I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

A mining boom will not reduce the need for public deficits

Australia is becoming caught up again by the rhetoric flowing from the minerals lobby that we are about to enter the “mother of all mining booms”. Almost every day now, the politicians, business spokespersons and the media are beating up this story. The minerals lobby has achieved spectucular success over the years in inflating its importance such that people genuinely believe our prosperity comes from this sector. Somehow we believe that this sector is our vehicle to Shangri La. Corresponding to all this hype is a growing push for significant cuts in public spending to “make room” for the mining boom. The debate is interesting because, like the intergenerational (ageing population) debate, it demonstrates how erroneous understandings about the monetary system and the role of the government within it lead to spurious conclusions. And all the while – labour underutilisation rates remain high.

Of-course, the concept that Australia’s fortunes are driven by the mining sector is a gross exaggeration. It is clear that the mining sector adds to GDP (about 6.7 per cent) but most of the talk about the “mother of all mining booms” are just the words of the spin doctors being well fed by the minerals lobby, which is very powerful in Australia. Australia has steadily increased per capita incomes over a long period of time and this growth is largely disconnected from the mining booms.

An associated debate relates to what are we going to do with the largesse that is coming via mining as the Chinese economy goes into double-digit GDP growth. I note that the largest contributor to GDP growth in China is currently (by a “country mile”) the public stimulus.

The previous conservative Australian government (1996-2007) is alleged to have squandered the previous boom (from 2004 until the onset of the crisis) on tax cuts which fuelled consumption. As if consumption is bad. I am not pushing a consumer-obsessed society but being able to consume goods and services is certainly better than not being able to do so.

The problem with the previous government is that it manipulated fiscal policy in such a way that the high income earners gained the most from the policy changes while low-income earners and public infrastructure investment were largely ignored. But this policy position and any policy position have nothing to do with any notion of “largesse” in the form of higher tax revenue. I will come back to that point.

In February 2010, the RBA Deputy Governor (Ric Battellino) gave a speech – Mining Booms and the Australian Economy – to the Sydney Institute (a right-wing lobby group), where he outlined the history of mining booms in Australia starting with the 1860s gold rushes.

He made the point that it seems “clear from history is that every mining boom was accompanied by increased inflationary pressure … [except he notes that] … in the 1890s boom, which began when the economy had large-scale spare capacity, was the rise in inflation contained to single digits”.

So if you have spare labour capacity then inflationary pressures are not inevitable. The reality is that any boom in nominal demand poses an inflation risk.

He also noted that the “role of the exchange rate in these booms” was important and that in:

… all the previous booms, however, the nominal exchange rate was either fixed or managed very tightly. The real exchange rate could therefore only adjust through inflation. In the current episode, with a floating rate, the behaviour of the nominal exchange rate has been very different from the past. It has risen early in the boom and by a large amount. This has been an important factor helping to dissipate inflationary pressures.

This cannot be understated. While many progressives want to return to fixed-exchange rates, a desire which reflects their mistaken view that they stabilise global financial flows, MMT considers a flexible-exchange rate regime to be a central pillar of currency sovereignty. By allowing the parity to adjust to external fluctations in demand and supply of the home currency in foreign exchange markets, domestic policy is freed to concentrate on advancing public purpose.

Fiscal policy, in particular is liberated by the floating exchange-rate regime. This point should always be considered when discussing fluctuations in demand for our minerals.

However, I am not arguing that a major event in a sector does not present a challenge to policy makers. In that sense, I partially agree with Battellino when he says:

History tells us that mining booms are periods of significant economic change and that they can pose complex challenges for policy makers. Key among these is the need to ensure flexibility in the economy and maintain disciplined macroeconomic policies in order to contain the inflationary forces generated by the boom.

Yes, the flexibility comes from floating the exchange rate. But in terms of macroeconomic policies, they should always be focused on advancing the domestic economy to full employment and then managing nominal demand growth to maintain that level of activity yet keeping a lid on any inflationary pressures. The fact is that successive governments have interpreted the “disciplined macroeconomic policies” argument to mean running surpluses, even when labour underutilisation rates were persistently high.

It is also sobering to examine the data from an historical perspective to see whether current rhetoric about booming economies etc is really warranted. Almost all the deficit hysteria can be shown to be false when you step back and take a long-term view of what has happened in the past. Unfortunately public commentary is focused on the immediate and very few journalists actually pause and wonder “is this period really exceptional”.

