sovereign risk” desk told Bloomberg (presumably using a voice full of self-importance) that the US and UK were “substantially closer to losing their AAA credit ratings as the cost of servicing their debt rose”.

So lets think about this. Both nations issue their own currency. They foolishly have falling into the conservative trap of handing out risk free government welfare annuities (bonds) to the financial markets that by them with the funds that the government itself has already spent.

Then non-government sector spending collapses, mostly because of the commercial incompetence of the financial markets aided and abetted by corrupt credit rating agency practices (ratings for dollars type criminality).

The governments in each nation, first of all, bail out the financial institutions so that the bosses and others can continue to get their exhorbitant and totally unjustifiable bonuses which pushes their net spending up. Then they hand out a little spending to underpin the real economy as unemployment starts to sharply rise. The support for the real economy is minimal and in the case of Britain they recessed for 6 quarters, a record.

The debt servicing payments increase because of the increase in the volume of outstanding debt given that monetary policy has rates at around zero and yields not much higher. These payments “come from no-where” given that each of the governments has an infinite financial capacity to credit bank accounts in the currency units they issue. The payments provide income to the non-government sector.

Where exactly is the problem?

Moody’s also said that under their “baseline scenario” – a term that is used to invoke some sense of science or technical rigour:

… the U.S. will spend more on debt service as a percentage of revenue this year than any other top-rated country except the U.K., and will be the biggest spender from 2011 to 2013 …

Yes, both are very large economies and both have been enduring a very significant real recession. So what?

Moody’s MD then was quoted as saying:

Under its adverse scenario, which assumes 0.5 percent lower growth each year, less fiscal adjustment and a stronger interest-rate shock, the U.S. will be paying about 15 percent of revenue in interest payments, more than the 14 percent limit that would lead to a downgrade to AA …

Other than yawn … you learn that after 14 per cent, the rating is downgraded to AA. What exactly is the financial and economic justification for that threshold? Why is 13 per cent AAA and 14.1 per cent AA? What materially happens to a nation when it crosses that threshold?

The answer to each of the questions is that this threshold is purely arbitrary The process of paying the interest does not change – the government just credits a relevant bank account with some keystrokes.

The government doesn’t lose its currency sovereignty once that threshold is passed. The real economy doesn’t fall in a heap after that threshold is passed. And there isn’t any scientifically credible evidence to show that inflation takes off after that threshold is passed.

But the overriding point is that there is no solvency risk in the first place. Please read my blogs – Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies and Ratings agencies and higher interest rates – for more discussion on this point.

Recall that in November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s made the first of a series of downgradings of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa (triple A) rating away. By December 2001, they further downgraded Japanese sovereign debt to Aa3 from Aa2. Then on May 31, 2002, they cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

So if you read this morning’s statement about the US and UK you will see that nothing has changed in the last 10 years – same nonsense.

At that time, the Japanese Finance Minister responded sensibly: “They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.” Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors. It also definitely helped Japan that they had such a strong domestic market for bonds.

And the Japanese government still has not trouble in this regard.

Rating sovereign debt according to default risk is nonsensical. While Japan’s economy was struggling at the time, the default risk on yen-denominated sovereign debt was nil given that the yen is a floating exchange rate.

The same is true of the US and UK today.

Of-course, Moody’s are not about to undertake a downgrade. They are talking at present that “distance-to- downgrade” has “substantially diminished”. They have some technical mumbo jumpo about a so called “debt reversibility band” which requires a nation to undertake fiscal austerity to get back into the “band”.

The sinister element is that Moody’s said:

Achieving the fiscal consolidation necessary to avert a downgrade will test “social cohesion” and may involve rewriting the “social contract” between governments and their people … People have to decide what level of pain they are willing to accept to have a healthy economy.

By which they mean, entrenched unemployment and rising poverty are required to satisfy Moody’s that the US and UK are within their “debt reversibility band”. And people actually believe this stuff.

The public debt ratio will fall again when growth resumes. Growth will not resume very strongly unless it is continued to be supported by discretionary fiscal stimulus. There is no magical alternative.

Private expectations are pessimistic and a consumption-led growth is the last thing we should be aiming for given the levels of household indebtedness around the Globe.

Public debt interest serving payments are nothing like the volume that might force the government to reduce other discretionary spending or increase taxes to take the heat off aggregate demand.

Anyway, that was the first story I read this morning. So you can see I should have stayed out in the line-up with the rest of the surf crew.

The debt theme continued, however – throughout the day in fact as new stories came in on my RSS feed.

I started reading – Batten down the hatches, the waters are still treacherous by Fairfax writer and known conservative Paul Sheehan (March 15, 2010) – with some hope given the title.

I thought that perhaps he was finally going to talk about the dangers of cutting back on the government spending support for economies around the world – I should have known better given the author.

His article those carried a point that is now resonating across deficit terrorist land and which is one of the worst errors of reasoning they make.

Sheehan said that with the talk last week of a booming Australian economy – (see my blog from last week – Its all booming down here folks!) – that:

… it appears we are springing back to normalcy without absorbing the reality: the global financial crisis is far from over. All the elements are in place for a second crash.

The world has become an economically unstable place, with enormous unresolved issues. Australia’s economy is fundamentally sound, but the global economy is fundamentally unsound. Even a good boat can be swamped by a bad sea and Australia, as a middling economy, will be buffeted by forces beyond its control unfolding in the United States, the European Community and Asia.

I somewhat agree with this perception although I think Australia’s economy which is increasingly reliant on environmentally unsustainable industries for its growth is not fundamentally sound. But that is the topic of another blog some day.

The point of agreement is that the there are major problems still in the World economy and the political processes are failing to address them. The band-aids have been applied – and then only sparingly so the wounds are still oozing – but the fundamental reform agenda is sinking under the pressure being mounted on governments by the conservative lobby groups.

The global leaders have not resolved the unsatisfactory practices of the banking sector and they have only begrudgingly provided fiscal support – while plotting a return to an emphasis on monetary policy with as little re-regulation as they can get away with.

So with a real estate market in the US still unwell, particularly the commercial segment; Europe basically a basket case, going down the tube because of a fundamentally flawed monetary system; and China now reporting it is struggling to maintain growth given its export markets remain weak – there is a lot to worry about in terms of the evolution of aggregate demand.

As Joseph Stiglitz said last week (March 7, 2010) in his UK Guardian article – Dangers of deficit-cut fetishism:

In America, for instance, bad debt and foreclosures are at levels not seen for three-quarters of a century; the decline in credit in 2009 was the largest since 1942 … even with large deficits, economic growth in the US and Europe is anemic, and forecasts of private-sector growth suggest that in the absence of continued government support, there is risk of continued stagnation – of growth too weak to return unemployment to normal levels anytime soon.

