It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

When a huge pack of lies is barely enough

Today I read another appalling beat-up from the researchers at Société Générale. The fabrications and poor analysis contained in the Report should instigate class actions from their subscribers for grossly misleading them in their investment decisions. But the real problem is that the financial journalists seem content to function as meagre mouthpieces for this hysteria – to use their columns to spread it widely without the slightest introspection or critical scrutiny. The result is that the public are continually confronted with outrageous propositions – which carry not even a skerrick of truth. They then form fallacious perspectives about public policy that ultimately undermine their own welfare. The lies are all presented as being “iron clad laws” and “inevitabilities” and “fundamental truths”. But as I learned as a youngster – lies are lies.

I have been feeling fairly inadequate lately. When you read the financial papers on-line (including the blogs) you observe some common elements. Most have a nice header with the picture of the correspondent looking informed and earnest. They often have a catchy little header with a sub-title of alluring depth and meaning. Billy Blog looks a little wan in this respect.

So the billy blog marketing team has been at work with a vast array of multimedia specialists burning the midnight oil to come up with something more in line with the norm. I have done photographic shoots and had team meetings with a plethora of plugged-in and turned-on consultants. Finally we have narrowed down the new image which should place me fairly central in the mainstream financial market commentary.

Here is the pre-release for comment. I thought the photo of me was pretty flattering as I always come up better front-on rather than being presented from one side or the other. I also though the concept that my team came up with was persuasive and will improve my credibility out there in the markets.

I decided to offer the pre-release of the new approach after reading the latest commentary from so-called uber bear Dylan Grice at the Société Générale Research arm called – If It Can Happen In Greece, It Can Happen Anywhere. The day after this was released (April 12) the financial journalists and bloggers thought all their xmases had come at once. This was deep stuff and they all couldn’t get enough of it.

The tenor of the Société Générale report and the press reaction that followed convinced me that my new logo and concept will be a winner and billy blog is heading for uber status.

Grice’s central claim is that while everyone has been focusing on the fiscal stress currently being endured by Greece they are missing the point that this crisis is the start of many more to come. His overall claim is that “(i)f it can happen in Greece, it can happen everywhere else too, because Greece just isn’t that different”. So anyone with an inkling of an understanding of how different monetary systems work and how they differ across the globe will immediately dismiss this claim as nonsense.

But the financial market commentators and journalists have all gone into a lather about it. Conclusion: they haven’t a clue about how different monetary systems work and how they differ across the globe. Sadly, they are as ignorant as Grice and so the myths perpetuate into the public domain and poor policy decisions are implemented. And … we all are worse off as a consequence.

This this reaction is representative:

But the bad news is that this isn’t just about a few peripheral eurozone countries, or some dodgy unemployment stats. There are plenty more global debt time bombs primed and ready to explode. The ultimate damage to the financial system could make 2008 look like a walk in the park. Don’t touch government bonds with a bargepole. Here’s why…

I should note this WWW page has influenced our design team!

So debt time-bombs are ready to explode and wise investors shouldn’t go near them. I wonder if this goon has studied the public debt auction data lately for various countries. The times-covered ratios show no signs of falling significantly which means plenty of people (so-called investors) are not taking his advice.

I guess this commentator considers all those who for two decades have invested in every increasing Japanese Government Bonds issues are unwise. When will Japan explode? The bomb must have a very long fuse.

Yesterday (April 19, 2010), regular UK Guardian economics journalist Larry Elliot wrote – The UK isn’t so different from Greece: a financial crisis could happen here too also bought into the lie. He analyses various scenarios that might apply for the UK after the election and poses the question: “Could Britain be the next Greece?”

I immediately knew he was short of a story when I read the headline. I assume he was bored and staring out the window of his office wondering what the hell will I lie about today. Then he saw Grice’s red and white report pop up on his computer screen and he exited Solitaire which he had been mindlessly playing all day and started devouring Grice’s lunacy. Magic stuff – the UK and the US are the next Greek tragedy – headlines loomed and Elliot would meet his deadline.

His take on the story is that:

Worryingly, though, the question swirling around the markets now that Athens has signalled that it needs financial help from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund is: who’s next? There are those who say that Greece is a special case. It failed to come clean about just how messed up its finances were. The official budget deficit failed to take into account off-balance-sheet liabilities. It now needs to flood the markets with bonds to fund a double-digit budget deficit …

The assumption is that the US is too big to fail because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, even though it faces ruinously expensive long-term health costs. The assumption is that Japan is too big to fail because a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 200% can always be financed by high levels of domestic savings. The assumption is that Britain is too big to fail because, well, just because those sort of things don’t happen here. But we’ve heard these assurances before.

And … when have any of the nations listed in the last paragraph defaulted on their public debt? Answer: never for financial reasons while they were running fiat currency systems. Those assurances have never been violated.

None of these arguments reflect the considered analysis of the journalists. They are content to just mouth the claims made in Grice’s Société Générale report with no criticism or insight. They just rehearse his spurious arguments. The problem is that the public is not capable of discerning sound analysis that is based on a thorough understanding of how monetary systems actually operate from ideological and self-aggrandising rubbish.

Anyway, Grice motivated his discussion in this way:

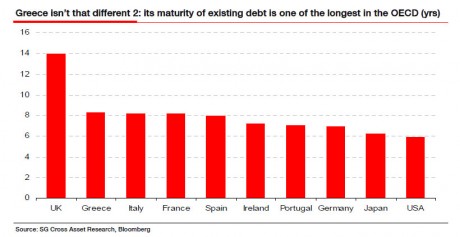

I’m not a bond strategist and I’ve not done anything sophisticated or clever, but by taking Bloomberg’s data for existing debt maturity for each government (red) and using the OECD’s projected 2010 deficits as a proxy for net new issuance (grey) my numbers shouldn’t be too far out. But if my numbers are even roughly right and issuance is the problem, Greece should have had almost the least to worry about!

Well I agree with him that he has definitely not done anything “sophisticated or clever”. In fact, his analysis is crude and dumb to say the least. This is the chart he is referring to.