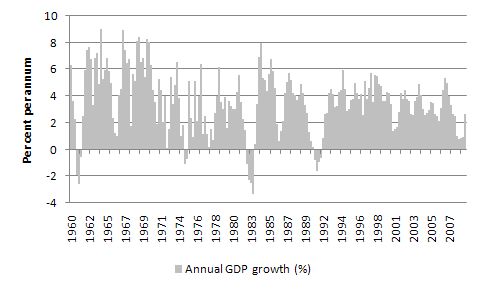

The current “mining boom” began in Australia around 2005 and apart from a lacuna in 2008-09, while the rest of the world melted down, there are signs of growth re-emerging in that sector. The following graph shows annual real GDP growth rates for Australia from September 1960 to December 2009. Data is available from the ABS National Accounts.

The big mining booms in Australia during the period shown were in the late 1960s/early 1970s; late 1979s/early 1980s and from late 2004 onwards. The obvious conclusion is that the current boom has led to above average growth for some quarters (the average for the period is 3.6 per cent per annum) but not consistently so. Indeed between 2004 and the onset of the financial crisis, real GDP in Australia averaged 3.5 per cent – that is, below average for the entire period shown.

Further, even at the height of the so-called boom (just before the crash) Australia still had around 9 per cent of its available labour resources underutilised – either unemployed or underemployed.

Much of the small inflationary spike in this period (some quarters just above 3 per cent) came from the imported oil price rises and the impact of an extended drought on food prices. In other words, they were of a supply-side origin rather than being driven by out-of-control nominal demand growth.

So it is hard to say that the most recent experience tells us that the economy is running too hot.

Today (April 16, 2010), Sydney Morning Herald economics commentator Jessica Irvine decided to address the issue of what are we going to do about this “boom”. She doesn’t question the rhetoric but uses it to give us a lecture on how we should manage government budgets in the process. She misses the mark – widely!

In the article – Ignoring future no way to spend boom – she reveals she doesn’t really understand how budgets operate in a fiat currency system. Given her mainstream characterisation of these matters it is no wonder she perpetuates myths that undermine the capacity of the public sector to deliver first-class infrastructure and full employment.

Irvine notes that Australia is:

… a mining nation. We dig up stuff and ship it out. Alongside professional services and some manufacturing, this is how we create real wealth.

Yes, we do have generous natural endownments of minerals that the rest of the world seems to want in fluctuating volumes over time. But mining accounted for only 6.7 per cent of real GDP in December 2009. Manufacturing was 8.6 per cent of GDP in December 2009 (and falling); Construction was 7.1 per cent of GDP and Professional, scientific and technical services accounted for 5.9 per cent of GDP.

Financial and insurance services are the largest sector in terms of contribution to GDP (9.9 per cent) at around 11 per cent is higher. At 5.0 per cent, public adminstration is not far below mining and if you include the other industries where the public sector dominates (education 4.1 per cent; health care and social assistance 5.7 per cent then the public sector would clearly outstrip mining in its importance to the local economy.

Anyway, these are facts and so are not worth disputing.

The point is that Irvine is pushing the mining boom line and the implications this has for public spending. She says:

Because the mining boom is hidden in remote areas of the country, it would be easy to overlook the dramatic impact it has on our lives. Or worse, we could take it for granted.

She then quotes a former bank economist now working in a research institute who makes the extraordinary claim that:

Australia’s public finances now more closely resemble those of a developing economy than those of an advanced economy, and that’s intended as a compliment.

So the links are being made between an alleged dramatic mining boom and our public finances. However, a moment’s reflection reveals that there is no link at all in the meaning that is being intended by the journalist and the commentator she chooses to quote.

MMT allows us to understand that Australia’s public finances (by which we mean the national government’s fiscal affairs and capacities) are exactly the same as any sovereign government which operates a fiat currency system with a floating exchange rate. They have nothing to do with industrial structure. This is a total myth and reveals a basis misundertanding which is sourced in the notion that such a government has to raise revenue before it can spend.

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows:

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending capacity is independent of taxation revenue. The non-government sector cannot pay taxes until the government has spent.

- Government spending capacity is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about “crowding out”.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

Please read my blog – A modern monetary theory lullaby – for more discussion on this point.