But Sheehan has another agenda. He is worried about the debt explosion (yes he used the word)! He said:

The International Monetary Fund estimates the world’s 20 largest economies, the G20, will have a combined debt equal to 118 per cent of their combined gross domestic product by 2014, meaning debt will have exploded by 50 per cent in just seven years. To fund what? In Australia, debt is being used for expansion of the mining sector, which is good, but also for the ill-disciplined spending of the Rudd government and the chronically overpriced housing sector. As a result, Australia’s economy is more vulnerable to economic stress from abroad.

So the first point to note is that he is equating the debt incurred in the currency of issue by the government of issue with private debt which is in Australia’s case is increasingly denominated in foreign currency units.

That conflation alone tells you that this journalist does not understand the subtleties of the subject matter he is prognosticating about. It is very clear that rising private debt ratios increase the risk of private insolvency. This is even more likely when the debt is denominated in a foreign currency.

It is also clear that a government that borrows in a foreign currency is also at risk of insolvency. Further, there is never a need for a government to borrow in a foreign currency. Some people will retort that a less developed nation would not get access to capital if it didn’t undertake foreign currency loans. My view is different.

If all the developing governments were committed to only spending in their own currencies then the first-world suppliers would face a major realisation crisis and would be forced to deal on the terms presented to them. Cartels are very effective structures for getting your own way!

In terms of the so-called “ill-disciplined spending of the Rudd government” he cannot be thinking in terms of the size of the fiscal intervention because that was by any standards insufficient to meet the private spending slowdown. What evidence is sufficient to establish my conclusion? GDP has slowed to well below trend growth and labour underutilisation is now about 4-5 per cent above what it was at the peak of the last growth cycle – and even then there was excessive slack in the labour market.

If he is talking about the design of the fiscal intervention then I have more sympathy. There was a scant amount of funds directed at job creation and too much directed at giving people cash to buy plasma TVs with. Further, the home insulation plan, while sensible in concept, was rushed and exposed the lack of regulation in the trades sector among other things.

At any rate, Sheehan then chooses to quote from an author from Sydney’s Centre of Independent Studies, which is an ultra free-market lobbying outfit that has zero credibility in terms of the research they pump out with the funding aid of corporate sector.

The quoted economist claims that:

The legacy of four consecutive years of inflated deficits will be a level of debt more than 50 per cent higher, as a proportion of GDP, than before the [financial] crisis, and nominal debt of almost $US10 trillion ($10.9 trillion) … debt burden higher than at any time since the early post-World War II years. The difference then was that debt was in steep decline; in the current episode, it is soaring to a new plateau from which there is no prospect of a steep decline … Worse, two-thirds of this increased debt is coming from increased spending by the Obama administration … the bigger the problem becomes because the cost of debt servicing is already beginning to snowball.

A snowball gets bigger and bigger as it rolls down the hill. As least that is my perception. I could be wrong given that I lived close to the coast all my life in generally warm conditions and have seen snow a few times.

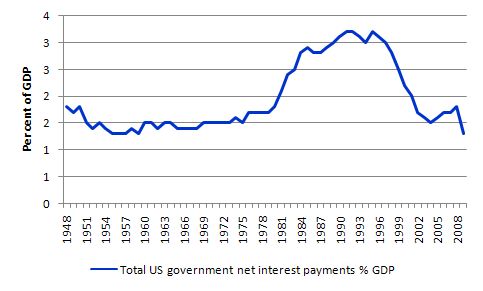

I had a look at some US data to check the snowball statement. First, from the US Office of Management and Budget I looked at the total US Federal government interest payments as a percentage of GDP. The following graph shows you what I found.

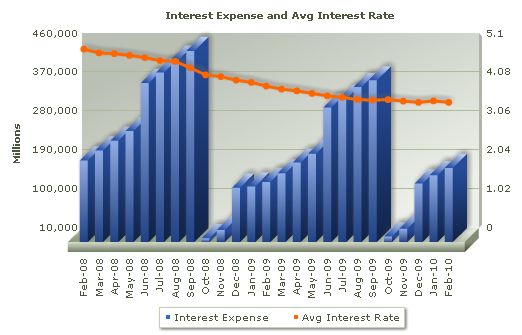

Then I consulted the Bureau of the Public Debt, which is a division of the US Department of the Treasury. I captured the following graph from their charting service.

So I don’t see any snowballs there.

Sheehan’s CIS economist then claimed that:

The current fiscal policies contain the seeds of the next global financial crisis with its epicentre in Washington rather than New York … The problem of excessive indebtedness is in the process of being transferred to the public sector. It is not clear how simply passing the problem between sectors can be a solution to anything.

Therein lies his idiocy. There is a huge difference between private and public debt. Please read my blog – Debt is not debt – for more discussion on this point.

While I think the conservative practice of issuing public debt should be stopped, the real focus is on what the net spending is achieving not the changes to the accounting balance sheets that are accompanying the spending. They only tell you to a cent that the public deficits are building increased nominal wealth in the private sector in the form of the increased bond holdings.

But the real attention should be on the underwriting of aggregate demand and the prevention of another depression. See below for further analysis of the benefits of the fiscal interventions.

This claim that overall leverage has to fall is now commonly rehearsed even by so-called progressives. It relies on a fallacious juxtaposition – the conflation of public and private debt and no progressive worth their while would engage in such reasoning.

We should actually applaud the transfer of private debt to the public sector. Given that it is being accomplished by the deficit spending which is “financing” the desire by the private sector to increase its saving ratio – the financing comes about through the deficits underwriting some economic growth which generates the increased income that allows the private sector to save.

If the private desire to save – which is clearly apparent and a reaction to the credit binge that preceded the crisis – had not have been accomodated by the rising deficits then the negative income adjustments would have been more severe than they were and the private sector’s plans to return some safety margin to their balance sheet positions would have been thwarted.

The only way the private sector can accomplish significant delegeraging is if economic growth is supported strongly by public deficits. Clearly this commentator has no idea of the macroeconomic linkages in this respect.

Sheehan then conflates Greece with the UK and we give up on him at that point.

While on the UK, known conservative economist Columbia University’s Jeffrey Sachs seems to be forgoing all academic credibility (he had none anyway) by teaming up with Britain’s shadow chancellor George Osborne in a piece published yesterday (March 14, 2010) by the Financial Times – A frugal policy is the better solution.