So, on average, Greece and the UK have a far longer-dated stock of government debt than most other countries. So what is the point? The implication is that the countries with shorter-maturity exposures will be next in line for a funding crisis and become targets of the bond markets.

The Economics Editor of The Telegraph newspapers (Edmund Conway), another mindless mouthpiece, explained Grice’s graph in his article (April 14th, 2010) – Greek lesson: we are all in the same boat

What does this mean? Grice helpfully presents another chart which tells the story. Essentially, if you’re having to roll over lots of your debt each year, as you will when it expires so often (and because you don’t actually want to pay it back when it expires) it means you have to issue a hell of a lot more debt at the day’s going interest rate. Which in turn leaves you far more vulnerable to a sudden sharp increase in interest rates.

I should point out that Conway’s Telegraph page has also influenced my new blog concept that we are working on (noted above). The earnest look in his photo etc.

But he clearly needs some lessons in nautical matters. The countries shown in the graph are not “all in the same boat” because they span different monetary systems. This fundamental insight which I will explain in more detail below is lost on these characters.

Given Conway is the economics editor suggests to me that anyone should stop reading the Telegraph newspapers once you are done with the cartoons or the crossword. I was going to say the sport’s section but then you would be reading a lot of rubbish about soccer given it is a UK media outlet and I didn’t want to suggest you bore yourselves.

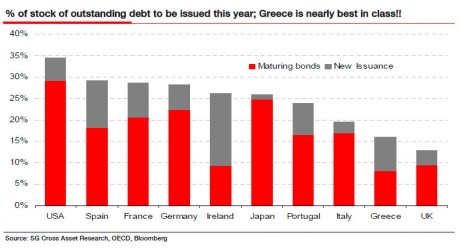

Anyway, here is that other graph that Grice produced. It attempts to break up the percent of public debt outstanding to be issued by the end of this year into new issuance and maturing debt. So Greece has a smaller proportion of maturing debt coming due this year than most other nations shown. So we have a comparison between the US, UK and Japan and a bevy of EMU nations.

Apparently this means something and the meaning is shared by all the nations in the chart given that Grice attempts to draw them into the same problem that Greece has faced.

The Moneyweek commentator, sourcing his quotes from other financial journalists, tries to explain it this way:

After the stimulus binge, it’s a debt hangover … Even if governments stop overspending now, they’ll have to compete more for cash with the private sector. So they’ll have to pay much higher rates on the bonds they’ll need to sell. This will drive up the cost of capital for everyone. That in turn will curb private sector investment. Without that investment, we won’t get the levels of economic growth required to generate the taxes that governments need to keep debt at manageable levels. Life will also get even harder for heavily-borrowed individuals. It’s a truly vicious circle.

So things look bad, even if governments stop overspending now. But the trouble is, they won’t stop over spending. Paul Farrell at Marketwatch has been digging deeper into America’s debt mountain. He spotlights a range of areas, such as homeland security, defence and local government, where spending is fast overshooting. The only way the US authorities will be able to plug the financial gaps will be to borrow even more money.

Its just all downhill!

First, the Greek government and all the EMU governments are at the behest of the bond markets in terms of the yields they have to pay to borrow. That is an intrinsic outcome of the way the EMU is organised. But it is all voluntary and the ECB could easily take the pressure of Greece and the other Eurozone nations if it wanted to.

How do these characters explain the fact that Japan now has the highest sovereign debt to GDP ratio and for nearly 20 years has had zero interest rates and very low long-term yields? The simple fact is that they cannot explain that because they do not understand how the monetary system functions and the implications of central bank liquidity management operations.

The crucial point is that sovereign nations such as Japan, the US, the UK etc can set whatever interest rates they choose at whatever maturities they choose. If these governments allow bond markets to set the longer-term yields then that is a political choice. There is no economic necessity for them to cede authority to the amorphous, amoral bond traders. Some might say immoral but we can leave it for now at amoral.

Sovereign governments have all the power and the bond markets have none. The only way the bond markets get a foot in the door is if the government opens it and invites them in. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

Second, the characterisation of the deficits as “overspending” raises the question – in relation to what? Given that unemployment and underemployment has risen sharply in all countries over the course of the downturn, the correct characterisation is that that goverments are guilty of underspending.

The important point that is clearly missed by these characters including Grice is that the budget deficit as a standalone outcome is meaningless. There is no information provided by currency estimates of net spending. You have to always assess the net spending in relation to the size of the spending gap, which is the difference between actual nominal aggregate demand and the demand required to support real output consistent with the full utilisation of productive resources including labour.

Unless you relate the public spending to that gap then you are no-where.

Third, government net spending does not compete “for cash with the private sector”. This is the financial crowding out myth that is found in all the mainstream macroeconmics textbooks. Governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

But at any point, the government provides the funds to the non-government sector that it borrows back. Please read my blog – Saturday Quiz – April 17, 2010 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on this point.

Fourth, the references to the intergenerational debate will be covered below.

Grice thinks he is onto something when he argues that Greece is adding interest servicing payments to the budget bottom line at a faster rate than they can cut the budget via the austerity package. He uses the standard mainstream government budget constraint analysis which suggests that if the public debt to GDP ratio is to stay constant the real growth rate has to be above the real interest rate:

If it does, the incremental government revenue generated by the economic growth will pay for the coupons on the debt. If it doesn’t, a shortfall develops between incremental revenues and incremental coupon payments and in the absence of further austerity, more debt is required to finance the deficit.

This might sound abstract, but it’s exactly what happened in Greece. When the first austerity plan was presented, Greece cut public sector wages by a painful 10% causing angry protest and social unrest, although it saved the government EUR650m. But the same austerity plan assumed Greece’s interest cost would be 4.7% and by late February it was paying 6.25%. According to the WSJ, this has blown a EUR700m hole in its budget, more than offsetting the savage public sector wage cuts already enacted.

This is not surprising at all. What would you expect would happen when there is a global recession that has hit the EMU region particularly hard and in the midst of that the Greek government then implements pro-cyclical fiscal policy in the form of an austerity package which further reduces economic growth?