These principles apply to all sovereign, currency-issuing governments irrespective of industry structure. Industry structure is important for some things (crucially so) but not in delineating “public finance regimes” as you might believe if you had read the Irvine article and not understood these underlying monetary principles.

Their mistake lies in thinking that such a government is revenue-constrained and that a booming mining sector delivers more revenue and thus gives the government more spending capacity. Nothing could be further from the truth irrespective of the rhetoric that politicians use to relate their fiscal decisions to us and/or the institutional arrangements that they have put in place which make it look as if they are raising money to re-spend it! These things are veils to disguise the true capacity of a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

Irvine doesn’t get that at all. It gets worse.

She continued:

We’re about to get another opportunity to find out. For all the doom and gloom of the past two years, Australia’s economy is back to big-boom time. National income is again being fuelled by China’s voracious demand for our exports of iron ore and coal. Measures of consumer and business confidence are sky high.

What keeps Reserve Bank officials awake at night is not the risk of another world bust, but a home-grown explosion of over-exuberance. Should consumers rekindle their big-spending ways and abandon saving, the Reserve will be standing by to squash any inflationary pressure. This boom could end before it really begins. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We need a circuit breaker: lower government spending than might otherwise be the case.

At that point, we might usefully finish the blog and conclude that Mankiw is with us and go home.

Lets just assume for a moment that the scenario is accurate – the boom drives nominal growth to the point that all labour resources and capital are being deployed fully. So full employment and zero underemployment. We are so far from this point at present that I don’t see the scenario playing out anytime soon. But to see the argument we will assume it has occurred.

So inflationary pressures are building. Remember, the existence of price pressures in specific asset classes (for example, a real estate boom) does not constitute inflation. Inflation is the continuous upward movement in all prices (not a movement in relative prices).

Under the current policy regime, it is true that in these circumstances, the RBA will continue to hike interest rates until the economy is scorched – as it did in the late 1980s. Within this neo-liberal policy regime, that is all the RBA knows how to do these days.

But lets examine the fiscal policy options. Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

Why is lower government spending the “circuit breaker”? Upon what basis is that assertion made? Nothing is provided by the journalist so we can assume she is just apeing the anti-government policy rhetoric that went quiet when all the corporates were thinking they might need government assistance during the crisis but is now returning with vengeance.

The point is that fiscal policy is very well placed to deal with inflationary pressures arising from nominal demand growth outstripping supply growth. It can manipulate the tax structure and/or government spending to stifle demand to bring it back into line with supply growth. In fact, its direct and more immediate nature and its capacity to target any planned demand crunch makes it a much better counter-stabilisation policy tool than monetary policy.

The current crisis has demonstrated unequivocally the superiority of fiscal policy in manipulating aggregate demand. Think about the billions that have been pumped into bank reserves by central banks with very little impact on aggregate demand being the outcome.

So why would we want to cut government spending rather than lift taxes to choke off aggregate demand growth?

Why would we want to reduce the government net spending position (which is being implied)?

Well before you make any conclusions you have to consider the impact of these decisions on other sectors. If there is a very strong net export contribution to real output growth, then it is possible that the government can run surpluses and not undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to save.

The mining boom if it happens will not create an external surplus on the current account. Norway’s oil resources are driving a strong external surplus. But the mining sector is not large enough in Australia to do that.

So if our external position remains in deficit, which it surely will (especially as growth will stimulate imports) – then we know from our national accounting that if the government moves into surplus by dint of the growth in revenue from the boom and discretionary cuts in its spending, then the private domestic sector will be in deficit – spending more than it earns.

That is exactly what we need to avoid because household balance sheets are still fragile from the debt-binge of the last decade. In other words, if the external sector remains in deficit, the only way the private domestic sector will achieve a surplus position, is if the government sector continues to run deficits.

Further, by choking off private spending via tax rises the government can reduce the pressure on imports which will give more scope for exchange rate to provide an inflation-dampening impact. At the same time, the government can continue to deploy real resources not being absorbed by the mining boom via its own spending choices.

Irvine then goes one step further into the mire:

The Rudd government has committed to cap its annual spending growth to 2 per cent plus inflation. But with real spending tipped to shrink 1.3 per cent this financial year, that still leaves considerable wriggle room. And the temptations of government are great, excruciatingly so in election years. Rudd’s temptation this time may not be for tax cuts, but grand spending on “nation building” projects that will expand the economy’s supply potential in the long term, but put extra pressure on scarce supplies of workers and resources in the short term.