They began with the typical line:

Virtually all policy analysts agree that the path to renewed prosperity in Europe and the US depends on a credible plan to re-establish sound public finances.

So if you don’t agree you are a ratbag is the inference. I wear my ratbaggery with some pride let me tell you.

Anyway, in what follows, Osborne reveals he knows nothing about this stuff while Sachs, who should know better, must be playing some other game. How much are the Tories paying him to say these things?

They write:

Without such a plan, the travails which have hit Greece and which are threatening Portugal and Spain will soon enough threaten the UK, US, and other deficit-ridden countries. In the recent duel of macro-economists, one camp has called for early budget consolidation, followed by further measures over five years. We agree. Others want more fiscal stimulus, delaying deficit reduction. We believe delaying the start of deficit reduction would put long-term recovery at risk. Such an approach misjudges politics, financial markets, and underlying economic realities.

So once again we conflate non-sovereign nations (Greece, Portugal and Spain) with sovereign countries (UK and the US). That conflation immediately lets you know that there is nothing credible being said in this piece. Along the same lines of those who conflate private and sovereign debt.

As Stiglitz said last week:

Reducing government spending, especially in harder-hit economies like the UK, is a risk not worth taking at this point

But I noted that Osborne and Sachs talked about “politics, financial markets and underlying economic realities”.

They are critical of “lax financial regulations” in the lead up to the crisis. I agree with that but the article does not outline a comprehensive reform strategy. Rather it reinforces the Moody’s-type line that “financial markets are perfectly capable of getting spooked about the prospects of debt financing in the medium term” and can cause damage – and Greece is used as the example.

Greece was a sitting duck – bound by a monetary system where the financial market bullies could pick it off at will. As noted above, Japan showed the “markets” that they don’t rule at all. And on countries with non-sovereign monetary systems, Argentina really showed them.

They claim that economic theory undermines the view promoted by “Keynesians” that:

… delay is beneficial in the short term because it provokes more spending today – irrespective of future debt burdens … If the starting position is a large structural deficit, further fiscal “stimulus” can darken consumer and business confidence by creating fears about future debt burdens. These fears may be translated directly into higher borrowing costs today for government and the private economy. There are many well-studied examples of “negative fiscal multipliers”, in which credible fiscal retrenchments in fact stimulated the economy, via greater consumer and investor outlays, by reducing borrowing costs and spurring confidence.

All the well-known studies that eschew the use of fiscal policy are fraudulent in various ways – theoretical model that doesn’t stack up; faulty econometric techniques; poor datasets. The reasonable conclusion from the vast array of literature on the topic is that fiscal multipliers are positive, there is no Ricardian Equivalence effects operating, and a growing economy boosts consumer and investment sentiment.

It is hard to sit there view that fiscal cutbacks must be made immediately with their vision for the future. They say that the public sector should aim to deliver high quality “modern infrastructure, high-quality education, pre-commercial innovation, and a world-class science and technology base”.

They conclude that:

Our priority should be a medium-term fiscal framework, with the first steps starting this year. That must be matched by improvements in the delivery of health, education, skills, and technology; social protection for those in need; and a decent regard for the long-term investments needed to rebuild an economy crushed by the bubbles of wishful thinking.

Yes, I totally agree with all of that.. And the years of neo-liberal neglect of these essential public sector roles in almost every country one can think off has led to a severe degradation in these important areas of infrastructure – public infrastructure, health, education, transport and urban planning systems, renewable energy and all the rest of it.

But committing to that sort of vision will require substantial continuous deficits into the future even when the economies return to growth. The share of public activity in total real GDP will have to rise to ensure that these enhancements are effectively pursued. I don’t see any case for austerity in that sort of schema.

They claim that we have to avoid financial and property bubbles. I agree but that means less resources have to be made available to consumers and a significant recasting of the regulative environment for banks and financial markets. These requirements have nothing to do with austerity.

I agree with Stiglitz – austerity will just cause more damage and steer the debate away from base level reform.

He represents the alternative, more considered view of the current debate about fiscal policy. He said:

A wave of fiscal austerity is rushing over Europe and America. The magnitude of budget deficits – like the magnitude of the downturn – has taken many by surprise. But despite protests by yesterday’s proponents of deregulation, who would like the government to remain passive, most economists believe that government spending has made a difference, helping to avert another Great Depression.

Most economists also agree that it is a mistake to look at only one side of a balance sheet (whether for the public or private sector). One has to look not only at what a country or firm owes, but also at its assets. This should help answer those financial sector hawks who are raising alarms about government spending. After all, even deficit hawks acknowledge that we should be focusing not on today’s deficit, but on the long-term national debt. Spending, especially on investments in education, technology, and infrastructure, can actually lead to lower long-term deficits. Banks’ short-sightedness helped create the crisis; we cannot let government short-sightedness – prodded by the financial sector – prolong it.

I thought it was interesting that both Osborne/Sachs and Stiglitz were claiming that “most economists” agreed with their diametrically opposed view points.

But the message is clear – now is the time for governments to undertake some serious investment in renewable technology, in human capital augmentation, in building research capacity in our universities and that will require on-going deficits.

The public infrastructure base they are working with is severely diminished as a consequence of a few decades of relative austerity (pursuit of surpluses etc) and corporate welfare payments.

The other interesting point that Stiglitz makes which is well-known but worth repeating over and over again:

… the appropriate size of a deficit depends in part on the state of the economy. A weaker economy calls for a larger deficit, and the appropriate size of the deficit in the face of a recession depends on the precise circumstances … [and in terms of forecasting what will happen] … (t)he risks are asymmetric: if these forecasts are wrong, and there is a more robust recovery, then, of course, expenditures can be cut back and/or taxes increased. But if these forecasts are right, then a premature “exit” from deficit spending risks pushing the economy back into recession. This is one of the lessons we should have learned from America’s experience in the Great Depression; it is also one of the lessons to emerge from Japan’s experience in the late 1990s.

This is an understated point. While the politics may not be as easy as counting to 10, the government can more easily pull back a growing economy than it can rescusitate a seriously sick one. The Japanese experience is a lesson we should not forget (in all its dimensions).

Further, the upside risk is inflation while the downside risk is much more damaging – lost income, lost human and physical capital investment, human impoverishment, increased crimes, increased family breakdown, increased alcohol and substance abuse, increased mental illness incidence and more.

I am not advocating an inflationary growth strategy but that is the risk at high pressure. Economies are so far away from that risk zone at present and staring at all the downside risks which are much more costly both in the short- and long-run – that serious leadership should involve staring down the deficit terrorists and mounting political campaigns to starve them of “public oxygen”.