That is why the Eurozone solution to their insolvency risk is so backward. They can only get out of their problem with economic growth, which requires strong aggregate demand. Fiscal austerity packages undermine aggregate demand. It was always going to be the case that the budget deficit would rise in Greece as a result of the austerity program. That is the nature of automatic stabilisers reacting against discretionary public spending cuts when there is no private demand growth capable of filling the spending gap.

Grice attempts to draw these nations together in this way:

… the most chilling similarity between the Greeks and everyone else isn’t in the charts above showing that their various debt metrics are in the same ballpark, it’s in the realisation that we too are subject to the same iron-clad laws of budget sustainability and that we too are as helplessly vulnerable to any reassessment of sovereign risk by the famously fickle Mr Market.

Please read my suite of blogs on sustainability – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3.

Grice hasn’t a clue what it means. There are no such iron clad laws. As pointed out above – Mr Market is powerless if the sovereign government chooses to use the opportunities that a fiat currency gives them.

The credit rating agencies might inform the markets that sovereign country A is a default risk but that will mean nothing unless the government itself allows itself to fall prey to the markets. The case in point is Japan – downgraded several times in the earlier parts of this century – with zero impact on its ability to issue public debt or the yields at which it issued it.

Further, sovereign governments can always decline to issue debt. While this might require some changes in regulations/laws etc, the fact is that their net spending capacity would be unaffected. The laws and institutions they have erected to force themselves to issue debt $-for-$ with net spending are all voluntary and have no economic meaning.

They are the realms of politics and ideology.

And, finally Grice gets to the ageing population myth – oh, how original!

But it’s not just about getting this year out of the way. If it can happen in Greece, it can happen everywhere else too, because Greece just isn’t that different …

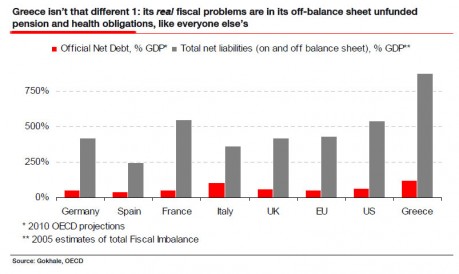

OK, so it misrepresented the size of its liabilities but so too do most other governments; its real fiscal problems are hidden off-balance sheet in the enormous welfare obligations it can’t afford to pay and so are most other governments; its debt maturity isn’t notably different from the rest of the OECD’s (at about eight years it’s actually longer than those of the US and of Japan); and its projected budget deficit is lower than those projected in the UK and the US …

Grice provides the following graph to somehow convince us that things are going to be bleak.

Note the terminology “real fiscal problems” that “it can’t afford to pay”. “Real” fiscal problems are not related to “financial parameter”. Further, sovereign governments (which issue their own currency and float it on foreign exchange markets) can always “afford to pay” for whatever real goods and services that are offered for sale. There is never a question that such a government can buy anything that is available for sale.

That is not the same thing as saying they should always buy everything that is available for sale at market prices. That is another question. But the point is that the idea a sovereign government can run out of money is nonsensical.

None of his inference is accurate at any level.

Governments in most advanced nations are facing a major medium- to longer-term challenge with respect the demographic change. A rising proportion of their populations will require retirement pension assistance of some kind and it is likely (but not inevitable) that health care outlays will also rise in line with the ageing population.

There is no doubt that dependency ratios are rising. In the blog – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time – I discuss the different ways of defining dependency ratios.

While dependency ratios will rise (however defined) if the population ages, governments have deliberately maintained persistently high pools of underutilised labour resources and have therefore heightened any challenges that will emerge from the rising dependency ratios.

So the only relevant question about the ageing population and the challenges for governments relates to whether the rising dependency ratio will reduce the growth of production of real goods and services in the future and therefore reduce material standards of living.

Grice is obsessed with the “financial” aspects of these projected changes and concludes that the implied increases in budget deficits will be unsustainable. His use of the term unsustainable is circular – true by definition and without any application to a modern monetary system where the sovereign government issues its own currency.

The mainstream emphasis on “costs” of retirement pension and health care systems and how these “costs” will “blow the budget deficits out” demonstrate how far of the mark they are in providing relevant commentary.

The “budget costs or outlays” are financial not real constructs. Once a person enters the intergenerational debate in this way – financial rather than real – you know they do not understand the true nature of the issue they are discussing.

The relevant issue relates to real resource availability in the future

There will be no financial constraints on any sovereign government running deficits in perpetuity should that be the appropriate macroeconomic policy setting (in relation to the behaviour driving the other sectoral balances). Ultimately, these deficits are endogenous which means they are driven by the non-government sector spending. If the latter wants to net save as an overall sector then the government sector has to run deficits for growth to be stable.

An ageing population will require choices to be made in relation to real resource trade-offs. Will there be enough real resources available? This is not a financial matter – it is a matter of whether there will be real goods and services produced in sufficient volumes for us and the government to buy in the future. If there are real goods and services produced in sufficient quantity to allow for adequate health care and pension entitlements (the former using resources, the latter commanding them) then the sovereign governments will always be able to afford to purchase them and provide them to our advantage.

How these real resources are distributed in the future becomes a political issue. The outcomes in the future will be resolved by political means in similar ways to now. But financial constraints will never be binding on a government with a political mandate to pursue high quality health care etc.

Clearly, if there are finite real resources then choices have to be made about what gets produced and provided. The question focuses on this issue.

If total spending in the economy including the rising pension and health care spending exceeds the real capacity of the economy to meet this demand with output then inflation becomes the issue.

To reduce the danger of this occurring in the face of rising dependency ratios, productivity growth is essential. This is why the neo-liberal approach to the problem which pressures governments to run budget surpluses now (erroneously characterising this as “saving for the future”) is so dangerous.

Resource availability in the future will be enhanced by the research and development that is done now. Mainstream remedies to perceived budget blow-outs typically manifest as cuts to education, for example. Nothing could be more stupid.

Further, maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. The emphasis in mainstream intergeneration debate that we have to lift labour force participation by older workers is sound but contrary to current government policies which reduces job opportunities for older male workers by refusing to deal with the rising unemployment.