Well the government should dictate that publicly-funded projects have to employ those who are currently unemployed or underemployed and ensure the contractor provides the same with adequate training to accomplish the tasks required.

I remind you all that currently we have 12.8 per cent of our willing and available labour resources underutilised. That is a massive excess supply of labour resources. When you analyse many of the jobs that the corporates are claiming are in skill-deficits you realise that the skills required could be acquired in relatively short time spans.

So the national government should continue with its ambitious “nation building” which includes the provision of a national broadband capacity to take us into the current century, so neglected has investment been in this area. Further, the previous conservative government ran surpluses for 10 out of 11 years, in part, by starving investment in public infrastructure. The quality of our hospitals, schools, bridges, roads, etc all suffered badly. There is a massive catch-up effort still required to restore quality to these areas of our society.

Irvine then continued the standard neo-liberal line:

Given the limp-wristed hold politicians so often have on the public purse, calls are mounting for an automatic shock absorber to soak up revenue from higher commodity prices … [there is] … a growing chorus of economists calling for a “sovereign wealth fund”, a separate vehicle in which to park future windfall budget surpluses, when they return.

She then gives “credit of the Howard government” (the previous conservative government) because “as the mining boom reached its peak in 2006 and 2007, it began squirelling away some of the proceeds in a future fund to cover unfunded public service pensions and in two separate endowment-style funds, for health and for universities”.

The discussion is disappointing to say the least. Please read my blog – The Futures Fund scandal – for more discussion on this point.

In the midst of the nonsensical intergenerational debate that the previous federal regime used as a political tool to justify running unjustifiable budget surpluses the notion arose that the country would not be able to honour its liabilities to public sector superannuants unless drastic action was taken. Hence the hype and spin moved into overdrive to tell us how the establishment of a sovereign fund – ironically named the Future Fund (ironic because it actually undermines our future – more later) – would save the day.

The Future Fund is a sovereign fund which have become favourites of the neo-liberals over the last 20 years. The mythology that surrounded the creation of the Future Fund was aided and abetted by statements from the so-called markets. For example, the CEO of the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia claimed at the time that “the Future Fund was a savings vehicle while superannuation funds were investment vehicles with strategies aimed more at growth”. Nonsense!

The financial market players lapped it up because they knew they were in for more largesse at the expense of public spending. Corporate welfare is always attractive to the top end of town while they draft reports and lobby governments to get rid of the Welfare state, by which they mean the pitiful amounts we provide to sustain at minimal levels the most disadvantaged among us.

Anyway, the previous Federal government created the Future Fund in 2006 claiming that it would create the fiscal room to fund the so-called liabilities. Clearly this is nonsense. The Commonwealth’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained. So it would always be able to fund the superannuation liabilities when they arose without compromising its other spending ambitions.

The fund basically takes speculative positions on financial assets. So our Federal government continues on with its gambling ways in the World’s bourses while millions of Australians do not have enough work. It is a scandal!

Not only that – the fund lost billions. This is equivalent to the Government putting those billions into a bucket and setting the pile alight. Further, the managers have been paid millions to do it!

Now, while this in itself doesn’t stop the Government from spending any amount that they want – given they have no financial constraint – it does pose a political issue.

What if I said that the spending they put into the Future Fund was sufficient to employ all of the current unemployed and underemployed for about the next decade at minimum wages? They would immediately say, among other disparaging remarks, that there was no fiscal room to do any more than they are doing. Yet they are spending to buy financial assets instead which are going backwards in value.

So we have a situation where our elected national government prefers to buy financial assets which then lose significant value instead of buying all the labour that is left idle by the private market. They prefer to hold bits of paper that has lost value than putting all this labour to work to develop communities and restore our natural environment.

How could we have ever become entrapped by this level of absurdity?

An understanding of modern monetary theory will tell you that all the hoopla over the Future Fund (or any sovereign fund) is basically totally unnecessary. Whether the fund gained or lost makes no fundamental difference to the underlying capacity of the Federal government to fund all of its future superannuation liabilities.

The Commonwealth’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the purchase of a superannuation fund (in this case the Future Fund) in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system. That is, it represents lunacy!

The misconception that “public saving” is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media.