The problem is that governments everywhere are fuelling the frenzy and volunatarily offering premature fiscal austerity strategies which are exposing their citizens to all the downside risk.

It is totally irresponsible and the anathema of prudent and enlightened leadership.

Conclusion

First, you cannot compare public debt with private debt. Such a comparison is inapplicable. Further, if you really are committed to reductions in private debt levels (scaled by income) then, given the conservative arrangements about debt issuance, you will have to learn to tolerate higher public debt levels.

With that said, most of the statements made about public debt levels are pure fiction and reflect ignorance and ideology rather than substance.

Second, you cannot draw conclusions about different monetary systems as if they are the same. The EMU is a totally different monetary system to that which the UK or the US operates. All EMU governments face the risk of insolvency while the UK and US governments never face such a risk.

Third, if we really want to restructure national economies and reform financial markets etc, then the role that the public sector will have to play in infrastructure provision and regulation has to increase not decrease. That will necessitate on-going budget deficits. The terrorists will just have to get used to that.

Fourth, the downside risk involved in engaging in fiscal austerity is far more damaging than the risks of overheating the economy by some degree.

That is enough for today!

Seems to me that the really relevant ratio is that between a politician’s total campaign contributions and special interest contributions. I saw in this morning’s paper that Iowa Senator Charles Grassley received 22% of his total contributions from the health insurance industry. He took over 2 million dollars from this interest group while was playing a pivotal role in health care legislation and, surprise, pushed legislation favorable to the industry, not his constituents or the nation.

I was instructed to come to your site from another commenter at NC and learn how printing money as the US is doing is not inflationary.

I guess I was taught long ago that if you expand the money supply then there is more money chasing the same amount of goods and services and therefore is reduced purchasing value of currency. Call it inflation/deflation whatever. How does one say that this is not the end result of printing money as the US is doing?

Please and thank you. I am a regular and respectful reader of your site and agree with much of what you say but we have a different view of the threads of history and the future at times.

Dear psychohistorian,

In the Quantity Theory of Money classical economists held the q and v components of the mv = pq equation so a change in base money was necessarily resulted in changes to the price level. However, there is ample evidence showing that neither the velocity of money (v) or output (q) is fixed. When the economy is recessed individuals tend to save more than before so v goes down. Likewise, during tough economic times production is cut do to declining demand. The classical economists just assume markets are self-regulating and will always revert back to an equilibrium state where v and q are held constant. If this assumption is not true then there is no reason to think that increasing the monetary base (m) must lead to a higher price level (inflation). For more a more detailed explanation of this line of reasoning I recommend this blog post (search for the phrase “Quantity Theory of Money,”):

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=7838

Also of interest might be the blog post “Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101,” as it deals specifically with inflation fears:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=3773

Hope that helps

Bill-

I am an avid (novice) consumer of your writings (also of Wray, Mosler, Auerback, et al) while endeavoring to understand them and their implications.

May I ask a few dumb Qs?

Is public debt equal to public deficit?

Must these deficits be financed with debt instruments?

What happens if the deficit was left to stand without issuing bonds/notes?

As an interested layman I have question about especially the external balance. Does it make practical difference about external surplus if e.g. a country like Norway where the oil is an asset belonging to the people and I suppose the surplus is in government control versus a more normal situation where the export sector is privately owned?

Ill guess it also in practice makes a difference if the source of external balance is easily achieved by extracting a natural resource versus industry that have real competition and continuing innovation is needed to stay ahead.

As I see it both in Sweden and Germany they do squeeze the internal consumption by “restrain” I wage increase and fairly high consumption taxes to achieve external surplus. I such a case does it add a negative effect to total wellbeing of the national economy?

In Sweden both right and left is obsessed with public “saving”. There is a goal to have a surplus in public sector over a business cycle of 1%, recently changed from 2% and had earlier been criticized by right wing parties to not be enough they wanted both 3 and 4%. Why right wingers wanted the private sector to be “robbed” by the public sector I failed to understand, one could thought that they by principle that money primarily should be in the private sector.

In the 2006 election the right wingers did prevail and ended 12 years of social democrats in power. They have succeeded to achieve substantial saving and had managed a 440 billion accumulated financial surplus 2006 that was 650 billion. This was then estimated to be close to trillion 2010. Even if it is Swedish crowns it is substantial money. A graph of public sector balance from 2001 -> with estimates for 2010 and 2011.

In 2006 there was one study that found that the accumulated neglected need for maintenance and updating of public infrastructure landed on the roughly 400 billon. Now I don’t know what was included but it is on per capita basis eight times what some American engineer association have estimated the neglected need for maintenance and updating of American road, bridges and so on. Of course such estimates have to be taken with a grain of salt, usually made by organizations that have a stake in it.

One of the biggest issues for the social democrat opposition this election year is the budget deficit, how irresponsible the government are giving tax cut to the rich on borrowed money. So far we “only” have official unemployment figures at 9,4% but with a tradition to be very good at recategorize out of official unemployment figures, the right wingers could actually beat the left from the left 2006 on unemployment issues and alienation from the labor market. But also the governing right wingers promise that the public sector will be in surplus again in no time, at least to 2013.

We have had a substantial export surplus since 1993, probably the main component of growth in GDP. Despite it was export export sector who take the main hit in 2009 crisis the percent ratio stayed on top. Net exp-imp/GDP 93-09, net exp-imp constant prices 93-09. After more than one and a half decade of macroeconomic variables in frequent public debate, especially export and trade balance there is almost never mention since the 90s crisis, most Swedes have not the faintest idea that there is a constant high trade surplus, most probably is of the idea that we are losers on the global market and if only we exported more everything would be so much better, roads and schools and so on wouldn’t decay.

When the crisis unemployment is the topic the present government usually counter that at least we have low deficit despite severe international crisis and the left opposition doesn’t counter arguing that, one of their main opposition team is the irresponsible deficit/borrowing.

How should one judge this national economy approach?

What effect would it have to running a larger or prolonged public deficit to restore employment, while the central bank law say that government is not allowed to use Central Bank facility to finance deficit and have to borrow what it need on the market?

There is sometimes strange language here, after the mismanaged crisis of the early 90s the public balance sheet did go negative more debts than financial assets, by harsh austerity measures and a booming export sector riding the international boom they turned it to surplus in around 1996/97, albeit the domestic market had hardly any growth. This surplus was then named in the official accounting a negative debt. Is this standard practice?

