I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Japan – up against the neo-liberal machine

I have been intrigued with Japan for many years. It probably started with the post-war hostility towards them by the soldiers who saw the worst of them. The Anzac tradition was very unkind to Japan and its modern generations. It always puzzled me how we could hate them so much yet rely on them for our Post-World War II boom. I also thought we owed them something for being part of the political axis that dropped the first and only nuclear weapon on defenceless citizens when the war was over anyway. Whatever, I have long studied the nation and its economy. So yesterday’s election outcome certainly exercises the mind. Will it be a paradigm shift or a frustrating period where an ostensibly social democratic government runs up against the neo-liberal machine? I put these thoughts together about while travelling to and from Sydney on the train today.

Japan is already very important. While the government didn’t set out to provide us with an excellent living exhibit of how a modern monetary economy works when there are on-going public deficits of significant sizes and a huge growth in public debt the fact of the matter is that circumstances came together as a result of their miserable 1990s to deliver that outcome.

We learned that interest rates do not sky-rocket and inflation does not accelerate when deficits and debt issuance are on-going and huge – quite the opposite. Modern monetary theory was able to explain these outcomes because it has a thorough understanding of the operational nature of the financial system. However, the dominant mainstream macroeconomics failed dramatically to comprehend what was happening.

I have written about this in the past – several notable economists prognosticated on what Japan should do to get out of their malaise in the 1990s but none of them understood the problem or the options available to the sovereign government. They all gave poor advice. The way Japan recovered after that decade of poor economic outcomes was through fiscal policy. Monetary policy had little to do with it. The Japanese experience demonstrates the poverty of mainstream theory.

The same economists are at work again now offering spurious advice to all and sundry ably supported by the media economists, who rely heavily for copy on the material the bank economists and the conservative think-tanks pump out. Our memories are short and we allow these so-called experts to prognosticate when in fact they have revealed their lack of understanding of the operations of a modern monetary economy over and over again. More the fools us.

Anyway, given my interest in Japan I thought it would be good to write about the monumental event that we witnessed yesterday. I think it provides a good example of how paradigm change may be in the wind but will quickly blow away.

The election saw the Democratic Justice Party of Japan (DJP) toss the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) party from government. Since its formation in 1955, the conservative LDP has held power in Japan continuously apart from a brief 10 month interregnum in 1993-94.

While some of the voter discontent reflects political factors – for example, 3 Prime Ministers since 2006 – the current downturn is the worst recession in the Post-World War II recovery period. The sheer gravity of the current economic malaise would have been enough I think. While the 1991 downturn was severe and the so-called “lost decade” saw changes to Japan’s lifetime employment system which damaged the security of the workforce, the current recession dwarfs that earlier episode.

But things don’t happen overnight in Japan and it is the accumulation of events since the 1991 downturn that undermined the faith in the conservatives and finally saw them ousted. A commentator in the Sydney Morning Herald today said that the electoral rout:

… is not a story about how the LDP, with an unpopular prime minister and facing economic problems, lost an election … This is about the end of the postwar political system in Japan.

An important point is that the landslide election result may give the new government the super-majority (> 2/3 of the seats in the lower house legislature). This means that the power of veto held by the upper house would be denied. But in the 2007 election a pot-pourri of non-conservative parties (including the DJP) took control of the upper house anyway, which was really signalling the death knell of conservative rule.

Whichever way it goes the progressive agenda that the Democratic Justice Party of Japan (DJP) plans to pursue will not be impeded by conservative forces that have ruled Japan as a result of the balance in the legislature.

What will be important though is the way in which the conservative forces regroup in the media and elsewhere to maintain the neo-liberal pressure that is already evident in statements made by the incoming Prime Minister. More about which later.

The decline

It is clear to me that the neo-liberal period in Japan has devastated the security of the middle class which accounted for more than 80 per cent of the population. A person could rely on retaining full-time employment on good wages for life as long as they completed secondary school. The 1991 recession which followed the real estate collapse and poor investments by the financial sector led to the “lost decade”. The Japanese government under the neo-liberal helm of Prime Minister Koizumi started deregulating things that had previously been integral to providing this security.

Around 30 per cent of Japanese workers are employed in low-paid, casual jobs that offer no security. While Japan enjoyed stable growth this was not a problem. But the numbers of temporary workers has risen as the revered life-time employment system that generate prosperity in the Post-World War II period for the vast majority of workers has been steadily dismantled under neo-liberal urging.