Anything that has a positive impact on the dependency ratio is desirable and the best thing for that is ensuring that there is a job available for all those who desire to work.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

Conclusion

The vital point that is missed in all this hysterical analysis is that there is no valid comparison between an EMU economy and a sovereign economy. There is no solvency risk in the US, UK, Japan, Australia and elsewhere where the national government issues its own currency and floats its exchange rate.

The fact that the EMU has a totally different monetary system to these other nations mentioned in the Grice Report is seemingly lost on him and the troop of sycophantic journalists that think it is important to perpetuate his appalling analysis.

Greece and the EMU nations operate under a common monetary unit with one central banking system (the ECB and the national central banks). None of the individual countries can set its interest rate. The US, UK, Australia each have their own central bank which sets rates (for better or worse) according to the conditions prevailing in the respective countries.

They have no exchange rate flexibility and they have no fiscal redistribution mechanisms within the zone. They are financially constrained and have to tax or borrow to cover their spending.

Sovereign nations do not face these contraints. They issue their own currencies which float and can render the demands of the financial markets impotent should they choose to do so.

The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In and Counter-Conference Update

I mentioned that a group has formed in the US to promote MMT and the first event is a conference on fiscal sustainability on April 28, 2010 in Washington DC to rival the sham conference exploring the same topic which is being sponsored by the Peter Peterson organisation.

You can see Update with program etc.

The conference Home Page also information about purpose etc.

If you are near to Washington DC and have the means it would be great to meet you next week. As soon as a venue is confirmed I will post more details.

You will also note that I have included a fund raising widget on my right side-bar. Any help for the organisers will be very appreciated. Just click the image and open your bank accounts! The fund-raising home page is HERE

That is enough for today!

Bill,

I’ve been following your blog for a few months now and it’s been eye opening. Related to this article, I have two questions:

1) When people say “forgive 3rd world debt”, what do they mean? I’m assuming the debt of these nations are not in their currency and so they have trouble paying it back. Otherwise as you have mentioned many times, as the sovereign issuer of their own fiat currency, the debt shouldn’t be a problem

2) I never understood what happened during the Asian financial crisis in the late 90s. A lot of those nations, including mine, had to devalue their currencies or implement capital controls. Why was this the case? Looking through your archives I don’t think you have written about this topic specifically.

Once again, you are insulting football. Please stop that, seriously! I really like your style but it is not for everyone’s taste.

If you want to reach to a greater audience, you need to polish your style and remove unnecessary personal attacks. Please stop calling people dumb (most of them are not really dumb but has other motivations for the things they write) and stop commenting on their level of knowledge on economics. You can create the same effect and still be taken seriously (as you were complaining here that you are not listened enough) and be quoted in other places perhaps ten times more. Unfortunately for people like you, style does matter. I know you already know these. But, just in case…

Kemal,

Who are you defending? Foodball, economists and who else? i have some reservations of statements made in this blog regarding reality but you should not question the legitimate anger that most of us feel about the state of mainsrteam economics and the huge collateral damage is doing to so many people worldwide! I find the language in this blog highly civilized and probably needs to become more tough! Who is going to compensate the unemployed and those that suffer from criminal austerity measures? Get real!

Bill,

You say the govt is guilty of underspending. Shouldn’t spending be based on the needs of the public purpose, not on the needs of the economy? Taxes should be based on the needs of the economy. I agree the JG is needed for stabilization but should not be a permanant fix for a private sector that is overtaxed.

Also, how does MMT deal with the fact that energy is a limited resource (or at the least controlled by a monopoly-OPEC) well below full employment?

I live in CT (USA) and for the first time in my life (47 yrs) am looking forward to voting. Go WARREN!

Billy,

One of the things I like most about your blog is your willingness to take the gloves off and go after people. It’s refreshingly honest. Let ‘er rip!

“Also, how does MMT deal with the fact that energy is a limited resource (or at the least controlled by a monopoly-OPEC) well below full employment?”

How did we deal with it in 1974 and 1979? By switching from a petro-intensive economy to a more high tech one. That is actually a big part (at least as presented) of Japan’s biggest ever stimulus package, a year ago. MMT helps in this respect it says there is no need to forego the necessary investment to achieve this goal, as mainstream econ would have it, on the grounds that we can’t affort it : we can. I did not get the “below full employement part”, however.

PS : Here are recent questions for those who are knowledgeable about monetary policy. Thanks.

bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=9183&cpage=1#comment-5621

bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=9183&cpage=1#comment-5622

The ILO has just put out a study re deficit spending and job creation that promotes deficit spending for job creation indicating it will alleviate hardship and bring about fiscal balance more quickly. This fits into Bill’s with-friends-like-this-who-needs-enemies category. Still, it’s better than saying the unemployed should be left to twist in the wind and it does include a few interesting graphs.

http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/inst/download/promoting.pdf

With respect to Bill’s style, personally, I enjoy it very much although I can understand that some may not. I do wonder if an element of despair hasn’t crept into the blog which wasn’t there 6 months ago given how implementation of sensible policy seems unlikely in most countries.

Bill, I can’t decide if the photo of you for the newly entitled Lie Blog works or not. Your top top teeth are very pointy, a little scary and frankly, off-putting – no offence intended! Perhaps you should file them down a bit if you want to compete with the likes of Mankiw for influence!

markg,

I live by the LI sound but not in CT. There ought to be MMT group at meetup.com for the tri-state, no?

Re: “I find the language in this blog highly civilized”

Absolutely right. And also right about the epithet “criminal.” In a normal world, the banksters and their politician accomplices would be swinging in the wind–probably after having received a few dozen lashes. My vote would be for them to spend the rest of their lives making little rocks out of big rocks, or perhaps a very long day of cleaning houses for impoverished widows, and returning to the jail in the evenings, after a couple of hours of more work tending the gardens that supply their food. If they get too old or weak, put them outside as soon as the temperature gets well below zero. It’s what Eskimos used to do to help their people when they were too old and constituted a burden in difficult seasons.

