It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

The ECB plan will fail because it fails to address the problem

Last Thursday (September 6, 2012), the ECB released details of its new program the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) which will replace the Securities Markets Programme (SMP). The latter saw the ECB buying Eurozone government debt in the secondary markets. In the OMT Announcement – the ECB declared it would set “No ex ante quantitative limits are set on the size of Outright Monetary Transactions”. The ECB decision to purchase unlimited volumes of government debt means that any private bond trader that tries to take a counter-position against any Eurozone government will lose. It means that the central bank can set yields at wherever it wants including zero. It means that all the mainstream economists are wrong if they claim that deficits drive up interest rates to the point that governments become insolvent because the private bond markets will refuse to purchase their debt. But once you understand the significance of that you also soon realise that the ECB rescue plan will fail. Why? Because it doesn’t address the core problem – that southern Europe is in depression and the only way out is for budget deficits to expand. The ECB will buy unlimited government bonds – but only if they have succumbed to a fiscal austerity package that ensures their growth prospects deteriorate even further.

What is the ECB going to do?

The ECB will purchase short-maturity bonds (1 to 3 years) in the secondary market. Essentially, the primary bond dealer will know that they can easily off load any bond purchases in the secondary market to the ECB.

The ECB will massage their action – to make it look as though they are only undertaking the purchases to help the operations of the financial system rather than fund government deficits – by claiming that because the government debt markets are part of the overall financial market transactions their purchases will improve the monetary transmission mechanism which will, in their eyes, help support the private demand for credit.

The logic of the action is that by buying large volumes of short-term maturity bonds, the price rises and this drives down the yields. Bond traders then are forced to purchase longer maturity government bonds if they want higher yields which then drives prices up and yields down.

Lower interest rates then are considered conducive to rising private demand for credit which, in turn, will help stimulate private investment spending and kick-start growth.

Their statement has some other significant points.

First, they are only going to purchase government bonds if the nation is already undergoing a fiscal austerity program forced on it by the Troika. The ECB say:

A necessary condition for Outright Monetary Transactions is strict and effective conditionality attached to an appropriate European Financial Stability Facility/European Stability Mechanism (EFSF/ESM) programme … The involvement of the IMF shall also be sought for the design of the country-specific conditionality and the monitoring of such a programme.

By which you understand that the ECB decision is in denial of the real problem – a lack of growth. They are saying that they will keep a member state alive so that it can die slowly. They know that if such a nation is forced to deal with private bond markets to gain funds to cover their budget deficit – that the Eurozone will collapse.

The ECB also said that once the conditionality was satisfied that:

No ex ante quantitative limits are set on the size of Outright Monetary Transactions.

Which means it is a mega SMP scheme. While the whole implementation plan is flawed (being conditional on fiscal austerity) the announcement demonstrated categorically that currency issuing authorities have not financial constraints. They can purchase whatever is for sale in the currency they issue.

It also demonstrates that the currency issuer can always usurp any market machinations attempted by private bond traders. The conception that it is private bond markets that set yields and governments have to live in fear of these markets and maintain fiscal austerity is a lie.

Governments (currency-issuers) can run whatever deficits they choose without worrying about what the private bond markets think or do – should they choose to exercise their authority over those markets.

The current situation where governments issue debt into the private sector to match their deficits $-for-$ is just an elaborate pretence as well as being a very coordinated system of corporate welfare.

The ECB announcement clarifies all of those central Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) propositions, although they didn’t disclose it in that way.

Further, the ECB said:

.. that it accepts the same (pari passu) treatment as private or other creditors with respect to bonds issued by euro area countries and purchased by the Eurosystem through Outright Monetary Transactions, in accordance with the terms of such bonds.

Which is a change from the PSI scandal where it exerted priority creditor status.

They also provided a sop to the Germans who are hyperventilating over the announcement. The ECB said that:

The liquidity created through Outright Monetary Transactions will be fully sterilised.

Which is another one of those myths that the mainstream perpetuate to make themselves feel more comfortable.

The Securities Markets Program (SMP), which the OMT has replaced also “sterilised” the ECB purchases. You can also learn about the “sterilising” functions associated with the SMP from HERE (go to the Ad-hoc communications tab on the page).

The OMT will work in a similar manner.