Irvine falls prey to this misconception. She says:

A common argument against such a fund is that it helps future generations at the expense of today’s. But the proceeds from a mining boom are different. This generation has no greater claim to ownership of Australia’s commodity resources than the next. Is it fair we should grow rich exploiting a finite resource? Furthermore, if we fail to boost national savings to offset the impact of the boom, it will be this generation of mortgage holders and business borrowers that pays the price with punitively high interest rates.

The Rudd government can learn from the mistakes of the Howard government, which largely spent the proceeds of the boom. Establishing a sovereign wealth fund would be a better way. And we’d be at less risk of blowing the economic radiator if we did.

First, the Howard government didn’t spend the proceeds of anything. It spent without the need for revenue because it was a sovereign government as is the current Australian government.

Second, running budget surpluses do not create national savings. There is no meaning that can be applied to a sovereign government “saving its own currency”. It is one of those whacko mainstream macroeconomics ideas that appear to be intuitive but have no application to a fiat currency system.

In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that Government spends by crediting an account at an RBA member bank. There is no revenue constraint. Government cheques don’t bounce! Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account at an RBA member bank. The funds debited are “accounted for” but don’t actually “go anywhere” and “accumulate”.

The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency.

So at the heart of all this nonsense is the false analogy neo-liberals draw between private household budgets and the government budget. Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts). Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained.

However, trying to squeeze the economy to generate these mythical “pools of funds” which are then allocated to the Future Fund as if they exist is very damaging. You can think of this in two stages. First, the Federal Government spends less than it taxes and this leads to ever decreasing levels of net private savings. The private deficits are manifest in the public surpluses and increasingly leverage the private sector. The deteriorating private debt to income ratios which result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity. Second, while that process is going on, the Federal Government is actually spending an equivalent amount that it is draining from the private sector (through tax revenues) in the financial and broader asset markets (domestic and abroad) buying up speculative assets including shares and real estate.

That is what the Future Fund is about. It amounts to the Treasury competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital.

However, as you can see from pulling it apart, this behaviour has been grossly misrepresented as providing “future savings” to pay for the superannuation liabilities. Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even.

In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments.

How can the government justify purchasing speculative financial assets which it has lost several billion on while holding when there were more than 9 per cent of willing labour resources either not employed at all or being forced to work less hours than they desired because of overall spending constraints in the economy?

If we want to provide for a better future the Government should be spending sufficient amounts to make sure everyone has a job. That is a minimum requirement for improving the future prospects. Then it might spend some of the $60 billion it put in the speculative Futures Fund on medical research to find cures for cancer and HIV and to make our public schooling system the best that money can buy. That would be a funding the future. The Future Fund does nothing for our futures and should be unwound as soon as possible and the executives made to earn a living somewhere else!

This debate then gets tied up in the nonsensical literature about the “optimal size of government” and I will write about that another day.

Conclusion

If the current mining boom does push the external position into surplus, then the national government can run surpluses without compromising GDP and employment growth and the need for the private domestic sector to run surpluses (and develerage).

However, our external position is unlikely to move into surplus, which means that public deficits will be required to “fund” the private domestic surpluses.

Commentators who do not recognise these intrinsic relationships that are embedded within our national accounting structure are prone to make erroneous conclusions and in doing so just become passive mouthpieces for the neo-liberal agenda.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

Maybe the public debt should be renamed as … the “Future Fund”! It constitutes the private savings of the country, due to be used to support future consumption out of whatever the real economy produces at that time. A little MMT jujitsu.

“If the current mining boom does push the external position into surplus, then the national government can run surpluses without compromising GDP and employment growth and the need for the private domestic sector to run surpluses (and develerage).”

Why would the spoiled and rich want the lower and middle class to be able to run surpluses (and delever)? They like their debt slaves just the way they are.

Bill wrote; Further, even at the height of the so-called boom (just before the crash) Australia still had around 9 per cent of its available labour resources underutilised – either unemployed or underemployed.

I was looking for commercial property management staff during this time and I was also trying realy hard to keep good staff that we had. Staff cottoned on to the power they had and wages went up higher than we could recoup in increased fees.

Because of this experience I am confused by the argument that we have cronic underutilization of workers. Is the underutized labour so unskilled that they are unemployable?