My limited understanding of MMT leads me to believe that it is designed to facilitate management of the macro-economy, and my impression is that it does not (is not designed to) address microeconomic matters. For purposes of clarification could someone explain whether adoption of principles of MMT might facilitate recovery from the economic crises in the USA, in Greece; in the EMU; or in other locales. Is adoption of MMT even relevant to those crises? Could broad acceptance of the government’s role in money creation only occur as a consequence of a significant redesign/revolution in sovereign political control(s)?

You need to do some teach-ins in CA, we need it!

“or purposes of clarification could someone explain whether adoption of principles of MMT might facilitate recovery from the economic crises in the USA, in Greece; in the EMU; or in other locales. Is adoption of MMT even relevant to those crises? Could broad acceptance of the government’s role in money creation only occur as a consequence of a significant redesign/revolution in sovereign political control(s)?”

I think this could be answered like this : MMT says that government spending is not financially constrained if the gov has control over its monetary affairs. It should net-spend to make up for any shortfall in demand from the private sector as in the aftermath of a crisis to ensure full employment. Unfortunately these recommendations may not be followed as a result of misconceptions that are ingrained in dominant neo-classical belief system.

The members of the EMU, incl. Greece cannot issue currency. They must therefore borrow each Euro that they intend to net-spend from private entities, and are therefore financially constrained. They’re in deep(er) trouble, if you believe in MMT. Time will tell.

William Wilson,

In the presence of voluntary and involuntary constraints for a liberating paradigm to take hold, a crisis must occur to be able to weaken the forces (authorities) that mantain these constraints. Until of course, the contradictions of complexity that result from the reality of implementing the new paradigm imposes new constraints that lead to another crisis. Such contradictions of complexity include class struggle, the comflict between the public vs. the private orientation of reaction to surprises encountered in real situations and others. Of course, these issues are not handled by the MMT paradigm and will continue to exist regardless if the MMT policy is implemented in economies whose monetary system is based on fiat nonconertible currency with flexible exchange rates.

Dear Bill,

1.I have commented before and I will comment again. I do not see your economic argument that CB policy can and at all times control the long tails of the term structure of interest rates. I have even posted in comments in earlier blogs simple formulations of my theoretical work on interest rate determination that makes such clain ambiguous. Long tails are strange animals with asymptotic hyperbolic functions of long term unstable expectations and probability of default. There is no issue for short term rates.

2. I think that your fiscal policy position can be fortified if you distinguish in your analysis the difference between the endogenous and automatic income generation of deficit spending that does not deal with the structural ineficiencies of frictions, imperfections and inadequacies of resources and productive capacity that lead to inflationary pressures prior to full employment; and the horizontal voluntary(discretionary) fiscal policy of spending allocation that deals with these structural issues, eases inflationary pressures and liberates deficit spending to reach full employment with efficiency and higher income. If you think that you have such a distinction then it needs to be stated more clearly.

As long as we’e on pronouncements from the best and the brightest of Neoliberal-Land, the Financial Times has “America’s disastrous debt is Obama’s biggest test” by Roger Altman to add to the brew (19 Apr 2010). FT announces Altman as “chairman of Evercore Partners” and “deputy US Treasury secretary under President Clinton”. They fail however to mention his vice chairmanship at Pete Peterson’s Blackstone Group, a fact some might consider to be a more relevant disclosure considering the topic and timing of this opinion piece.

As near as I can tell, Altman is saying forget Afghanistan, unemployment, and healthcare funding (conbined?), if Obama doesn’t tackle the deficit/GDP problem real soon, interest rates for the dollar will go through the roof. New taxes and a $300B cut in spending (including “entitlements”) are just what the doctor (oops, he olny has an MBA … Chicago, of course) ordered, it seems. And of course, Mr. Obama must use ALL of his political capital to do this, so I don’t suppose that will leave ANY political capital left for anything else.

Oh, did I mention Altman had his fingers in BCCI and that he was on the guest list for Bilderburg last year?

Bill and ors,

Bill wrote:Will there be enough real resources available? This is not a financial matter – it is a matter of whether there will be real goods and services produced in sufficient volumes for us and the government to buy in the future.

What if the goods and services are available but only from a different Sovereign Country. Further what if the other Sovereign did not want to sell them in exchange for your countries money. Further assume you have an existing trade deficit with this other country. So the goods exist but you cant buy them.

If the product in question is rice and you need it to feed your people do you go to war to get it? Or should a country avoid the problem by abandoning globalization and become as self sufficient as it can? Anyone to answer as Bill is busy.

Hi Panayotis,

I’m interested in what you are suggesting in the first part of your most recent comment. By this I mean long tails of the term structure of interest rates?

“Long tails are strange animals with asymptotic hyperbolic functions of long term unstable expectations and probability of default.”

Is this an elaborate way of saying that what determines interest rates in the long run is uncertain due to the sheer magnitude of changing variables in the world that can and could affect long run interest rates.

Nick,

Yes and the fact that the long run is not an exponential smoothing function whose influence becomes trivial in effecting the determination of rates today. Things that can go wrong and big shocks such as black swans are less rare long term than we think. Furthermore, there is a segmentation effect (break) as the long run is not calculable (imperfect knowledge). A CB policy can use the issue of public debt as an anchor of risk free base rate, in the case of fiat nonconvertible currency system, but it cannot determine effectively the spreads at the long end for the reasons mentioned by you and me.

Panayotis,

Aren’t the long term rates reflecting expectations of future short term rates by a simple arbitrage (in expectation, not perfect) argument?

If the gov has control over the latter, it also has some control over the former. Sure, the market may want to price in some some probability of a black swan, that most likely, would translate into a relaxation in monetary policy, but I don’t see that it dramatically changes the analysis.

Two questions : a) is this what Bill is saying? b) If so, how do you disagree with it.

Bx12,

Long term rates are not reflecting expectations of future short term rates as main stream theory sais! To see how I disagree read my comments I have made several times before. Simply speaking, there are three aspects to non risk uncertainty, a) events subject to time that we attach no probabilities to them, b) possibilities that do not disappear and become irrelevant with time (power laws) so they cannot be smoothed away and c) punctuations of time that do not allow us to calculate their probabilities beyond (imperfect knowledge), leading to segmentation of long term rates from short term ones. These are different “animals” in Keynesian terminology that affect spreads seperately from monetary policy! I cannot speak for Bill but for myself and my framework of analysis!