The export sector have very good productivity growth and produce more and more with declining employees. A few years ago GM did arrange a contest between its Saab factory in Sweden and Opel in Russelsheim German for a new line of cars, of course it was a face contest the production line was aimed for Russelsheim where the have a EU subsidized new factor and European design centre, it didn’t matter that gross labor cost was 30% higher in Germany. I don’t know for sure but I guess that lobor cost to put together a car is in the range of 10-20% of total cost.

I hope it’s understandable then I have not very much English education, and should have but haven’t looked over the post a few more times and shortened to at least a third.

/Lars

Well, my day started in the toilet: I just finished reading first 3 volumes of the Lehman bankruptcy examiners report when I read an Associated Press article trying to start a panic over the fact that Social Security Administration is starting to cash in the treasury IOUs it holds. I could not believe what I was reading either this was a case of a) corporate owned media helping out Wall Street, b) writers/editors absolutely clueless of gov’t accounting and economics or c) both a & b. Amazing.

Rebel, it smells to me like a plot in the works. “They” are throwing it into the echo chamber to create a meme out of it. SOP.

Yes, it is outrageous. But everything is outrageous these days. It seems that the liars are trying to top each other with yet a bigger one. I’m never sure these days whether I’m reading “the news” or The Onion.

Dear Bill,

Two points. First, the ratio of public to private debt or the ratio between external to internal debt, can be useful to see who has taken the burden of debt and who receives the income from it, especially in a case of involuntary constrained fiscal policy. For example, in the case of Greece, where the ratio is much greater than one, it reflects the high degree of tax evasion and the savings preference of Greeks, although a lot of the debt is owned by foreign banks.. Even in a case of voluntary constrained discretionary policy, “captured” by rating agencies, politicians and speculators, ithe ratios are important to show the extent of excessive leverage of private speculative finance that can lead to a crisis. I have written about this case of “capture” of discretionary policy in acomment at your previous blog.

psycho (somehow shortening it seems wrong)…….psychohistorian

Welcome to the best econ blog on the web. Your concern is one that most everyone has, liberal or conservative, progressive or neanderthal. We’ve all been programmed to think “devaluing currency means inflation”. This is the standard gold bug view of what it means to be able to measure a currencies worth. If you have x amount of gold and y amount of dollars against that gold, increasing to 2y dollars with no concomitant increase in gold means prices will effectively double. Another way of saying that is if you originally get an exchange of 1oz of gold for every 20$ you hold and then the exchange rate is changed to 35$ per oz you have inflated your dollar by almost twice (this is exactly what Roosevelt did) Did this cause inflation? Did we see a rise in real prices at that time? I dont think so. In fact, many conservative economists have argued that in real terms, most people were better off because of the deflation. They have used this as a way to dismiss the Keynesians/Minskyians critique of defalationary spirals.

Now this certainly does not make this an open and shut case but it certainly should give pause to anyone trying to assert a simple “currency devaluation” theory of inflation. Of course in todays floating exchange rate monetary system, currency devaluation doesnt mean the same thing any way. The question needs to be asked devalued relative to what?

I think the more you read this blog and some of Mr Wrays, Mr Moslers and Mr Auerbachs work you might start to have a different view of currency in todays world.

Two quotes come to mind for me that have rattled around in my head; Warren Mosler said that “currency is not an investment it is a policy tool, something which investments are priced in” Mr Auerbach said “In these economic times there is going to be strain somewhere, let the strain be on the currency and not on the people” Putting currency in this light as something to shape policy and absorb economic strains is quite helpful and opens new avenues for getting through this crisis without putting any more people into poverty.

Bill –

Though it is true that nations with their own currency don’t face the default risk that Eurozone countries do, they do have the risk of hyperinflation which is almost as bad.

Now before we go any further, let me make one thing clear. I have as much contempt for Austrian School economists as you do. And I don’t think hyperinflation’s a likely outcome, just as I don’t think eurozone countries defaulting is a likely outcome. But if they followed your advice and ignored the need to get back into surplus, the pound could well sink below the Australian dollar!

Printing more money (even when loaned rather than literal) is one thing that causes the value of the currency to go down. And if people believe the currency will continue to decline in value, they will sell them and buy a more stable currency. And if businesses think a decline in value is likely, there will be a carry trade – after all, why would a local business borrow in Australian dollars when they can borrow in pounds at what amounts to a negative interest rate?

Right now the pound is buoyed by the expectation that Osborne will become chancellor and will have “a credible plan to re-establish sound public finances”.

Of course how he does so is a different matter entirely, and there are worrying signs that he’s putting too much emphasis on cuts. My own view is that the best strategy involves a massive surge in infrastructure spending (partly funded from 10yearish bonds in Euros and US dollars to stop the pound from sinking further) to offset the effects of cuts in other areas, and that university funding should be increased not cut, as going to university is the most productive thing many people can do right now.

Re Lars and Sweden: Bill, I know you are busy, but if you had time it would be very interesting to have your MMT analysis of the Swedish economy. Sweden is still occasionally cited as an example of a country with good social programmes and perhaps a quasi social democratic model to follow. But here Lars notes it has an unemployment rate of 9.4% and deteriorating infrastructure, hardly a shining example, and right and left parties compete to run budget surpluses. Sounds like confusion and not something to emulate at all.

I continue to love your blog. Thanks.

Comment to Lars: Thanks for the information on Sweden. You did fine with your English.

Aidan:

You need to do some historical research on hyperinflation to see that the money print is an effect, not a cause – a mismanaged economy in crisis cannot meet demand, regardless of how much or how little currency is in circulation.

It is easy to look at a prescription – say, take some pills – and jump to a scenario that once we swallow the whole bottle at once it will kill us or at least make us addicts. Yes, currency is a powerful tool and needs to be managed – the point being made at places like this is that it is traditional thinking that is grossly mismanaging the currency.

With regard to your carry trade example, actually the opposite occurred with Japan. The yen was seen to be a undervalued currency (deliberately driven down to boost imports) with a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), creating and environment you could borrow in yen and invest in something like AUD and enjoy a “risk free” return. Great as long as exchange rates stay stable and you are nimble. Anyone long the Euro the last two months that exchange rate volatility trumps low interest rates (and, say isn’t the Euro one of those neo-liberal managed currencies?)

As far as the UK cutting spending, remember that everyone thought that Reagan was going to cut the deficit in the 80s to restore the US dollar “value”, after all that’s what he promised. He ended up running the biggest deficits in US history at the time – and no one cared because the markets boomed.