In the current recession, the flux and uncertainty of capitalism has impacted most severely on this cohort many of whom face homelessness as well as unemployment. And the Japanese government has been found wanting in dealing with the fall-out.

So since the major recession of 1991, Japan has been steadily undermining its Post-World War II recovery miracle, which was ably assisted by the very generous Marshall Plan (a demonstration of the powers of fiscal policy and international aid).

You can summarise the decline of the conservative Japan rule in one word – No-jyuku sha – which we take to mean homeless but the literal English translation is “campers in the rough”. The No-jyuku sha are rising and spilling out all across the major Japanese cities in places where the power elites definitely do not want to see them.

When I was last in Japan I was staying at a well-appointed hotel courtesy of the Japanese Government and situated close to the main administrative and central banking area. A lot of well-heeled characters would traverse the streets in this district every day. Well I went for my usual run (which I do when I haven’t a bike available) in the park nearby and I got a major shock – gone was the beautiful quiet park and in its place was a burgeoning housing estate.

Well that is probably too generous. It was a tent and cardboard city providing shelter for the increasing numbers of homeless people that had been displaced by the breakdown of the lifetime employment system. All this in the main government district of the second largest economy in the world.

I did some casual research each morning I was out running by asking the locals a question or two about the tent city. I learned that welfare services including food delivery were provided to the homeless by trade unions and welfare groups each day. You see big queues in the morning lining up near the impromptu kitchens that the welfare agencies (including the unions) set up in the parks to provide a minimum of sustenance to unemployed workers, who once they lose their jobs often become impoverished soon after.

I learned that middle-aged men who lost their jobs typically would pretend to their families that they were still employed and leave home each day as if nothing was wrong. Once they ran out of money they would be so ashamed they would either commit suicide (rates are high in Japan among men) or disappear and turn up in the tent cities.

The dominant sentiment towards the No-jyuku sha has been that they create an urban nuisances and their scratched together dwellings represent urban blight. Local city authorities continually try to evict the residents using so-called “environmental beautification programmes”.

But the other side of this coin is that these “cities” have become points of mobilisation by unions, welfare agencies and the like who attempt to kindle solidarity. Part of that movement is responsible for the demise of the conservative government.

More tent cities have propagated during this recession as the mass layoffs have left workers without income and, inevitably, in a society without adequate social safety nets, without a home.

Earlier this year, during the traditional New Year’s celebrations, a major inner city park (Hibiya Park) which is located in the inner city near the Imperial Palace, the Diet building and the Tokyo’s business district became a tent city. The proximity of the “city” to the main areas of government and commerce was considered too confrontational to Japan’s sense of decorum and it was quickly closed. But the scale of the problem did force the city authorities to think laterally and actually provide new forms of accommodation for the unemployed temporary workers elsewhere in the city. This was a sign that things were turning.

Some data to tell the story

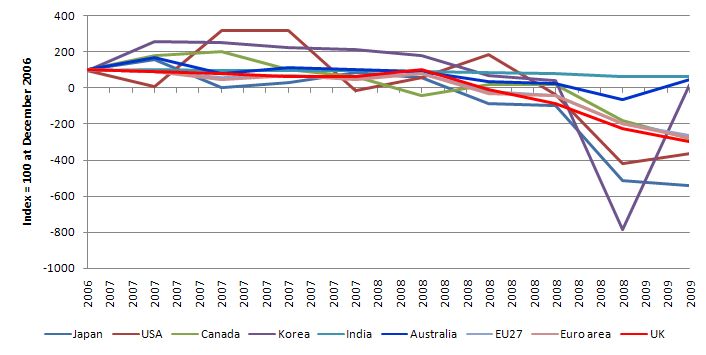

To get a feel for what has happened in Japan during this recession I assembled the following graphs. The first graph shows the GDP growth rates for selected countries indexed to 100 at December 2006 to provide a basis for comparison. The extraordinary V-shaped pattern of South Korea stands out. The other point to note is that so far, India and Australia have resisted the worst of global recession in output growth terms.

However, it is clear that Japan is now the worst performing country followed by the US although Canada, Europe, and the UK were still in sharp decline during the March 2009 quarter. In the March quarter, the index number for Japan was -543 compared to 100 in December 2006. That is a massive decline in income generation.