On Mining and GDP. Mining may not be a big slice of GDP but it does compete strongly for construction type laborers, electricians and mechanics. The small city business cant compete with the Miners who pay huge wages compared to what these jobs pay in the city. This then caused problems in 2005 to 2008 for the city in retaining enough workers to fill normal orders. This squeeze resulted in wages increases above CPI. This wages breakout, in my opinion, is the only real inflationary demon that matters. Out of range increases in wages starts, no matter what causes it, the whole price rise cycle that the RBA will stop by increasing interest rates to seriously stupid levels. Australia’s RBA is very proactive in this area so we can expect early increases in interest rates to head off what the RBA says it is charged to do, prevent inflation getting out of control.

My brother works in the mines in central Queensland Australia driving a water truck. He gets paid twice the wage he could get in the city!

The Government needs to develope large regional cities closer to the mines. Currently there are few if any cities to live in close to the mines. The young mums and dads are not going to take there families to live in places with no city style service.

Ciao for now. Punchy

Punchy,

The number of people looking for work is greater than the number of positions vacant. The hours of work desired by the labour force is greater than the hours of work available.

Which part of that do you find confusing ?

Hi Alan,

I understand the math but I operate a business where the “rubber meets the road”. If the underutilization of the workforce was so great in 05 to 08 why was it so hard to get staff during this period? Staff were moving from one employer to the next getting increased wages over and above a reasonable level because of a lack of property staff in the market. Like all markets if one side has an advantage they can’t help but profit from it. It should be the Gov job to smooth out the market to avoid either side from getting too much leverage on the other party.

As for people working casual that want more work I agree this is a big problem especially in retail. There is something wrong with the system because it allows Employers to have more casuals than they need for the hours they get. Having a big pool of casual labour makes running a retail business a lot smother for the business owner but it does not give the huge number of casuals enough money each week to pay for living expenses. These casuals are not casuals at all as the business is using them on a permanent basis. Retailers use a big number of casuals to prevent these casuals from migrating to Permanent Part Time or Full Time possitions by manipulating the hours worked by each casual. These people live on the edge every week. The deregulation of the labour market has left a gap that business has exploited i.e. the permanent part time and casual worker. So my question was why did it get difficult to find good semi qualified workers when the labour market was underutilized in 05 to 08. Either the underutilization is BS or there is more information on this group that will explain it.

Anyone know the answer?

Punchy,

Your initial example of your experience with commercial property management between 05-08 and your concluding statement “that the underutilised are just not skilled enough” is the exact reason for implementing a Job Guarantee system. Our current system of controlling inflation through allowing a level of labour market slack also known as the non accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) means that those who find themselves unemployed involuntarily due to a mismatch of their skills with those desired by the private sector (using your example in 05 to 08 there being 9% underutilisation but at the same time as a commercial property employer there clearly being a lack of skills within the pool of unemployed for your business) can find themselves with no real avenues for retraining outside of the private sector taking a gamble and doing in house training with those semi skilled workers. A government run Job Guarantee system as opposed to a welfare system which institutionalizes the unemployed through the NAIRU management of inflation, would allow the unemployed options for retraining and also provide downward pressure on wages within the private sector (which was your other point) due to the those in Job Guarantee employment being a better “reserve army” (a more skilled pool of workers as an alternative option for employees) than the current pool of semi skilled unemployed on centrelink.

I hope that helps to explain why within an economy under the current NAIRU welfare system that you can have skill mismatches between the pool of the unemployed and the skills desired by the private sector creating involuntary structural unemployment and therefore high levels of labour underutilisation. While at the same time have upward pressure on skilled labours wages due to the employees having no viable alternative pool of skilled or semi skilled workers from which to hire from.

Punchy,

Your question is about the microeconomics of the market rather than the macroeconomics. The macroeconomics part can essntially be solved by having the government act as an employer of last resort but trying to solve the micro side is simply pissing into a hurricane.

You should have either trained people for the positions or offered a larger carrot to the bunnies that already had the skills for the job.

Corporate welfare is certainly not the answer.

Nick and Alan thank you for making the effort to reply, much appreciated.

Alan our business has the lowest turnover of staff in our industry in our part of the world due to nice juicy carrots and the fact we really care about our people. It was still a very difficult time (05 to 08) to be an employer in our industry. I have a friend in the truck business and he had problems keeping diesel mechanics during this time as the mines kept taking his staff as soon as their apprenticeships were finished.