Don’t worry about “funding” government spending. The bonds are purchased with the money spent – it sounds daft, but there’s the bond markets for you.

re:Greg. Isn’t it correct to say that floating currencies are being devalued relative to hard assets (e.g. gold)? In a world where everyone is trying to devalue their currencies to follow a policy of export led growth then gold should be the beneficiary. Gold has historically done well in times of inflation (70s) and deflation (30s) so is not just an indicator of impending inflation. In any case, there is a difference between goods inflation and asset price inflation. General inflation has been steadily falling since the early 80s (at the expense of unemployment as Bill and others show), but there have been plenty of asset price bubbles in the meantime…

Thank you for the kind words.

The export-import numbers is the one that is in GDP.

Another Swedish issue that comes to mind in these times when Greece is accused of fraudulent national accounting is that Sweden in the 70s did have fraudulent national accounting of a kind that was unpresented in the industrialized world, not even third world countries as Gabon an Zaire that then have had irregularities did have of the same size.

These fraudulent numbers was and has been the basic tool to wring the country from a democratic economic order to the neo-liberal path. Current account balance, external debt and something that is named companies/industries operating surplus in direct translation, i.e. gross profit minus real capital wear and tear (?).

Current account balance deficit was exaggerated with 400 %, and that was way beyond what was common levels among other similar countries in times of oil price peaks and global recession. The “operating surplus” was 300% higher than was said, this in the recession years of 75-78. But what really scared the shit out of people was the enormous foreign debt, many people to this day still believe that we is in huge debt to foreigners and that it was a public sector debt. State monopoly Public Service use to have graphic images of a new-born with a huge pile of money illustrating the debt he/she inherited. Some +60 billion, much money in those days.

The exaggerated current account deficit was created by huge omissions of service sector export, corrected ours deficit was in line with other oil dependent industry countries and even slightly better. In the numbers of foreign debt it was gross debt and flip side was not taking in to account, or if it was the counter balancing real values was down played. The main debtor was private sector i.e. industry operating on the international market that expanded its enterprise abroad, and just with a conservative and prudent market valuation of what they have built and acquired abroad the debt was gone and there was even a minor surplus.

This has probably never been rectified if it wasn’t for one economist hero (rare breed?) that did take the fight against the collective Swedish establishment. 1982 our national accounting got rectified on a scale that never have been seen in an industrial country. The economist hero did win the fight but lost the battle, a row of devaluations and austerity measures had already taken its toll. He was (of course) already before the final victory declared person non grata in the small close knit inbreeded Swedish establishment. This big rectifying of our national accounting couldn’t be completely overlooked in media, it was mentioned and a few articles were written. But then quickly buried and debate on economic issues soon carried on as no correction never had been done, until this day the image of the seventies is presented as such.

houseman

The thing I cant resolve in my mind is how can you say that gold is worth more than dollars when the only way to denote golds worth is IN dollars. That seems like a paradox to me. Gold cannot be more valuable than something which is necessary to denote its worth. What is golds worth without dollars? Saying that more or less people want gold necessitates saying why they want it. Most will say because its RISING in dollar value, which is another way of saying gold gives them access to more dollars.

So do they really want more dollars?

I am not sure you understand what rating agencies do. Ratings are ordinal assessment of government default risk. They are not in any way whatever concerned with the health of the overall economy, they focus on the narrow issue of whether the creditors are likely to get their money. As much as we’d like to impose a wider role on the raters, assessing all other economic issues is not their job.

So, their announcement needs to be read in thsi light. The simple reality is that because of their increasing debt level the US and the UK have moved done the ordinal rank list, relative to other countries, which as still solidly Aaa (Australia, say). In order to improve their debt position, some recalibatrion of what Moody’s term ‘social contract’ may indeed be required. That may not eb the right thing to do but then the creditors’ position is less strong.

Ilya, the problem here is basic stupidity on the part of the rating agencies.

Governments obtain funding at the risk-free rate for medium duration debt. That is typically 1-2% less than the growth rate of GDP, which is the growth rate of tax revenue.

So governments are, by definition, entities whose revenue growth rates exceed their cost of borrowing. They cannot default on sovereign denominated debt. They may be forced to default if they own debt in a foreign currency, and there is a currency crisis that causes the (foreign) interest rates to grow faster than their own economy. But that is the only way that they could default.

A business, on the other hand, is in a different position. It cannot obtain funding at the risk-free rate, and must obtain funding at a higher rate. Moreover a business cannot tax the general economy — so there is a risk that the economy will grow faster than the revenues of the business. In that case, the business may default. Sovereign governments have no such risk. That is why Japan, with it’s junk bond status, is in no danger of default, and is able to obtain funding with an average interest burden of 50 basis points. Its mathematically impossible for tax-receipts to grow more slowly than the risk-free rate in such a way as to force the debt service burden to increase over a long time period.

The Debt to GDP ratio could be 700%, and it doesn’t matter. The day Japan says “enough”, we will stabilize our deficit/GDP ratio, is the day that the Debt to GDP ratio will begin to fall and there is never any need to run a surplus to “pay off” risk-free debt.

That is the magic of having your cost of funds be 1-2% lower than your revenue growth rate, and if Moody’s understood this basic arithmetic, they would focus more on not lying to the public about CDO default rates, and less on trying to assess default risks for risk-free interest rates.

RSJ,

(a) first of all, none of that invalidates the basic premise that some countries are less credit-worthy than others. Rating agencies do not assess a country’s position vis-a-vis specific currency of issuance but do so in general terms. Should the US issue debt in Euros tomorrow, what would its creditworthiness be? That is what Moody’s is addressing and there is nothing stupid or criminal about that.

(b) countries do not default because of rational economic reasons. They default because the political solution to temporary economic problems is in may instances default. Otherwise, no one would ever default, internally or extenally, rather they would raise taxes. This is Moody’s ‘social contract’ point and indeed the US will need to decide between default on debt and default on pension and health liabilities. Your assumption is they will default on health.

(c) your analysis omits multiple instances of internal default through history. It mainly happens through re-nomination of the currency but it does happen.

(d) what happens when revenue growth temporarily collapses whilst funding costs remain what they are (since the debt needs to be serviced)?

I’m not aware of a default by a fiat currency issuing nation on sovereign-denominated debt.

The point about the tax burden is the point I was making. You can cut the Debt to GDP ratio by doing nothing. You don’t need to run surpluses or raise taxes. Just stop increasing the Deficit to GDP ratio, and the debt to GDP ratio will start to fall.

That is the benefit of having your cost of funds be less than your revenue growth rate. You can always grow your way out of any debt burden without any pain. Patience is enough. There is never any need for “sacrifice” — except of the self-imposed irrational variety.

Tax collections are volatile, and most of the growth in debt is due to declining revenues during the bust part of the boom/bust cycle. But it’s a cycle, so over the long term it doesn’t matter.