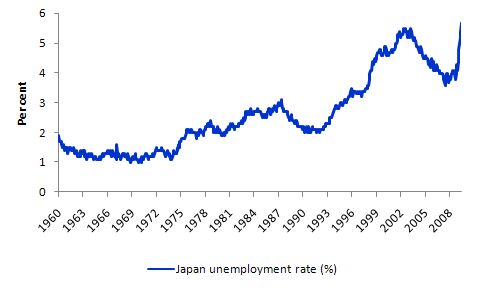

This decline shows up in the labour market as spiralling unemployment. The next graph shows the evolution of the unemployment rate in Japan since 1960. You can see the way in which Japan has slid as the successive conservative responses to changing circumstances have played out.

They largely avoided the rapid rise in unemployment rates that accompanied the OPEC oil price hikes in the mid-1970s. The neo-liberal breakdown of the life-time employment system hadn’t begun at that point and fiscal policy combined with the solidarity culture kept the rise in unemployment to a minimum.

However, as the neo-liberal agenda gained traction the rot set in the step-jumps in unemployment since have undermined the sense of well-being throughout Japan.

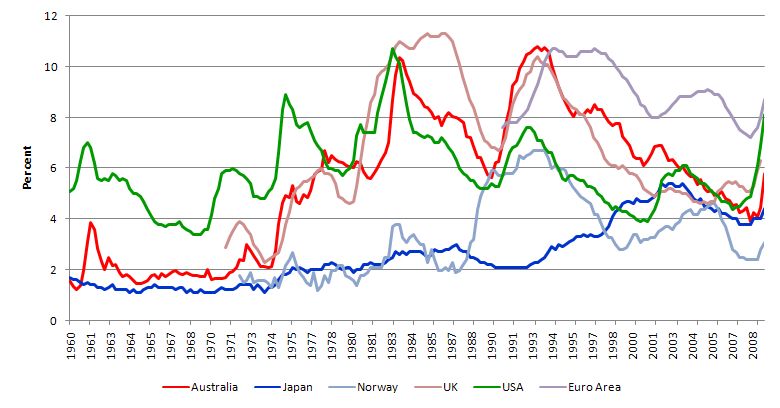

It is sobering to put the Japanese experience into perspective, however. The next graph compares the evolution of the Japanese unemployment rate (in quarterly seasonally adjusted terms) since March 1960 against Australia (March 1960 onwards), Norway (March 1972 onwards), the United Kingdom (March 1971 onwards), the USA (March 1960 onwards) and the Euro Area (September 1990 onwards).

I have data for constituent countries in the Euro zone (such as France, Germany, and Italy) back to March 1960 but it complicates the graph too much. The history of these countries is not dissimilar to the Japan until the 1982 recession and from then onwards resembles the Euro zone performance, which is to say the least, dismal.

You can see that despite the rising unemployment rate in Japan over the neo-liberal period, which has culminated in the change of government yesterday, the economy still performs a lot better than the English-speaking economies including Australia.

One of the reasons for this is that despite their highly productive manufacturing sector, which is blueprinted by plants around the world, their service sector is deliberately inefficient, when measured in narrow neo-classical terms. The service sector is intentionally labour intensive to ensure that as many jobs are created as possible. The first few times you visit Japan you cannot help but notice how many shop staff there are ready to help.

The division of labour is a bit unclear to the visitor but as you learn more about the economy you realise there is a plan to this – to maximise employment. It is a clever strategy – maximise narrow efficiency in the traded-goods sector and maximise employment in the non-traded, non-competitive sector of the economy. And this plan even evaded the neo-liberal drive to impose narrow productivity notions on the entire economy – at least it mostly evaded it.

That is why the unemployment rate overall has not risen as much as it has in other countries which have allowed their service sectors to be the arenas of increasing casualisation and disadvantage.

However, this is not to say that the changes over the last 18 or so years in Japan haven’t been devastating and created an increasing class of low-paid and insecure workers. They clearly have and the previous government finally paid the cost of allowing (and promoting) this strategy to unfold.

The way ahead

Martin Fackler in the New York Times today described the change of government in these terms:

Many Japanese saw the vote as a final blow to Japan’s postwar order, which has been slowly unraveling since the economy collapsed in the early 1990s. It was also a crushing setback for the Liberal Democratic Party, a Cold War-era creation that led Japan from bombed-out rubble to economic miracle, and kept it firmly in Washington’s camp, but that has appeared increasingly exhausted and directionless.

The change likely is fundamental. The Post-War World II growth strategy has been to focus public spending on corporations via national infrastructure projects. The DPJ say they will change this and stimulate domestic consumption by putting more income into the hands of consumers and welfare groups. Japan has very high household saving rates significantly driven by the lack of a national superannuation scheme.