Panayotis – liquidity preferences (-:

“Long term rates are not reflecting expectations of future short term rates as main stream theory sais! ”

that makes Warren Mosler a mainstream theorizer (his last post):

“Interest rates are primarily a function of expectations of future fed rate settings, along with a few technicals.”

Is it possible, instead, that you’re overemphasizing the “few technicals”? Let’s see

“Simply speaking, there are three aspects to non risk uncertainty, ”

I’ve never heard of non-risk uncertainty, I thought risk and uncertainty were closely related.

“a) events subject to time that we attach no probabilities to them”

This sentence does not make sense to me, which is different from “I don’t understand the concept”.

“b) possibilities that do not disappear and become irrelevant with time (power laws) so they cannot be smoothed away”

possibilities : you mean events? irrelevant, you mean what? I’m I supposed to infer both from “power laws”?

“c) punctuations of time that do not allow us to calculate their probabilities beyond (imperfect knowledge), leading to segmentation of long term rates from short term ones. ”

I know of punctuation in a written language so I take it it’s a metaphor you are trying to convey?

“These are different “animals” in Keynesian terminology that affect spreads seperately from monetary policy!”

Affect spreads, OK, but does it violate the fact, that LT = E[ ST ]?

“I cannot speak for Bill but for myself and my framework of analysis!”

Well, you got some ‘splaining’ to do, as they say in spanglish.

Panayotis – liquidity preferences is what I prefer!

Bx12,

You obviously do not understand what I am trying to say! By insulting my English is not going to win any argument. My positions are based on economic analysis and not on trying to attack anybody. You are trying to defend Bill but you repeat mainstream Economics! Have you heard of Knightian Uncertainty? Is it the same as risk and certainty equivalence? Have you heard of the hypothesis of Imperfect Knowledge? Have you heard of Equilibrium Punctuation hypothesis? Have you heard of the segmentation hypothesis? “animal spirits” of Keynes, Akerloff and Shiller is the expectations hypothesis of the term structure? Have you ever considered that danger includes terms such as risk, doubt, fear and ignorance (uncertainty of the known/unknown)? Are all these “a few technicals”? Have a nice day!

Ramanan,

Yes, but

long term rates is more than liquidity preference although in the presence of Knightian uncertainty you can only hedge it with liquidity holding in your portfolio.

Panayotis,

“You obviously do not understand what I am trying to say! ”

You obviously don’t know how to make yourself clear.

“By insulting my English is not going to win any argument. ”

I don’t see how it is an insult to point to what is not phrased correctly or not clear, if with a hint of derision. I’m actually granting you attention, which in hindsight, is more than you deserve.

“You are trying to defend Bill but you repeat mainstream Economics!”

Read me again : “Two questions : a) is this what Bill is saying? b) If so, how do you disagree with it.?”

Would I be defending Bill if I wasn’t sure where his stance is? I have hardly repeated anything, let alone mainstream economics.

” Have you heard of Knightian Uncertainty? Is it the same as risk and certainty equivalence? Have you heard of the hypothesis of Imperfect Knowledge? Have you heard of Equilibrium Punctuation hypothesis? Have you heard of the segmentation hypothesis? “animal spirits” of Keynes, Akerloff and Shiller is the expectations hypothesis of the term structure? Have you ever considered that danger includes terms such as risk, doubt, fear and ignorance (uncertainty of the known/unknown)? Are all these “a few technicals”? Have a nice day! ”

Some of them, but I don’t bring them up unless it serves a purpose, rather than wear them on my sleeve pompously, as you apparently do.

As the French would have it : “La culture, c’est comme la confiture, moins on en a, plus on l’etale” i.e. Culture is like peanut butter, the less of it, the more you have to spread it.

Bx12,

Your not interested to discuss Economics but to reveal your insecurities. I do not need to wear anything or prove anything. The insulting statements you make shows your education and culture. I have taught enough students and run enough organizations to know that you do not convince others by insulting them.

The hypotheses I brought up have a relevance and are incorporated in my theoretical work. You are right, you might not understand what I am saying because of the possible poverty of my short comment in this blog. I accept this responsibility although this does not require an error of my argument. I have mentioned my view and I even showed some simple formulations in previous comments. I repeat that you are presenting a mainstream view of the expectations hypothesis of the term structure of interest rates shared by many of my past teachers such as Milton Friedman, Robert Barro, Harry Johnson and many others of the monetarist and neoclassical schools. Is this the company you want? Cant you see the difference between expectations and sources of uncertainty, MEC, animal spirits and other long term instabilities? Have a nice day! By the way in my many summers studying in Paris I did not realize that the French like peanut butter. I learn all the time!

“Your not interested to discuss Economics but to reveal your insecurities.”

Sure, Dr. Freud. If I’m going to think by the same ground zero psychology as you do, then

“The insulting statements you make shows your education and culture. ”

shows that you are positioning yourself as the victim. Well, I’m sorry to say that you don’t inspire me much sympathy, so it doesn’t work with me.

“I have taught enough students and run enough organizations to know that you do not convince others by insulting them. ”

Well I knew that before teaching students and running any organization. It’s rather basic, actually.

“repeat that you are presenting a mainstream view of the expectations hypothesis of the term structure of interest rates shared by many of my past teachers such as Milton Friedman, Robert Barro, Harry Johnson and many others of the monetarist and neoclassical schools.”

Once again, showing off your pedigree (it at all credible) only to contrast it with how special you are. And I’m the one with insecurity?!

By the way, all the buzzword you are using such as Knightian uncertainty were amply disseminated by Nassim Taleb who has a gift for talking loud. Are you just trying to catch on to the bandwagon?

“Have a nice day!”

Thanks, but again?

“By the way in my many summers studying in Paris I did not realize that the French like peanut butter. I learn all the time!”

Is this the best pun you can come up with?