Nick, I would love to train more people. One of our best Facilities Managers was a cleaner when he started with us. We have payed for his training and this has really paid off for both of us (because he is still with us). We could do more training of similar people if we had a guarantee that as soon as we have trained them they don’t leave to work for the opposition. I know the Gov has tried all sorts of training assistance schemes and we have used a few, but the problem with training in the small business area is retention. As soon as they are trained they have a lot of new options for employment. Those benefiting from the training then are the opposition firm (if they leave) and the employee. The training firm gets none of the benefit of the effort it went to in training the employee if the employee leaves. We could spend a lot on training if a worker had to stay for a fixed period in return for the training. They do this in the army so why not in small business.

Thank you for the explanation of NAIRU. This is another example of the Government abandoning its people.

The Government has abandoned its people in the areas of retirement funding (do it yourself), employment (no one who wants to work and better his lot should be out of work) and Housing (this is shelter and everyone has a right to own their own shelter).

Starting to Rave a bit so thanks again for your replies. Cheers Punchy

Punchy,

Basic human capital theory assumes two types of training.

1. Is specialised training whereby a person’s learned skill set is not transferable to other companies; and

2. Transferable training whereby the skills taught in one work place can be used elsewhere.

Given that your workers fall into the second category I can well understand your frustration.

I think your suggestion about tying a worker to a fixed contract (similar to what the armed forces do) as a method of retention is a good one.

The worker gets certainty of employment and you get to enjoy the fruits of your investment.

Another solution might be to recruit a different type of person? Rather than someone who is ambitious to excel to the top you might be better served to look for someone who is perhaps a little bit outside the box.

Different industries of course but I often see people who would die to be apprentices / tradespeople miss out to people who have little or any intention of staying on the tools for anymore than 5 or six years. We so often hear the employer’s frustration of how they cannot keep workers and yet few if any ever acknowledge they have perhaps hired the wrong type of person.

I hope you get a solution soon though as you appear to be a good honest employer that looks after their workers.

Cheers, Alan

Easy as punchy I think Alan is right that you are talking about microeconomic issues, where as this blog is mainly discussing the macroeconomic issues. Though I think what you mentioned should not be disregarded so quickly by any economist as it clearly provides valuable insight into the effects of an economic boom within one sector and how it impacts upon employment, training and wages in other sectors of the economy. This clearly restricted your firms willingness to train new staff given the ease at which staff can be poached by the boom sector which you could assume was due to the large differential in wages between the two sectors.

The question is whether this was a unique experience to your firm or whether it is something that occurred across the board?

A firms willingness to train new staff is critical within an economy such as ours because we now heavily rely upon private sector training to meet the skill requirements of the economy. If the private sector training does not work effectively we might end up with a skill shortage!!!!!!!! There has been has been a major reduction in the last 3 decades of Government run training programs due to the belief that the market can provide better training on the job. If your example is happening across the board this shows the short falls in our reliance on private sector training as firms may be becoming reluctant to train due to their belief that they do not get value for money from training new staff.

Very valuable insight punchy

Thanks again. Something to think about!

Cheers Punchy

Hi Bill.

Thank goodness you and your colleagues are keeping the light of ‘reality’ shining in economics.

If you have time I would appreciate one clarification re what you’ve written above as otherwise I think I have a pretty good grip on Modern Monetary Theory.

You say above: “If the current mining boom does push the external position into surplus, then the national government can run surpluses without compromising GDP and employment growth and the need for the private domestic sector to run surpluses…..”

Now after reading Mr Mosler’s ‘Deadly Innocent Fraud #5″ and realizing the truth about the Australian foreign trade deficit (foreign sellers simply get dollars deposited into an Australian bank account and Australian buyers get the actual goods and services), I assume this also means that an Australian foreign trade surplus essentially involves Australian companies, as a result of sales of goods and services overseas, getting foreign currency in foreign bank accounts that they then convert to Australian dollars by buying those Australian dollars, with the number of dollars they receive being more than they could get by selling to, say, a potential Australian buyer (if there were one).

So essentially instead of selling a trade-able item to an Australian buyer for, say, $10 dollars, it is sold instead to a foreigner for the receipt, after the money is changed into Australian dollars, of, say, $15 dollars. But as that $15 is part of the existing Australian money supply, and presumably just represents the movement of dollars within the Australian private sector just like the movement of any other dollars, how does that transaction change anything in relation to the size of a government surplus that may be needed to take demand away from the economy if inflation threatens, or the size of a government deficit that may be needed to add demand to the economy if we have unemployment?