The new government intends to change that and introduce a meaningful social safety net to divert funds to the poor. They will reform the is dysfunctional social security system and increase pensions for households in poverty.

These initiatives will have the immediate effect of stimulating domestic demand and increasing employment. So the progressive agenda includes addressing the increasing insecurity of employment and stimulating wages growth now at record lows. It also means addressing the highest unemployment rates since Labour Force data was first published in 1960. Official unemployment is now at 5.7 per cent.

They have promised free secondary education, free medical care for expectant mothers, and generous child support allowances, all aimed at addressing the declining population.

There are also hopeful signs in terms of climate change action.

However, while the family-oriented strategies are intended to reverse the population decline, the motivation has been driven by the mythical intergenerational scare campaign that the neo-liberals are running as a major plank in their campaign to diminish the size of governments around the world. More about which later.

One of the most significant changes will be the challenge to the so-called “iron triangle” – a nexus of conservative politicians, the bureaucrats and big corporations – which has allowed the bureaucrats to dominate the economic agenda over the democratically-elected politicians.

In part, this shift in power will play out in the planned shift in national government policy focus away from provision of national infrastructure towards consumers.

The dominant power of the bureaucracy has meant that the Japanese government approach to fiscal policy has been concentrated on the provision of large national infrastructure projects which have benefited large corporations but done little to improve job and income security for the low-paid and/or impoverished pensioners.

The new government has signalled it will reorient its policy focus to place an emphasis on domestic consumption and improving social welfare and push national infrastructure provision to the private sector.

On the face of it, this will increase the living standards and prospects of the poor who have increasingly borne the brunt of the poorly performing Japanese economy.

But it also spells the key dangers that the new government faces – which all governments around the world are now going to have to address.

The neo-liberals didn’t lose the election!

While it is likely that living standards will rise for the poor and downtrodden in the post-industrial Japanese society, I foresee new issues arising from their misunderstanding of how their currency works.

The new government has already voiced concerns about the need to cut the budget deficit and hence they think they have to use more private initiative in the construction of their large public infrastructure projects, which have previously been the domain of public investment.

The debt-deficit hysteria is peaking in Japan at present. The claims that the public debt will cripple the nation and the future generations are being voiced by conservatives everywhere. Even though the Japanese population came to dislike the conservative government they are still very conservative overall with respect to their views on public debt.

The Guardian Newspaper said overnight that:

Much uncertainty centres on the DPJ’s spending commitments as Japan, already saddled with a huge public debt, emerges from its deepest recession since the war. Richard Jerram, the chief economist at Macquarie Securities in Tokyo, described Hatoyama’s 16.8tn yen investment programme, as a “quasi-socialist approach” that would harm Japan’s public finances and blunt its competitiveness. “The core of the DPJ’s economic policy seems to be a fantasy Robin Hood scheme, aimed at appealing to as many voters as possible,” he said.

Conservative News Limited hack Greg Sheridan notes this morning in The Australian that the DJPs “economic populism is dangerous” because it “opposes the market-based reforms that Japan’s economic system … still needs.”

I could produce many more quotes from commentators overnight all rehearsing the same line.

The neo-liberals are running rampant now and predicting a maelstrom. This dominance of neo-liberal thinking will be a major constraint on the new government and it is already showing a compliance to the views.

The family-first policy proposals are a sop to the intergenerational debate.

The decision to shift spending priority to welfare away from national infrastructure provision is an example. The new Prime Minister has already said he will raise taxes to “pay for” the new spending initiatives. He has also promised to cut spending on major infrastructure.

The private investment jackals who have been indulging in wasteful, inefficient yet highly profitable private equity projects in the West are poised to capitalise on this shift in Japanese sentiment. They see Yen-signs before their eyes and are on the move already.

One commentator in today’s Australian says Australia investors are “primed and ready, as Japan rebounds from the global downturn with more resilience and speed than expected …”

The upshot according to the Australian commentary (consistent for a News Limited journalist) is that there will be:

… a focus on public-private partnership projects – a new concept for Japan. They are now essential as government debt soars past double the country’s annual economic output, with public infrastructure spending totalling $7.5 trillion since 1991. And the latest central government stimulus package crowded out bond-raising opportunities for regional governments.

Infrastructure is emerging as a new “asset-class” in Japanese financial markets. We never learn!

If they really understood the fiat monetary system they could continue to provide public infrastructure and extend better safety net protection for the poor. The large deficits that the Japanese government runs is symptomatic of the huge saving desire of the domestic population. Not even the traditionally strong net export performance can offset the high saving ratio.