Sovereign fiat debt burdens are best completely ignored. The real issue is what is happening to the economy. If your deficits are too high, you may overheat, and by fiscal deficit spending, you are granting annuities to the private sector which may have consequences for income distribution.

But debt burdens are always a non-issue when your revenues grow faster than the rate of interest, and in any case the sale or repurchase of government debt has no consequence to the private sector as a whole. The actual deficit spending is what matters for the economy, and the debt takes care of itself behind the scenes, tucked away behind MZM as a non-entity for anyone outside of banks and other financial entities that need safe assets to lever up against.

This is completely different than the situation for households or businesses in the private sector, who must pay careful attention to their own debts, but then the ratings agencies should be smart enough to understand this, at least if they are paying professionals to treat these questions seriously.

On the other hand, they could also create a department that monitors the likelihood of Jupiter colliding into Saturn. Then they could come up with some fancy guidelines and issue “ratings” and occasional warnings about the likelihood increasing or decreasing based on what happens in some asteroid belt. Meanwhile, they rubberstamp synthetic bonds backed by subordinated tranches of Philippine mortgages as AAA, and give AIG a golden credit rating. I think Enron was still AAA when the stock was trading at a nickel.

Enron was never AAA. Neither are subordinated mortgage bonds, in the Phillippines or anywhere else. Neither was AIG. No need for sniping. Raters are serious people, whatever their mistakes or your opinion of them.

My parents would point out, the Sovier Union went through a couple of internal defaults. You issue domestic bonds to the population and then reissue the currency (and e.g. set a limit on how much of old money can exchange into the new currency) and wipe out people’s savings. Reinhart and Rogoff have other examples, including in democracies.

‘Over the long term it doesn’t matter’. Even accepting this, in the short term you run the risk of default. It is not the country defaulting, but the government. In the absurd extreme the interest bill is 100% of GDP. Future GDP growth – and therefore revenue collections – may outstrip future rises in the interest bill but you are cactus before you get there. So, you have to print money or raise taxes in the mean time. Both are a sort of default, of course, and involve a political trade off: precisely the point made by Moody’s.

Where am I going wrong?

‘A non-entity for anyone outside of banks and other financial entities’. This assumes the economy runs separately from finance. Not true.

See also http://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt0309f.pdf which explains that domestic currency ratings are higher than foreign currency debt ones. This says there’s been five domestic defaults since 1980. Not sure whether in all cases the currency was pegged or not, but in at least one, it was not.

russia is the only country to default on debt denominated in it’s currency without a currency peg. rogoff and reinhart’s analysis almost never touches on sovereign governments with floating exchange rates aka the modern economic situation (excluding eurozone plus a few others). i really regret reading their book. revenue’s collapsing reperesents a collapse in spending by the private sector so “printing money” to cover this deficit would hardly create inflation or involve a stripping of wealth from bondholders.

lets take a very simple economy. private sector spending yesterday was 100 dollars, sector A’s income was 100 dollars and sector B’s income was 0 dollars and both are at full employment of labor and resources. transactions between sectors constitute one day in this fictional economy. public sector spending is 100 dollars (in the form of a transfer paymen[not counted as income for tax purposes] to the last sector taxed) at midnight and sectoral income taxes are 100 percent of that day’s income at 11 pm . sector a has gotten the 100 dollars but has not spent anything so far.

let’s say the sector a saves 10 dollars (moving it’s propensity to consume from 100% to 90%) and only buy’s 90 dollars of output from sector b. now sector b has income of 90 which is taxed away. if the government decides to keep a balanced budget then sector b will have 90 dollars of income which it uses to purchase output(but only 90 % of potential output) from sector a. sector a the next day will only spend 81 dollars purchasing even less output from sector b (maintaining the same propensity to consume) and the government will only spend 81 dollars the next day. sector b the next day spends all of it’s income but purchases even less output from sector a. sector a spends 72.9 dollars purchasing even less sector b output and so on and so on.

on the other hand maintaining spending to offset the so called “leakages” will keep income’s at the same level. if the government decides to spend 100 dollars when it only recieves 90 in revenues it will satisfy the desire of sector a to save and keep the economy at the full employment of resources and perserve the incomes from days before.

besides all this i agree that government default is highly political but i would say that the rating agencies do not measure possible default by political reality but by their muddled understanding of what they believe to be economic reality.

So the rating agencies do not measure economic likelihood of default, but they do measure the political likelihood? I feel that the corrupt and venal agencies are surely even less well suited to this! They have no business opining on soveriegn credit risk.

Ilya, the only non-pegged currency nation there was Russia. It was unable to collect taxes due to mass corruption and tax-avoidance. During that time, about half tax revenue of the central government came from the city of moscow — in that type of a non-functioning government, all bets are off.

I am assuming a functioning government that is able to collect a fixed proportion of NGDP for taxes, over the long term. Even corrupt latin american nations are able to do this, and modern industrial economies certainly can. Obviously we are not talking about Russia here.

All other nations were on a pegged currency regime, and the defaults occurred during the latin american debt crisis in which high interest rates in the U.S. made it impossible for those regimes to roll-over dollar denominated debts, and to maintain the pegs. In that case, you can drop the peg and not default, or keep the peg and default. In both cases, the government is not sovereign in it’s currency, even if some of the debt is denominated in its own currency.

If interest payments are 100% of NGDP — which wouldn’t really happen barring a total collapse in GDP — then you can still roll the debt over. You do not “pay” the interest, you keep rolling it over. In general, anytime you have a fraction in which the numerator grows at a slower rate than the denominator, then the fraction will decline over time if primary deficits are capped. The denominator is NGDP and the numerator is nominal debt. I agree that if interest payments are that high, then the situation becomes more risky and sentiment can take a toll.

And inflation is not a default event for bonds. It merely means that the market has mispriced NGDP growth when it bought the bond. Everyone has to worry about inflation, of course, and the government is not the main driver of causing it, as we live in a world of endogenous money. Banks are typically the ones responsible for inflations and deflations, although this is very complex.

AIG had AAA, which is why it was able to hold naked positions. Enron was investment grade and kept its investment grade rating until a week before it declared bankruptcy.

Indeed there were junk Filipino CDOs created by Frank Partnoy at Morgan Stanley, and these were rated AAA. They were not backed by residential mortgages but the debt of various third world utility companies. They were called “FP” for Filipino Power, but really Frank Portnoy 🙂

Ilya: Bill’s discussed Russia (and others) here . . . https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=8322

RSJ: Very well said!