For example on November 7, 2011, the ECB announced the following “fine-tuning operation” – a weekly event:

As announced by the Governing Council on 10 May 2010, the ECB conducts specific operations in order to re-absorb the liquidity injected through the Securities Markets Programme (SMP). In this regard, the ECB will carry out a quick tender on 8 November at 11.30 in order to collect one-week fixed-term deposits with settlement day on 9 November. A variable rate tender with a maximum bid rate of 1.25% will be applied and the ECB intends to absorb an amount of EUR 183 billion. The latter corresponds to the size of the SMP …

So the ECB buys the bond of some member state in the secondary market (that is, after they have been issued by the government in question in the primary tender market). The ECB just conducts an electronic transfer and bank reserves rise (see more on this below).

The ECB then offer deposits to the banks (in this case – with a ceiling of 1.25 per cent yield) up to the volume of outstanding bond purchases. So the banks swap reserves for an interest earning account with the ECB.

This swap is referred to as the sterilisation operation and allegedly “neutralizes” the bond purchases “by draining the same amount of money from the banking system”.

Mainstream economists say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

This is a common misunderstanding. What happens when a government spends and issues a bond to cover that spending (borrows back what it has spent)?

All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

The reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. As noted above, all components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk.

The following blogs might be of interest here – Why history matters and Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary and The complacent students sit and listen to some of that.

In this case, the so-called sterilisation is just an example of smoke and mirrors. The deposits that the banks make with the ECB do not reduce their capacity to lend on iota.

On the same day (September 6, 2012), Eurostat published the updated estimates for second-quarter GDP in the Eurozone – Second estimates for the second quarter of 2012 – which showed that reL GDP growth in the Eurozone decreased by 2 per cent compared to a zero growth figure in the first-quarter. Both household consumption and private investment growth were negative for the second consecutive quarter.

OECD boss Angel Gurria told the EC Conference that I attended last Thursday in Brussels that it was downgrading its estimates of Eurozone growth for 2012 further – from its already dire forecasts.

Southern Europe is in depression already with no end in sight.

There can be no sense in a solution that forced nations further into depression and ensures that other nations that are bordering on that state cross the line too. The OECD now estimates that Italy will contract by 2.4 per cent in 2012. Greece has lost 20 per cent of its GDP since the crisis began and the situation is getting worse by the day.

The irony is that Germany think Mario Draghi is proposing wild monetary prolifigacy whereas in fact he is part of the mainstream neo-liberal elite.

As this crisis drags on and morphs into increasingly bizarre outcomes, it is clear the one of the central culprits is the ECB itself. It alone has the currency-issuing capacity to provide sufficient demand to allow the region to grow again.

The crisis is about a lack of growth. The bond markets would not be attacking governments – one by one – if their economies were growing and unemployment was low and tax revenues were high.

The crisis is not about the particular policies of the member states. It is clear that there were “unsustainable structural policies” pursued by governments – deregulation of the financial sector, not enough regulative oversight of real estate markets (including allowing private citizens to fund mortgages in foreign currencies), a bias towards budget austerity (under the Stability and Growth Pact) which meant that growth had to rely largely on private credit expansion – etc.

This behaviour of governments leading up to the crisis was based on exactly the same logic that is driving the fiscal austerity – that free markets are best and government should have as small a footprint as possible.

The neo-liberal policy positions that governments adopted and the conservative design of the European Monetary Union were directly responsible for making the Eurozone highly vulnerable to perturbations in aggregate demand.

When the Eurozone experienced the large and rapid negative demand shock in late 2007 it was obvious that a rapid response from the currency-issuer was required to prevent the bond markets from raising the alarm bells as the automatic stabilisers (tax revenue collapse) drove the budget deficits up.

The fact that the ECB – as part of the destructive Troika – chose to inflict a negative growth strategy on the region – by forcing fiscal austerity onto the weakest economies guaranteed that the problem would morph into a full-blown crisis.

The fault lies squarely with the Weimar-obsessed ECB. The leading officials should resign en masse and hand over the “fiscal authority” to those who know how to make economies grow.

So while they have declared they will buy unlimited volumes of government debt – they will only do so if the member states are in depression. It is no rescue plan at all.