PS :

I sincerely hope you are only posing as an academic. You not only reinforce the stereotype of irrelevance and arrogance but I also have doubts about your actual academic abilities. Sorry, but your pitiful observation about peanut butter in France (ha ha ha) gave it away.

Bx12,

You continue to insult me and your comments show who you are! Why would I need your sympathy or your approval?

You know nothing about me and my background and I am not posing anything or misrepresent myself. I mentioned my past teachers to show you that I have studied mainstream economics from the source and I have come to reject it.Attacking me personally does not prove your argument. You have every right to have doubts about my academic credentials (although you are wrong!) and you have the opportunity to judge my views by reading my comments. Instead of trying to attack me personally, learn to carry on a dialogue. You still have not dealt with the points I raised and are written in my theoretical work and I do not hide them. So, Frank Knight and Keynes that worked on concepts of pure uncertainty are repeating Taleb?

As far as the french saying you mentioned, I thought you might have lived in France and wanted to tell you that none of my French friends ate peanut butter. If you are looking for a fight, this blog is the wrong place for it. Grow up!

Panayotis,

The point of saying it in its original language is that the ending of “culture” echos that of “confiture”. It’s called a rhythm, although it’s a pun, not a poem. Once you translate it, the rhythm is lost and there’s no need to translate word for word. So you might as well replace jam by peanut butter because it is more distinctively English-speaking-world (funny how eating habits overlap with the language) and therefore resonates better with English speaking people.

I’m waiting to have kids before going to Disneyland-Paris, but maybe I could ask you : how is it?

BX12,

I have never been in that Disneyland and I do not have kids. As far as the language is concerned I do speak French and I wanted to joke back because I never saw a French person eat peanut butter! I wanted to release the tension of the conversation! Maybe sometime when you have cooled down I can show you the difference between short term and long term rates and while monetary policy can control the first it has difficulties controlling the second. These “technicals” are more important! Have a nice day!

Panayotis

“Have a nice day!”

Again?!

I’m already cooled down as it is as the dog on my lap can testify, but sure, let’s talk it up another time.

Hi Panayotis,

Just to pick up on my question regard long tails and term structure of interest rates….Your explanation is very mathematical of what is a clearly a social phenomenom. Many economists including Keynes and Minsky regarded mathematical explanations as being inherently limited in explaining the social world in which human interact and make decisions. In the end these human interactions and decision making are the determinants of the long run. You can’t mathematically model the aggregates of all the individual human decisions made around the globe.

One area that I would be interested in from your theoretical work is the long run determinants of the Japanese interest rates? Japan have run continual budget deficits for decades yet still have really low interests rates. Advocates of MMT argue that Japan is operating with an understanding of MMT.

Dear Panayotis (at 9:36am)

Thanks again for your great input to the blog.

You said:

I have not said the central bank can control all rates at every maturity. What they can clearly control without question is the public debt yields at every maturity. This is not subject to any notions of uncertainty. Simply put – the central bank offers to buy whatever paper is available at whatever maturity at a fixed rate. If the private placement auction fails to issue at that yield then the central bank buys all the paper.

It is possible for some dislocation to occur between public and private debt along the curve under these circumstances, particularly if inflationary expectations drive a rising spread on long-term private paper.

best wishes

bill

Dear Punchy at 4.43pm

The questions you raise about are difficult for sure. A nation that has to import food and water is in strife and has to export to get the foreign exchange necessary to make the purchases.

It is situations like this that the IMF (or a similar body) has a real role to play to ensure that the local currency has purchasing power in foreign exchange markets. That is one of the essential financial reforms that is required.

A sovereign government can only buy what is available for sale in its own currency. Sometimes it will need help from outside to extend that capacity.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bx12 at 1.14am

I have just noted that my concerns have always been about the public debt yields along the curve. The central bank can clearly control them if they wish at all times and all maturities.

What drives differences between the private spreads is another matter and Post Keynesians tend to emphasise the concept of uncertainty (about everything) which I think Panayotis has been trying to explain (fairly well). There is a fundamental difference between risk and uncertainty. The latter has no definable probability density function because you cannot know all the events that would be included under the curve. In reality, people act with bounded rationality which means they abstract from the unknown and attempt to close the PDF anyway – by leaving all the possibles they cannot get their head around out!

So they sail by the seat of their pants and currently become unstuck!

best wishes

bill

Dear Ramanan at 2.35am

Liquidity preference is more about why you would hold cash or near cash rather than why you require a higher spread at longer maturities. The latter is about uncertainty.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bx12 at 4.09am and Panayotis

I appreciate both your contributions as I am sure all of the participants to the community here do.

But lets keep our dialogue here as friendly as possible without personal inferences. The aim is to test arguments with robust combative exchanges but to leave the person intact.

best wishes

bill

Panayotis, since there was a discussion about language usage and understanding of matters here are my 2 cents which I actually wanted to say for quite some time already but never did because was afraid to insult you. However communication is key in addressing miscommunication so here we go.

English is not my native language but I am not a beginner and can survive in business environment with my current level. However at some point of time I stopped reading your comments. Not because they are meaningless but because they are not digestable. I tried hard but often I simply fail to decipher single sentences not speaking about whole passages.

I remember pretty well one of my professors at the university. His favorite saying was that a concept that you can not explain to your gradma is a wrong concept. I hope it helps.

Dear Bill,

Thank you for your response. You are obviously talking about monetary systems where there is no constraint for the Central Bank to buy directly and monetize all available public debt at all maturities but in that case I do not see why it will do that and not have the treasury spend directly by crediting private accounts. The Treasury will issue public debt if it wants the private sector to have an instrument to save that is relatively less risky. However, at long maturities there is an uncertainty and other factors that come into play and this is displayed in the secondary markets that public debt trades. If such secondary markets exist the CB must continuously have to intervene and this makes control of long maturities with unstable spreads more difficult. As about my comments in your blog, I have tried to be civilized in my comments to others out of respect to you as a host and also for my own integrity.

Nick,

I agree about mathematical presentations and I use them only as a tool of communication in my work for those who want to use them. As far as Japan is concerned I did not say that because of budget deficits rates have to be high and rising. All I say is that at the long end of the structrure there are additional factors such as uncertainty that can lead to an unstable spread which is more difficult to control, especially for private debt.