The saving ratio will also decline as more safety net provisions are extended to the population, who at present feel as though they have to provide for their own retirements. The introduction of a national superannuation scheme would also help.

In that sense, the deficit would fall anyway as consumption increased.

Impact on Australia

What happens to Japan is of importance to Australia in terms of our narrow economic interests. In all this talk about how dependent we are on China, the fact remains that Japan is still our largest trading partner.

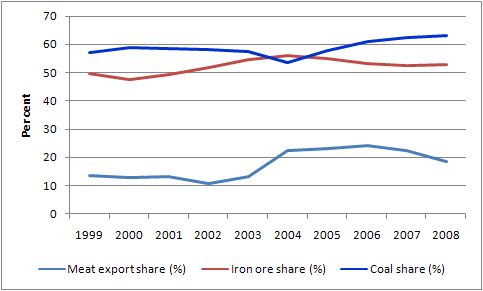

In terms of our exports we are Japan’s second highest source of meat imports (behind the US) and its most significant coal and iron ore source. The following graph shows our percentage contribution of Japan’s total imports in these three commodities since 1998.

Japan remains our largest buyer of exports. While the graph shows our resource contribution to the Japanese trade, we have also increased our exports of services to Japan in recent years. Japan is also a significant investor in Australia – rising 16 per cent in the last year.

Final reflection …

Japan is important because apart from everything else it is going to show us how a social democratic government which has inherited a neo-liberal mess struggles to gain credibility in a world where the dominant ideology is still fighting tooth and nail to retain its influence.

There was an interesting article written by Jacob Saulwick in today’s Sydney Morning Herald – And so the crisis ends – not with a bang but a whimper, where asks:

Where is all the outrage? In the coming month we hit the one-year anniversary of the most frenetic weeks of the financial crisis, fast days when it seemed like some sniper from above was picking off the big names of banking – Lehman Brothers, AIG, Merrill Lynch – and governments were scrambling to salve the wounds of the system with big swabs of public money. Even then, amid the fear, there seemed a sense that this crisis represented an opportunity to make the world a better place. Whether motivated by schadenfreude or optimism, there was a feeling – in respectable circles and out – that the comeuppance of the bankers was kind of a good thing. That greed had got out of hand, and now there was a chance to start again and draw up a fairer, more stable, more just kind of capitalism. A year on, and it looks like the financial crisis is passing and little will have really changed. Banks have gone back to making money. Unemployment is higher but not dramatically so. And apart from new school buildings and some extra home insulation, there is a good chance that the next decade in Australia will look a lot like the previous one.

This resonates with a theme that I have been developing in my work. While at first blush the events of late 2007 and 2008 (GFC) offered the prospect for a paradigm change in economic policy of the same dimension that occurred in 1975, the reality is setting in that there will be no significant paradigm change this time around.

This has undoubtedly been the largest economic crisis since the 1930s Great Depression and required all the tools that the neo-liberals hate to stop the world economy from slipping as far as it did in those days.

Still, with no shortage of irony, the conservatives can still raise their heads in public and lecture us on the benefits of the free market and the futility and evil of government intervention. Intervention that is, which benefits the broader population rather than the corporate welfare that the top-end-of-town have become used to receiving and to which they would claim is their right.

The irony of this is as stunning as the shamelessness of their position. How is it that we are so stupid that we cannot see the brazenness of it all.

The monetary and fiscal bailouts have been huge and pushed massive amounts of public funds to the class which created the problem in the first place.

Jacob Saulwick notes that:

Adjusted for inflation, the cost of the US banking bail-out … is more than what was spent on the Marshall Plan, the Louisiana Purchase, the moon race, the savings and loan crisis, the Korean War, the New Deal, the invasion of Iraq, NASA, and the Vietnam War put together. That has to have some impact. When the panic is on, governments do what they can to patch things up. It is not necessarily a good time to force change … [but] … The result, after the heaviest government intervention in history, is that the crisis is easing. But that is a long way from the talk of a new world order that was floating around only a year ago.

In other words, the progressive side of the debate has not been able to mobilise enough resources to maintain the edge in the debate. The forces against this agenda are well organised and well funded by the corporate sector. If the progressive agenda is to gain traction fundamental changes have to be made in the way alternative dialogues are developed and presented.

A good place to start would be for the progressives to embrace modern monetary theory and abandon gold standard thinking. For years there has been major resistance by some progressive circles to move beyond the mainstream macroeconomic textbook conceptions. I have failed to understand that reluctance.