And then you read this Financial Times article (September 9, 2012) – Global economy: Not so different this time – which agonises for 2072 odd words about why growth is not more robust than it is but fails to actually consider the obvious, preferring instead to argue within the almost irrelevant confines set by the neo-liberals as a way to divert our attention from the obvious.

The article thinks there is a crisis in central banking because:

… the deeper central bankers delve to solve the developed economies’ woes, the more some in the profession fret.

The dominant paradigm has successfully diverted our attention from basic understandings such as spending equals income which generates employment and that government policy can directly influence spending – it is called fiscal policy.

So if non-government spending is insufficient to drive growth at levels that bring unemployment down, the obvious solution is that fiscal policy has to fill the gap.

It is so obvious and simple that the neo-liberals have had to erect a complex edifice theory and threat to undermine our acceptance of that truth. So we get a litany of lies such that governments have to borrow to fund the spending and that drives interest rates up, undermines the future of our children and their children, is inflationary, is wasteful, will create crippling tax burdens, will undermine private incentive, will lead to a loss of our freedom, will destroy our national prestige and damage our capacity to defend ourselves and so it goes.

The more desperate they get the more stupid the scare statements become. Inflation become hyperinflation; debt become crippling, government provision of infrastructure becomes rampant socialism and coervice fascism – with the proponents of these ideas not realising that socialism and fascism cannot really co-exist in the way that educated individuals would use those terms.

But never mind the details like that – only left-wing academics (meaning all academics minus those who support free market ideas) would try to divert our attentions from the impending totalitariansim that the budget deficits foreshadow.

And never mind history either. If we don’t like it that history fails to support any of our ideas the answer is simple. We revise history leaving our the uncomfortable bits and embellishing other bits to the point that the real evidential basis is distorted or ignored.

The FT article suggests a “few possible reasons why repeated rounds of central bank communication and quantitative easing … have not brought about a strong recovery”.

First, “something structural has changed to hold back growth … perhaps related to savings behaviour or the changed distribution of income between labour and capital”.

Yes, the period in which real wages growth can be suppressed well below productivity growth so that the profit share rises and gives the financial markets increased access to real GDP at the expense of the workers will have to be over. The redistribution of national income towards profits which has characterised the neo-liberal years meant that consumption growth had to come from credit (debt accumulation) rather than real wages growth, which had long been the way that aggregate demand grew.

In turn, this meant that for economic growth to continue, the private domestic sector had to be coaxed (coerced, tricked – use whatever term you like to explain the way the financial engineers operates) – to accept ever-increasing volumes of credit. That strategy, in turn, allowed governments to boast smaller deficits or burgeoning surpluses.

All of which was clearly unsustainable and it was only a matter of time before the crisis emerged. It is clear that private borrowers are now unwilling to continue in that vein and that explains why credit growth is weak and the private contribution to aggregate demand growth is weak.

What it also means – a point that is totally ignored by the FT article and most other commentators who struggle to connect the dots – is that on-going budget deficits – the norm before the credit binge period – will also be required to provide the necessary aggregate demand to fill the gap left by the leakages from private saving.

Growth is weak or negative around the world because governments think they can engage in fiscal austerity at a time when the private sector is moving back to more conservative spending patterns. There is not “monetary policy” mystery. Monetary policy is a poor instrument for manipulating aggregate demand, especially when there is little appetite for private borrowing.

Second, the FT say that the central bankers think that they have not been aggressive enough given the “new headwinds” that economies are facing. The problem is that monetary policy tools will not significantly stimulate aggregate spending in the current environment as noted above.

A lack of spending is the problem. Monetary policy can only indirectly influence spending at the best of times and even then the direction of influence is open to debate given the complex distributional impacts of interest rate changes (for example, creditors lose, debtors gain, fixed income recipients lose when rates fall).

Third, the FT article says that it is possible that “quantitative easing … simply does not work”, which is more to the point. Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

The next several hundred words consider the usual myths of liquidity traps, negative interest rates, reducing interest paid on excess reserves, nominal GDP targetting to replace inflation targetting – and all the rest of these dead-end conversations that avoid a focus on the obvious – that the true problem is a lack of fiscal policy enterprise by governments and a reliance on monetary policy that is ill-equipped to provide the solution.