Sergei,

I apologize if my communication is subpar. There have been others (teachers, students, professionals) who had difficulty with my presentation. My only excuse is I type much slower than I think and try to keep comments short for things that take a lot of analysis especially for people that might not be familiar with some technical issues. Unfortunately, when I comment in blogs I do not have the priviledge of secreterial help to correct my mistakes as in more formal presentations.

Panayotis,

I see your points and am very empathetic to your views. I guess you want to see some formalism where there is no “expectation of the central bank reaction function” used. You may be interested in this presentation by Marc Lavoie, particularly Slide 21.

If I understand you correctly, you are looking for a mechanism which can in some sense describe long term yields, perhaps in a dynamic and stock-flow consistent manner.

Btw, I am active in this blog but haven’t kept up with the comments section in this blog recently. Where have you provided the references to you work ? Don’t ask mine, I am not in academia, but highly interested in Post-Keynesian Economics.

I’m actually in synch with Panoyatis on this one ( I think )

“You are obviously talking about monetary systems where there is no constraint for the Central Bank to buy directly and monetize all available public debt at all maturities but in that case I do not see why it will do that and not have the treasury spend directly by crediting private accounts. ”

“Monetizing public debt” (a misnomer as per Bill) means buying bonds at issuance, right? This creates a supply of reserves (although this is less clear to me as when the CB buys treasury bonds from the secondary market) and should therefore bring the interbank rate down. This may or may not be compatible with maintaining a target rate : it cannot be discretionary. I actually raised a related concern here :

bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=9183&cpage=1#comment-5622

PS: I take note of Bill’s call for courtesy and will try to remind myself of it.

PS2: risk != uncertainty must be a convention that Post-Keynesians are privy to. I like good old Rumsfeld’s known unknowns vs unknown unknown depiction better.

Ramadan,

Thank you for your comment.

1. Regarding the reference on stock-flow consistency models of national accounts I have observed before on this blog that although correct at a moment of time they use static matrices and they are not dynamic with feedback loops. I have not read this reference yet and it might present a different story and I plan to read it.

2. The previous comments in this blog with some simple formulations, were April 1, 2010, Nos. 15 and 18, just before and after your comments that day!

3. I have been working recently on yield spreads with simple versions as above and some more complex/stochastic versions. After analysis I have come to focus on a) the calibration of the probability of default using a Poisson structure with a jump diffusion model whose jump term is power law formulation specified as an asymptotic hyperbolic function. B) the concept of pure uncertainty which I have modeled as a Bernoulli process variant with the number of occurences ( as time term) and a constant coefficient subject to surprise induced shocks. C) Liquidity preference that protects against this uncertainty. A regression here.

4. In order to understand uncertainty someone must realize that if behavior is the burdened response (adjustment) to an incomplete operation of occurence, a behavioral decision is exposed to danger and a behavioral praxis is subject to diseconomies of scarcity. Focusing on danger exposure I have come to decompose it in four sections. First, calculable estimated risk protected by insurance, doubt of estimated risk protected by flexibility (options) of response, fear of effects protected by sensitivity measures and ignorance( uncertainty or known/unknown) which is protected by liquidity as measure of precaution and prudence. All these have math representations. However, there is an additional point of liquidity preference, over and above uncertainty protection. There is the Keynesian issue of other motives. I see it as a general transactions motive subject to transaction costs and includes a term motivated by exchange substitution, a term motivated by market arbitrage and a term motivated by speculation. Obviously, these terms of transaction motive for liquidity are related with the short end of portfolios and yield structures and the uncertainty/precaution motive is related more with the long tail of these portfolios and structures. I hope this brief presentation satisfies your concerns.

Panayotis,

The default modeling using Poisson processes can be used for corporate debt but I am not sure how you can use it for government debt. Usually such default models are calibrated using spreads to the government yield curve.

More importantly, the concentration of the approach I linked is not much about probabilities of default, but about scenarios leading to trouble etc. For example, one can create a model with two countries with a common currency and one central bank – arrangement which exists in the Euro Zone, interacting with another country which has its own currency and a floating exchange rate and see how the various sectors interact with one another. The way of studying is a bit different: questions asked are – what happens if one country has a higher propensity to import than the other country with which it shares its currency, how will interest rates behave etc. Plus if this Euro Zone country faces problems with its debt goes into austerity what happens etc. Yes, according to this G&L analysis austerity may solve the problem of rising yields (in case there is no default), but will lead to lower output and employment.

Ramanan,

I think that we are talking about different things. However, notice that austerity measures in my approach, in opposition to mainstream theories, as they bring lower output and employment they end up raising long term rates. I use Poisson distributions becuse I assume many types of bonds, many countries and market participants with some independence from each other. Are they risk free from default or thought to be so? Look at Greek and other Mediterranean spreads to see my reservation! However, the fact the jump effects are more Pareto based, I introduce tail shock events that are less rare than otherwise assumed for the long term that in many cases they are modeled to exponentially decay with time. I am always open to constructive suggestions. I agree that for corporate debt this is more stronger.

One more point that I did not dealt in my previous comment but it certainly concerns me dealing with the long term. This is the so called “animal spirits”. Some think that they are equivalent to expectations. In my opinion it is not true and is another animal! It is internally based, an attitude, moods, a perspective, maybe insticts, best summarized my Aristotelean disposition. My approach is to think of them as an outcome of complexity that entangles adjustment and induces a motivation process or excessive behavior to exploit opportunities that emerge from this entanglement of the factors of adjustment. Speculation, overconsumption, aggression, etc. can manifestations of this disposition either positive or negative. As Keynes implied they are relevant for the long term and they affect the instability of long term spreads.

Another issue is whether is difficult for monetary policy to stabilize them. Notice that using Control theory, engineers will know this, the concept of “difficulty” is in relation to the stability of the relationship you are attempting to control. The more unstable the long end is the more difficult is to control it.

Panayotis,

Yes we are talking past each other! However, my comments were really to get you interested in some of the factors you may want to consider.

Ramanan,

Thank you for your comments and suggestions.