Best,

Scott

Dear Ilya and RSJ

In fact, the Russians were running there currency in a narrow band against the USD. The CBR lost billions of USD in the lead up to the default trying to defend the currency. Then the IMF came along and gave them advice.

They defaulted soon after on all debts including rouble-denominated debts. They definitely couldn’t pay the former but always could pay the latter.

best wishes

bill

pebird –

You can say everything is an effect because it has a cause. But when has hyperinflation ever happened without a huge increase in money supply?

You refer to “a mismanaged economy in crisis” seemingly oblivious to the fact that Britain has one of those! I’m glad you at least realise currency manipulation is a powerful tool, because Bill doesn’t seem to!

Jeffrey Sachs, in his book The End Of Poverty, writes of the hyperinflation that occurred in Bolivia when it took advantage of its currency sovereignty and kept lending itself money. He had a solution: raise taxes and cut spending enough to balance the budget immediately. It worked. And aside from the criticism that they should have raised taxes more to avoid making such big spending cuts, I’ve not heard anyone propose an alternative solution that would have been anywhere near as effective.

But I’d rather it not come to that in Britain!

Japan was different. Its strong balance of trade meant the ¥ kept appreciating in value. If that was happening to the £, there wouldn’t be a problem. But the opposite is occurring: balance of trade remains negative despite the sinking pound. So just creating and spending more pounds as Bill seems to advocate would risk Bolivia-style hyperinflation. Getting out of it would be much worse than avoiding it.

Dear Adam

I don’t know how much you know about Bolivia in the 1980s but Sachs doesn’t provide the full picture in his book and if your knowledge is limited to his presentation then you will not have a full appreciation of the events that led up to the hyperinflation. The true story is very different to the type of associations that you want the readers of this blog to tune into.

I spent some time studying this issue in the past and from my notes this is a summary.

Sachs makes out that this was just a demand-side inflation which went out of control but that is to ignore the historical circumstances. You have to understand the role that the foreign debt servicing payments played and the internal distributional conflict between labour and capital.

At the time of the hyperinflation, Bolivia’s economy was very narrowly composed. Its non-traded goods sector was dominated by the service sector (35 per cent); the public sector (11 per cent); manufacturing (about 15 per cent), and agriculture (19 per cent). It had a tiny export sector dominated by mining and oil.

When mining commodity prices fell in the early 1980s, GDP collapsed (prior to the inflation really taking off). The budget deficit grew because the revenue from the largely publicly-owned mines collapsed.

Further, the government also – foolishly – had substantial public debt liabilities denominated in foreign currencies. With the export collapse, the exchange rate fell which caused a fiscal crisis – difficulty in servicing the debt. As a result the government sold more debt to the central bank to allow it to continue paying local currency obligations.

The inflationary pressures were mostly sourced by exchange rate movements and the strain that these placed on international reserves and public revenue.

There was also significant politicial instability in Bolivia at that time with a coup in 1980 basically installing a military regime that was closly aligned with the booming elicit drug trade. This was short-lived and a puppet government emerged to assuage the complaints from foreign governments. Further, at that time, there was very significant capital flight and a huge drop in tin prices on world markets. These further strained foreign reserve holdings.

GDP dropped in 1982 by more than 5 per cent and the automatic stabilisers pushed tax revenue down and income support measures up. The ensuing conflict between workers and the capitalists over distributional share etc was also a key pressure on the price level.

By just correlating the monetary growth with the inflation rate doesn’t help to explain it especially if you ignore the significance of the contribtuion to the changes in the monetary base of the loss of net international reserves.

There are also many studies that show that the causality went the other way – so that the monetary growth chased price level acceleration not the other way around. The argument is that political factors constrain the government which tries to maintain real levels of spending and inflation continually erodes the real value of the tax revenue. So net spending in nominal terms rises and the growth in high powered money increases.

There is also a lot of research showing that in Bolivia at the time, it was the exchange rate that pushed the price level acceleration along which then pushed the growth in the monetary base. Detailed analysis of leads and lags between the variables confirms that in Bolivia’s case.

This is a far cry from the situation facing the UK at the moment. For a start the British government has virtually no foreign currency-denominated debt exposure.

Are you trying to argue that there is no scope for real output increases or rising employment in Britain as of this day?

Jumping to a conclusion based on some simple correlation between the growth in the monetary base and inflation in Bolivia will lead you into the morass of faulty inference.

best wishes

bill

Bill –

Sachs did mention most of that, though IIRC not the foreign currency debts. Nor did he mention the coup, though he did mention that there was an election between when he was first contacted and when he helped fix the problem.

Of course the hyperinflation was exchange rate driven – it always is! And printing more money is one thing that causes the exchange rate to devalue. I thought you understood the difference between, and links between, the three different kinds of inflation?

This does not mean I’m always opposed to printing more money – in fact where currencies are rising I regard it as the most sensible way of slowing it. But when currencies are falling it is generally something to avoid.

I’m certainly not “jumping to a conclusion based on some simple correlation between the growth in the monetary base and inflation in Bolivia”. The monetary base isn’t the problem, the plunging currency value is. And I’m not equating Britain’s current situation with Bolivia’s historical situation. I know things were much worse in Bolivia. Having said that, I can see many similarities. Just look at Britain today:

Economy dominated by the service sector and the financial service sector. The latter was a big export earner before the Global Financial Crisis, but not any more. Oil exports are also down, as there’s not much left of it under the North Sea. The tin mining industry’s dead – it was heading for a revival thanks to rising demand from China’s electronic goods factories, but the GFC stopped that.

The balance of trade has tipped against Britain, and under these circumstances it’s not surprising that the pound has fallen. But falling further won’t help the manufacturing industry much, and could hinder it with inflation feedback problems.

Yet I’m not “trying to argue that there is no scope for real output increases or rising employment in Britain as of this day”. I’m trying to argue that your own plan isn’t the best way to achieve it. Spending more while ignoring the other problems won’t solve anything!

The first thing Britain needs to do is get rid of Gordon Brown. Despite your unfunny jokes he’s a bigger impediment to progress than spending cuts are. We need someone in charge who understands economic efficiency.

The second thing Britain needs to do is simultaneously

• make whatever cuts it can to improve efficiency

• HUGELY increase spending on things that pay for themselves, while ensuring the money is always spent in the most efficient way possible.

To stop this huge increase in spending from dragging the pound down further, they should be part funded with ten year (or similar length) bonds in Euros and American Dollars.

Infrastructure funding should be brought forward as much as possible. After the economy recovers, it should be slashed, though this should be done in such a way that efficient use could still be made of the expensive machinery already purchased.

Britain will have to run surpluses for many years afterwards to pay for all this, but it’s still the best option.