In relation to the ECB’s latest announcement – its Outright Monetary Transactions program – the FT article claims that it is:

… extremely controversial, with the Bundesbank, Germany’s ultraconservative central bank, viewing them “as being tantamount to financing governments by printing banknotes”. In addition, it sees the danger that if things go wrong, the potentially unlimited bond purchases “may ultimately redistribute considerable risks among various countries’ taxpayers” in the eurozone.

In the last several days since the ECB made the announcement I have read or heard on radio and TV many commentators, who should know better claiming that the central bank is just “printing money” to fund government spending. The same thing is said about quantitative easing.

Anyone who understands what these policies actually do will know that such statements – designed to elicit fear among the community – particularly in Germany – are fundamentally incorrect. They exhibit such an advanced ignorance that I suggest the governments expand their deficits initially by pushing more resources into primary and secondary education.

A moment’s reflection on the data confirms that there is no “printing” going on.

You can get regular updated data on the European monetary system from the ECB Monthly Bulletins.

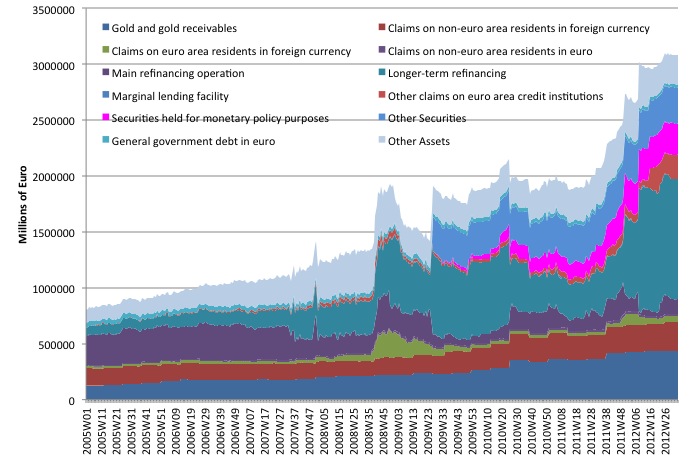

The following graph is shows the asset side of the ECB’s Balance Sheet (data is available HERE) from Week 1 2007 to Week 35 2012 (the latest available). The broad balance sheet headings and sub-components are:

- Gold and gold receivables

- Claims on non-euro area residents in foreign currency

- Claims on euro area residents in foreign currency

- Claims on non-euro area residents in euro

- Lending to euro area credit institutions in euro

- Main refinancing operations

- Longer-term refinancing operations

- Fine-tuning reverse operations

- Structural reverse operations

- Marginal lending facility

- Credits related to margin calls

- Other claims on euro area credit institutions in euro

- Securities of euro area residents in euro

- Securities held for monetary policy purposes

- Other securities

- General government debt in euro

- Other assets

Some of the categories have been ignored because they are miniscule in relative terms (check above list with legend in the following graph if you want to clarify which items are not graphed).

It is obvious that there has been a significant expansion in the ECB’s balance sheet. Unlike the expansion of the US Federal Reserve Bank’s balance sheet which has been driven mostly by its purchases of risk-free US government bonds, the ECB has instead mostly expanded the asset side of its balance sheet in two ways – both of which has involved the creation of riskier assets.

First, the now terminated Securities Markets Program (SMP) (the indigo area), which has been active since May 2010 involved the ECB purchasing government bonds of nations in the secondary markets that the private bond traders were pricing as risky. The relatively small volume of purchases had the effect of anchoring yields in the member states under atack from the bond markets although the size of the ECB commitment was not sufficient to prevent the yields rising again in subsequent primary market bond tenders.

Second, and much more significant has been the Longer-term refinancing operations (LTRO) (the jade area) which have accelerated substantially since the middle of 2011. These operations involved the ECB lending at near zero interest rates (3-year loans at 1 per cent) to the private banks which were struggling to access alternative sources of finance. The aim was to ease the credit restrictions in the economies in question.

The evidence is that the LTRO loans are mostly going to the Spanish and Italian banks while the sterilising operations (offering 0.25 per cent interest-bearing deposits) are mainly being taken up by the German and Dutch banks (Source: Gros, D. (2012) The big easing, CEPS commentary, CEPS, Brussels)

Some commentators have argued that the SMP and the LTRO have exposed the ECB to increasing and dangerous credit risk. However, the notion of “risk” in relation to the ECB is a misnomer given that it cannot go broke. Please read my blog – The ECB cannot go broke – get over it – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that like the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan (for two decades), the ECB has expanded its balance sheet substantially as it attempts to manage monetary policy in the crisis.