Unless you jettison the government budget constraint mentality that is at the heart of neo-liberal theory (and based on the false analogy between a household and the sovereign government) you will always have the dilemma that the new government in Japan is now contending with. That is, being forced to restrict spending by the political process in the context of being able to identify glaring areas of neglect that need more public spending. The dilemma is that the extra spending would push the economy back towards full employment and the society back towards higher levels of equity but that the political process, dominated by conservative hacks, are militating against it.

You cannot achieve these goals if you are always constrained by neo-liberal conceptions of what is an appropriate fiscal position.

Unless the top end of town decides to reduce the divide between rich and poor nothing will usurp the neo-liberal ideology in the forseeable future. All the commonsense and quality analysis in the world (as presented by you here) will have little if any influence over the crap big business, government, and neo-liberal think tanks have been feeding the masses since who knows when.

People need to hear the truth about what is happening but they also need to hear it in terms that will encourage them to act or sanction those currently in power be it Big Business / Government / who ever.

As an example to show people the ills of logging in Indonesia you don’t show them graphs and charts. Instead you show them the bloodied carcass of what was once an Orangutan and it’s baby.

food for thought …..

Cheers, Alan

Problem is that almost nobody on the progressive side understands the options open to government today. As I’ve said before, while it may be completely wrong it is also extremely easy to understand that government must finance their spending just like a household and that taxes and bond issuence pay for the spending. From the point of veiw of the user of currency, that just makes such clear cut, perfectly logical sense.

When they first announced their deficit spending plans (which was really only just before I stumbled across billyblog) I remember everyone around me saying “where are they getting all this money from?” – and I was wondering the same thing.

At this point in time at least, the neo-liberal debt truck seems to have four flat tyres – people still believe that the government needed to borrow in order to finance the deficit but it appears that not many people are all that concerned so long as some measure of recovery appears to be underway. As the next election approaches of course, the oppostion will put new tyres on the debt truck and install a turbo charger and the b.s machine will be pushed to maximum overdrive – after all, ” the debt will eat your children and grandchildren!!!!” is all they really have to run with.

For my part, I keep trying to explain to people how it works and that there is no reason to fear government spending but it is mostly only on the blogs that you find people who are interested and willing to listen (or argue). Shame.

John and Jane Average couldn’t care less right now but as soon as the election is announced, I’ll be having my say everytime some I work with or meet in daily life says “you know, the coalition are right, this debt is a big worry”.

Good post Lefty.

When people find out that the purpose of taxes is too support / drive demand for the government / RBA’s otherwise worthless currency the poo will well and truly hit the fan.

Good post Lefty. Really nice.

Cheers Alan and Ramanan.

Unfortunately, one of the problems I see with people realising that taxes levvied by the federal government don’t actually pay for anything is that poor, struggling $500 000 + p/a households will demand to keep their middle/upper class welfare in the knowledge that their tax payments – the ones that their accountant hasn’t found ways to circumvent – really only serve to create demand for otherwise worthless tokens.

But we should just keep plugging away. One of the biggest penny-droppers I have found for people prepared to listen is to pull out a $note and ask them if absolutely everybody has to earn or borrow this stuff in order to get hold of it, and nobody at all can create it……….where is it coming from then? Who or what is the original source? They quickly realise the impossibility of the notion that there is nobody at all out there that does not have to acquire it from elsewhere first. Seems to be a start anyhow.

cheers

Dear Lefty,

“pull out a $note and ask them if absolutely everybody has to earn or borrow this stuff in order to get hold of it, and nobody at all can create it……….where is it coming from then? Who or what is the original source?”

I have also found this to be a very effective way of setting people straight. What they cannot grasp though is why the people with all the money are supposedly against government spending.

cheers

Dear Alan,

Very good point. However, some skeptics would still argue that this money has been created once and forever (ideally, for them) and any new creation will immediately corrode the value of that $note you showed them. Government spending operation through simultaneous reserve and deposit creation is just a technicality for them. Its not so trivial to get across the idea “… for an economy to keep growing and to remove unemployment and poverty, the government has to be in deficit forever“

Dear Ramanan

Unless the external sector is continually in surplus. Of-course, by definition this exception cannot apply generally (not all countries can be in trade surplus). Further, for one country it is unlikely to persist. For example, Norway will eventually run out of North Sea oil.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill,

Yes of course the flow identity is S – I = G + NX – T.

You may still point out that there are further complications but I guess since you have not emphasized these corrections anywhere, they are not that significant from a pedagogical perspective