Now consider the following graphs relating to the “printing of money”.

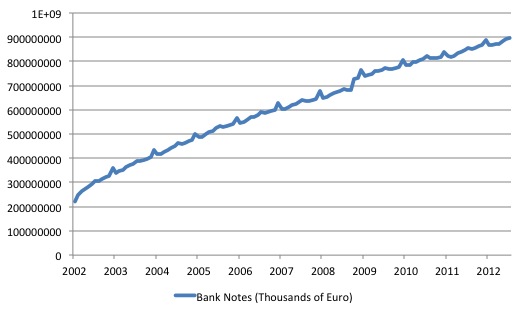

The first graph shows the quantity of Euro banknotes issued by the ECB (in thousands of Euros) since January 2002. The data is available from the ECB Statistical Warehouse. The grey shaded area is from May 2010 the date from which the SMP began and later the LTRO.

The regular spikes in issuance coincide with December (Xmas) – the larger of the two spikes and July (Summer holidays) which makes sense and is independent of the monetary policy initiatives that have driven the expansion of the ECB’s balance sheet.

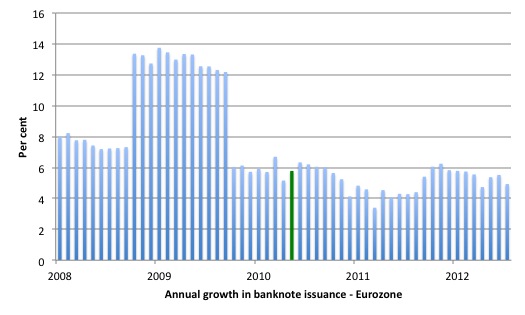

The next graph shows the annual growth in banknotes issued by the ECB since January 2008. The green bar is May 2010. Compare this graph which the balance sheet graph above to verify that the growth in banknotes has been orthogonal to the balance sheet events.

So there is some printing going on – regular and predictable – and dictated by the preferences of banking customers and the banks for vault cash. The balance sheet expansion of the ECB (and the US Federal Reserve) is not correctly or accurately described as printing money. Quantitative easing is not printing money.

As I explain in this blog – Quantitative easing 101 – quantititave easing (or credit easing in the ECB) are just asset swaps. The central bank just swaps a reserve balance for a government bond. They get an asset and give an asset.

Even central bankers themselves confuse the public on this point.

Remember the interview that Ben Bernanke gave Scott Pelley from the US program 60 Minutes. The interview was largely a litany of mainstream statements but at one point the Chairman gives the game away to the interviewer Scott Pelley. Apart from Bernanke’s very clear statement about how governments actually spend, the interview reveals the confusion that the top banker has with the way the modern monetary economy operates.

If you listen to the interview (the link will take you to the video and the transcript) you will realise that at around the 8 minute mark Bernanke starts talking about how the Fed (the US central bank) conducts its “operations”.

Interviewer Pelley asks Bernanke:

Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?

Bernanke replied, reflecting a good understanding of what we call central bank operations (the way the Fed interacts with the member banks):

It’s not tax money. The banks have accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank, we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed.

He then said:

It’s much more akin to printing money than it is to borrowing.

The interview then asked:

You’ve been printing money?

To which Bernanke replied:

Well, effectively. And we need to do that, because our economy is very weak and inflation is very low. When the economy begins to recover, that will be the time that we need to unwind those programs, raise interest rates, reduce the money supply, and make sure that we have a recovery that does not involve inflation.

So after getting the point correct that there is no financial constraint on Federal government spending (in this central bank transactions) which comprise the central bank making electronic entries into accounts in the commercial banks things start to run of the rails.

He then completely confuses the public by claiming that this is printing money. The central bank is always printing money (notes and coins) to meet our circulation requirements but this has nothing to do with it monetary operations. It is no wonder that the public is confused.

Please read my blog – Bernanke on financial constraints – for more discussion on this point.

The FT article seemingly realises it has run out of space and hasn’t mentioned hyperinflation. Redressing that obvious scripting error it says that central banks might “become more radical still” by buying bonds that would involve the introduction of “credit risk on to their balance sheet”. Of-course, they conclude that:

While none of this is palatable, it is better than the really radical ideas that may gain traction if economic malaise lingers, such as the infamous “helicopter drop” … A variant of this proposal is to finance the spending of government temporarily, allowing it to cut taxes for a period. This monetary financing of government is outlawed in Europe for the good reason that when it has previously been tried direct money-printing has ended in hyperinflation. An economy cannot provide sufficient goods and services to match all the newly minted cash at prevailing prices, and inflation takes hold.

Central banks have regularly bought treasury bonds to cover deficits. Hyperinflation has not been the result. It is a lie to suggest otherwise. Hyperinflations have been very special events which special circumstances. Those circumstances are not remotely to be seen in Europe at present.

As long as the government spending growth matched the growth in real productive capacity there would be no serious inflation emerging from the demand side.

The FT article concludes that:

The textbook is not providing the answers. When that happens more radical options come to the surface.

It depends on which which book you are reading. The mainstream macroeconomics textbooks have never accurately depicted how the fiat monetary system worked. Rather they provided a litany of theory aimed at advancing a particular ideological viewpoint which claimed that self-regulating private markets delivered optimum results and maximised wealth for all and that most government activity is damaging.

Conclusion

The ECB plan will fail because it fails to address the problem. Growth is needed desperately in Europe. Nations cannot reasonably maintain unemployment rates above 20 per cent indefinitely. Youth unemployment rates above 50 per cent are a time-bomb which will undermine future prosperity and risk major social unrest.

Forcing nations into austerity packages which ensures they remain in Depression indefinitely will not solve the problem.

The ECB would have been better accompany their announcement of unlimited bond purchases with a plan to ensure growth is fostered where it is needed most.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What frustrating is that the conditionality means that the central bank will struggle to rely on expectations to set the interest rate of bonds. Yet if they had announced a threat of unlimited and unrestricted interventions the market would have moved to the announced target rates likely without a Euro being fired.

The gambling now will move to deciding whether the Eurozone countries under threat will sign up to have their countries turned into Greece.

one question about the inflation risk of fiscal stimulus

often mmt characterizes the net spend as providing the private sector with

the ability to meet it’s saving desires

yet many people and firms have negative savings

whilst very few have enormous savings

if we presume given the chance that the many would emulate the few

large fiscal stimulus would mean a large increase in non inflationary savings

as well as increasing productive capacity by stimulating demand

we could conclude savings represent future purchases and store up inflationary pressures

but I am not sure if the evidence is there for that

rich men like to let their offspring to inherit wealth

a part of which the state destroys in taxation

At least the ECB didn’t name the programme “Market Monetary Transactions”. That would have been confusing.

Hi Bill,

“…draining reserves expand lending…” did you mean contracts ?

I got a kick out of this little thing at Spiegel Online: http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/spiegel-commentary-on-ecb-bond-purchase-program-a-854851.html – he’s basically complaining about how someone unelected (Draghi) can just decide to buy European public debt even though the German government is opposed.

Suddenly an awfully inconvenient thing, an independent central bank.

Kevin Harding:

I’ve asked the same question before in somewhat different way. A concrete example: Japan’s debt is 200% of GDP (or higher by now). That is net financial assets of the private sector (saving for retirement?). If at some point … Japan’s baby boom retires, they want to spend that money it could presumably be in excess of productive capacity. In fact, it seems likely given Japan’s demographics. Could that lead to high inflation? Of course the problem for them is actually a ‘real’ one. Too few workers to retirees. Maybe technology will save the day … I think that is why Japan has invested a lot in robot technology.

Can we claim Europe is in to a governament debt and loan to the private sector traps ?

Spain Italy Portugal and Greece non performing loans increased so the private debt exposure is huge.

Accordingly to Monstericht Treaty deficit can’t exceed 3%.

Loan to the private sector -2% and M3 increasing. http://www.zerohedge.com/sites/default/files/images/user5/imageroot/2013/07/M3%20Update%20June.gif

Governaments with debt/GDP above 100%. Debt increasing GDP decresing and the relation is non-linear.

Thanks too much Professor Bill.